Tagged Under:

Step Up To A Better Mixer

How to know when it’s time to move up to a pro-level mixer.

The mixing console is the most important component of your PA system, acting as a central hub for all audio inputs and outputs. If you’ve been thinking about upgrading, here are some signs that you’re ready to make the move.

You Need More Inputs

Running out of inputs is a big indication that you’re outgrowing your current console. Maybe your band is playing larger venues and you’re ready to mic the drum set, or you’ve added playback tracks to your show. Or maybe you need extra microphones for a special worship service. No matter the reason, you’ll need inputs to accommodate those sources.

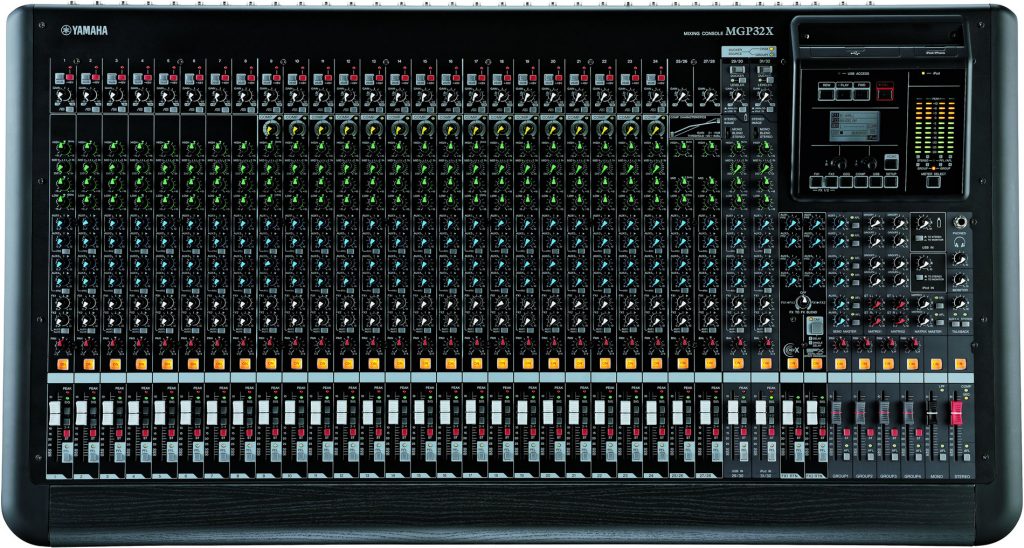

The mixer is typically the most expensive component of a PA system, so plan for the future with one that has more inputs than you need right now (it’s amazing how fast those extra channels fill up!). For example, the Yamaha MGP32X analog console offers 24 microphone inputs, plus four stereo line inputs, which should be sufficient for most venues. Although most analog mixers cannot be expanded, many digital ones (including all Yamaha TF and Rivage PM Series mixers) offer optional expansion racks and cards that can increase the input and output channel counts.

You Need More Outputs

As your band starts playing bigger venues, you might want separate monitor mixes for each musician. For example, the drummer may need to hear a click for playing along with pre-recorded tracks, but the rest of the musicians may not want to hear the click. Pro-level mixers generally offer more aux send outputs than beginner mixers. Both the Yamaha MGP32X and MGP24X models provide six aux sends with individual XLR outputs that can be used for creating monitor mixes, plus they have two internal effects sends.

Additional outputs found on pro-level mixers like the MGP24X include a mono output (useful for feeding a subwoofer), extra stereo outputs for connecting auxiliary speakers, group outputs for patching into a recording device, and matrix outputs that allow you to combine different mix buses for specialized applications like streaming to the web.

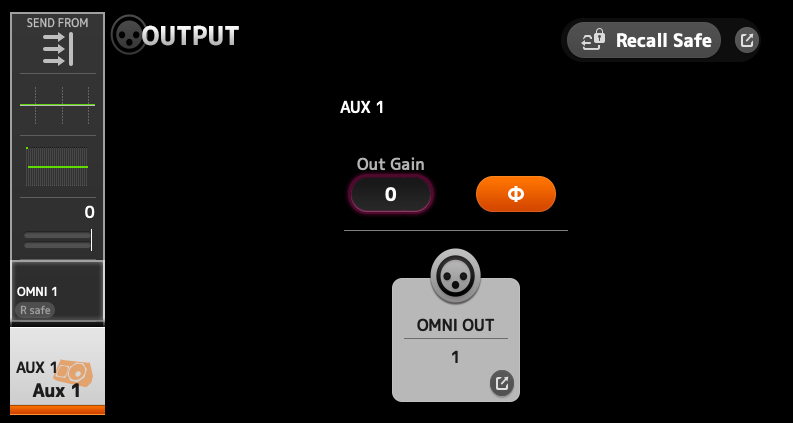

Digital mixers often have assignable “Omni” outputs — a feature that you won’t find on an analog mixer. Yamaha TF Series mixers provide 16 XLR Omni outputs that can be user-assigned to the L/R mix, aux sends, or matrix outputs.

