Tagged Under:

Music Theory for Producers, Part 2

Chord construction basics.

In Part 1 of this two-part series, we covered rhythmic concepts that are important for producers to know. This time around, we’ll provide a quick overview of chord theory. If you’re producing music but are not exactly sure how chords are constructed or how they relate to melodies, read on!

Built on Scales

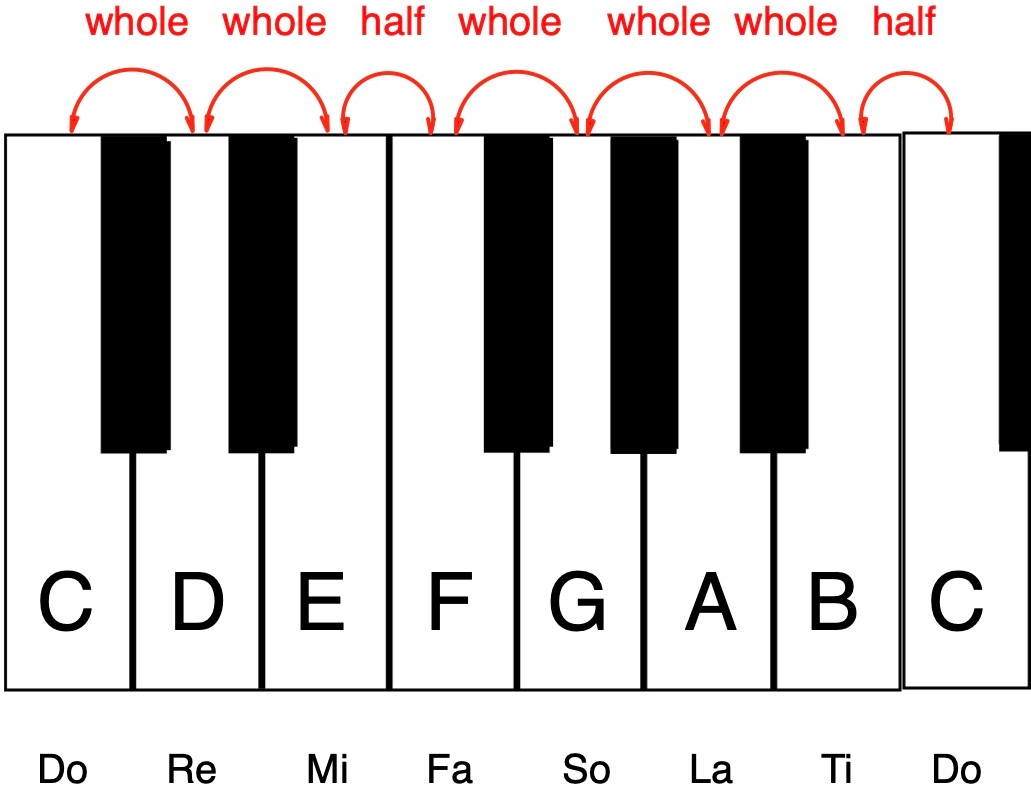

In order to understand chord construction, it’s important to have a good grasp of intervals, which are the distances between notes. In Western music, the smallest interval is a semitone, which is also known as a half-step. A distance of two half-steps equals one whole step. So a half-step above C would be C#; a whole step above C would be D, etc.

Chords are groupings of three or more notes that are played simultaneously, and they are built on scale tones (that is, notes in its scale). If you know solfege (do re mi fa so la ti do), then you know what a major scale sounds like. The key of a scale is determined by the pitch of its root note (“do”). As an example, here’s an illustration of a piano keyboard with the notes of a C major scale indicated. For additional context, the solfege equivalents are presented as well.

All major scales have identical intervals. They’re all whole steps, with two exceptions, as you can see in the above illustration: There’s only a half-step between the third and fourth degrees (i.e., E and F in this example), and between the seventh degree and the first degree of the scale in the next octave (i.e., B and C in this example).

