Tagged Under:

Evolution of the Modern Piano: From Dulcimer to Disklavier

Thousands of years in the making … and still seeing improvements today.

Most historians agree that the piano was invented in the early 1700s by Bartolomeo Cristofori, but its lineage actually goes back much further than that — all the way to ancient times.

Let’s take a look at the long and fascinating evolution of the modern piano — one of the most popular musical instruments ever created and a mainstay of so many different kinds of music, from classical to jazz, pop and beyond.

Progenitors of the Modern Piano

The development of the modern piano can be traced to 2650 B.C., when a Chinese instrument called the ke was introduced. It had strings strung over a movable bridge on a wooden box that could be plucked to produce various tones.

In 582 B.C., Pythagóras began experimenting with musical sounds and mathematics, inventing the monochord. Some 400 years later, a movable bridge was added to the monochord allowing for increased intonation. By approximately 1000 A.D., clavis (keys) were applied to the monochord, used to prick strings on a scale division. (You can hear the meditative sound of a monochord in this video.)

Some time in the 14th century, a successor to the monochord — the clavicytherium — made its first appearance. This instrument was also played with a keyboard, but had its strings arranged in a harp-like triangle.

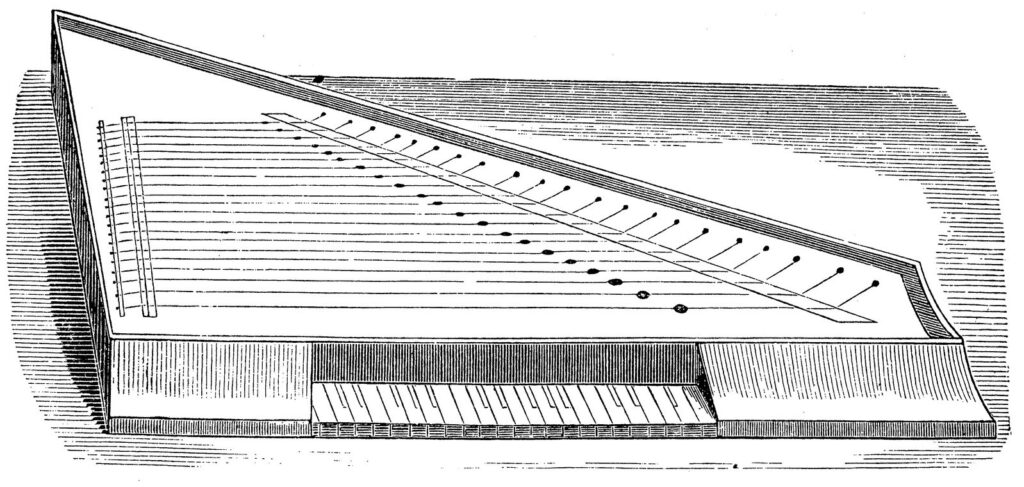

Although the piano is best classified as a string instrument due to the fact that the sounds come from the vibration of strings, it can also be classified as a percussion instrument because a hammer strikes those strings. In this way, it is similar to a hammered dulcimer, an instrument that originated in the Middle East around 900 and spread to Europe in the 11th century.

The hammered dulcimer is a type of zither that uses small mallets called hammers to strike wires stretched across a simple resonating box. It was widely used throughout Europe during the Middle Ages and can still be heard in some modern folk music today.

Because it was the first instrument to use strings, a soundboard and hammers to produce musical tones, the hammered dulcimer is considered by many to the direct ancestor to the piano. However, there were to be several intermediate stops along the way.

The Clavichord, Spinet and Harpsichord

One such instrument was the clavichord, which first appeared in the 14th century and became popular during the Renaissance Era. The clavichord used the same stringed components of the hammered dulcimer, but it incorporated a keyboard that triggered metal blades, called tangents, to strike the strings. It had more strings than the clavicytherium (for a range of four to five octaves) and had pins fastened to the keys; eventually, a cloth was placed between the strings that acted as a damper. Lap versions of the instrument were played on tabletops while others were built on stands varying from 3 1/2 to 5 feet in width. However, because clavichords were not loud enough for large performances, they were mostly used as practice instruments or for composition.

