The History of the DAW

The story behind the technology that changed music production forever.

The digital audio workstation — DAW for short — is a staple of today’s home and professional studio environment, offering powerful recording, editing and mixing of both audio and MIDI tracks. It has completely replaced the analog and digital tape-based formats that preceded it. Not only that, it’s largely superseded recording consoles and outboard effects processors, since it incorporates their functionality in one integrated software application, with full onscreen visuals to boot.

The advent of the computer-based DAW in the early 1990s was the result of concurrent high-tech innovation and improvements in the areas of personal computers, digital audio recording and MIDI — a perfect storm of technology.

On the occasion of the 30th anniversary of Steinberg Cubase — one of the leading DAWs on the market today, and one that was integral in the development of the format — it seems appropriate to kick off this series of blog postings about home recording basics by telling the story of how the DAW was born.

When Dinosaurs Ruled the Studio

We’ll set the way-back machine to the year 1983 to start our story. That was the year the MIDI standard was introduced to the world, making it possible to connect one keyboard with another and even to a computer. The sequencing applications that soon followed allowed musicians to record and edit MIDI tracks in their computers, and were in many ways the precursor to the modern DAW.

In those days, personal computers were primitive compared to what we have today. The Mac® was still 12 months away from its introduction (it came out in 1984) and Microsoft wouldn’t release Windows until 1985. The dominant music computers at that time were the Commodore 64 and the Atari ST, and so software developers began by releasing MIDI sequencing applications for those platforms.

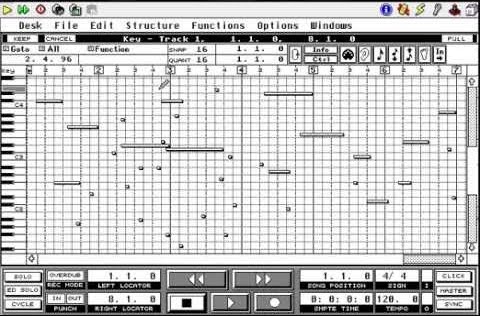

In 1984, two men in Germany — Karl Steinberg and Manfred Rürup — launched a software development company called Steinberg. (Karl was an audio engineer and Manfred a professional keyboard player.) In 1985, they released Pro-16, a MIDI sequencer for the Commodore 64 that offered 16 tracks of MIDI recording and editing. In 1989, Steinberg launched an advanced version for the Atari platform, which they called Cubase.

Turn Up the Audio

The science of digital audio recording technology was also making rapid strides during that era, though it was hardly a brand-new concept. In fact, the theory of digitizing audio actually goes back all the way to 1938. That year, a British telephone engineer filed a patent for a technology he’d developed called Pulse Code Modulation, or PCM, which was a system for converting analog signals to digital data. To this day, PCM technology is still the basis of most digital recording.

Through the 1950s and 1960s, scientists continued experimenting and trying to perfect digital audio. By the early ’70s, the technology had progressed enough that there were sporadic releases of digitally recorded albums, mostly live recordings of jazz and classical material.

By the end of the decade, digital multitrack technology started appearing in recording studios. The 3M company introduced a 32-track digital tape recorder in 1979. That year, the artist Ry Cooder used one to record Bop ’Til You Drop, which was the first digitally recorded pop album on a major label. Although that technology marked a significant step forward, the marriage of digital audio, computers and MIDI was still several years in the future.

Dawn of the DAW

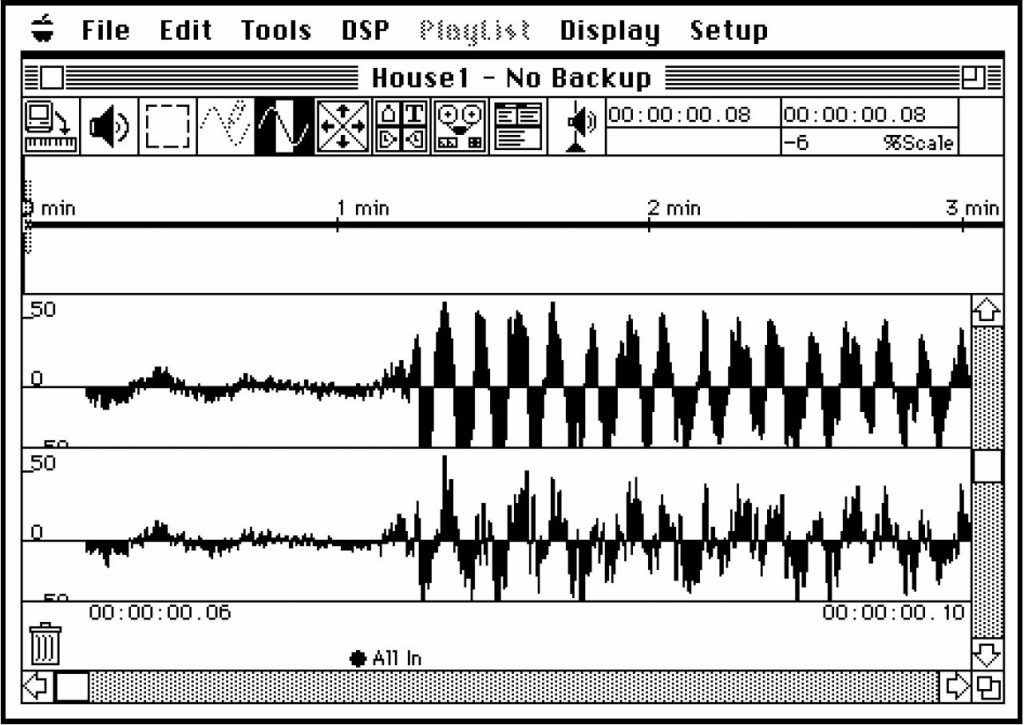

In 1989, a company called Digidesign released a Mac product called Sound Tools. This was a computer-based stereo digital audio recorder (with both a software component and a hardware audio interface) that featured non-destructive editing. This concept — where you can cut, copy, paste, move around and process the recording without affecting the original audio — represented a huge leap forward; up until that time, editing involved physically cutting and splicing analog tape.