Three is a Chord

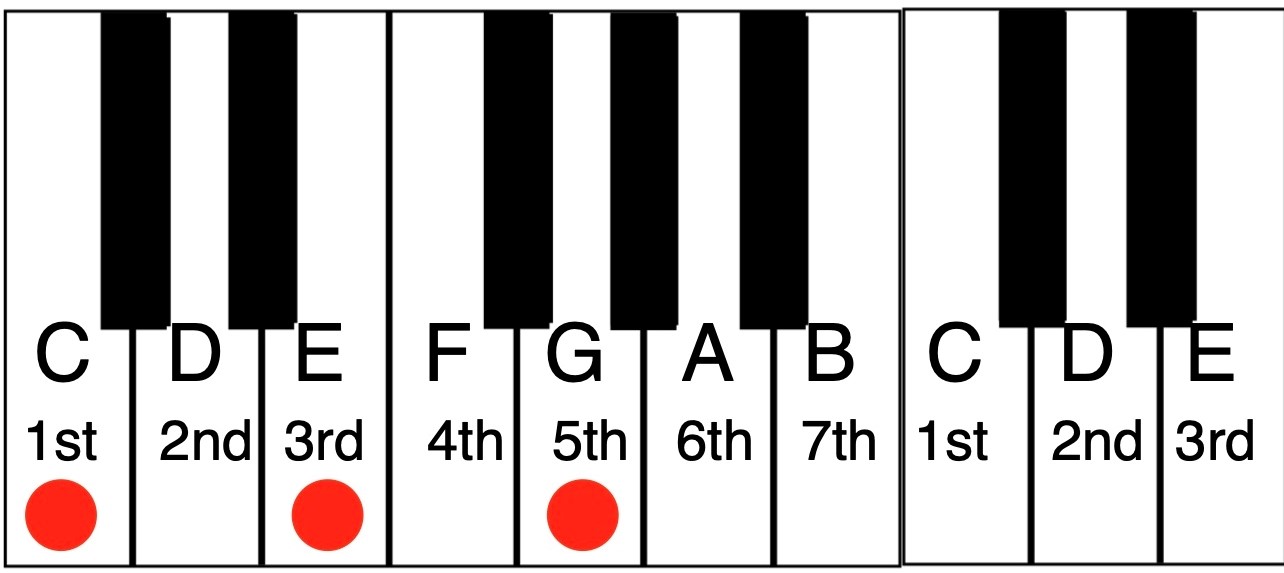

The most basic chord form is a triad. It has three notes and is a building block for more complex chords. A major triad is made up of the first degree (the tonic) plus the third-degree and the fifth-degree (dominant) tones in the scale. These are usually referred to as the “root, third and fifth.” For example, here’s a C-major triad:

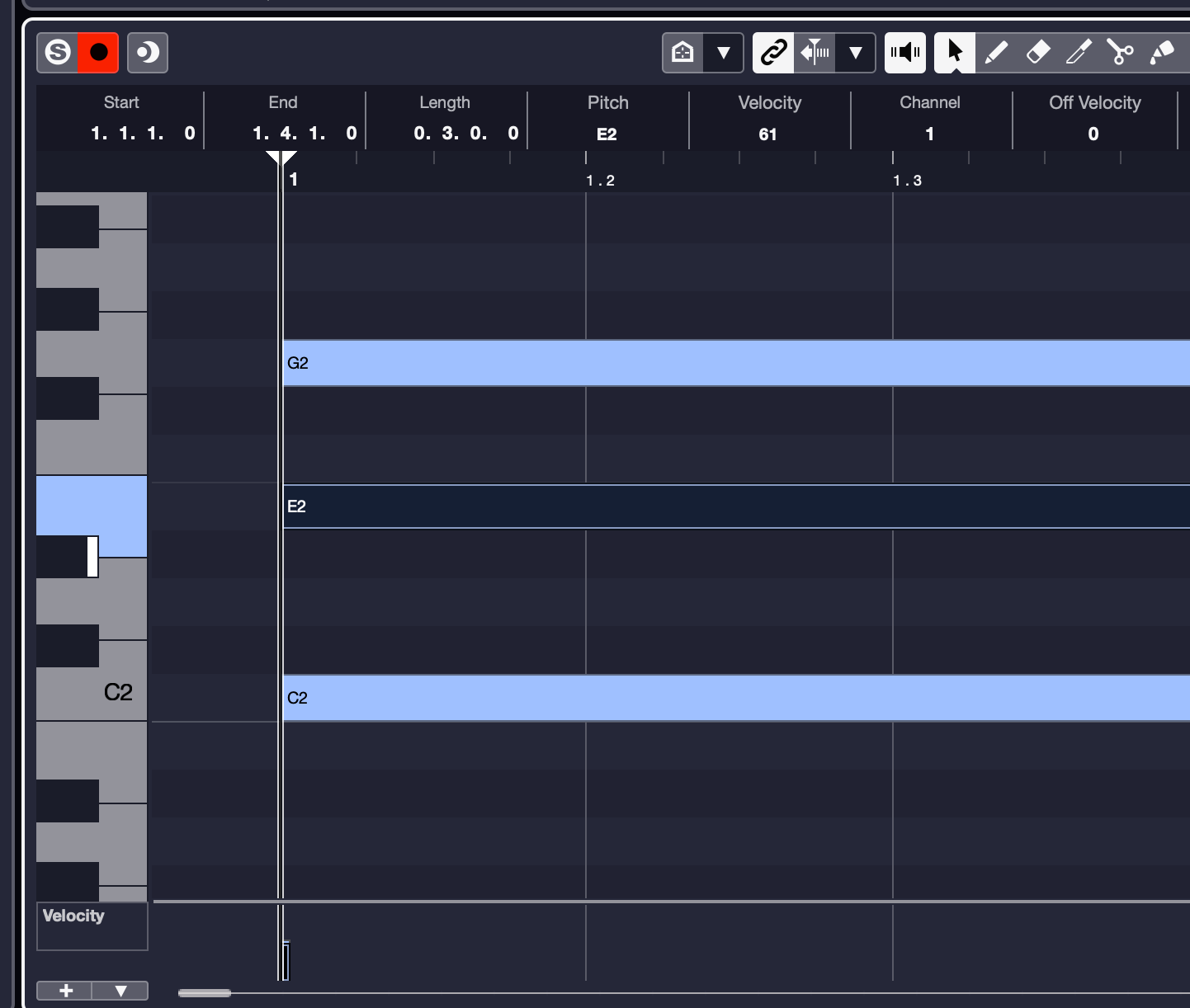

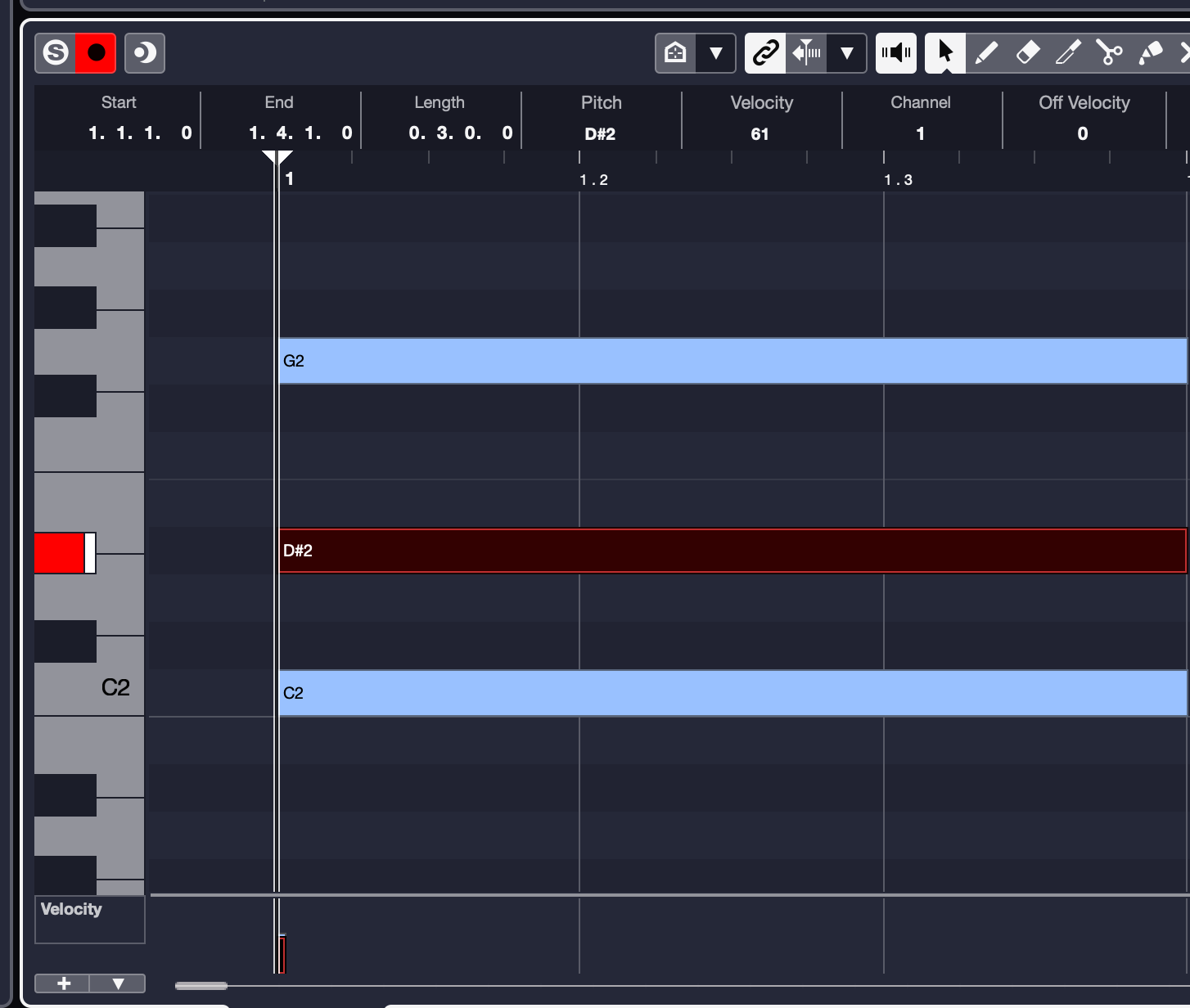

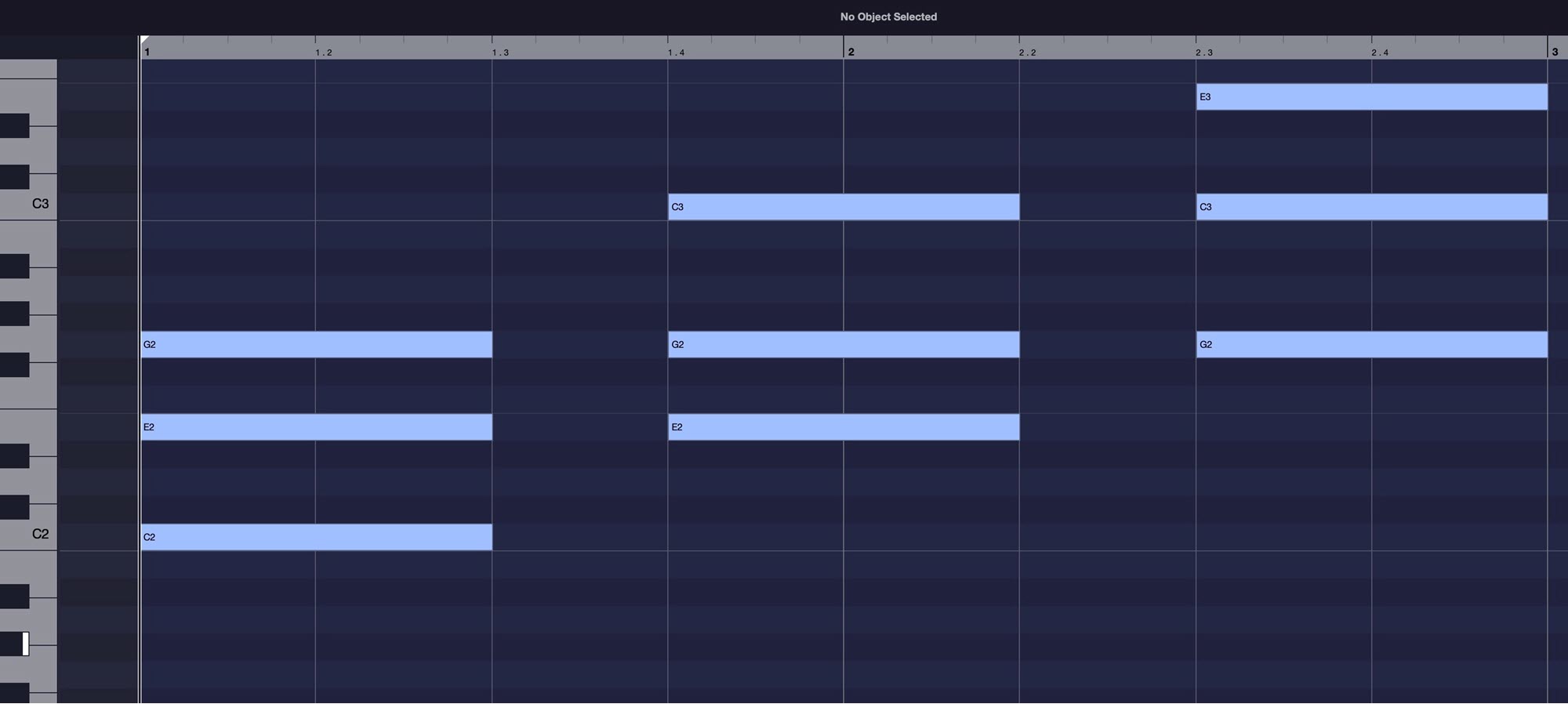

The graphic editors in your DAW show notes in the form of a piano keyboard, although they are usually oriented vertically instead of horizontally. Here’s how a C-major triad is displayed in the Steinberg Cubase Key Editor:

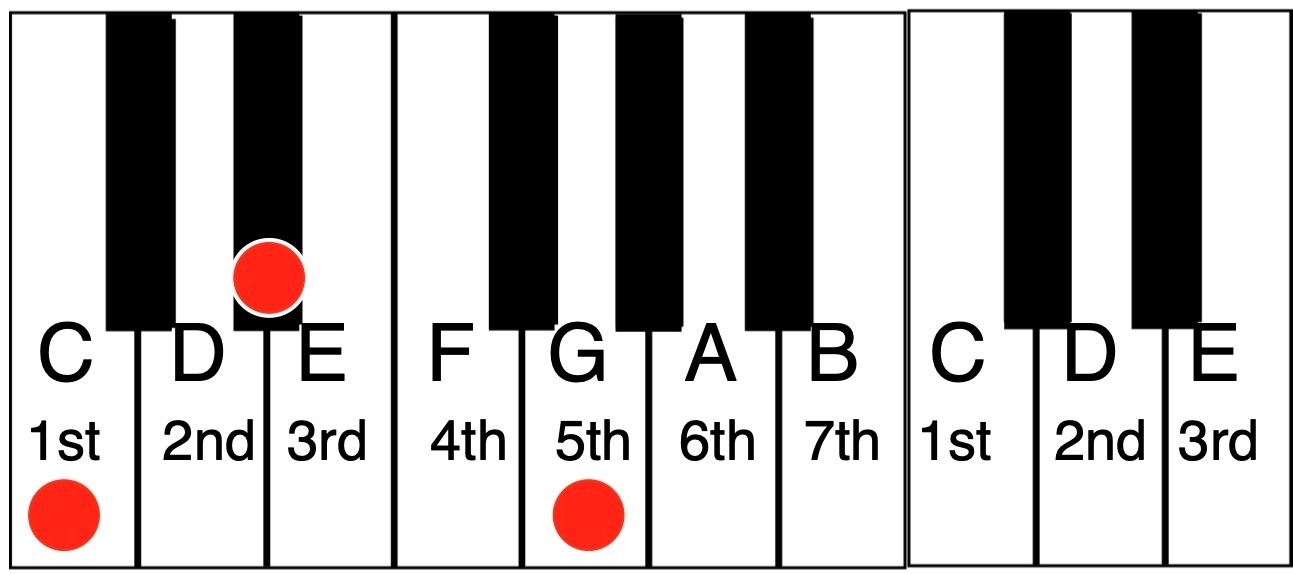

If you lower the third in a major triad by one semitone (that is, if you flat it), the result is a minor triad. Minor chords sound sad or even mysterious compared to the happy sound of major chords. As an example, here’s a C minor chord:

Here’s how that same chord looks in Cubase’s Key Editor.

