Back to School: A Parent’s Guide to Renting and Buying Musical Instruments, Part 2

In Part 1 of this two-part posting, we discussed the benefits of playing a musical instrument and described some common parental concerns; we also talked about the positive impact that having an instrument has on a child’s lifelong appreciation of music. Here in Part 2, we’ll get down to the nitty-gritty and talk about choosing the right instrument, along with the pros and cons of renting versus buying.

Choosing the Right Instrument

In some instances, your child may already know which instrument they’d like to play, and going with their instinct is usually the best course of action, since the motivation to learn will already be there.

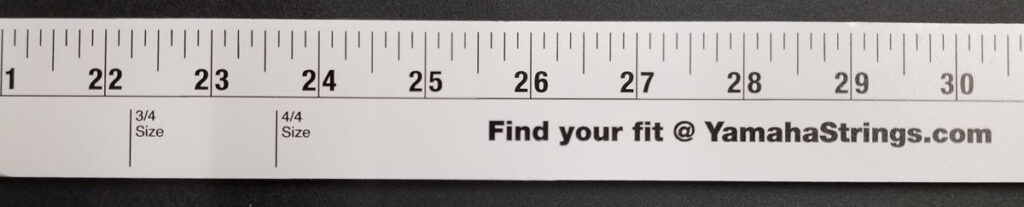

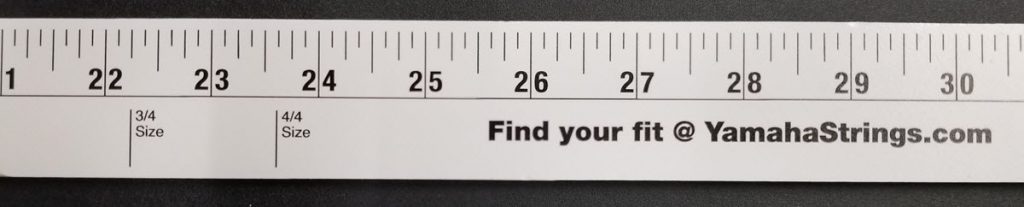

But many times, beginners are undecided: they may have no particular instrument in mind, or they may only know the type of instrument they want to learn (i.e., “I want to play something I can blow into” or “I want to play something with a bow”). In those cases, you should encourage your child to try out several different instruments and see which one they like best. Yamaha offers several online resources to assist with this, including websites that describe various wind and string instruments, along with tips to help in the decision-making process. Your child’s music teacher can also be a great help in making this decision, so don’t be afraid to ask questions: They will likely have a good insight into the most beginner-friendly options and can advise you on instrument-specific considerations such as quality, accessories and proper care. They can also tell you if the instrument under consideration is available in different sizes. For example, Yamaha YVN Model 3 student violins are available in 1/2, 3/4 and 4/4 (full) sizes. If you get one that’s too large or too small for your child, that can impede their progress. Yamaha also makes a device called the “Fit Stick,” which allows a player to be measured without an instrument in their hands. The Fit Stick is simply placed under the chin; when the arm is extended out, the spot where the tips of the fingers land determines the proper instrument size needed. Contact Yamaha to get one free of charge.

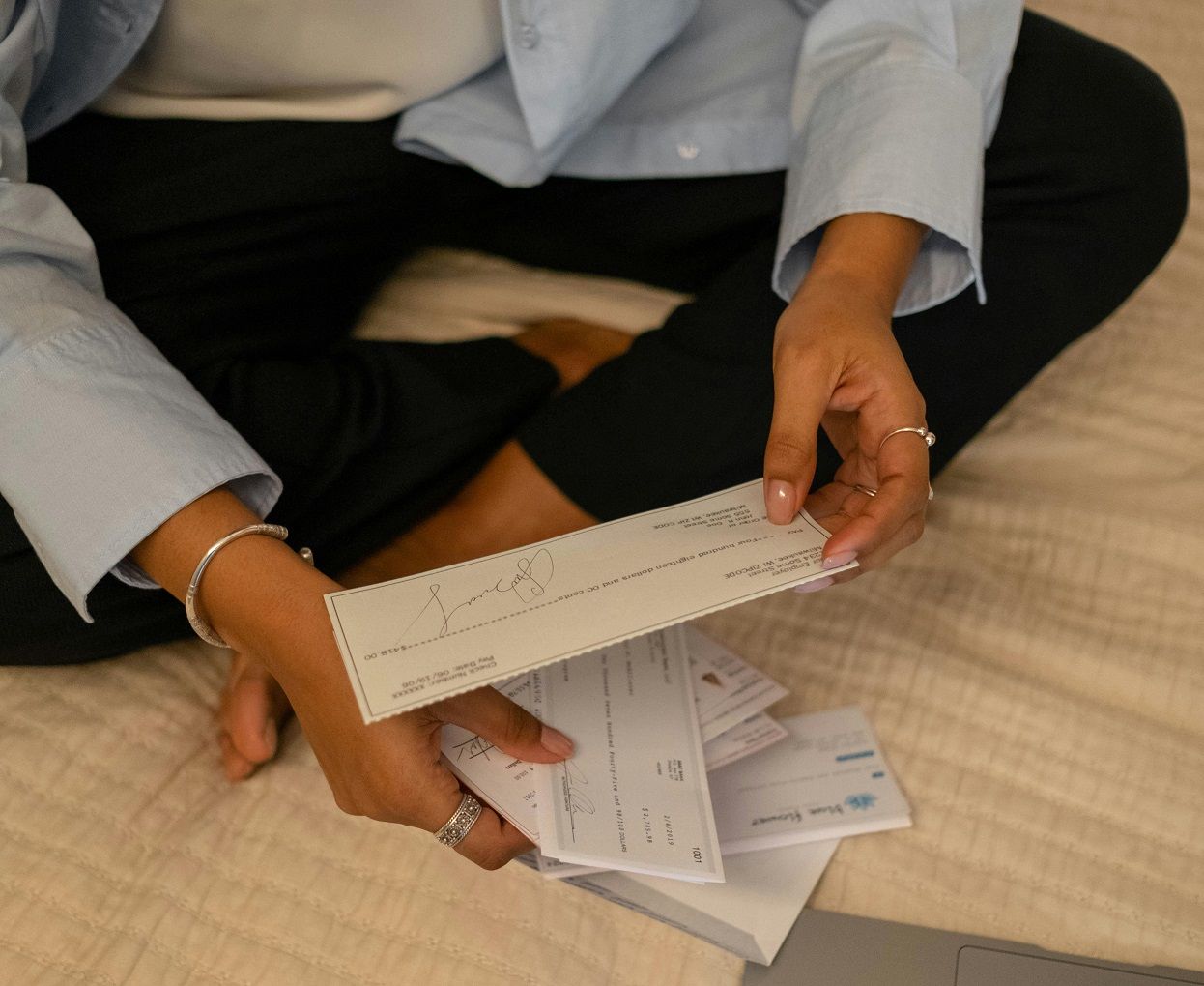

All that said, you may not want to incur the expense of buying numerous instruments for your child to experiment with, and that’s where renting comes in.

Renting an Instrument

Renting can be a smart, flexible choice for many parents of budding musicians. It allows students to experiment with many different instruments at minimal cost to you — a “try before you buy” strategy that can save you money during that exploratory period. “I wanted my kids to play and try different things,” says parent Angela Slawson in the video below, “but it’s expensive to buy everything. Once [my children] picked the ones that they liked, then we bought them the instruments. So we rented to let them kind of explore.”

Most music retailers have rental programs, and your child’s music teacher can refer you to reputable music stores in your area. Many stores even offer a rental night at the start of the school year or the beginning of a new band or orchestra season, and you should try to attend. At these events (which are sometimes held in schools too), students can try out different instruments, and parents can learn about rental costs and options. A music store representative will be on hand to showcase instruments, answer questions and guide families through the rental process. Rental nights may also include presentations about the school’s band and orchestra program, along with opportunities to meet the band and orchestra directors. Sometimes there are even musical performances, making it both an entertaining and informative evening out.

Another major benefit to renting versus buying is that the supplier takes on the responsibility of maintaining and repairing the instrument, at no cost to you. Many non-musicians are unaware of the fact that all musical instruments require regular care to maintain their playability. For example, brass instruments such as trumpet, trombone and tuba need regular cleaning and swabbing, and while the tone holes of most woodwind instruments are covered by pads, some clarinet and oboe tone holes are instead covered by the fingertips of the musician, so they need to be cleaned regularly too. String instruments such as violin, viola, cello, upright bass and acoustic guitar are all made of wood and so are particularly sensitive to temperature and humidity changes, and may need special care during the winter and summer seasons, especially if you live in cold or humid environments. Most people know that acoustic pianos need to be regularly tuned and their keys cleaned periodically, but even guitars, drums, timpani and mallet percussion instruments such as marimbas, vibraphones and xylophones need regular care. These maintenance tasks can sometimes be performed easily at home, but if the instrument has been damaged, you’ll require the services of a trained luthier.