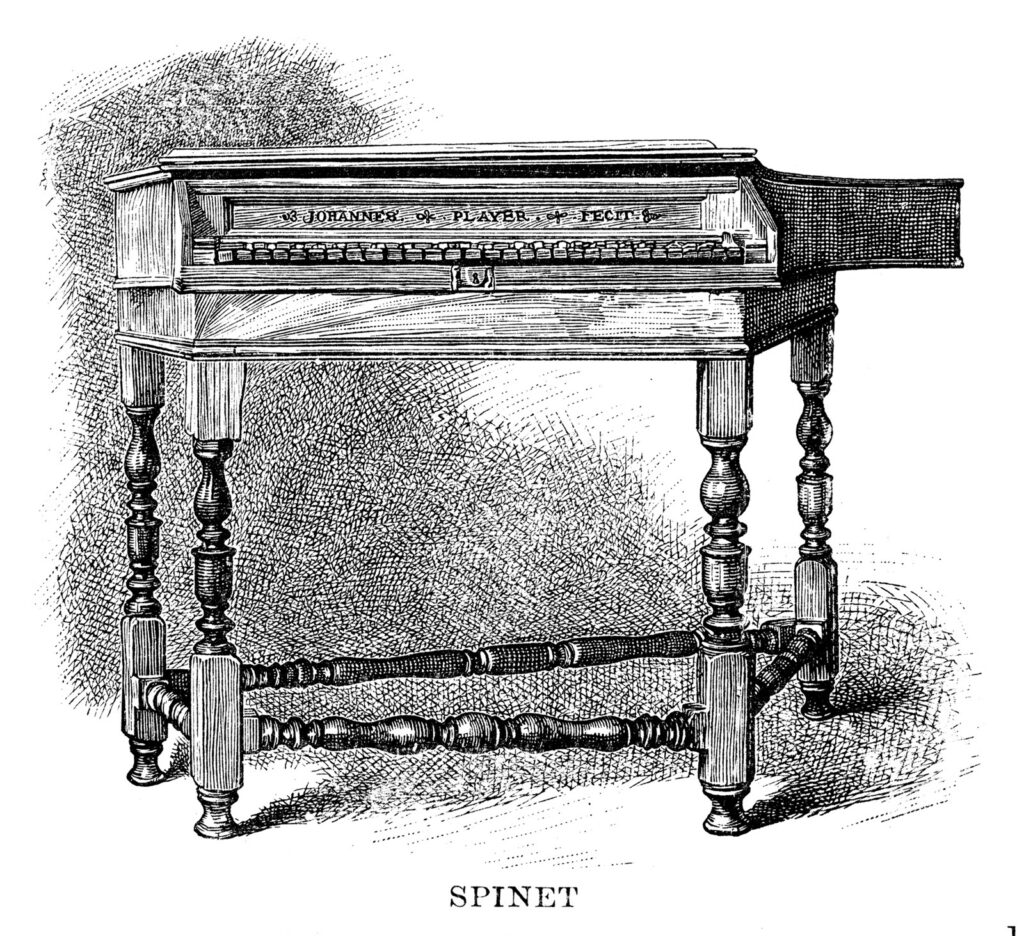

In the early 16th century, adaptations of the clavichord led to the introduction of a new instrument called the spinet, named after inventor Giovanni Spinnetti, though it was later called a “virginal” by musicians in England, often housed in an ornate cabinet. This was a longer-stringed clavichord with tangents that pricked the strings using a quill fastened to a jack. Unlike the clavichord, the spinet had no expression or way to manipulate the pressure or strength of the tone.

The limitations of the spinet resulted in numerous attempts at modification so as to obtain greater volume and depth of tone, with many European instrument makers introducing spinets in a case shape similar to that of a harp. This triangular harp-like appearance is essentially the shape of grand pianos today.