Inserts

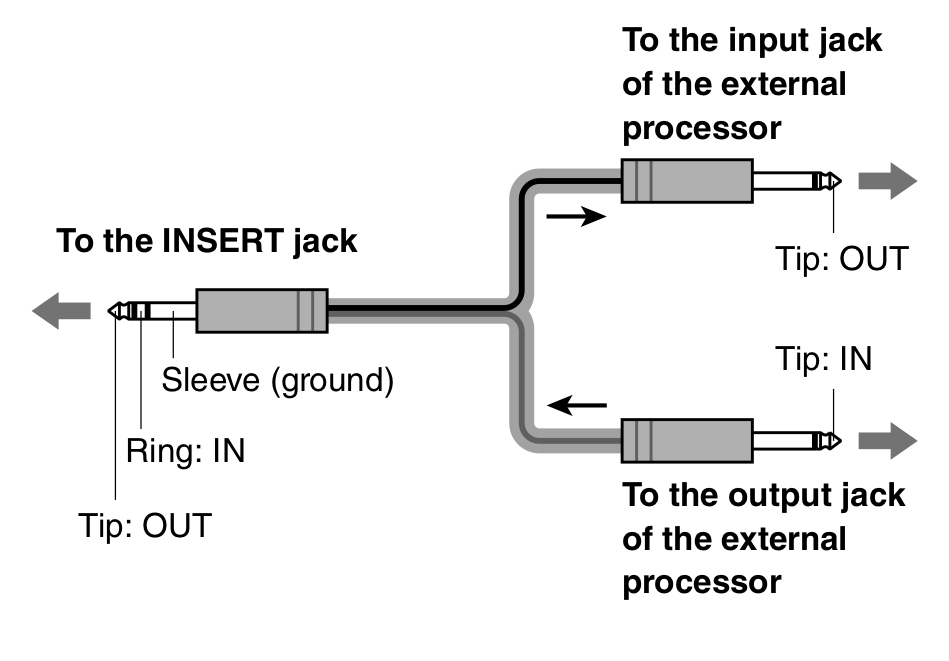

An insert is a special connection on a mixer that allows an external processor such as a compressor, noise gate or equalizer to be patched into a specific channel. Inserts are usually found on input channels, but many pro-level mixers also provide inserts on the main L/R output and the group outputs. Inserting a processor on an input or output channel allows you to optimize the settings of the processor for that specific channel — though the processor cannot be “shared” with other channels.

The inserts on an analog mixer often use a single 1/4-inch TRS jack as both an input (send) and an output (return) at the same time, and connect to the processor using a special insert cable, wired as shown below.

Yamaha TF and Rivage PM Series mixers provide onboard digital effects (see below) that can be inserted on a channel, without the need for external patching.

A Wider Range of Effects

Entry-level mixers usually provide just one or two onboard effects processors with a limited selection of effect types. Pro-level mixers — particularly digital models — feature comprehensive virtual effects racks that can greatly expand your sonic palette by allowing you to create unique effects for different instruments. For example, you could have one type of reverb for the drums, another reverb for the lead vocal and a third for the horns, each optimized for their respective instrument. Virtual effects racks also allow individual effects to be digitally inserted as described above. Many digital mixers offer a wide range of effects, including pitch shift, chorus, flange, phaser, stereo delays, and a variety of different reverb types such as plate, hall, room, chamber and reverse reverb.

Advanced Routing Capabilities

Pro-level mixers, particularly digital consoles, also provide routing flexibility you won’t find on entry-level mixers, such as audio groups, pre/post switching on the aux sends, and the ability to route effects into monitor mixes.

Audio groups (also called “subgroups”) make it easy to manage a large number of channels. As an example, let’s suppose you have ten channels of drums and want to make the entire drum set louder. Trying to move each fader by the same amount will prove frustrating and inaccurate. Grouping those channels together, however, enables you to control their level with just one fader (or two if you want a stereo group).

Digital mixers often provide a special type of group called a DCA or “Digitally Controlled Amplifier.” Unlike an audio group, a DCA is not an audio path — it adjusts the level of each channel individually, as opposed to summing all the channels into one.