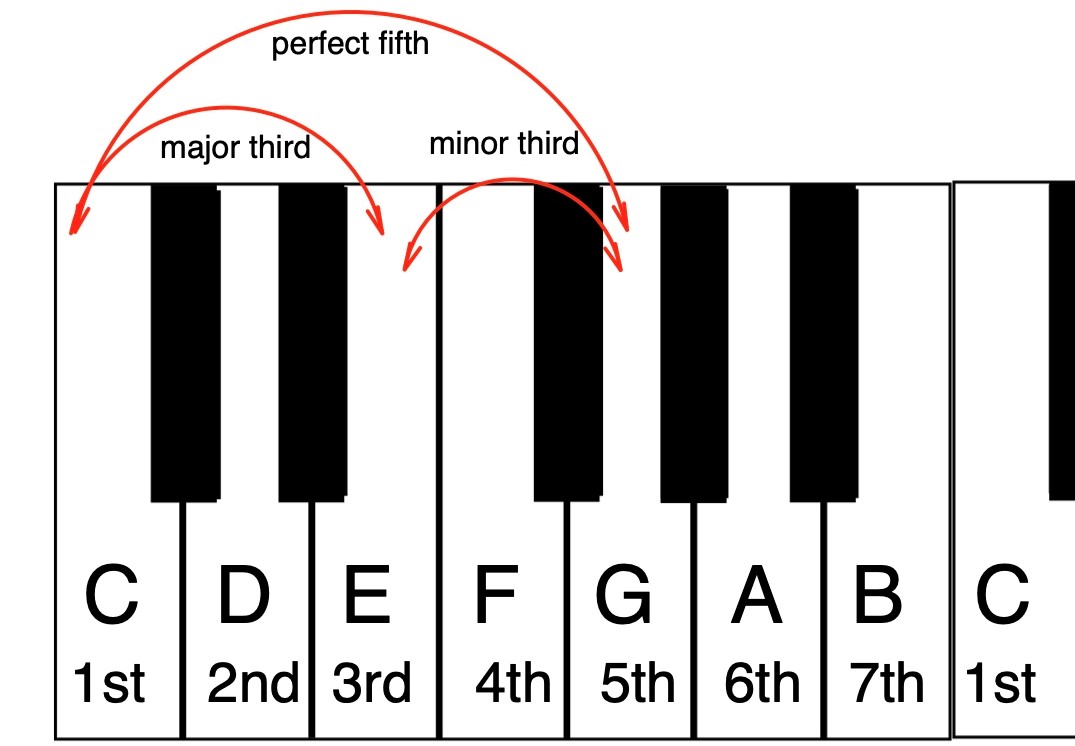

The intervals in a major triad consist of the root, a major third (the note four semitones higher than the root) and a perfect fifth (the note seven semitones higher than the root). The reason the fifth is called “perfect” is to distinguish it from flattened (“diminished”) fifths a half step lower, and sharpened (“augmented”) fifths a half step higher. (More about these shortly.)

Inversions

Inversions are chords that don’t have the root on the bottom. They’re made up of the same notes as regular (non-inverted) chords but use one of the other chord tones for the bass — a neat trick that really changes the sound. If you put the third on the bottom, it’s called the first inversion; if you put the fifth on the bottom, it’s called the second inversion.