Buying an Instrument

Once your child has decided on which instrument they want to play, buying becomes a strong option, for numerous reasons.

The first is cost: The obvious advantage to buying is that it’s a one-time expense versus a recurring one. Resale value also factors in here, in case your child ever decides to move on to a different instrument or abandon their musical journey (hopefully not!). This is where purchasing a quality instrument — one that suits the player’s needs and level — becomes extremely important, because those are the instruments that last the longest and fetch the highest prices when resold. “I wanted to make sure we got [my children] something good, a quality instrument that will last because it’s an investment,” says Angela Slawson.

How can you determine quality? Your child’s music teacher and your local music store can provide advice and guidance, along with tips as to what to look for in a particular instrument. Yamaha offers a wide range of quality instrument and accessories for musicians at all levels, and our standard models are recommended by many educators for beginning band and orchestra students. What’s more, as your child’s skills grow, Yamaha has the products to help them continue their musical progress.

Quality instruments are not only easier to play, they also sound better. This is an important motivational factor for your child to want to continue learning and growing as a musician. There are few things more frustrating for a beginning music student than having to wrestle with an instrument that’s difficult to play and sounds bad too!

Finally, having a musical instrument they can call their own will give your child a sense of pride. “Once [my children] picked [what they wanted to play], we chose to buy the instrument because it was then their own,” Angela says. “There was a pride associated with, yeah, this is now mine. And I get to play with it whenever I want and however I want. It’s kind of music their way.”

When a child gets an instrument of their own, they will become motivated to care for the instrument themselves, which in turn will stimulate their desire to get better at playing it. And the better they get, the more satisfaction they will get from making music — it’s a circle of accomplishment that spirals upward.

So rejoice when your child announces that they want to learn to play a musical instrument, or come home from school with that note inviting them to join or audition for band or orchestra. View it as the start of a wonderful and fulfilling journey … and know that the process doesn’t have to be overwhelming!

Be sure to check out the Yamaha Parent Resources website.

You Don’t Owe Social Media Anything

I guess their kids are just… better than mine? That’s the thought I had at 11:42 p.m. as I scrolled through Instagram when I should have been sleeping. The post was from a band director I didn’t know. I marveled (and seethed) at the perfectly angled photos of a perfect-looking rehearsal. Kids smiling. Neatly arranged chairs. Some caption about “grateful hearts and hard work paying off.” It had 217 likes.

Meanwhile, my last rehearsal ended with a kid getting their thumb stuck in their third valve slide ring. No photos. No hashtags. Definitely no gratitude in sight.

For a while, I let myself spiral. Maybe their band is just better. Maybe they work harder. Maybe I’m just not cut out for this.

I’ve had to remind myself of this more than once: Social media visibility and real-life value are not the same thing. Not even close.

I knew that the band director’s post didn’t show the full story. Mine wouldn’t have either.

Stop Measuring Your Worth by What Others Post

You already know that Instagram and TikTok aren’t real life. But for some reason, teaching makes us forget that.

Especially when you’re new. During those first few years, everything feels like a competition you didn’t even know you signed up for.

Who’s got the bigger band? Who’s pulling off the harder music? Whose kids are wearing the snazziest uniforms or posing with the cleanest downbeats?

And social media pours gasoline on that fire.

I remember sitting in a department meeting my second year, wondering if I should be doing more — more posts, more updates, more … something. A colleague said, “Your program isn’t real unless people can see it.” I wrote that down in my notebook like it was gospel. I believed it for a long time.

But it’s not true. Or at least, it’s only a little true.

Your program is real every time you unlock the door and say hi to the first kid who walks through it. Whether anyone sees it or not.

Those posts you’re comparing yourself to? They don’t show the full picture. They don’t show the 17 reminders it took to get kids in the right shirts. They don’t show the broken reeds, the forgotten mallets, the student crying in the hallway because of something that has nothing to do with band but still showed up in your room. Even if a post shows a band that’s a well-oiled machine, it doesn’t show the 10 to 15 years it took to get to that “overnight success.”

Social media doesn’t show you, sitting alone after school, staring at a schedule and wondering how you’re going to make it all fit.

You’re comparing your worst day to someone else’s highlight reel. It’s not fair, and it’s not helpful.

Also, half of those highlight reels are scheduled weeks in advance. I’ve done it. I’ve posted a glowing photo of my band right after a rehearsal where I wanted to hurl a music stand through the window (our room is on the second floor, by the way).

We’re all faking it a little. Remember that.

Social Media Is a Tool, Not a Requirement

Here’s a secret that took me longer than I’d like to admit to figure out: You don’t have to be on social media to be a good teacher.

Yes, it can help with recruitment. Yes, it can help with advocacy. But it’s not mandatory for your program to survive, and it’s definitely not mandatory for you to survive.

There was a stretch where I posted everything. Concert photos, pep band hype, fundraisers, kids moving stands. I was chasing “engagement” without really knowing why. Likes went up. Followers went up. My stress went up.

I noticed I was spending more time crafting captions than crafting lessons. I cared more about whether the lighting was good on a picture of my trumpets than whether they were ready for the concert.

That’s when I realized: This isn’t for me. This isn’t for my kids. This is for … who, exactly? Other directors? The admin scrolling through at night?

My students didn’t need proof that we were doing good work. They needed me to be present enough to actually do the work with them.

Now? I post when it feels useful. When there’s an alumni update someone might care about, or a concert announcement that helps get butts in seats. Not because I owe anyone proof that we’re trying hard.

If you love posting and it lights you up? Great. Keep going. If it drains you, distracts you or makes you question your worth? Opt out.

Your program won’t vanish. Your kids won’t stop learning. You’re allowed to be a teacher, not a content creator.

Focus on Your Actual Students, Not Imaginary Audiences

This sounds obvious, but it’s worth saying out loud: Your job is not to impress strangers on the internet. In fact, the majority of these people will never even see your group live and only watch about 15 seconds of the Facebook livestream.

Your job is to show up for the kids who are in your room. The real ones.

The ones who forget their music stands. The ones who play too loud. The ones who ask you every Friday if there’s rehearsal even though they’re already in the room.

They don’t care how many likes you get. They care if you notice them. If you listen to them. If you show up, over and over, even when you’re tired or frustrated or convinced you’re the worst teacher in the building.

I had a clarinet player once — sweet kid, always late, never had a pencil, couldn’t count to save their life. Every week felt like starting over. But then, senior year, they came to me after the final concert and said, “Thanks for not giving up on me. Band’s the only place I felt like I wasn’t screwing up all the time.”

That didn’t happen because of a Facebook post. That happened because I kept showing up in the room.

You can build a solid program and change kids’ lives — and no one on the internet ever has to know. (Pssst — yes, it really does happen if you don’t tell anyone on the internet!)

The people who matter will notice.

Your Value Isn’t Tied to Visibility

It’s easy to forget this when everyone’s busy “building their brand.” But teaching isn’t content creation. What matters isn’t how many people follow you.

It’s measured in the kid who finally nails that scale. The senior who says thank you. The parent who tears up after the concert. The alumni who comes back to visit after college and tells you that your class still helps them get through hard days.

None of that shows up in your analytics. But that’s the stuff that sticks.

Remember, there are teachers changing lives in classrooms who no one ever sees. They are quietly and consistently doing their job without anyone clapping for it. You can be one of them.

The teachers who make the biggest difference usually aren’t the ones posting the most. They’re the ones so busy doing the work that they don’t have time to curate it.

If that’s you? You’re not behind. You’re exactly where you should be.

And if you really need the exposure? Get an approved parent to do this for you (just check with your district first). This saves so much time and energy that you can put back into your program in the way that only you can do.

You Don’t Owe Proof of Your Good Work

You don’t need to prove your worth with posts. You don’t need to keep up with anyone else’s highlight reel.

The work you’re doing — the frustrating, imperfect, joyful, exhausting work — is already enough.

Keep showing up. Keep teaching. The right people are paying attention.

And they don’t need hashtags to find you.

#IfWeHadADollarForEveryLikeWeCouldStopFundraisingSoMuch

Why Patience Wins Over Panic

“Do you even want to be here right now?” I asked the class. I didn’t yell it. I didn’t even say it in a particularly mean tone. It just slipped out — half honest question, half exasperated sigh — in the middle of a rehearsal where half the band wasn’t playing, a quarter was looking at their phones, and the rest were asking if we could “just skip this part.”

Most of the students shrugged. A few offered weak apologies. A lot of them didn’t even look up. Standing there, baton in hand, I felt that familiar pit in my stomach and thought: Why am I doing this?

This was during my third year of teaching, which might be harder than your first two years. In Year One, everything’s chaotic and you’re forgiven for it. During Year Two, you have some experience, so this should be easier, right? By Year Three, you’re supposed to have figured some things out. Spoiler: You haven’t.