In 1521, a new keyboard instrument called the harpsichord was introduced as an offshoot of the spinet. When a harpsichord key is pressed, a quill plectrum attached to a long strip of wood called a jack plucks a string to make a sound. Its invention began as an experiment to improve the sound quality of the spinet, and its longer strings produced the desired volume, but the string plucking on the larger scale increased the intensity of the wiry and harsh tone.

Over the years, many attempts were made to improve the sound of the harpsichord, such as lengthening its case and the use of leather buffs and stops to soften the tone. By the end of the 16th century, harpsichords with dual keyboards were introduced, making it easier to play complex two-handed musical arrangements. Nonetheless, the instrument had serious limitations. Though the harpsichord is louder than the clavichord, its volume cannot be varied: The strings are plucked with uniform loudness no matter how hard or soft the player plays, and they are immediately damped when the key is released. However, its system of strings and soundboard, as well as its overall structure, resembles that of the piano, which is why many people view the harpsichord as the immediate progenitor of the modern piano.

Introduction of the Piano

Born out of the need to improve the sound quality of the harpsichord, the piano combined many ideas that had first been tried on the clavichord and harpsichord. Inventors began adding hammer actions to restore the smooth tone of the clavichord on the frame and case design of the harpsichord, but the individual generally recognized as the father of the piano was renowned harpsichord maker Bartolomeo Cristofori, whose gravicembalo col piano e forte, or “harpsichord that plays soft and loud,” was unveiled in 1711. Eventually, the name was shortened to fortepiano or pianoforte, and then, finally, piano.

The first pianos were actually very similar to a harpsichord, with one crucial difference. In a harpsichord the strings are set into motion by plucking (as in a guitar) and the loudness of the resultant sound is independent of how forcefully a key is depressed. In a piano, the strings are struck with a hammer and Cristofori invented a clever mechanism (called the piano “action”) through which the speed of the hammer and hence the volume of a tone is controlled by the force with which a key is pressed. This allows the player to vary the loudness of notes individually — something that was not possible with the harpsichord — and gave the piano new expressive capabilities that were soon exploited by composers such as Mozart and Beethoven.

Little is known about Cristofori’s life, but the few surviving examples of his work provide evidence that he refined the design of his piano over the years. Three of his instruments survive today and can be seen at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City (shown below), the Museum of Musical Instruments in Germany, and the Museum of Musical Instruments in Italy.

The first pianos were made by hand, and the music written for them was initially mostly confined to the aristocracy. However, the instrument became popular with the general public following the French Revolution in 1789, and demand increased. This led to the rapid industrialization of piano manufacturing. In addition, the music that had previously been enjoyed in the courts of aristocrats was now being performed in concert halls that were built to hold a thousand or more people. This, in turn, led to a desire for pianos with louder volume and longer sustain. The strings were strung under higher tension, and a sturdy iron frame began to be used to support them. The age had arrived when pianos could no longer be made completely by hand.

The Square Piano

In 1760, the square piano was introduced by Johannes Zumpe in London, England as a smaller alternative to the wing form design of the early grand pianos (see below). It was essentially a clavichord with metal strings, a hammer action and a reinforced frame.

In 1781, the position of the hammer action was changed to improve the resonance and make the sound louder (previously a downfall of the square shape). Further changes were mostly regarding the material from which frames were being made to achieve a better tone. The English makers were attempting all-iron and iron hybrid frames to allow for heavier strings and louder, more sonorous tone emanation, while German makers were devoted to traditional wooden frames, claiming the sound was too metallic and wiry when the strings were connected to an iron frame. Square pianos remained popular for the next 100 years before being supplanted by upright pianos.

The Upright Piano

Even as the square piano was rapidly rising in popularity, several unconventionally-minded inventors began experimenting with an upright piano. The first one is believed to have been made in Austria by Johann Schmidt in 1780 but the first upright with diagonal strings was introduced by British inventor Robert Wornum in 1832, and his design was to change the landscape forever. German manufacturers later improved on Wornum’s upright by building an iron frame with three strings for each note, which produced a robust sound and improved the overall tonal quality.

