Tagged Under:

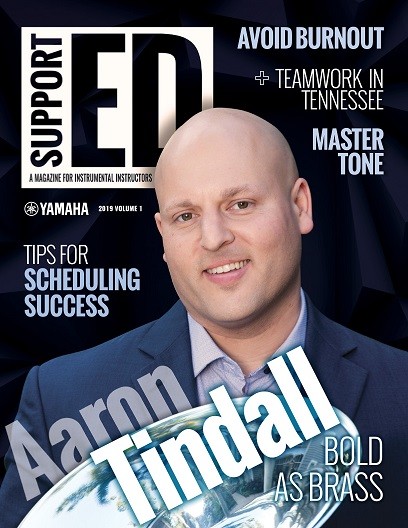

The Drive of Top Tubist Aaron Tindall

After working his way to the top of the tuba profession through relentless effort and focused planning, Aaron Tindall expects the same from his students.

“I’m kind of hard-wired to do things at a pretty intense level,” says Aaron Tindall. “In the low brass field, you just have to be relentless.” And Tindall expects the same passion from his students.

“He’s one of the most hard-working people I’ve ever met,” says TJ Graf, one of Tindall’s students. “What are you willing to do that other people aren’t? That’s his big thing. Are you willing to work on one note for two hours to play that note perfectly?”

But not that long ago, the driven Tindall was a driver — literally. “Ten years ago, I was driving limousines professionally,” Tindall says. “Whenever I had 20 or 30 minutes, I’d get in the back of the limo and practice on the tuba.”

Tindall was taking a semester away from graduate school. Practicing between customers was “the only way to keep my hope and dream alive to be the player I wanted to be.”

Tindall’s road to the top of his profession has not been smooth or straight, but his persistence has made the difference. He is currently associate professor of tuba and euphonium at the University of Miami Frost School of Music. In the summers, he teaches at the Eastern Music Festival in Greensboro, North Carolina. His fourth solo album, “Yellowbird,” comes out later this year.

These accomplishments are particularly impressive given the fact that Tindall didn’t focus on the tuba until his mid-20s. An accomplished euphonium player, Tindall added the tuba when confronted with the daunting prospects of earning a living playing the smaller instrument. “It was all or nothing,” he says, with euphonium players either getting plum positions in military bands or having to find work outside of music.

Tindall was able to play F tuba at the time, but he was very far from having the full tuba toolbox. “I knew in order to be a college professor, I needed to learn to play the tuba just as well as any other tuba player could,” he recalls.

Keep the Ignition Switch On

Getting better each day in steps that are carefully plotted on a mental map is the Tindall way. “One of my favorite expressions is: ‘Some people dream of success while other people wake up and work hard at it,'” he says.

As a teenager, Tindall trained Labrador retrievers for field competitions. He twice won national titles. That experience fine-tuned his approach toward success. “It’s just systematic,” Tindall says. “You can’t move to step two unless you’ve done step one really well.”

Tindall says that he expects his students to “have a clear game plan of what they’re going to do the next day” before they go to sleep. “They need to know what their warmup routine is going to consist of. Every hour of their day needs to be mapped out.”

Tindall practices what he preaches. Each night he plans what he will do the following day, finding a way to divide his time among his family, his students, his busy performance schedule and his own practice time.

When asked if there’s a certain personality type that thrives playing the tuba, Tindall pauses. “There’s a certain personality that thrives working with me,” he says with a laugh.

“The most important thing is work ethic,” he adds. “Everybody’s on a different trajectory, everybody’s on a different pace of learning, everybody starts at a different point. But I really want to find a student who will keep that ignition switch on week after week.”

Tindall says he works best with hyper-focused students. “The music field is incredibly tough. The minute that switch gets turned off, a lot of students quit trying as hard, and they don’t practice with the same determination,” he says.

Tindall is unapologetically intense about music, but his students are quick to call him caring, supportive and kind. They note that he applies his energy and focus to supporting them as people, not just as players.

Firing on All Cylinders

While he was in graduate school, Tindall won a prestigious solo competition and with it a scholarship to attend the Aspen Music Festival in Colorado. At the time he was exclusively a soloist. Tindall bought an orchestral tuba just two days before the festival started.

From that start, Tindall has become an accomplished group player. He’s now the principal tubist for the Sarasota Orchestra. “When you sit on a stage with 80 to 90 of your colleagues who are all performing at a high level, and you get to churn out this creation, a masterpiece, that’s pretty thrilling,” he says.

Tindall says that his orchestral role is “to take the low end of the brass and the low end of the woodwinds and meld that into the strings. Sometimes I have to sound like wood, sometimes I have to sound like metal, sometimes I have to sound like a strings player. The role of a tuba player in an orchestra is so diverse.”

He embraces the tuba’s prominent voice in a group and its role creating a rhythmic and harmonic foundation. “I love the pressure of it,” Tindall says. “I thrive on it. If I’m not on my game, everybody is going to know it.”

One vitally important performance principle that Tindall imparts to his students: “When things are consistent, things are authoritative. When things are authoritative, people listen.”

Road Map to Success

For his students, Tindall maps out challenging daily goals. “I ask them to practice four to five hours,” he says.

The day begins with an hour to an hour and a half of their “daily fundamental routine, where they’re working on their mechanics of playing,” Tindall says.

He likes his students to get this done first thing, before 9 a.m. Next is 30 minutes of working on “whatever their deficiency is.”

His students spend one hour practicing an etude, with different pieces each day of the week. “They’re learning how to deep practice something,” he says.

A recording device is an essential tool for musicians. “Record, listen, fix,” Tindall says. “That’s the mantra.” At the end of the hour, they perform the piece for themselves, recording it for future critiques.

The next hour they study solo material, using the same record-listen-fix process. Then comes an hour of orchestral or military band excerpts — “job material,” in Tindall’s words.

Tindall knows that not all of his students will have careers in music, “but the lessons that they learn in the music field are invaluable,” he says.

Time management, perseverance, high expectations and relentless effort are some of the traits Tindall works to build in his students. “Where else can you learn to be a leader and a follower, a collaborator, a doer, a team player, a problem solver?” he asks. “Sometimes we don’t do a good enough job marketing all the skills people learn from studying music.”

It’s no surprise that Tindall is methodical about imparting life lessons. He has developed a list of ways to build your self-concept. These include:

- Value who you are as a person over who you are as a musician.

- Value the idea that you can contribute to others.

- Set realistic expectations on a daily, weekly, monthly and yearly basis.

- Set aside perfection and instead learn from your accomplishments and mistakes.

- Learn the difference between critique and criticism. A critique is a detailed evaluation of something while a criticism tends to be a negative reaction.

- Don’t lose your self-identity. Hold on to your roots and the good things about where you came from and build on those.

- Stay humble as you succeed. As pastor Rick Warren said, “True humility is not thinking less of yourself; it is thinking of yourself less.”

It comes down to drive — keeping the ignition switch on — and driving — following a map. It’s a good way to get places. And it’s clearly worked for Aaron Tindall.

AARON TINDALL AT A GLANCE

Bachelor’s: Penn State University

Master’s: Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester, England

Doctorate: University of Colorado Boulder

Additional Studies: Indiana University

Solo Recordings

- “Songs of Ascent” (2010)

- “This is My House” (2015)

- “Transformations” (2016)

- “Yellowbird” (2019)

photo by Rob Shanahan for Yamaha Corporation of America

This article originally appeared in the 2019 V1 issue of Yamaha SupportED. To see more back issues, find out about Yamaha resources for music educators, or sign up to be notified when the next issue is available, click here.