They’re Not Starting Where You Are

If the kids weren’t engaged, I must be boring. If they weren’t practicing, I must have picked the wrong music. If they weren’t motivated, maybe I wasn’t inspiring enough.

Cue the spiral: Why am I doing this? I should quit before they realize I don’t belong here.

But the truth is a lot simpler (and less about me): Kids don’t arrive pre-motivated. Not for scale sheets. Not for breathing exercises. Not for your favorite John Mackey piece. Not even for a trip to Disney, if you’re offering one.

Kids arrive tired, distracted, overwhelmed, insecure, awkward, hormonal or all the above. They’re kids. That’s their job.

It’s our job to model what it looks like to care — over and over — until they catch on. For years, I kept waiting for some magical moment where a kid would walk in and say, “Wow, I just realized how important this is, and I’m ready to give 110%!” I know this won’t come as a shock, but I’m still waiting.

What I see now is that they’re watching me more than I realize. They watch and see how I show up on the boring days. How I react when things fall apart. How I treat the kid who’s not getting it. That’s what builds trust. That’s what keeps them coming back, even if they’re not showing it yet.

Set Clear Expectations and Repeat Them Without Apology

Early on, I thought I had to justify every rule. Like: “No phones because … research … cognitive load … respect … blah blah blah.”

Now? I simply say, “No phones. Put them away.”

Same with posture. Same with playing position. Same with rehearsal routines.

I used to think if I was clear once, they’d remember forever. I thought the problem was that my instructions weren’t inspiring enough. Nope. The problem was repetition — or my lack of it.

Think about it: I remind my own kids to brush their teeth every day, and they’ve been alive for over a decade. Why wouldn’t I need to remind a 9th grader to sit up and play with the right hand position?

One year, I made a laminated checklist for every section’s rehearsal responsibilities:

- Chairs straight

- Music in order

- Instruments out (not halfway out, not “almost out”)

- Phones away

It lived on the whiteboard. They rolled their eyes at it. I kept pointing to it. By October, it was working. Not because of the sign — because of the consistency.

You don’t need to turn your expectations into a tech manual. You just need to say it. Then say it again. And again. Not sarcastically. Not with resentment. Just like it’s normal. Because it is normal.

Showing up on time, getting your stuff out, actually trying — those are habits, not personality traits. And like any habit, they need reminders.

Celebrate Progress Louder Than Failure

You can’t guilt kids into caring. Not long term. I’ve tried. It just makes everyone feel bad and nothing gets better.

What works? Catching progress and calling it out like it matters. Because it does.

The first time my low brass section nailed an entrance they’d been late on for weeks, I stopped rehearsal and said, “Did you hear that? That’s what I’m talking about.”

They smiled. Not big, not dramatic. But enough. Enough to tell me: Okay. This matters.

Another time, I noticed that a clarinet player — one of my quiet, never-makes-eye-contact kids — had finally written in a tricky fingering after struggling with it for months. I didn’t make a big show. I just walked over after rehearsal and said, “Good job fixing that spot. That’s how you get better.”

Three weeks later? That same kid is marking their music more and helping younger players. Not because of my compliment. Because she started believing she could figure things out.

Kids won’t always tell you they care. But they’re watching for evidence that you notice when things get better. They need to feel like getting better matters to someone.

Side note: This is just as true for your seniors as it is for your 6th graders. They’re all looking for proof they’re moving in the right direction.

Don’t Confuse Apathy with Confusion or Insecurity

“I don’t care” is often code for “I don’t know how” or “I’m afraid I’ll look dumb if I try.”

I once had a percussionist who never seemed to engage. Always late, always zoning out, always with an excuse. I kept thinking, he doesn’t care. Turns out, he didn’t know how to read rhythms beyond quarter notes. He was terrified to admit it because he’d somehow faked his way through middle school band.

The minute we started breaking things down — literally writing rhythms on the board, clapping them together, building back from the ground up — his “I don’t care” started turning into “can we try that again?”

I’ve seen it too many times — kids checking out, not because they’re lazy but because they’re lost. They missed something early on — a fingering, a rhythm, a concept — and now they’re too embarrassed to ask. So, they sit back. They clown around. They roll their eyes.

And it’s easy to get frustrated. But if you pause and ask — really ask — “What’s holding you back right now?” you’ll often find it’s not attitude. It’s fear.

Try this trick: Watch who suddenly perks up when you model something slowly, or who lights up when you say, “I used to struggle with this part, too.” That’s where the work begins.

Patience Isn’t Weak. It’s Leadership.

There’s a version of the story where I blew up at that rehearsal described at the beginning of this article. Where I lectured, punished and stormed out. I actually lived that version, and I’m here to tell you that it doesn’t work.

What works is staying steady. Saying the same expectations calmly. Noticing small wins. Asking better questions. Modeling what care looks like when no one else is giving it back yet.

This isn’t easy. I’ve gone home plenty of days thinking: Maybe I’m just bad at this. I’ve sat in my car wondering if today was the day a kid would finally decide that band was stupid because I didn’t handle it well.

But here’s what I’ve seen: The teachers who last and the music programs that thrive aren’t the ones with the biggest trophies or the flashiest shows. They’re the ones where patience is baked into the culture. Where kids are allowed to grow up a little slower. Where failure isn’t met with shame but with, “Okay, let’s try again.”

Patience isn’t weakness — it’s leadership. It’s knowing that these moments — the phones-out, horns-down, eyes-glazed-over moments — are temporary.

What’s permanent is the example you’re setting. And that example? It’s starting to stick. Even if you can’t see it yet.

10 Habits That Make Teaching Harder Than It Needs to Be

I thought I was just being a “good teacher.”

During my first year, I stayed at school until 6:00 p.m. every night. I ate lunch standing up (if at all). I answered emails like a 24/7 help desk. I said yes to every opportunity, even the ones I hated. At one point, I had a student ask if I lived at the school.

Looking back, I wasn’t being dedicated. I was afraid. Afraid to be seen as lazy. Afraid someone might think I wasn’t doing enough. Afraid I’d fail if I didn’t do everything all the time.

The lesson? The habits we told ourselves were just part of paying dues are often the ones burning us out the fastest. Also, isn’t paying our dues showing up and doing the work? Advice is great, but if someone isn’t signing your paychecks or a trusted mentor, don’t take the advice as gospel.

I’m not usually a fan of the saying “every time you point a finger, four more point back at you,” but …

If you’re feeling overwhelmed, isolated or like you’re somehow always behind — it might not be your kids, your admin or your schedule. It might be the habits you’ve picked up trying to prove you care.

Let’s talk about a few of them.

1. Skipping Lunch Isn’t a Sign of Distinction

You’re not more dedicated because you worked through lunch. You’re just hungrier. And crankier.

I used to think grabbing a handful of pretzels between classes counted as lunch. One day I made the mistake of sitting down during 6th period to write some drill changes and almost fell asleep at my desk. I wasn’t tired because the kids were exhausting — I was tired because I hadn’t eaten a real meal since 6:30 a.m. And explaining the imprint of a Snyder’s pretzel on your forehead is a difficult and embarrassing conversation to have.

Fun fact: Your body doesn’t care how noble your reasons are. No food = no energy. No energy = bad decisions. Like agreeing to run a pep band on Saturday again even though you swore last time was the last time.

Now, I eat lunch like it’s my job. Because honestly, it kind of is. Your brain needs fuel. Your patience needs fuel. Your sense of humor definitely needs fuel.

Even if it’s just five minutes alone in your office with a sandwich, it’s better than nothing.

2. Taking Work Home Every Night Isn’t Normal

I used to haul my laptop home every night. I thought if I just stayed ahead of emails, ahead of paperwork, ahead of grading … I’d be ahead.

Plot twist: It never worked.

Instead, I felt bitter. I’d see other people relaxing, going out to dinner, watching TV and think, “must be nice.” Once I had must be nice in my head, I was getting in too far.

Nobody assigned me that work. I assigned it to myself. I could have left it for tomorrow. I could have said, “Good enough for today.” But I didn’t know how.

One rule that helped: I picked one night a week where I’d allow myself to bring something home. Tuesdays, usually, because Mondays were survival mode and Wednesdays already felt like “almost the weekend” in my brain. That simple limit made me more focused during the day because I knew I wasn’t just kicking the can to 9:00 p.m. on my couch.

Most things can wait. Really. Seriously. Just try it.

3. Answering Emails at 10 p.m. Makes Things Worse, Not Better

At some point in my early years of teaching, I convinced myself that fast email replies meant I was being professional. So, I answered emails in the evenings, on weekends, during dinner, even at a wedding reception once. Don’t ever do that, and I won’t admit whether it was my own wedding.

All it did was teach people that I was always available — and then I’d get quietly annoyed when they expected me to be.

I finally stopped doing this when I realized that I was feeling physically anxious every time my phone buzzed after 7:00 p.m. Like, What now? What do they need from me now?

That’s not a great way to live.