Since it took up less space than a grand piano, the upright piano — often elaborately decorated — quickly became popular. By 1860, nearly all square pianos in Europe were being replaced with uprights thanks to the increasingly industrialized city planning that mandated smaller, more compact pianos for urban spaces and in-home enjoyment. At around this time, American piano manufacturers began to shift their attention to developing uprights that could accommodate the square piano market. By 1880, the upright piano had completely replaced the square piano in America.

Torakusu Yamaha, founder of Nippon Gakki Co., Ltd. — later renamed Yamaha Corporation — started manufacturing upright pianos in 1900.

Upright pianos continue to be a popular choice for pianists with smaller budgets and tight spaces, making them perfect for schools, practice studios, homes, and public places like cafes and nightclubs. Models such as the Yamaha U Series (the most popular upright piano in the world), as well as the YUS Series (which incorporate many features from the company’s flagship CF Series grand pianos) and b Series are held in high regard by performers, teachers and students alike, and are found in many top music schools.

The Grand Piano

The early pianoforte designs utilized a “wing form,” similar to that of a harp laid down horizontally. By the late 1700s, manufacturers were beginning to understand the advantages of that design for superior sound quality, volume and engineering. The grand piano came to the forefront of piano making in 1776.

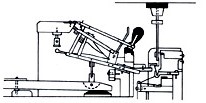

The natural horizontal plane utilized by the grand piano lent itself to the best action (the mechanism of the piano that causes hammers to strike the strings when a key is pressed) and string orientation for optimum playability, volume and tone. English inventor Robert Stodard’s action created for the first “Grand Pianoforte” in 1777 set the baseline for future grand pianos. Three years later, Viennese manufacturer Johann Andreas Stein and his daughter, Nanette Stein-Streicher, improved upon the original grand piano design to create a tone so desirable that Mozart, Beethoven and other composers wrote pieces specifically to be played on their instruments. This new action combined a forceful, direct strike with a slight wisp across the string that created an elegant tone that other makers could never achieve.

When pianists began competing with embellishments such as trills or fast arpeggios, or by repeating fast passages, there was an increased need for more responsive instruments. The revolutionary new action that answered that need and made it possible to repeat notes in rapid succession was invented in 1821 by Sébastien Erard of France. His double escapement repetition mechanism was a major development, and one that is in use, in a refined form, to this very day. The Erard mechanism allowed the pianist to quickly repeat a note without having to fully release the key. Up until its introduction, when a key was depressed, the hammer rose and struck the string but was not ready for the next keystroke, until it had fallen back to its at-rest position. Erard’s invention made it possible to prepare for the next keystroke even though the hammer had not completely fallen back.

In 1838, Erard added to his accomplishment with the invention of the capo tasto, which was a pressure bar that increased the rigidity of the strings, providing a counter-pressure to the hammer, thus improving the tone. This bar is now standard on nearly all grand pianos today.

By about the middle of the 19th century, the principles of the piano mechanism, and the devices that comprise it, had reached a certain level of perfection. Thereafter, the efforts and goals of piano makers would turn almost entirely to improving quality. Piano strings became even thicker and were wound with wire, and as a result the overall tension also increased, necessitating their need to be strung on a cast iron frame.

Many case improvements followed. In the 1860s, English manufacturers began adding veneer to a wooden frame that was made from power machines, as opposed to the previous method of hand-planing the case to the desired thickness. This was more economic and guaranteed a consistency to the case-making that ensured quality of sound and desired acoustic properties.

Yamaha has a long and rich history as one of the world’s leading manufacturers of pianos. The company released their first grand piano in 1902, one of which was sent to the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, where it received an Honorary Grand Prize. Today, we offer a wide range of models, ranging from “baby grands” (under 5′ in length) like the GB1K, GC1 and GC2, to larger instruments like those in the CX Series (the most recorded piano in history) to stunning 9′ concert grands like the flagship CFX. (For more information, see the “Yamaha Pianos” section below.)

