The SILENT Guitar Speaks

My first experience with a Yamaha SILENT Guitar™ was back in 2012 while filming a new guitar instructional course for the online video company Truefire. We wanted to capture the sound of a classical/nylon string guitar as quickly as possible and a SLG100N was on hand in the studio. I turned the guitar on, set all of the controls to center detent, fine-tuned the guitar using the onboard tuner, set input levels and we recorded the guitar using its onboard reverb and delay effects for a little ambience. The session ran smoothly, we captured some great sounds that day and the guitar looked much better than I did on camera!

Since then, I’ve been a fan of the SILENT Guitar, using my SLG200N for studio sessions, live performance and travel.

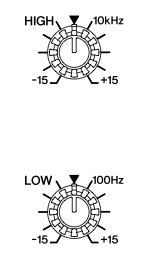

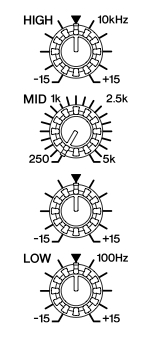

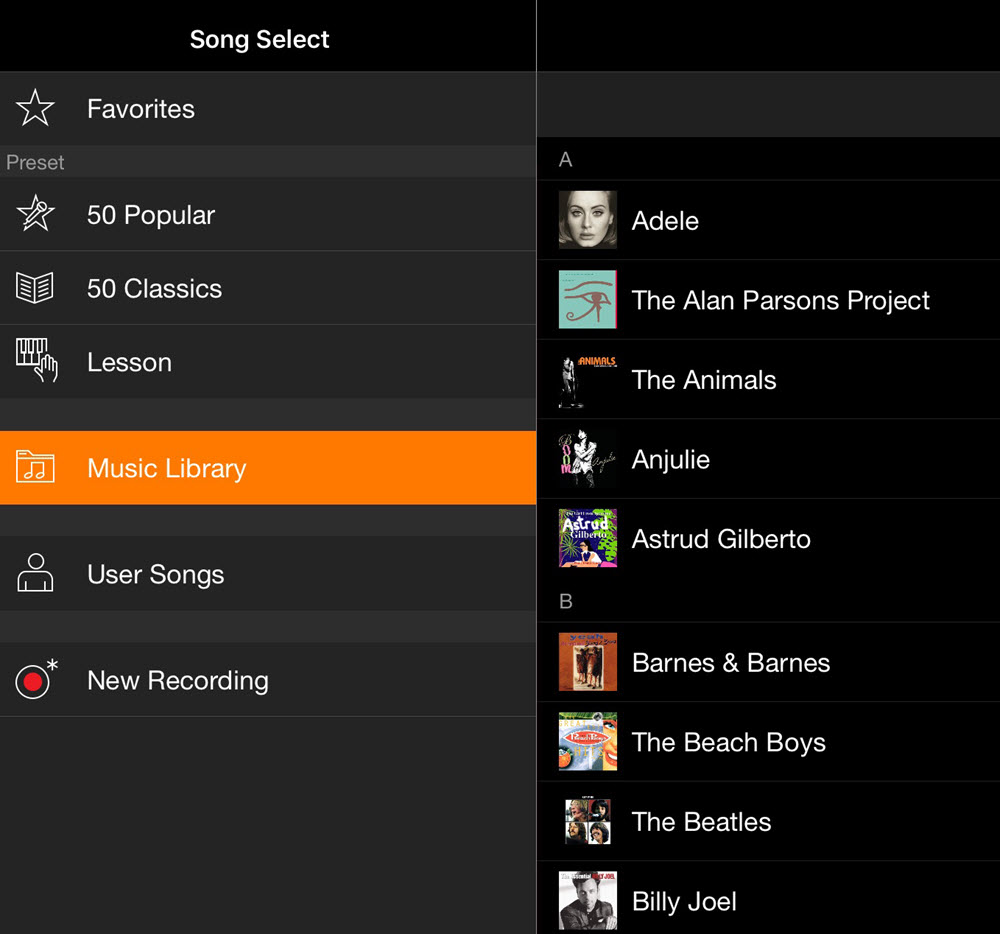

SILENT Guitars are packed with features, including a chromatic tuner, reverb, chorus, tone controls, an SRT mic and piezo blend control, and an aux input for smartphones and MP3 players. Monitoring all of these features via the supplied headphones makes this the ultimate guitar for everything from rehearsal warm-ups to late night jamming with tracks. They can also be used for stage performances without the fear of feedback because there isn’t a sound hole to produce those resonant frequencies … making them the ultimate loud guitars too!