Now, I set a cutoff. After 5:00 p.m.? Unless it’s an actual emergency (and 99% of the time it isn’t), it waits until morning.

Side benefit: You sleep better. Your brain learns that it’s allowed to shut down.

4. Comparing Yourself to Everyone Online Is Wrecking Your Confidence

There’s always going to be some school online with fancier uniforms, bigger budgets, flashier shows. There’s always going to be some teacher posting about their 47 superior ratings and their students who practice three hours a day because they want to.

You know what they don’t post? The burnout. The bad days. The emails from admin saying, “Why is Johnny failing math when he’s in your band?”

It took me too long to figure this out: You can be inspired by other programs without letting them make you feel small. The measure of success isn’t what you post on Instagram. It’s whether your kids feel safe, challenged and seen.

And some years, honestly, the win is just getting all the kids to the concert in the right uniform.

5. Believing Exhaustion Is Inevitable Makes You Stay Exhausted

Exhaustion isn’t a personality trait. It’s just exhaustion. “Oh, you’re tired? Yeah, me too. Twelve-hour day. Rehearsal. Paperwork. Didn’t even eat dinner yet.”

Good…for…you? No!

It felt like a weird badge of honor — like I was proving how hard I worked by how miserable and drained I was. At some point, you must come to realize that exhaustion isn’t a requirement of the job.

Sure, some weeks are going to run you ragged. But if every week feels like survival mode, something’s out of balance.

I started asking myself: Is this exhaustion necessary? Or am I creating it by refusing to set limits? Most of the time, it was the latter.

This job isn’t supposed to be about who’s the most exhausted. It’s not about whose group is the biggest or best.

6. Saying Yes to Everything Makes You Reset Everything

It took me three years to learn this: Every “yes” costs something.

Yes to running the talent show? That’s one less night with your family. Yes to chaperoning the dance? That’s energy you won’t have for your own students the next day. Yes to judging solo and ensemble on your only free Saturday? That’s one less day to recover.

At first, I said yes because I thought I was supposed to. That’s how you build good will, right? That’s how to be a team player.

Pretty soon, I noticed I was dreading things I used to enjoy. Even music. Even teaching.

The thing I looked forward to most were silent car rides because that was the only time I had to reset, regroup and recharge.

Something had to change.

You’re allowed to say no. You’re allowed to guard your time like it’s something precious because it is.

7. Refusing Help Doesn’t Make You Stronger

I was terrible at this.

- People would offer: “Want me to cover your study hall so you can prep?” I would smile and say, “No, I’m fine.”

- “You need help loading the truck for the parade?” “No, I’ve got it.”

Half the time I didn’t have it. I wasn’t fine. I was just too stubborn or embarrassed to admit that I needed help.

Ultimately, people want to help. They want to share resources, split duties, trade ideas. Saying yes doesn’t make you weak. It makes you part of a community.

Now when someone offers, I say yes. Not every time, but enough times to remind myself that I don’t have to do this alone. (Unless it’s that one colleague that never stops talking…)

8. Making Everything About the Job Will Leave You With Nothing Else

I didn’t notice how bad things were until I realized that I didn’t have any hobbies anymore. No books for fun. No movies unless I was falling asleep to them. No conversations that didn’t circle back to work. Just family members that said, “all you talk about is band.”

It happens slowly. You skip one hangout because you’re behind on grading. You cancel one weekend because of a contest. Pretty soon, your whole world is music education.

And when school gets stressful — which it will — there’s nowhere else for your brain to go.

Now I have non-music things I protect. Dumb video games. TV shows. Walking the dog. Small stuff that makes me feel like a person, not just a teacher.

9. Thinking It’ll Get Easier “Once You Figure It Out” Keeps You Stuck

You’ll never figure it all out. Not really.

You will get better at managing the chaos. You learn where to cut corners, where to push, where to let go. But the job evolves. The kids change. The expectations shift.

If you’re waiting for some magical year where everything clicks and stays clicked? You’ll be waiting forever.

What helps is building routines that make this version of teaching sustainable. What helps is accepting that some days you’ll still feel behind — and that’s OK.

10. Believing You Have to Do It Alone Is the Fastest Way to Burn Out

Early on, I thought needing support made me less competent. That if I really had what it takes, I wouldn’t need advice or encouragement.

That’s nonsense.

The teachers who last aren’t the ones who tough it out alone. They’re the ones who build networks. Friends who get it. Colleagues who share resources. Mentors who remind you, “This is normal. You’re not failing. It’s just hard right now.”

I have people I text when I’m ready to quit. I have people who make me laugh when nothing else works. I have people who remind me why I started.

Find people who get it. Hang on to them.

The Habits Are Yours to Change

None of these habits make you a “bad teacher.” They make you human, but they also make you tired.

The good news is that you get to choose what you carry forward. You get to build a version of this job that you can actually live with.

Start small. Eat lunch. Answer the email tomorrow. Go home on time.

It adds up. And so do you.

Work Smarter Especially When You’re Burned Out

I caught myself thinking: I guess I’ll just stay late again — as I stared down a to-do list that had somehow grown overnight. Paperwork, chair tests, emails, locker assignments, some random form for something I didn’t understand … and it was only Monday. The weeds in my lawn and my to-do list seem to grow at the same rate. Adding insult to injury, my neighbors are starting to get upset about my lawn because I’m always at work.

The absurd part? Half of the tasks on the list didn’t need to be done right now. Or ever, if I’m being honest. I had fallen into the trap of doing everything just because it landed on my desk.

That’s how burnout sneaks up on you. It’s rarely the big stuff. It’s actually the small, pointless tasks that we convince ourselves are urgent.

Eventually, I asked myself: What if I just … didn’t?

Turns out, a lot of it didn’t matter. And the things that did matter? Well, they improved when I wasn’t drowning.

Here’s how I learned to work smarter, not harder — and definitely not later.

Streamline Your Routines Ruthlessly

Teachers love routines. Until they don’t. At some point, I realized my “systems” were just elaborate ways of wasting my time. For example:

- Monday morning inventory checks — no one noticed when I stopped doing them.

- Color-coded seating charts updated weekly — I was the only person who cared about this.

- Hand-written practice logs — half were forged, the other half didn’t improve anyone’s playing. The only good thing that came out of these logs was that they helped form a bond between parent and student as they collectively tried to pull one over on the teacher.

I finally sat down and asked myself: Do these things actually help my students? The answer was embarrassingly clear: Not really.

So, I started cutting.

Now my attendance system is a sticky note. My announcements live on a whiteboard. My lesson planning is a bullet list, not a Stephen King novel. I check instruments when something sounds weird, not on a schedule designed by a past version of me who clearly hated free time.

The mental load lightened immediately.

Your students don’t need elaborate — they need consistency. Your admin doesn’t need pretty — they need verification of submissions. Your mental health doesn’t need extra — it needs protection.

So, stop adding steps where none are needed. Yes, this includes the binder covers you downloaded off Pinterest during a planning spiral and updating your bulletin boards every season. Nobody notices your bulletin board but you, so let it go.

There’s nothing wrong with being “extra” as long as you have extra time. Chances are if you’re reading this, you don’t.

Focus on What Moves Your Students Forward

You’re never going to finish all the things. That’s not cynicism; it’s math. One of my worst habits early in my career was mistaking “done” for “effective.” I’d leave school with every task checked off but then realized that I hadn’t taught anything well that day.

So, I made a new checklist:

- Do students sound better?

- Do students understand what we’re doing?

- Are students more confident walking out than walking in?

If the boxes were checked, great. If not, I knew where I had to put my energy.

Here’s a real example: Last spring, I planned an intricate rhythm reading unit with packets and stations and assessments. Halfway through, I realized my kids just needed more time counting and clapping together. I ditched the packets, grabbed a whiteboard and we spent two weeks doing rhythm drills as a class. Guess what? They improved faster. No paperwork required.

Sometimes the simplest thing is the most effective — but it’s hard to see that when you’re buried under “busy.”

Stop Confusing Busy with Effective

I used to wear “busy” like a badge. Running from task to task, juggling paperwork, answering emails at night — all proof that I was working hard. Thank goodness, I kept an extra stick of deodorant at school.

The problem? My students weren’t learning faster. My concerts weren’t improving. I was just tired.

I remember one particularly brutal week where I stayed late at school every day, thinking I was being a hero. By Friday, I had a clean office, updated spreadsheets and zero energy for rehearsal. That’s when it hit me: Busy isn’t helping anyone if I’m too drained to teach.

Now, I protect my time like it’s oxygen.

- I don’t answer emails after school unless it’s urgent (and I’m slowly moving toward not even checking email).

- I batch my admin work so it doesn’t bleed into teaching time.

- I say no to extra duties unless there’s a really good reason. (Hint: “It’s tradition” is not a good reason.)

Here’s the difference: I leave work with energy left for my family, my hobbies and occasionally just sitting on the couch doing nothing. That makes me a better teacher the next day.

