Tagged Under:

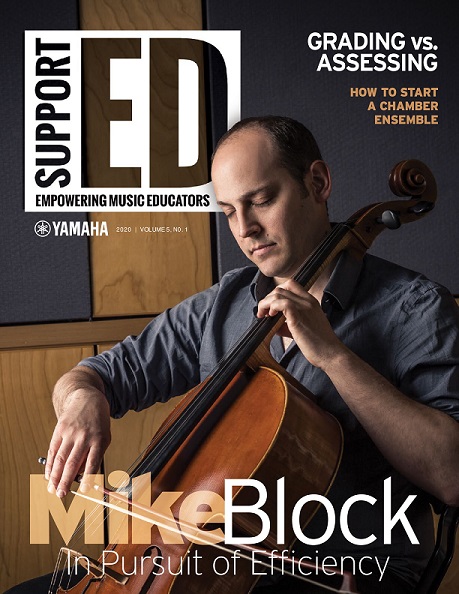

Cellist Mike Block’s Musical Quest

Cellist Mike Block’s output is staggeringly diverse, and he applies a high level of skill, commitment and efficiency into every style.

“The quest to explore different traditions from around the world outside of classical music has really felt like a quest to discover more about myself,” says Mike Block.

Block, an associate professor at Berklee College of Music and the New England Conservatory, plays the cello and sings. Other than that, he’s hard to pin down.

He has released 11 albums either as a solo artist, in a pair or trio, or as the leader of a group of musicians. The music he has tackled on his albums include bluegrass, original songs, Bach compositions alternating with modern classical music, and an upcoming duo album with an Indian tabla player.

He is part of Yo-Yo Ma’s Silkroad Ensemble and has collaborated in performance or recordings with the likes of Stevie Wonder and Alison Krauss. He’s also the first cellist to perform at Carnegie Hall standing up, using a cello strap of his own design.

Roots

Block’s father, Glenn Block, is director of orchestras and a professor of conducting at Illinois State University. His mother, Nancy Cochran, is the former director of Lamont School of Music at the University of Denver. Block’s siblings all play string instruments.

Classical music was the default — “it was what we played in the car,” Block recalls.

Other styles of music had a mystique to them — the allure of the unknown.

“The idea of popular music fascinated me as a kid,” Block says. “How can the same art form I’m studying, focusing on music from across the ocean from past centuries, … how can all these same skills captivate millions of people today?”

Despite his varied output, Block is not a sonic tourist, dipping into a style just long enough to take a metaphorical selfie. “Anything can be done poorly or masterfully,” Block says.

On his musical quest, he goes deep into whatever he’s playing, whether it’s Chuck Berry or Beethoven.

Block says he has seldom received pushback from his peers in the world of professional music although he jokes that the people who don’t return his emails probably don’t support his musical eclecticism. He adds with a laugh, “You never hear back from the people who don’t like what you do.”

Spotlight: Efficiency

How is it possible to teach, have a family, play with other top musicians, embrace a huge range of musical styles and have a steady recording career? There’s another quest behind Block’s musical one. Block is constantly in pursuit of efficiency.

“Whether it’s improvising on new jazz chord changes or trying to sing a new bluegrass song, there’s always an efficient way to learn something,” he says. “Efficiency holds intrinsic moral value for me. Inefficiency is a kind of sin rooted in a lack of appreciation for the preciousness of our time and other people’s time.”

Block laughs and adds, “I know I’m coming off quite harsh and dramatic. But, potentially to a fault, I’m always trying to design the quickest way to accomplish a goal, whether it’s the layout of my office or the pacing and structure of a workshop I’m presenting.”

Block explains that learning new things efficiently mattered to him from the beginning of his career. “I never felt like I had a huge natural talent,” Block admits. “My hope was always that I could try to catch up to everyone else.”

It’s all about working hard and working smart. Block has a firm idea in his mind of his end goal and observes other musicians for patterns or habits that he can build from. He also emphasizes breaking down a new skill into small, manageable components.

Block embraces efficiency as a teacher too. “Keeping students motivated often depends on how clearly and efficiently you can share knowledge,” he says.

Stand and Deliver

Block is an inventor and entrepreneur as well as a musician. He designed and patented The Block Strap for cellists to play while standing or moving.

Block’s friend Rushad Eggleston is known for playing cello while standing, but he uses a guitar strap. Block says that he was hesitant about giving it a try, even though he was “incredibly jealous” of Eggleston’s freedom to move around the stage.

