Tagged Under:

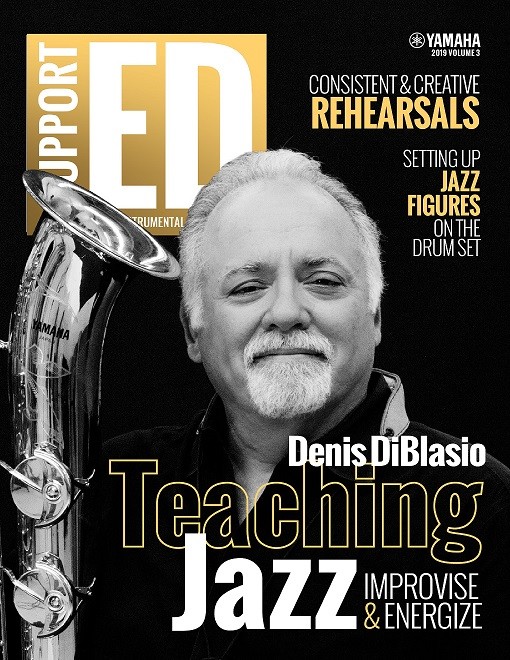

Denis DiBlasio: Jazz Saxophonist, Music Educator and Storyteller

Denis DiBlasio’s life in jazz and teaching has been full of improvisation, invention and reinvention.

Denis DiBlasio is a natural improviser. He was about 10 years old when his music teacher wrote down a blues scale in F.

“He said, ‘Just make up stuff and use these notes,'” DiBlasio says. “I must have played that thing for two years. I just beat that thing to death.”

After spending so much time on the F scale, “I was upset when I found out there were 11 others. I thought I was ready for the road,” he jokes.

Humor and self-deprecation are big parts of the DiBlasio persona. He can poke fun at himself, knowing his reputation as one of the leading jazz saxophonists of his era is secure. DiBlasio spent many years playing with legendary bandleader Maynard Ferguson and is currently the executive director of the Maynard Ferguson Institute of Jazz Studies at Rowan University in Glassboro, New Jersey, where he also leads the jazz studies and composition program. In addition to teaching and playing the baritone sax, DiBlasio is a flautist, arranger and composer.

“Fun is a Great Motivator”

DiBlasio stepped into music rather than being pushed into it — though his parents were always supportive and enjoyed hearing him play. “I didn’t have a piano-playing mother who was like, ‘You need to do this, or you need to work like that,'” he says. “What was really important is that I was left on my own to figure it out, to play with it on my own. It was always my thing.”

Music appealed to DiBlasio for a simple reason, one that might seem radical in today’s overscheduled world. “I just think it was something that was fun, like other things were fun,” he says. “I don’t want to say practice wasn’t a chore, but there were times when I practiced a lot, and there were times I didn’t. I was a kid. I’d put it down for about a month, fool around, play sports, and I’d pick it up later.”

DiBlasio is quick to note that fun isn’t the same thing as a free-for-all. “I knew early on that the better you became, the more fun it was,” he says.

Learning to play an instrument takes discipline, and being a professional means many days consumed by hours of practice. But DiBlasio emphasizes that the point of all that work was always enjoyment.

“Fun is a great motivator,” he says. “[But] fun doesn’t mean you’re goofing around. You’re working hard. You’re working really hard. Coltrane practiced 11 hours a day. He didn’t do it because he hated it. He did it because he was driven. He loved it. Call it love, call it fun, call it whatever.”

DiBlasio didn’t commit to a life in music until he needed to choose a major in college at Glassboro State College (now Rowan). Other options included becoming a marine biologist or a veterinarian. He quickly realized that he didn’t want to be a vet. “There was too much math in it,” he says with a laugh. “I didn’t realize it was science. I thought you just played with animals.”

“All Juiced In”

So DiBlasio stuck with the sax. “The more you stay involved, the more you get involved,” he says. “Before you know it, you’re all juiced in with all these different activities, and you know a lot of people. … You have a big, wide-open group of friends. And it kind of went from there.”

After getting his master’s in studio writing and production at the University of Miami, DiBlasio earned a spot in Ferguson’s high-profile band. Even though he was a full-time touring musician for only about five years, DiBlasio continued to play on and off with Ferguson for decades.