Busy isn’t the goal. Better is. (And better usually looks way less impressive on paper.)

Also, just to be clear — you don’t get extra points for exhaustion. You don’t get a gold star for being the last car in the parking lot. You get bags under your eyes and you get burned out. That’s it.

Automate What You Can, Delegate What You Should

I fought this one for years. I thought using templates made me lazy. I thought asking for help made me look incompetent. I thought doing everything myself proved I was dedicated. Spoiler: None of that is true.

Here’s what is true:

- Templates save you time and sanity.

- Delegating helps others grow.

- Automation frees your brain for actual teaching.

Some real-life examples from my classroom:

- My weekly rehearsal plan is a Google Doc I copy and paste from last year, with minor edits.

- My student leaders handle locker assignments and uniform checkouts.

- I use A.I. when appropriate.

None of this makes me a bad teacher. It makes me a teacher with fewer headaches.

The things I used to spend hours fussing over? They still get done. Just faster, and not always by me.

Automation isn’t laziness. It’s survival.

Delegation isn’t weakness. It’s how you make it to June.

And if you’re worried someone will think you’re cutting corners, remember that the people who matter (your students, your family, your future self) will thank you.

Let Go of Things That Don’t Matter Anymore

Some things were important once. Some things were never important but felt urgent. Either way, you don’t have to keep carrying them.

I admit that this was hard for me. I’m a sentimental person. I hold onto traditions, habits and ideas long after they’ve stopped serving me. I kept running sectionals that no one showed up for. I kept assigning theory packets no one learned from. I kept worrying about locker decorations.

Eventually, it hit me: Just because I’ve always done it doesn’t mean I have to keep doing it.

Now, I give myself permission to retire things that aren’t working.

- If a routine feels forced, it’s not helping.

- If an assignment doesn’t lead to growth, it’s not worth assigning.

- If an event drains more energy than it gives back, it’s time to let it go.

Your students won’t remember how busy you looked. They’ll remember how present you were.

Here’s a small but real example: I used to stress over having perfectly typed concert programs, formatted within an inch of their lives. One year, the copier broke the day before the concert. I slapped together something simple, ran it on colored paper, and moved on. Not a single parent complained. The kids played great. That’s what people noticed.

Letting go of the unnecessary doesn’t lower your standards. It raises your focus.

You’re Allowed to Work Differently Now

If you’re feeling burned out, it’s not because you’re weak. It’s because teaching asks too much — and gives you too little time to figure it out.

Working smarter isn’t about productivity hacks. It’s about protecting your energy for what really matters: helping kids, making music, staying human.

You’re allowed to work differently now. Honestly, you probably have to. It doesn’t make you less of a teacher. It just makes you a teacher who lasts.

And trust me — the kids need teachers who last.

Back to School: A Parent’s Guide to Renting and Buying Musical Instruments, Part 1

Your child has just come home from school with a note for you, inviting him or her to join (or audition for) the school’s band or orchestra. Your kid is willing — maybe even enthusiastic — so you give your consent.

Now what?

In this blog posting, we’ll provide you with a guide to the process of getting your child an instrument to play and give you tips for navigating through the journey; in Part 2 of this two-part series, we’ll tell you how to choose the best instrument for your child and describe the advantages and disadvantages of renting versus buying.

Let’s start by talking about the excitement that goes with launching your child on their musical journey.

Benefits of Playing an Instrument

Numerous studies have shown that learning to play a musical instrument at any age is good for you physically, mentally and socially, but it’s especially beneficial to a child’s development. Children who play an instrument do better in school, develop improved language skills, are likely to have more advanced physical coordination and emotional intelligence, and are socially well-balanced. Joining a school music program not only builds lifelong skills but also creates a sense of belonging and community, allowing your child to grow their musical abilities and develop meaningful connections.

So congratulations! You’ve made the right decision. The next step is to help your child choose which instrument to play.

Common Parental Concerns

If you’re thinking this sounds like too daunting a process, you’re not alone, but with a little guidance from your child’s teacher and a reputable music store, it’s a path that’s actually easy to navigate. As parent Angela Slawson says in the video below, “Now that we’ve gone through it, I think back to when we started [our children] in music and all the anxiety I had of not knowing what to do, who to call, how do I get them set up, all of that.… [But] if you’re a future band parent out there, my advice is, let your kids explore. Let them find their voice through music and don’t let the unknown prevent you from finding a music store and asking the questions. And then just know that they come out with more than just learning how to play music.

Fellow parent Prudence Elliott adds, “Also, don’t be afraid to … lean into your music teachers and your local music stores for advice. They have years of knowledge. Also [communicate with] other parents of music students: They are part of your team. They’re going through it with you.”

What Parents Wish They Knew Earlier

We asked both Angela and Prudence what they wished they knew early on in the process and Prudence’s reply was, “The importance of a good, lasting, quality instrument, especially when starting out, [and] that a well-made instrument sounds great, and is definitely something that will last longer.”

“Plus,” Angela added, “how important it is that the instrument doesn’t stand in the way of [your child’s] learning.”

Both parents also wished they had known in advance whether or not their music store had tutors and offered lessons after school hours. “Sometimes [my child’s] music teacher did,” Prudence explains, “but he only had very small blocks open for one-on-one time.”

“I did not know that there are private tutors for instruments like strings,” adds Angela. “It’s common knowledge that there are piano teachers, but I didn’t know that there would be a saxophone tutor or a cello tutor.”

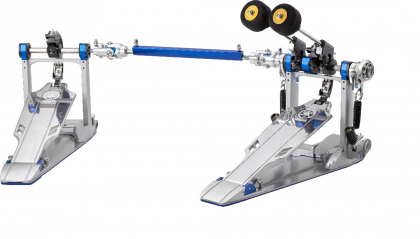

There were also some surprising insights. “My younger [child chose] the viola as his first instrument,” says Angela. “It makes sense that the string quality and the bow matter, but all that I thought about was the case and the instrument. But there are other accessories associated with it [such as replacement bows, bow rosin, shoulder rests, mutes, etc.] that I didn’t think about. And then when he moved on to the clarinet and the saxophone, I did not know that they needed reeds, and these reeds are different sizes and that [this] mattered in terms of the playability of the instrument. I also did not know how quickly he would go through them!”

Motivation Tips for Consistent Practice

There are many things that you as a parent can do to motivate your child to practice their instrument consistently. Here are a few:

- Find your child a tutor they like and can relate to. Often this can make the difference between musical success or failure. Your child’s teacher and/or local music retailer should be able to provide referrals. And if you (or your child) don’t like the tutor’s approach to teaching, or if either of you dislikes the tutor personally, don’t be afraid to make a change — the earlier, the better.

- Set goals. Ask your child if there is something they’d like to be able to accomplish on their instrument in the coming weeks or months. Find out what appeals to them and discuss it as being a potential goal. If a young player can articulate achieving something that is on their mind, they are more likely to go for it.

- Encourage your child to build a repertoire. Talk to your child about which pieces of music they’d like to learn, even if it’s a contemporary song that you personally don’t care for. Beginning students will always be more motivated to play the music they like.

- Keep the instrument on display, not hidden away. Having your child’s instrument out and visible in their room, or in the place they would normally practice, is always helpful. (Just be careful of heat, dust and/or passers-by to prevent damage.) There’s a difference between walking past a case sitting on the floor and feeling the urge to put in a solid playing session.

- Encourage your child to practice with others. Ask if they know of any other kids they’d like to play with, and then help them organize a jam session, even if it means driving your kid across town, or other kids to your home. Offer to assist by providing snacks, chairs and/or music stands.

- Encourage short-spurt practicing. It may be too lofty a goal to get any youngster to focus for long periods of time (other than on pursuits like video games), so ask your child to practice for just 15 minutes at a time so they can work on something — even something as simple as a scale — in a focused manner. Then ask them to return to their instrument later in the day for another 15 minutes to work on something else. Don’t be surprised if your child starts expanding those practice sessions on their own!

- Refer to it as simply “playing” and not “practicing.” The word “practicing” can sound like a chore, but “playing” implies having fun. Associating playing as an everyday activity sets your child up for the best chance of success as a musician, and will give them the ability to enjoy making music for years to come.

What to Do When Your Child Is Ready to Move On to Better or Different Instruments

As your child progresses musically, they may express a desire to move on (“step up”) to a better quality instrument. Many of today’s instruments (even beginner “entry-level” ones) are of good quality and deliver a reasonable sound. However, there’s no question that step-up instruments utilize better materials and design techniques, making them more durable and enabling them to deliver improved sound quality … and in some cases, they’re easier to play too. Be careful to encourage this desire, and if possible, arrange to rent or buy an intermediate-level instrument. (Your child’s teacher or a musical instrument retailer can provide recommendations.) The sheer fact that they are expressing an interest in playing a better instrument is a good sign that having one will help motivate your child further still, which will in turn allow their skills to improve more rapidly. Yamaha offers an especially wide range of both student and intermediate-level (as well as professional-level) instruments.