Block explains that he used to think that “standing was Rushad’s thing. I won’t try that because people will think I’m copying him.”

One year, Block invited Eggleston to teach at the Mike Block String Camp in Vero Beach, Florida. “The morning after the faculty performance, four cellists showed up to class with straps,” Block says. “I don’t know where they got straps by 10 a.m., but they were inspired by seeing Rushad, and they had no hesitations about trying to stand and giving it a shot. I realized I was also inspired by Rushad, but I had mental baggage that prevented me from trying it.”

At first Block tried a guitar strap like Eggleston and then attempted to adjust his technique — but the results were not encouraging. “Then I had an epiphany that seems obvious now,” Block says.

The eureka moment was that he could just design a new strap to match his existing cello technique. From there, designing the right strap became a two-year-long process.

Block points out that cellists are trained to direct their arm weight into the instrument. When cellists are sitting, that force is transferred from the cello to the floor. But when they are standing, the force enters their body, creating what Block calls “a much more visceral, physical experience.”

Rebel with a Cause

Although he eventually broke free, Block says that he felt confined when he first started to take music seriously. “I was frustrated that even though I was identifying as a musician who was training for a professional career, I couldn’t do all the things musically that I wanted to do,” he recalls.

When he was playing only the selections his teachers assigned to him, he struggled to feel 100% invested in music.

“I didn’t feel empowered,” he remembers. “For me, self-empowerment comes with a streak of rebelliousness. But it’s not rebellion for its own sake, and it’s not directed at some outside authority. Ultimately what I’m rebelling against isn’t other people but the nagging voices in my own head. Living true to myself has meant examining assumptions I have about what I can do or what I shouldn’t be doing.”

Block works to make sure his own students have the freedom to pursue music in a way that empowers them, so that they can follow their own path. The key is to build on students’ existing passions and interests for various types of music and artists, rather than deciding all the repertoire for them.

As a teacher who wants to understand his students’ musical tastes, Block is constantly exposed to new sounds. He’s familiar with pop music, but he notes that his students arrive at Berklee with an unpredictable range of tastes and knowledge, remembering one student who had a deep knowledge of klezmer music (a tradition of the Ashkenazi Jews) and others who listen to cutting-edge jazz.

A Fine Line

Executing at a high level is the goal, no matter the type of music. “There’s no style that justifies playing at a lower level or not working on your technique or achieving a high level of mastery,” Block says.

He isn’t big on teaching the same thing over and over. “By the time we figure out how to teach something really well, it’s at that moment that the thing we’re teaching dies, in a way,” Block says with a laugh. “Maybe that’s dramatic language. But finding ways to give students structure and help them progress while giving them space to find themselves and find new things — I often feel that tension in teaching.”

Block says that it’s “a particularly fine line when teaching improvisation or working on arranging and composition — giving students the space to explore versus making sure they work on the skills that have stood the test of time.”

Block constructed his Florida camp to marry timeless technique with of-the-moment music. The camp, entering its 11th year, hosts more than 100 students each summer. Students who choose the popular collaborative track are first taught several pieces of music by ear, ranging from Celtic fiddle tunes to contemporary jazz. Then they form groups and are coached through arranging, improvising and performing music. “They’re learning from existing traditions, repertoire and skills, but making it their own,” Block says.

The Mike Block String Camp is a great distillation of Block’s approach to music: Creativity paired with timeless skills. Classical rigor applied across a range of musical styles.

Block’s musical quest continues, but his standards never change.

Mike Block At a Glance

- Education

- Bachelor’s: Cleveland Institute of Music

- Master’s: The Juilliard School

- Current Position: Associate Professor at Berklee College of Music and New England Conservatory

- Select Projects and Recordings:

- Mike Block String Camp

- BachInTheBathroom.com

- ArtistWorks.com

- “Step into the Void: The Complete Bach Cello Suites” (2020)

- “Walls of Time” (2019)

- “Final Night at Camp” (2018)

Photos by Eric Levin Photography

This article originally appeared in the 2020N1 issue of Yamaha SupportED. To see more back issues, find out about Yamaha resources for music educators, or sign up to be notified when the next issue is available, click here.

This article originally appeared in the 2020N1 issue of Yamaha SupportED. To see more back issues, find out about Yamaha resources for music educators, or sign up to be notified when the next issue is available, click here.