Key Range Expansion

The first piano invented by Cristofori had only 54 keys. Most of the keyboard music of J. S. Bach can in fact be played on the 49 notes of the first pianos, but composers soon wanted more, and instrument designers responded. By Mozart’s time in the late 1700s, most pianos had 61 notes (a five-octave range). They expanded to 73 notes (six octaves) for Beethoven in the early 1800s, and eventually to the 88 notes (7 -1/4 octaves) we have today. Liszt was the first major composer to make unrestrained use of the expanded note range and increased sound volume that resulted. (Curious as to why a piano has 88 keys, and not more? Read this posting.)

Yamaha Pianos

As mentioned previously, the first Yamaha pianos were an upright built in 1900, followed two years later by the company’s first grand piano. By the 1920s, many well-known pianists were taking favorable note of Yamaha instruments, among them Arthur Rubinstein and Leo Sirota. In 1950, Yamaha released the FC concert grand to great acclaim. Eight years later, Yamaha set up a grand piano assembly line at its Hamamatsu headquarters. By 1965, the company was producing more pianos than any other manufacturer.

In 1967, the CF concert grand piano was unveiled, along with the C3 grand. Their successors, the CFIII and the CFIIIS, were released in 1983 and 1991, respectively. CF Series concert grand models made their debut in 2010, followed seven years later by premium SX Series grand pianos.

The latest line of Yamaha pianos is represented by the next-generation CFX Concert Grand, introduced in 2022. It incorporates advanced A.R.E. wood-curing technology, along with new means of connecting joints to minimize vibration loss. In addition, its soundboard has been completely redesigned and reshaped to improve the mid-bass frequencies crucial to producing a warm, rich and resonant tone.

Read more about the history of Yamaha acoustic pianos.

The Disklavier Breaks New Ground

The player piano (sometimes called a “pianola” or a “reproducing piano”) was first invented in 1896, giving people a way to have a self-playing piano in their homes during the early and mid-20th century. Composers used a special “arranging piano” to punch individual notes of songs onto a master roll. The roll would then be used to trigger full songs on the piano, with motors instead of the human hand depressing the keys.

With the debut of the Disklavier in 1987, Yamaha took a quantum leap forward. (The term “Disklavier” is a combination of the words disk [as in floppy disk] and Klavier, the German word for keyboard; at the time that the first Disklavier was introduced, recordings were stored on 3 1/2 inch floppy disks.) A Disklavier is a real acoustic piano outfitted with electronic sensors for recording and electromechanical solenoids for player piano-style playback. Sensors record the movements of the keys, hammers and pedals during a performance, and the system saves the performance data as a Standard MIDI File (SMF). On playback, the solenoids move the keys and pedals and thus reproduce the original performance.

Disklaviers also allow the user to change tempo or key with the touch of a button, thus facilitating learning even complex piano pieces. They have been used extensively in music education, including colleges, universities, conservatories, community music schools, K-12 institutions and private studios. Yamaha has also converted numerous performances recorded by prestigious composers such as George Gershwin into MIDI data, allowing those performances to reproduced with complete accuracy decades or even centuries later.

Modern Disklaviers include an array of electronic features such as a built-in tone generator for playing back MIDI accompaniment tracks, as well as built-in speakers, MIDI connectivity that supports communication with computing devices and external MIDI instruments, and additional ports for audio input and internet connectivity — there are even streaming services such as Disklavier Premium Pass designed for the instrument.

In 2016, Yamaha introduced its seventh-generation Disklavier system, the ENSPIRE, available in numerous piano sizes ranging from 48-inch uprights to a 9-foot concert grand. There are three variations in the ENSPIRE line: CL, ST and PRO. The CL is a playback-only model, while the ST and PRO models add recording and SILENT Piano™ functionality. PRO models are also capable of capturing and reproducing up to 1,024 steps of key-on and key-off velocity articulations, as well as 256 steps of incremental pedaling.

From 2650 B.C. to 2024 A.D.— that’s over 4,600 years of development. No wonder the piano is one of the most beloved instruments of all time!