Pairing It with Helix

The Yamaha SILENT Guitar technology is proven and well established, but how does it pair with the new modeling technologies of the Line 6 Helix® guitar processor, for example, and how do you create a classic nylon string tone for studio and stage?

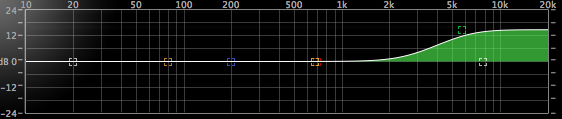

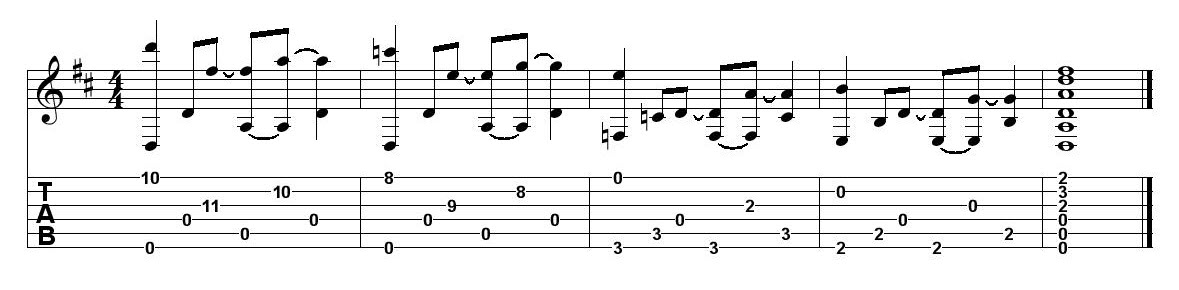

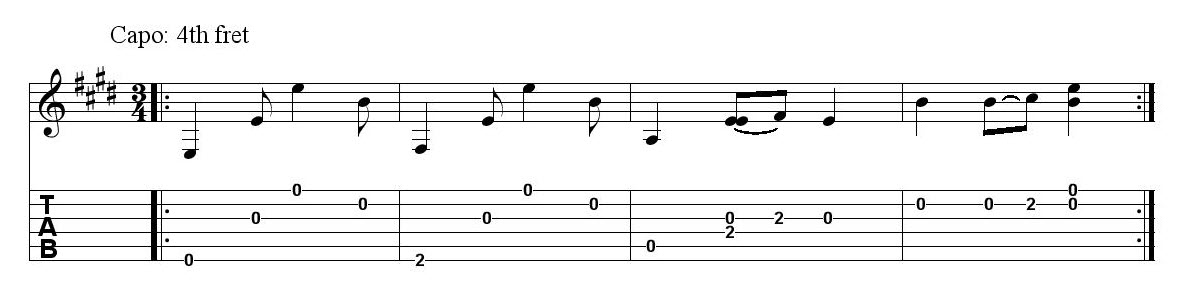

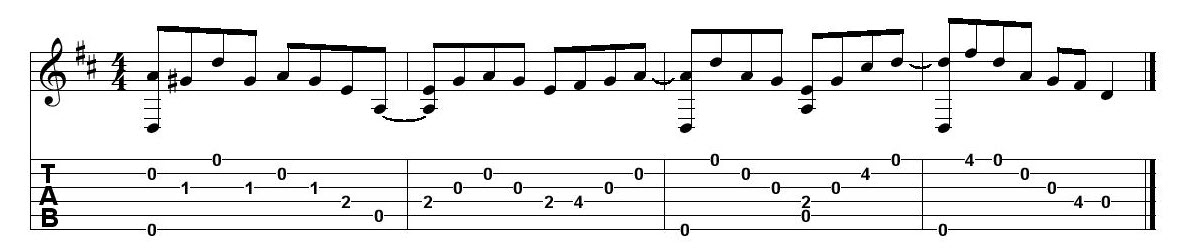

My first instinct is to consider the instrument and its properties in order to determine what the signal chain needs to be to produce a great sound. In the case of the track shown in the video at the end of this article, I felt that all I needed to add to the already pristine nylon string sound the SILENT Guitar was producing was a little more presence and sustain.