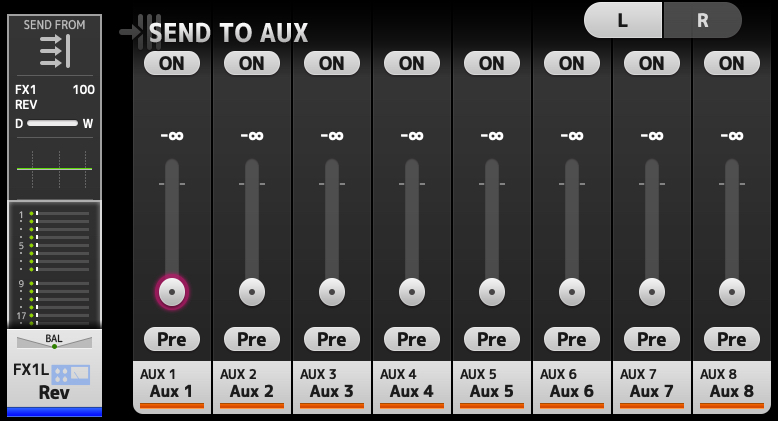

Most digital mixers and some high-end analog mixers (for example, the Yamaha MGP24X/32X) also offer aux sends that can be switched between pre-fader and post-fader, making them equally useful as either effects sends or monitor sends.

Another type of advanced routing that you won’t find on an entry-level mixer is the ability to send effects to the aux sends. This enables you to add reverb or other effects to the monitor mixes, which can help inspire a musicians’ performance.

Talkback

Talkback is a special channel designed to help an engineer communicate with musicians on stage. Much more effective than yelling from the front-of-house mix position to the stage, a talkback microphone is routed into the aux sends so that it can be heard through the musicians’ monitor mixes. Most pro-level mixers offer this feature, providing an XLR input for the talkback mic, assignment buttons for routing the microphone into the aux sends, a level knob for controlling the volume of the talkback mic, and an on/off switch. A stereo assign switch for the talkback mic (again, found on many pro-level mixers) can be handy if you need to make an announcement over the PA system from front-of-house.

Improved Memory Capacity

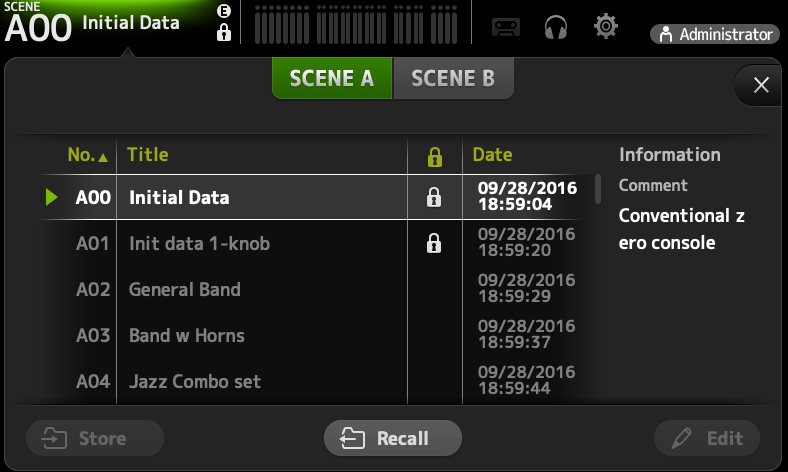

One of the big advantages of using a digital mixer is recallability. Digital models can usually store and recall every setting on the mixer as a “scene” or “snapshot,” and many allow you to create libraries of channel settings, effects or EQs. Scenes can be created for each song and then sequenced to build a show. You can create different scenes for different venues, or for different performers in the same venue — which is particularly helpful in House of Worship applications where services may have different musicians and/or ministers. Scene data can usually be stored to and recalled from a thumb drive, allowing you to carry the data with you and load it into another console.

Remote Control

A feature that you won’t find on entry-level mixers or any analog mixer is remote control via network. Many digital mixers can be controlled using a smart device, which opens up a world of possibilities. You can walk the room while controlling a Yamaha TF mixer from an iPad, and adjust your mix based on different listening positions. In addition, musicians can control their own monitor mixes from a smart device using apps like Yamaha MonitorMix, which supports the use of up to 10 smart devices simultaneously. MonitorMix provides each musician with personal control of their mix, reducing the workload on the front-of-house engineer.

As you can see, stepping up to a better mixer not only provides a greater range of sonic possibilities, it can also mean more options for taking control of your performances as you step up to bigger and better gigs.