It’s also possible that your child may decide that they’d like to transition between related instruments (i.e., clarinet to saxophone, or trumpet to French horn), or even to a completely different type of instrument altogether. This is something that’s actually quite common: many professional musicians started on one instrument and switched over to another one early in their careers. As a parent, it’s important to validate that desire and accommodate your child’s wish if possible. Your child’s teacher and your local music retailer can give you further information and explain how musical skills translate from one instrument to the next.

Navigating Stressors

Visiting a music store for the first time to inquire about instruments for your child can be a stressful situation, especially if you don’t know the right questions to ask. This is where your child’s music teacher and a little online research can prove invaluable. If the salesperson is acting in a patronizing or demeaning way, or if he or she is rushing you, that’s an immediate red flag. Don’t be afraid to ask for the manager or walk out the door altogether. Their job is to help you through the process, not to make you feel bad about your desire to help your child learn an instrument.

If the music store staff won’t make specific brand or product recommendations, some online research should help point you in the right direction. You can also ask your child’s music teacher for recommendations, or find out the make and model number of the instruments the other kids in school band or orchestra are playing. Yamaha instruments, of course, are always a good choice!

Sometimes there will be high demand for certain instruments. If the music store doesn’t have the instrument you want in stock, perhaps there’s a waitlist they can add your name to, or maybe they can put you in touch with a different store that can ship it to you. Alternatively, ask the school’s band or orchestra director if there’s an instrument that can be borrowed from the school for a period of time. You can always talk to a family member to see if they have an instrument they will loan your child temporarily. These same strategies apply if you need an instrument urgently.

A Lifetime of Enjoyment and Pleasure

Learning an instrument at a young age can have a huge impact on music appreciation and can lead to a lifetime of enjoyment and pleasure. “Going to concerts and seeing my children play was like seeing them get their own instrument; it was precious,” says Angela. “When they go out to a concert or see a marching band at an amusement park, they know what kind of work goes into this,” adds Prudence.

“We take them to concerts and to see big bands play,” Angela says. “I think they can really appreciate how hard it is to play an instrument and how much skill it takes to create that sound. It definitely elevated them in terms of their appreciation of music. And it’s not just the playing that they took away. It’s that confidence, that group of friends they developed. They learned other skills beyond just playing music.”

Prudence concurs. “They learned to have huge respect for the others that they’re playing with. Knowing that if they didn’t practice their part, it messed it up for everybody else. That’s what teamwork was all about.”

Be sure to check out the Yamaha Parent Resources website.

Your Principal Probably Doesn’t Understand Your Job

“Can you send a couple kids to help with locker checks?”

That’s what our assistant principal asked — right in the middle of rehearsal. Clarinets were halfway through tuning. The concert was tomorrow, for goodness sake! I just stared at him for a second. Did he think this was a study hall? Did he not see 70 kids, in chairs, with instruments, ready to work?

It wasn’t malicious. It wasn’t even neglectful. It was just … uninformed.

That’s when it clicked: He really doesn’t get it.

It’s not just locker checks. It’s being left off school-wide announcements. Or being asked to “shorten your field time” when you’ve already booked the space. Or explaining — once again — that this competition is not a “field trip.” It’s the huge thing that we’ve been preparing for all semester.

You’re Not Being Ignored. You’re Being Misunderstood

I used to take it personally. When a dean walked past my room during rehearsal and didn’t even glance in. When I was left out of the Professional Learning Committee (PLC) meeting because “arts didn’t need to be there.” When a new staff member asked if I had any “free periods” because they saw me outside with the band.

I felt invisible.

Over time, I realized something: My admin didn’t see me because they didn’t know what to look for. To them, my job was concerts and parades. A few big events a year. Not the daily teaching, the emotional triage, the crisis texting with the bus company because one broke down three hours before call time.

They weren’t blowing me off. They just had no idea how much actually goes on in my music classroom.

Honestly, that’s fair. If I hadn’t lived this job for all these years, I wouldn’t understand it either. Even now when I try to explain what I do every day, I usually get a look that says, “Glad that’s not my job!” Because, again, they just don’t get it!

Start Small: Invite Them In

One of the first shifts I made was ditching the chip on my shoulder and just asking them to stop by. Not with a guilt trip. Not with any incentive.

I’d send a quick email like, “Hey! We’re running the full marching band opener today if you want to pop in — the kids are proud of it.” That’s it.

Sometimes they showed up, sometimes they didn’t. But the invite helped.

Eventually, I learned to plant little seeds. When a student organized an instrument petting zoo for elementary kids, I sent a photo. When we hosted a guest artist, I forwarded the schedule and said, “Would love to have you swing by.” One time, our counselor walked in on a rehearsal and said, “Wow, this is real teaching.”

Which … yes, it is.

Side note: I used to overthink this. I’d try to frame every invite like it was a press release (if you’ve met me in real life, you know that I can talk … a lot). I found that the more casual and authentic I made the message, the better it landed.

Don’t worry about looking polished. Worry about being visible. Write the email, press send — you’re done in a few seconds.

Document Your Wins (Quietly and Consistently)

This one took me way too long to figure out. I used to think, “If I just work hard and do good things, people will notice.” Guess what? They won’t. Not because they don’t care, but because everyone is doing a hundred things at once. Admin included.

So now I keep a running list — nothing fancy. Just a Google Doc with dates and bullet points:

- 10/3 — Led pep band at football game in the rain. Only two kids bailed. Victory.

- 11/6 — Concert had standing room only. Parent emailed: ‘I cried during the ballad.” (I did, too, but not for the same reason).

- 12/12 — Fixed the entire tuba section with one sectional and an unreasonable amount of Takis.

These are the things I forget about when I’m overwhelmed — but they matter. And when admin asks for an end-of-year reflection? I’m not scrambling. When I need to advocate for funds or justify a day off for a clinic? I have receipts.

This doesn’t need to be a PR campaign. It’s more like a survival kit for when you’re too tired to remember why you’re doing this.

Also, it’s incredibly validating on those “maybe-I-should-quit” days.

Set Boundaries Early (And Re-State Them Often)

The locker-check moment that I mentioned at the beginning of this article wasn’t the first time I was asked to loan students out. It started small: “Can I borrow a couple kids for a quick thing?” Then it became the norm. Suddenly, I was running an unpaid student temp agency.

At some point, I realized that If I didn’t protect my time, no one else would. So, now, I say things like:

- “We’re in performance prep mode, so I need all hands today. Can we check in next week?”

- “That student’s in the middle of a graded assessment. I can send them after class.”

- “This class is their team sport, their art class and their AP project all rolled into one. I need them here.”

Sometimes people get it. Sometimes they don’t. But I stopped apologizing for doing my actual job.

One year, a staff member jokingly called the band room “the land of no.” I took that as a compliment.

You’re not being difficult when you advocate for your students’ learning time. You’re being professional.

Also, random but important: If you don’t set these boundaries early, you will absolutely be the one they ask to cover lunch duty in May when everyone else is burned out.

You Might Be the Only One Explaining What You Do

One time I overheard a teacher say, “The band kids don’t have real finals, do they?”

That stung because our final that year involved a multi-day recording project, peer feedback and live performance. It may not be an online multiple-choice test with a bunch of data, but it was rigorous!

That moment reminded me: If I want people to understand the depth of what we do, I have to show them. So, I started being more vocal.

- I posted clips from final performances (with permission).

- I explained our rubric when I handed in grades.

- I invited teachers to sit in on small group projects.

Sometimes I’d drop lines like, “We’re in the middle of a unit on ensemble communication. It’s basically group dynamics with mouthpieces.”

Yes, it’s a little performative, but that’s the game. (After all, most jobs include a fair share of PR, and teaching is no exception.)

You don’t have to go full TEDTalk, but you do have to explain it — because no one else will. Otherwise, people assume it’s all marching and holiday concerts.

And when people assume that your work is easy or “fun,” they’re less likely to prioritize it. This part can be exhausting. If nobody explains it, your kids are the ones who will miss out — on time, space and stuff that actually helps. So, get used to explaining it — over and over again.

You’re Not Failing. You’re Just Unseen.

If you’re early in your career and feeling invisible, I want to say this clearly: It’s not because you’re bad at your job. It’s not because you’re not working hard enough. It’s because this job is odd and complex and emotionally draining — and most people don’t know what it looks like from the inside.

So, take a breath. Take notes. Say no when you need to. Invite them in when it feels right.

And when it’s one of those weeks — when the buses are late, the admin misses the concert and you’re reheating your dinner at 9:30 p.m. — remember that you’re building something they can’t always see.

But your kids see it — and that counts for a lot.

Five Tips to Get the Best Audio on Outdoor Movie Night

It’s Outdoor Movie Night! The screen is up and the projector’s running as you sit in the backyard with family and friends, streaming the latest superhero movie. The picture looks fantastic, but the tinny sound coming from the projector’s built-in speakers lessens the dramatic impact of the soundtrack and sounds nothing like you’d hear in a theater. What you need is an upgrade to your audio system.