Increasing Chordal Complexity: Sevenths, Ninths, and More

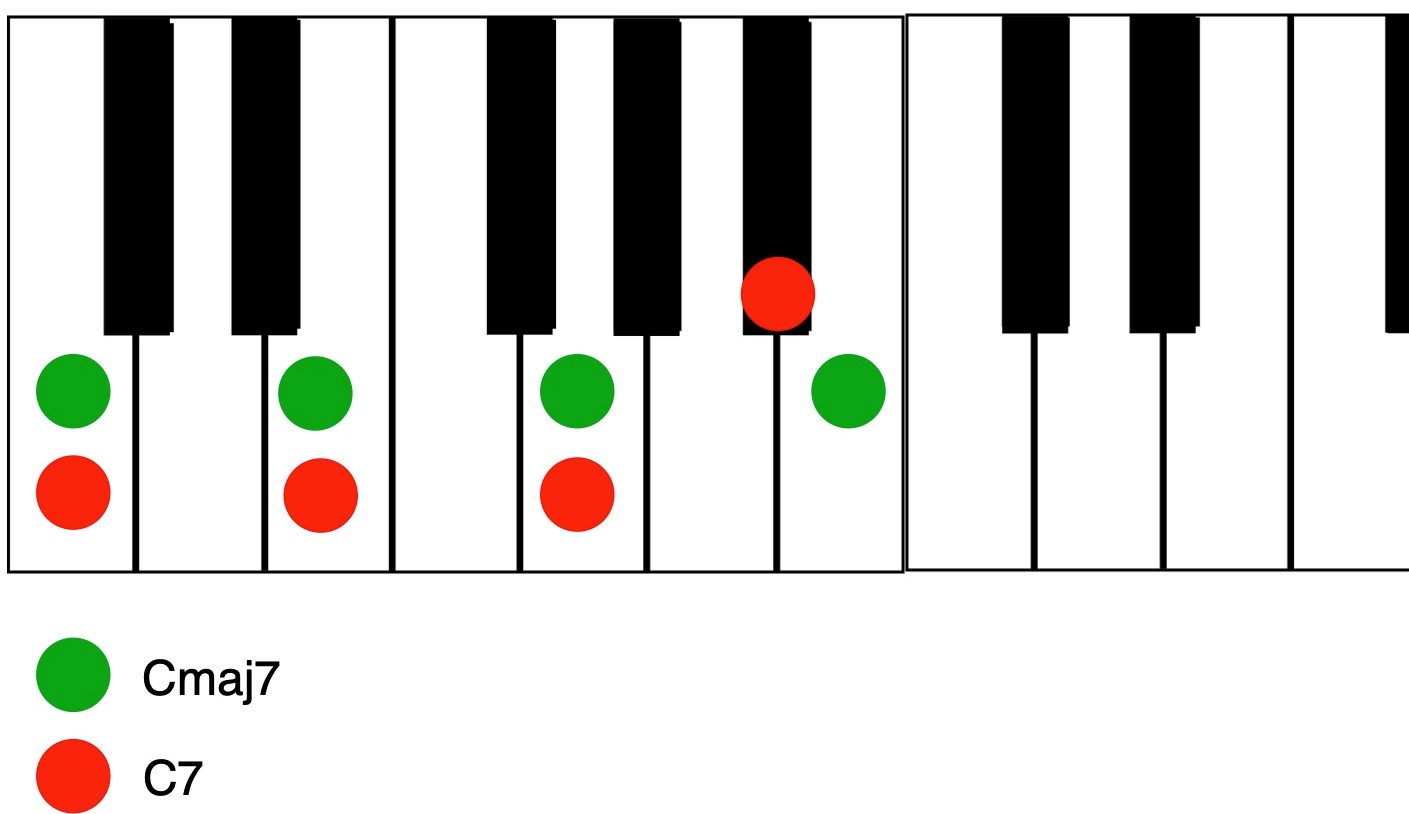

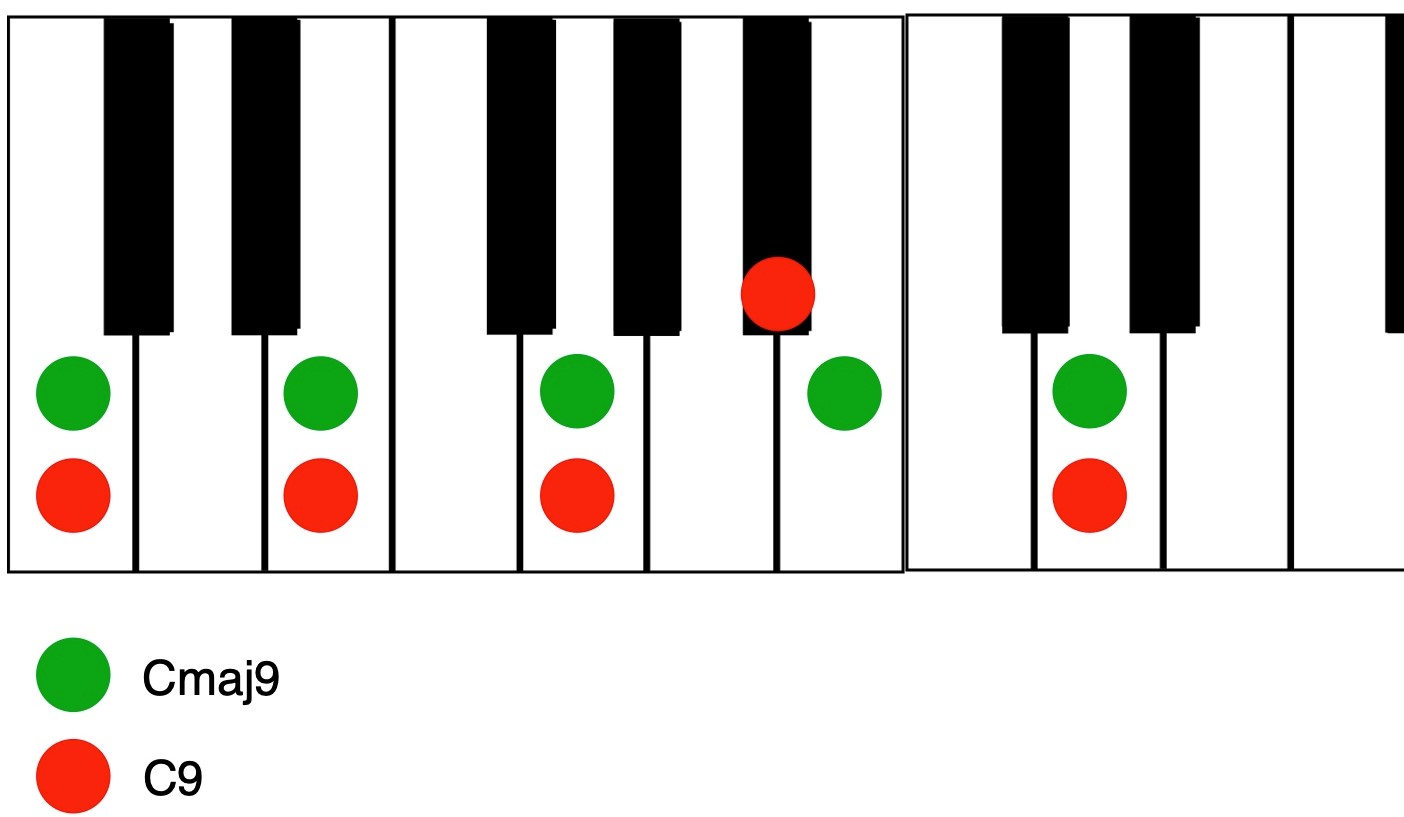

Chords sound more complex as you add notes to them. Adding the seventh degree of a major scale to a major triad gives you a major-seventh chord. These chords (indicated with a “maj7” at the end; i.e., Cmaj7) can be described as mellow or sweet-sounding. A stronger version of the seventh chord is the dominant seventh (indicated just as “7”; i.e., C7). It’s constructed the same way as a major-seventh chord except that you drop the seventh degree down by a half step, turning it into a flatted seventh.