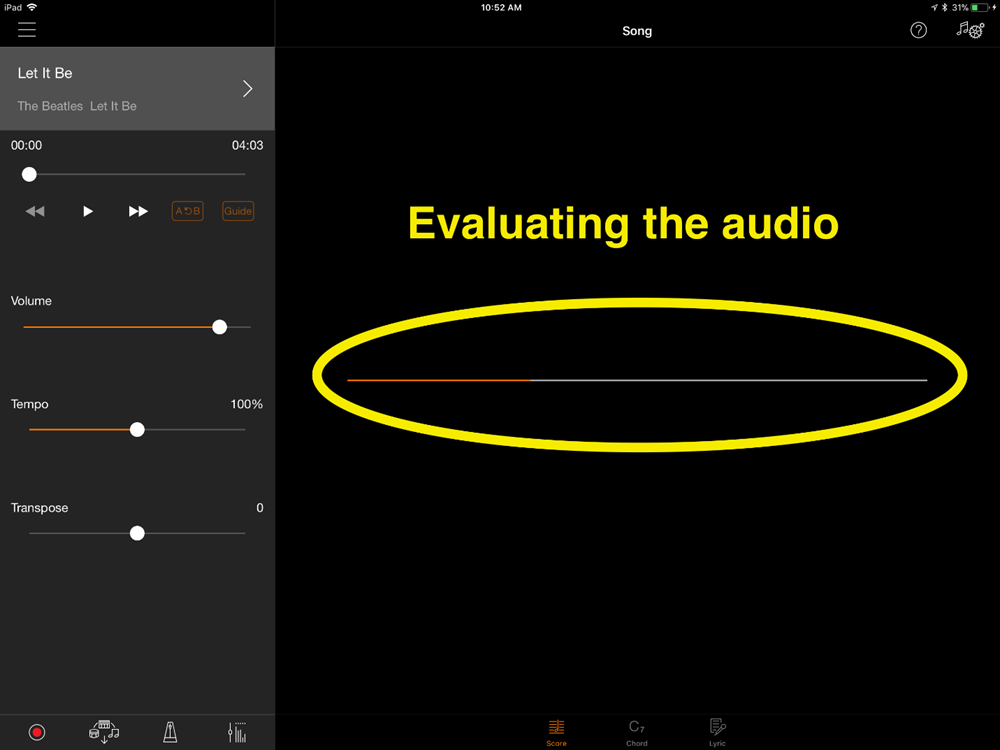

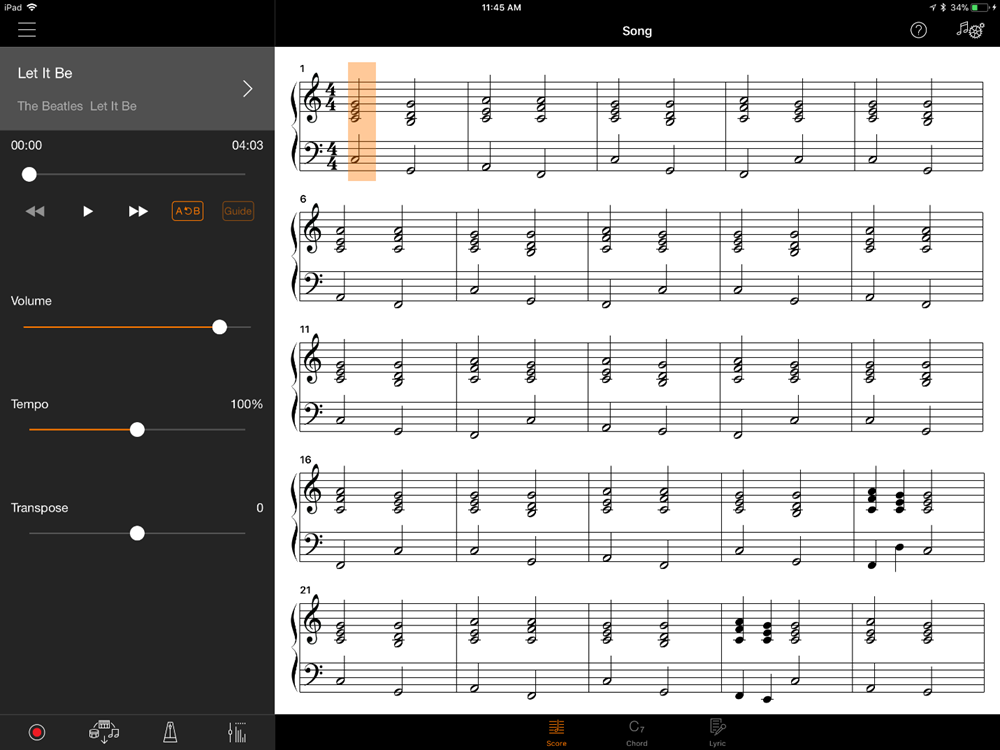

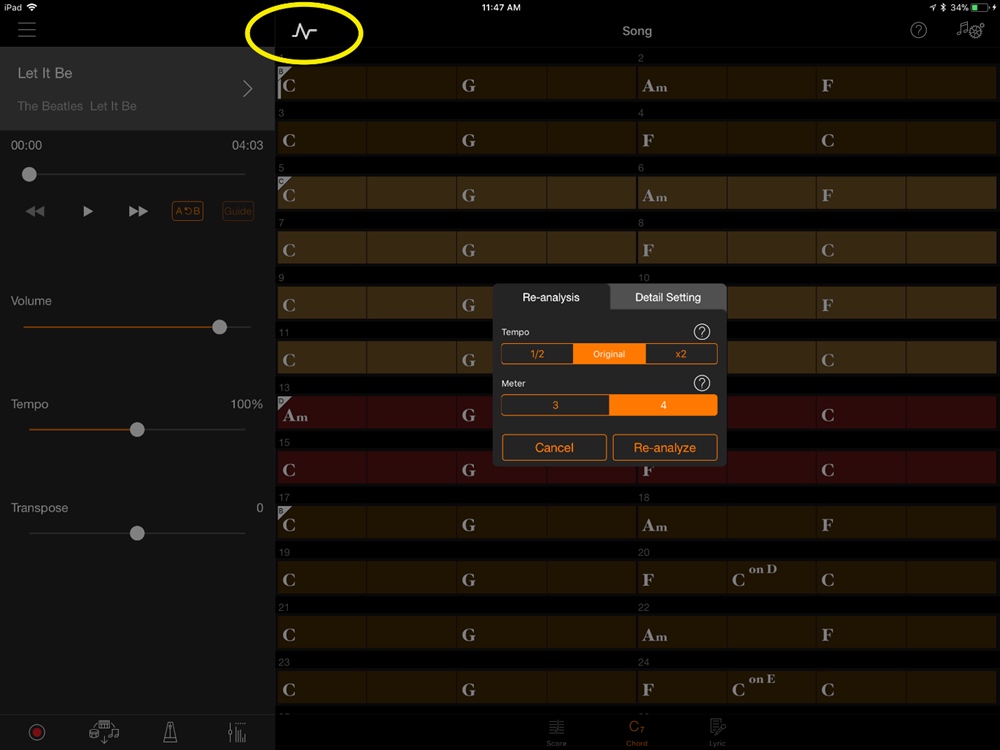

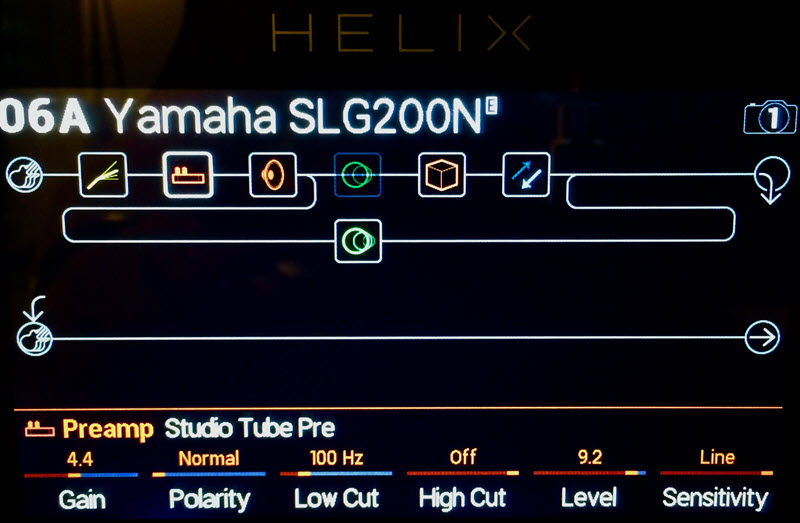

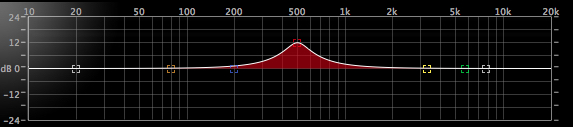

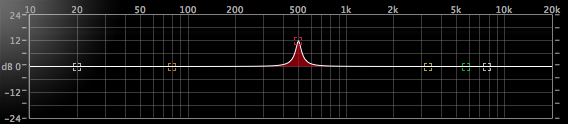

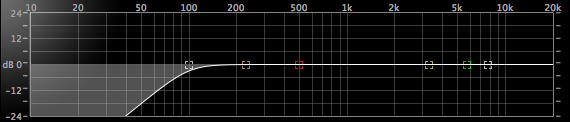

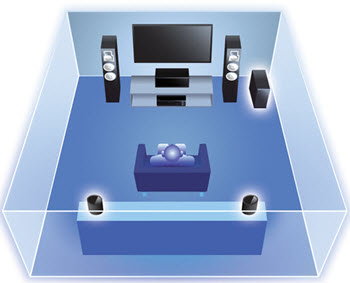

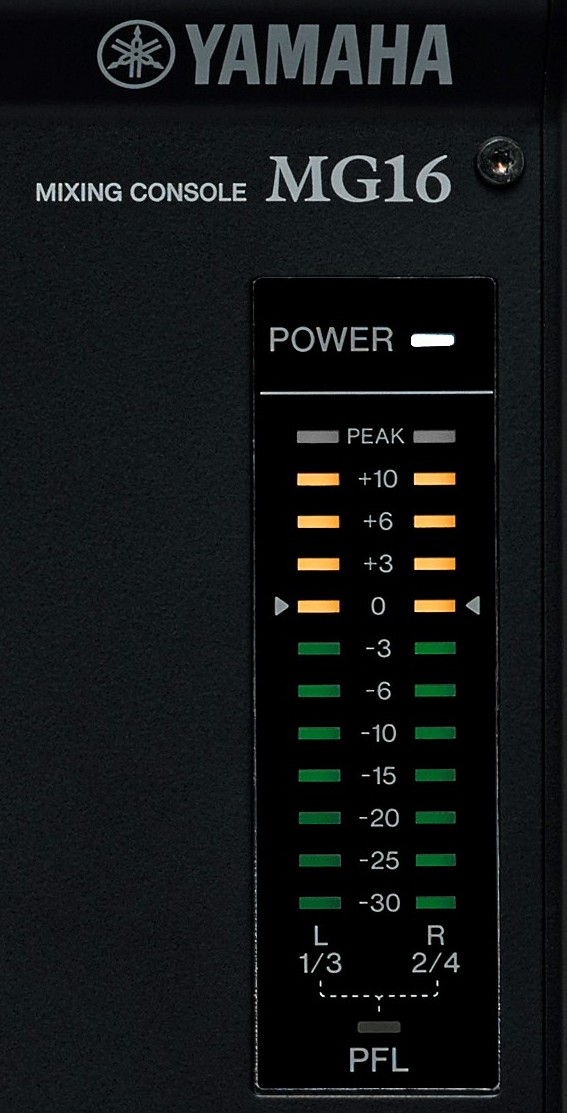

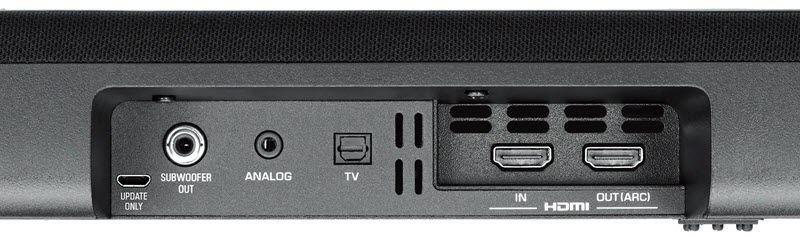

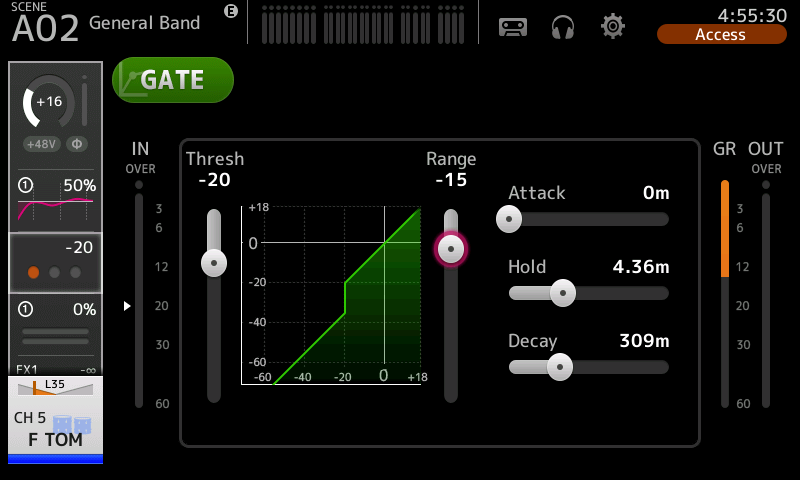