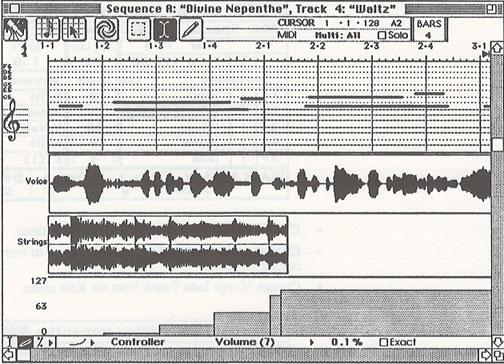

A year later, another milestone was achieved when the Opcode company released a software product (also for the Mac) called Studio Vision — essentially an update to its Vision MIDI sequencing software, but one which added digital audio recording with the use of Digidesign hardware. It was the first recording application to offer both audio and MIDI recording and editing.

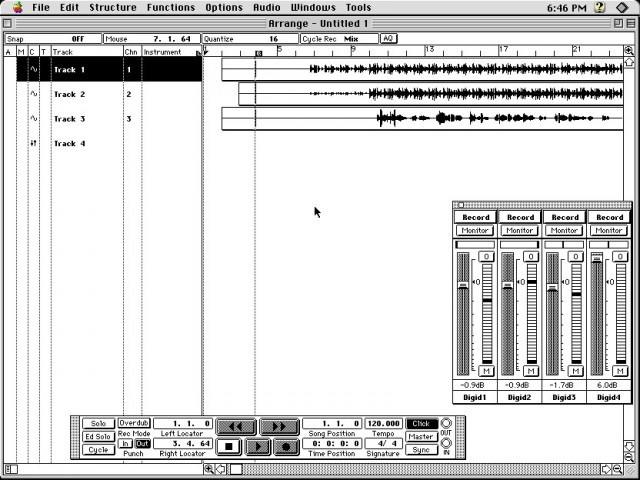

In 1991, Digidesign introduced a four-track successor to the stereo-only Sound Tools. It was called Pro Tools, and iterations of that software are still in use to this very day.

The DAW Starts Maturing

In 1992, Steinberg released Cubase Audio Mac, a computer-based digital audio recorder for the Mac that, like the Opcode products, also utilized Digidesign hardware. This was the first DAW to incorporate audio, MIDI, and scoring (music notation). In 1994, Steinberg collaborated with Yamaha to produce a Cubase software front end for the Yamaha CBXD5, a hard disk recorder that worked with Atari, Mac and PC computers.

Steinberg released another breakthrough application that year called Cubase Audio Falcon — a 16-track recorder and editor for the Atari Falcon computer. What made this product so significant was that it was the first native, computer-based hard-disk recorder, meaning that it didn’t require an external hardware device to handle the digital signal processing; instead, it used the computer’s built-in DSP capabilities.

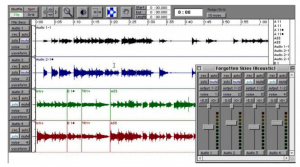

Another major innovation from Steinberg was Cubase VST, released in 1996. It introduced the native Virtual Studio Technology (VST for short) audio system and offered a whopping (for that time) 32 tracks of audio, plus integrated MIDI editing and recording, as well as numerous onboard effects and support for third-party effects “plug-ins.” It also was the first DAW to comprehensively recreate the paradigm of the modern recording studio — a multitrack recorder with an effects rack and an automated mixer. One could argue that Cubase VST signaled the beginning of the end for the analog tape-based studio.

It didn’t take DAWs very long — maybe 10 years or so — to become the dominant recording format. Their combination of high-quality audio, non-destructive editing and comprehensive automated mixing proved too much for tape-based systems, which required separate mixers and processors, and offered comparatively primitive editing capabilities.

Into the Future

Since the turn of the 21st century, DAWs have improved steadily in quality and features, as computer speeds have increased and data storage costs have dropped. Cubase remains a leader in the DAW market, and Steinberg (which was acquired by Yamaha in 2005) has also created numerous other ground-breaking and influential products for audio production.

Perhaps the most notable was the 2000 release of Nuendo, a DAW that was originally designed to meet the needs of broadcast and post-production facilities but has since become a prominent application for producing and mixing immersive audio for virtual reality and video games. In addition, Steinberg has made its mark producing hardware, with a line of quality audio interfaces (such as the recently released AXR4) that offer state-of-the-art, high-resolution audio using the latest protocols such as Thunderbolt 2.

It’s fair to say that over the past four decades, the Digital Audio Workstation has played a huge role in revolutionizing the production of audio as well as democratizing the creation of music. It’s one technological development that truly has made the world a better-sounding place!

Check out our other Recording Basics postings.

Click here for more information about Steinberg products.