A minor seventh chord is a minor triad plus a flatted seventh. You can build even more complex chords on top of either major or minor seventh chords. For example, a ninth chord (written as a “9” chord; i.e., C9) is made up of a dominant seventh chord with a ninth added on top. A minor-ninth chord (written as a “m9”; i.e., Cm9) consists of a minor seventh chord with a ninth added.

You might be wondering how you get a ninth when a major scale only has seven notes. The answer is that a ninth is a second (which in the key of C would be a D; in D, it would be an E and so forth) played an octave higher. Think of it this way: If you were counting up a major scale, instead of stopping after the seventh degree and starting again in the next octave, you instead continue counting. The octave above the root would be eight, and the next scale tone would be nine.

You use a similar method to create eleventh and thirteenth chords. Start with a dominant-seventh, major-seventh or minor-seventh chord and count up to the eleventh degree of the scale for an eleventh chord, or to the thirteenth degree for a thirteenth chord.

You may also run across chords with “add 9” or “add 11” or “add 13” in their name. Those are similar to ninth, eleventh and thirteenth chords but don’t have a seventh (either major or minor) in them.

Augmented and Diminished Chords

Another fairly common chord type is the augmented chord — a major triad with the fifth degree raised by a half-step. You’ll see these expressed with a plus sign or +5 after the chord name (for example, C+ or C+5).

The opposite of these are diminished chords — minor triads with the fifth degree lowered by a half-step. Diminished chords are written with “dim” after the chord name or the symbol “o” after the chord name (for example, Cdim or Co). Both augmented and diminished chords can have sevenths added to create augmented seventh and diminished seventh chords, respectively.

One other chord form you’ll run into a lot is the suspended (Sus4) chord. These are created by raising the third of a major triad by one semitone. You can also add a seventh on top to make a 7sus4 chord, such as an C7sus4. The thing about suspended chords is that they want to be resolved. In other words, after you raise the third, you should then bring it back down again. (A great example of this is Pete Townshend’s power strumming in the intro to The Who song “Pinball Wizard.”) If you don’t resolve it, it leaves the listener hanging.

Fitting In

Within any key, there are seven chords made up exclusively of notes from that key’s major scale. These are called diatonic chords. Typically, they’re referred to by their scale degree numbers and are written with Roman numerals.

The relationships between these chords are the same in every key. In the key of C, the diatonic chords are Cmaj7 (I), Dm (II), Em (III), F (IV), G (V), Am (VI) and Bdim (VII). In the key of G, they’re Gmaj7 (I), Am (II), Bm (III), C (IV), D (V), Em (VI) and Fdim (VII).

If you hear somebody refer to the “II-chord” or the “IV-chord,” etc., they’re talking about diatonic chords. You can assume that the II chord is a minor chord, the IV a major chord, and so on, unless stated otherwise (the “II-dominant-seventh” or the “VI-major,” etc.).

You may have also heard about songs that have a “I-IV-V” chord progression (for example, C-F-G). That’s typically referencing the standard chords in a blues song (as well as many rock songs). A common jazz turnaround is a “II-V” (for example, in the key of D, II-V would be Em to A). However, jazz players almost always add at least a flatted-seventh note to both chords, if not additional chord tones on top.

On Track

Steinberg Cubase has several really helpful features for dealing with chords and scales, including Chord Track, which allows you to enter the chords to your song into the measures they go in. You then can make any MIDI parts in the song conform to the specified chords. Similar features can be found in some other DAWs.

If you use Cubase’s Scale Assistant feature, you can set it to follow the Chord Track so that any notes you record will be constrained to the chord or chords in a given measure. If, like me, you’re not a good keyboard player, you can set up a chord track and then just play the same three- (or more) note chord against the whole song, and Cubase will alter the notes to fit the Chord Track.

Once you have a good handle on these basic principles, you’ll be able to analyze the chords you’re using in your productions and better understand what’s going on harmonically — which in turn can help you write more interesting chord progressions that can help make the songs stand out.

Check out these related blog postings:

Music Theory for Producers, Part 1

Major Scale Modes, Part 1: Ionian Mode

Check out our other Recording Basics postings.

Click here for more information about Steinberg Cubase.