Accordingly, I used the Helix Rack and created a signal chain consisting of Deluxe Compressor (to even out the dynamics and add sustain), followed by the Studio Tube Preamp with a low gain setting (to keep the signal nice and clean). Next came two 2 x 12 cabinet models with Celestion blue and silver speakers, with models of ribbon mics placed 1.5″ from the cone to retain depth in the tone. Then I added a sprinkle of dual delay run in series to soften the effect, with Chamber reverb in parallel added to taste, depending on the guitar part. Here’s a screenshot of the final chain:

(To produce a nylon string finger-style sound, consider using less ambient effects and for the top line melodies add more effect to let the notes sit nicely in the track.) The SLG200N controls were all set “flat” and the blend control placed evenly between piezo and mic modeled sounds. No onboard effects were used. A stereo output from Helix was connected to my computer’s audio interface and from there, to my DAW (Digital Audio Workstation) software.

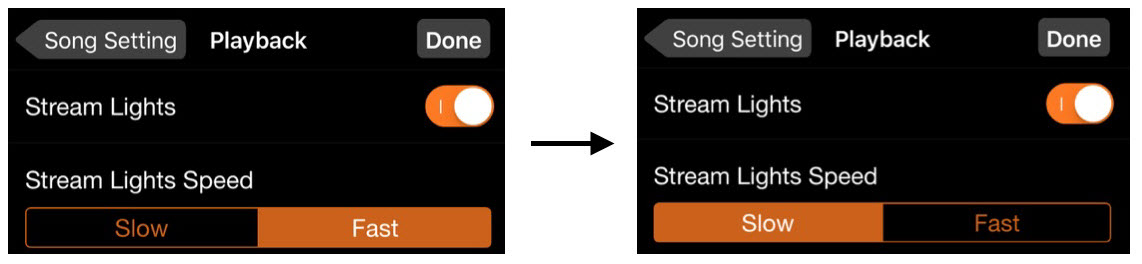

Signal chain routing and rerouting is also super simple. Let’s say you’d like to hear the compressor after the studio preamp instead of in front of the amplifier. Simply select the compressor block, press the “action” button and toggle the effect sideways to a new location.

No need to use a patch bay or move pedals on a pedalboard: Edits can be made in seconds, auditioned and saved to taste.