But there are so many choices! Wired or wireless? Self-powered speakers or passive ones with an amplifier or receiver? Water-resistant or weatherproof? Stereo or surround? In this article, we’ll provide you with the information you need to assemble the best sound system for your backyard theater.

1. Choose Your Speaker Type

Let’s face it: Nobody likes to run wires. It’s particularly annoying if you have to do it every time you set up a temporary theater in your backyard or patio. For that reason, many people use a simple Bluetooth®-enabled speaker or speakers as their entire outdoor audio system. In addition to ease of setup, they have amplification built-in and run on rechargeable batteries. If you’ve got a projector (or outdoor TV) that supports Bluetooth, you can just pair them, and you’ll be good to go.

If you choose to go that route, you’ll do best with two speakers to handle the separate left and right channels. If you only use one stereo Bluetooth speaker, the left-right separation your audience hears will be virtually nonexistent.

But there are several drawbacks to using portable Bluetooth speakers. First, they tend to be a bit lacking in sound quality. Secondly, they often have limited power, so they simply can’t play very loud without noticeable distortion — a particular problem if your outdoor space is sizable. Then there’s the issue of latency (aka “Bluetooth Lag”). Often, Bluetooth audio gets slightly delayed compared to the video, causing lip-sync problems. Some people may not be bothered by that, but it will drive others to distraction.

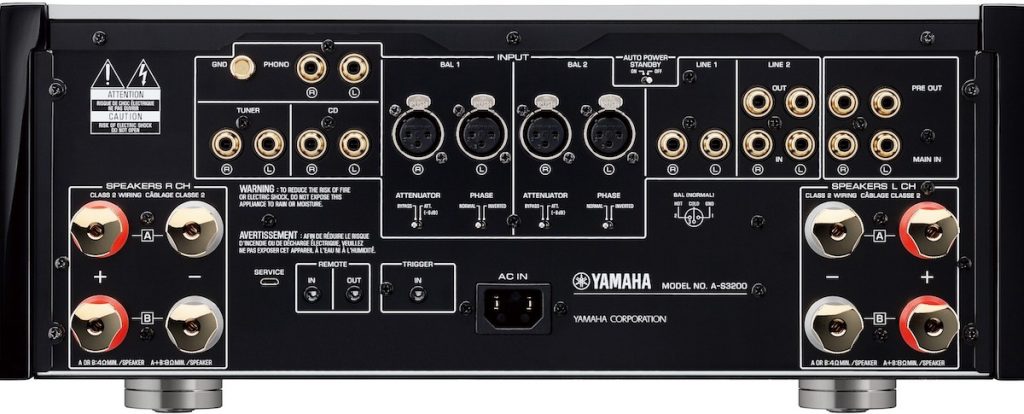

Wired passive speakers like the all-weather Yamaha NS-AW592 provide a more robust alternative and have no latency issues. Although you must connect them to an external amplifier or receiver with speaker cables, you can find plenty of weatherproof speaker models (you can also find weatherproof Bluetooth speakers, although they’re less common) or at least water-resistant ones. Yamaha offers a wide selection of weatherproof speakers in a variety of colors, enabling them to easily blend in visually, as well as offering superior sound.

One way to deploy weather-resistant speakers is to mount them permanently so you don’t have to put them up and take them down for each movie night. When combined with an outdoor TV (which will also be weatherproof), you can have a permanent backyard or patio theater that requires almost no work other than serving food and drinks.

Yet another option to consider is using a portable PA to carry the audio. The advantage to these is that they offer plenty of power, a selection of inputs, and pole-mountable speakers that you can place next to the screen (see below for placement suggestions).

A good example of this is the Yamaha StagePas 400BT system, which offers a built-in mixer, as well as 200 watts of power per side, which means that it can provide coverage in even relatively large spaces (see the “Assess Your Power Needs” section below). The StagePas 400BT also has both wireless Bluetooth and wired connectivity. If your projector or television doesn’t have Bluetooth, simply connect its analog audio line outputs to the inputs of the StagePas mixer. Bear in mind, however, that, like wireless speakers and subwoofers, PA systems are typically not waterproof so you’ll have to keep a close eye on the weather report and bring them inside when the festivities end.

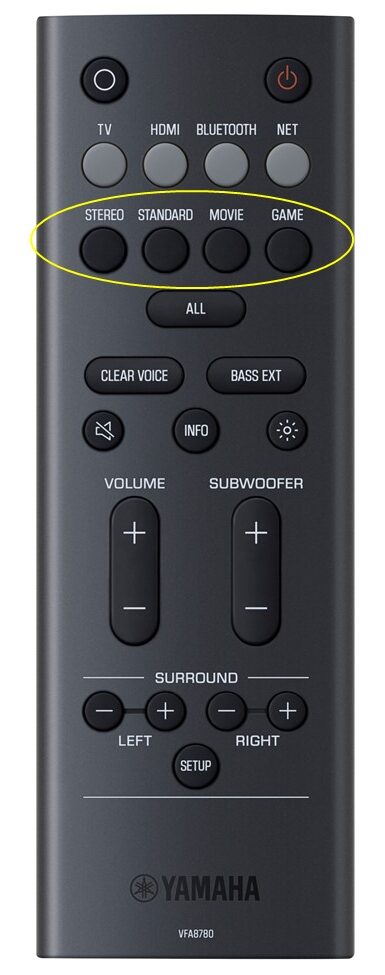

2. Plusses and Minuses of Surround Sound

Without question, your audio will sound more like a real movie theater if you hear it in a surround sound format such as 5.1- or 7.1-channel. The problem is that a surround system is more complex and requires additional time and effort to set up and tear down than a stereo system, which is part of the reason most people opt for the latter in their outdoor theater.

If you really want surround sound, the simplest way is to use a “bundled” system like the Yamaha YHT-5960U, which includes an AV receiver and all necessary speakers as well as a subwoofer. All you have to do with a system like this is to connect the audio from the projector to the receiver with an HDMI cable; however, like a PA, it’s not weatherproof, so you’ll need to set it up and take it down each time.

You can create a more permanent surround system with a standalone AV receiver like the Yamaha RX-V6A, along with five or seven passive weatherproof speakers and a weatherproof subwoofer. (Although those kinds of speakers are safe to leave outside, you will need to move the AV receiver indoors between backyard screenings).