After getting his master’s in studio writing and production at the University of Miami, DiBlasio earned a spot in Ferguson’s high-profile band. Even though he was a full-time touring musician for only about five years, DiBlasio continued to play on and off with Ferguson for decades.

DiBlasio describes Ferguson as a “musical big brother.” The bandleader’s career started in the 1940s and continued up to his death in 2006. Ferguson was, at different times, a session player for Paramount Pictures, a close associate of counterculture figures Timothy Leary and Ram Dass, an inventor of new brass instruments, a successful recording artist, and, of course, a bandleader who played all over the world and developed a reputation for nurturing young talent.

Part of the way DiBlasio keeps Ferguson’s memory alive is by telling stories. “Just go to YouTube and type in my name,” he says. “I posted about 30 stories about Maynard.”

DiBlasio has embraced the video-sharing site. He’s posted instructional videos on a range of topics. They’re short, funny and loaded with great suggestions. In fact, DiBlasio says that people who find him on YouTube often reach out to ask him to teach or perform. “They don’t know who Maynard is, and they definitely don’t know about my career,” he says. “But they’ve seen the videos.”

DiBlasio credits his time in Ferguson’s band with launching the rest of his career. “Everything kind of blew up after that, doing clinics and concerts and teaching,” he says.

But it’s not as simple as saying he became a teacher and enjoyed his happily ever after. It’s work.

“Nothing’s Wrong with Them!”

DiBlasio says that every five to seven years, he has to come up with a whole new way of teaching. “The way I’m teaching now has nothing at all to do with the way I used to teach,” he explains. “The 19-to-22 age range isn’t the same as 19 to 22 was when I started.”

For DiBlasio, teaching is a partnership with each student. In the same way that he changes the way he performs based on who he’s playing with and the audience, he changes the way he teaches based on what his students know and care about and their life experiences. “You have to tune in to them,” he says.

He remembers when students knew jazz greats like Buddy Rich, Count Basie, Duke Ellington and Woody Herman. But for many students today, “Count Basie might as well be Beethoven,” DiBlasio says.

He sometimes sees new teachers taken aback by how little their students seem to know about jazz, but DiBlasio sees this inexperience as an opportunity. “There are an awful lot of people who are interested in music but don’t know much about it,” he says. “As a teacher, you’re trying to bring them into it.”

DiBlasio says a typical reaction of a new teacher is: “These kids don’t know Count Basie. What’s wrong with them?”

DiBlasio practically roars his rhetorical response: “Well, nothing’s wrong with them! They’re fine!”

“Making Small Adjustments”

But DiBlasio readily admits that he went through a painful awakening. A few years after he started teaching, he complained to his wife. “I was resenting it,” he says. “I was saying, ‘These kids don’t get it.'”

At the time, his wife, Hilda, was teaching preschool children with learning disabilities or behavioral challenges. DiBlasio recalls that she lovingly dressed him down: “She told me, ‘You only know your topic. You know what it is. You don’t know what teaching is. Everybody knows content. Ninety percent of teaching is getting their attention.'”

Hilda went on to explain that a different tactic is needed with 3- to 5-year-old students with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). “She told me, ‘You want to teach them to count? You have to figure out how to make them want to,'” he said.

DiBlasio tells the story gleefully. “If you want pity, don’t marry a smart woman.”

But the humor masks a devotion to teaching and a huge heart for his students. It takes constant self-care to keep teaching fun. “Having a great attitude about teaching doesn’t mean that all your days are going to be great,” he says. “You have to work at liking it. It’s like tuning an instrument or paddling a canoe. It only looks like it’s going straight, but really you’re making small adjustments all the time. That’s what teaching is, at least for me. … If you’re not flexible as a teacher, you’re done.”

Like playing jazz, teaching involves listening and reacting. “You’re a psychiatrist one day, a coach the next day, the next one you’re their friend, the next one you’re their dad,” DiBlasio says. “If your radar is up and picking up their signals, you find yourself changing a lot. That’s what’s exhausting. Not that they don’t deserve it. They’re good kids; they’re great kids. I love it.”

Photos by Rob Shanahan

This article originally appeared in the 2019 V3 issue of Yamaha SupportED. To see more back issues, find out about Yamaha resources for music educators, or sign up to be notified when the next issue is available, click here.