Going Steel

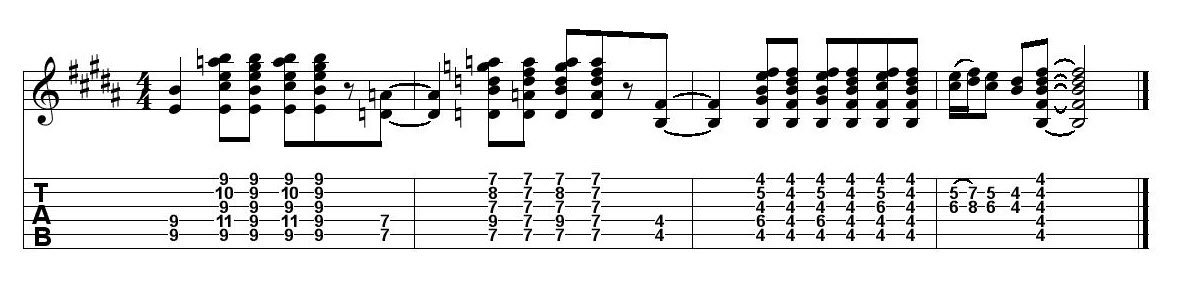

Switching over to the Yamaha SLG200S steel string SILENT Guitar couldn’t be easier. This model offers the same controls and dimensions of the SLG200N, except it uses acoustic steel strings so it inherently sounds like a steel string guitar. (It’s louder than an SLG200N too!)

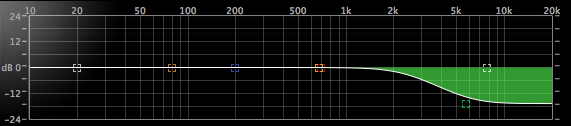

I ran the SLG200S into the same exact Helix guitar patch as the nylon string SLG and tweaked the effects. Chamber reverb was switched to Hall reverb for a smaller, less ambient sound and I dialed in the delays to match the tempo of my track. I was then able to save the edited sound in a new location in Helix as a steel string acoustic guitar template.

The Wrap-Up

Yamaha SILENT Guitars paired with the Line 6 Helix will replicate the same sound consistently due to the technologies producing the sound. Edits can be made, saved to your preferred setlist and the only elements that will fluctuate will be your performance … and that is something we can all appreciate and use creatively for years to come!

The Videos

Here’s my demo of the SLG200N:

And here’s a video of me at a recent Pro Dealer workshop for Yamaha Guitars, where an attendee asked me to add a little overdrive to the sound I was demonstrating on the SLG200S. I leaned down to the Helix floor unit, added a new block in my signal chain for an overdrive and played a gritty delta blues:

Photographs courtesy of the author.

Check out Robbie’s other postings.

Click here for more information about the Yamaha SILENT Guitar.

Click here for more information about the Line 6 Helix.

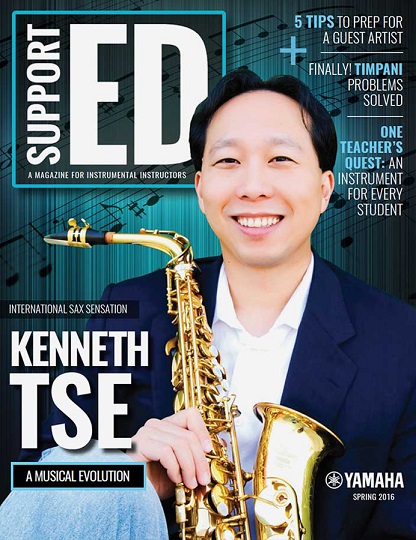

This article originally appeared in the 2017 V1 issue of Yamaha SupportED. To see more back issues, find out about Yamaha resources for music educators, or sign up to be notified when the next issue is available,

This article originally appeared in the 2017 V1 issue of Yamaha SupportED. To see more back issues, find out about Yamaha resources for music educators, or sign up to be notified when the next issue is available,

The relationship between the music directors and principal is key. At Fishers, we have more than 900 students in our music program with six band classes, five orchestras and six choirs during the day as well as many extracurricular ensembles. So it is absolutely vital to share the progress and happenings of our program with the principal. A regular stop by the office builds trust and rapport and opens the door for clear communication with administration.

The relationship between the music directors and principal is key. At Fishers, we have more than 900 students in our music program with six band classes, five orchestras and six choirs during the day as well as many extracurricular ensembles. So it is absolutely vital to share the progress and happenings of our program with the principal. A regular stop by the office builds trust and rapport and opens the door for clear communication with administration. Many schools have a booster organization for the entire performing arts program; others have separate parent groups for band, orchestra and choir. Whatever the case, make sure your program establishes an organization that is student-focused and holds monthly meetings to keep parents connected regarding ensemble happenings.

Many schools have a booster organization for the entire performing arts program; others have separate parent groups for band, orchestra and choir. Whatever the case, make sure your program establishes an organization that is student-focused and holds monthly meetings to keep parents connected regarding ensemble happenings.