3. Assess Your Power Needs

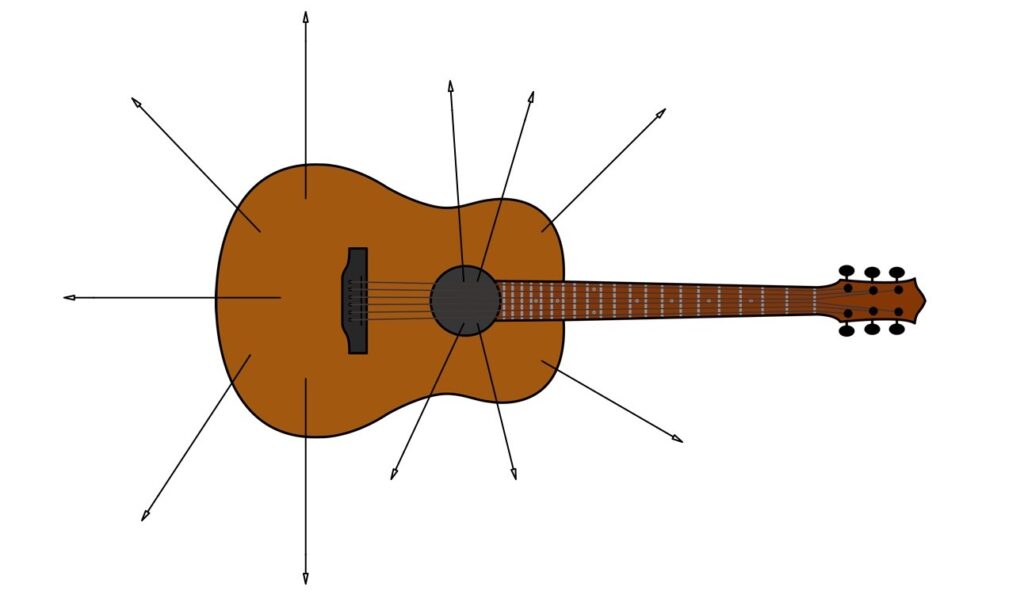

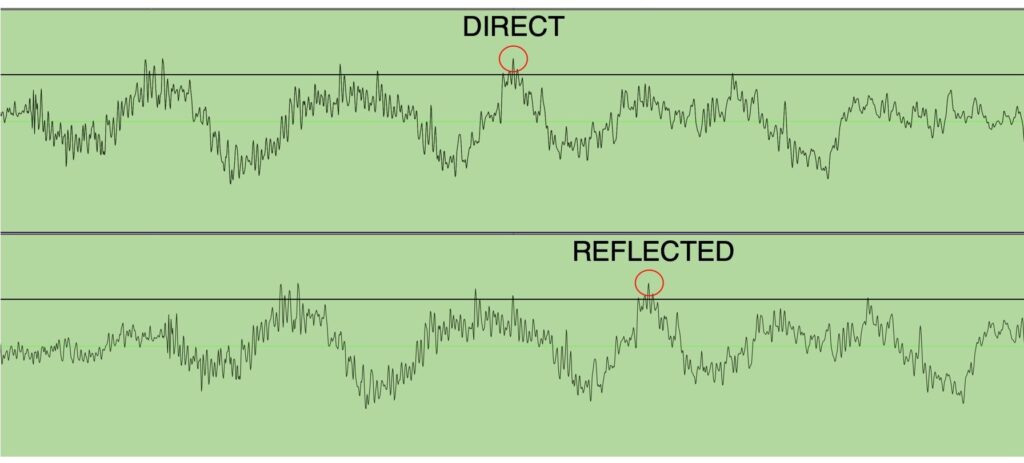

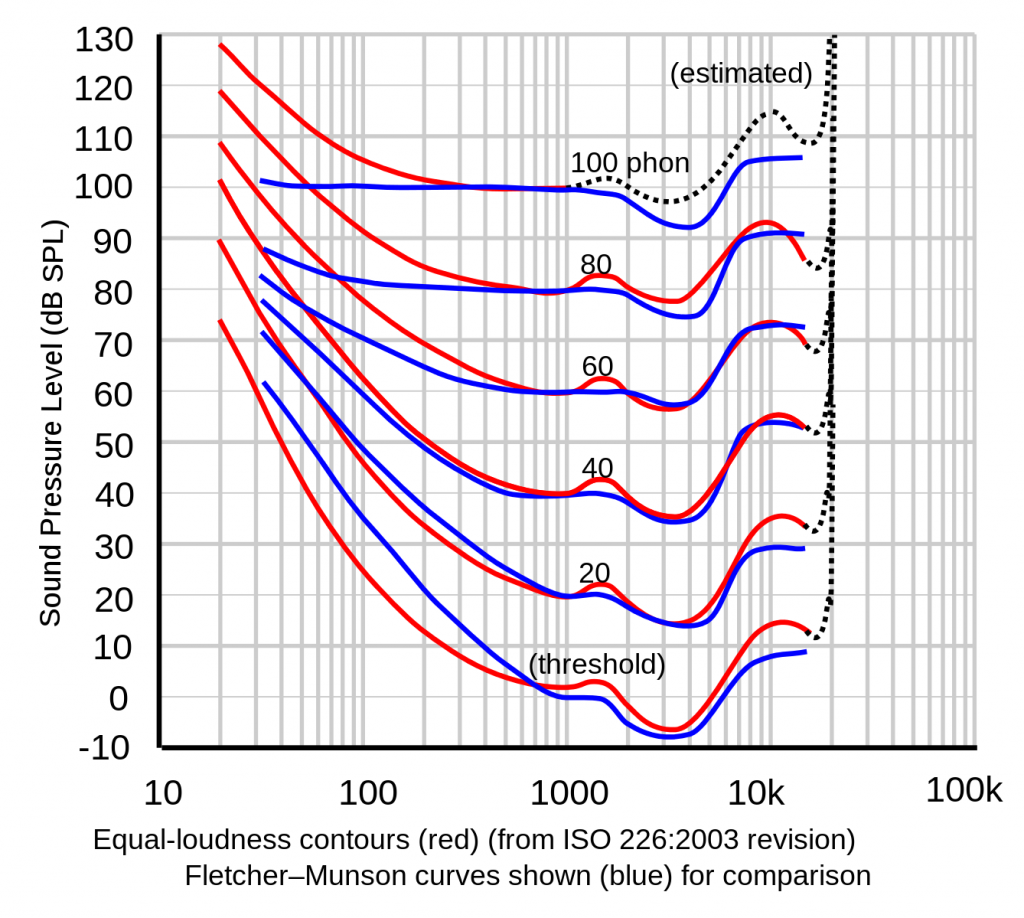

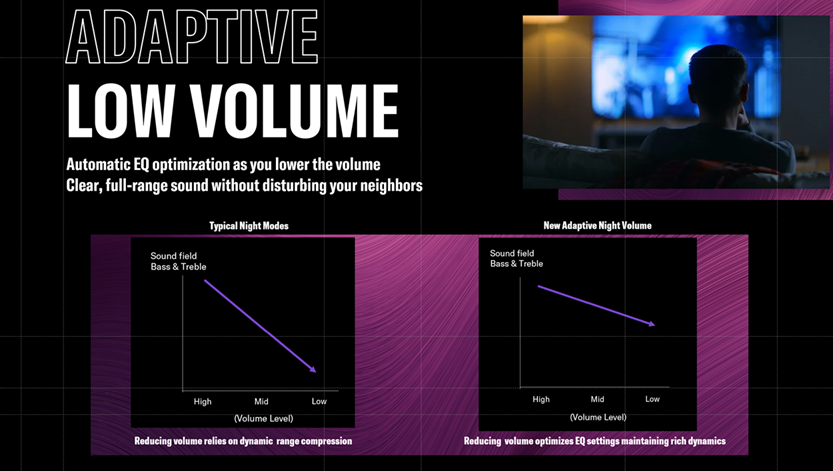

Outdoor systems need more power than an equivalent indoor setup, which may well influence the type of sound system you choose. One reason is there aren’t four walls and a ceiling to reflect sound waves like there are indoors. Another is that you’re likely to have considerably more ambient noise in your backyard theater, whether it’s street noise, your neighbor’s stereo or crickets and peepers chirping.

How much power you need depends on the distance between your speakers and listeners. The greater the distance, the more sound level is required, with the latter correlating to the need for a higher-powered amplifier. A principle called the Inverse Square Law applies when you’re calculating power needs versus distance. Sonic energy gets reduced by 6 dB each time you double the distance from the source of the sound.

To determine your total area, measure the square footage of your space (length x width). As a rough guideline, experts recommend 60 watts per speaker for spaces below 300 square feet, 100 watts for 300 to 500 square feet and 100 to 175 watts for 600 to 800 square feet. That said, a lot also depends on the ambient noise level in your backyard and the number and arrangement of your seats. The bottom line is this: It’s better to have too much power than too little.

Another advantage to having excess power is that it will provide sufficient headroom between your average (and peak) listening levels and the point at which the system distorts. If your system doesn’t have sufficient headroom, loud cinematic events such as explosions, gunshots or car crashes may sound distorted because they create peaks that are much louder than the average level of the soundtrack.

4. Place Your Speakers Wisely

The optimal placement for your outdoor speakers depends on many factors. If you’re permanently installing weatherproof speakers, you have several options. One is to mount them on a roof or wall or under eaves. You can even find outdoor speakers designed to look like rocks.

For a more authentic movie experience, you want to integrate the visuals and the sound. If you have a stereo system, this simply means placing one speaker on each side of the screen. The goal here is good stereo separation, but make sure not to spread the speakers out too much or people sitting off on the sides will only hear only one channel of audio. If you’re using a surround sound system, place the main left/right speakers on either side of the screen as you would for a stereo setup, and the center speaker directly behind or under the screen; the rear speakers should be placed behind the audience, to the left and right.

5. Be Prepared for Bad Weather

As we’ve seen, many backyard theater setups require you to include at least some gear that’s not waterproof or water-resistant. As a result, you’ll probably want to postpone your movie night when there’s a chance of rain in the forecast.

You also want to be prepared in case of an unexpected shower. Have some plastic tarps on hand to quickly throw over your gear in case you can’t get it inside fast enough. Also, plug everything into a multi-outlet box with a power switch (so everything can be turned off quickly) and be sure to connect it to an outlet with a GFCI circuit. These kinds of outlets are designed trip automatically when there is a break in the ground (as can happen if the rain starts pelting down), thus helping to spare your equipment (and, more importantly, your guests!) from getting a nasty shock, or worse.

The Joy of Playing Guitar Outdoors

One of my fondest memories of living in Nashville was getting together with my songwriter friends to play music on the weekends. We’d all gather at someone’s house with a dish of food, build a fire in the backyard and sing our freshly penned songs.

There’s nothing like watching fireflies dance like embers in the evening air, the taste of an ice- cold beer, laughter, sharing stories, and the sound of guitar players jamming together in the great outdoors.

As we all know, music sounds different depending on the environment it’s played in. A small coffee shop with a tiled floor and glass walls will reflect sound differently than an expansive ballroom with high ceilings and carpeted flooring.

But I’m convinced it’s not just the acoustics of the environment. I believe that, as sentient beings, our perception of music is also affected by our surroundings, and that includes the decor, the mood of the audience, how we feel emotionally and whether we are performing or enjoying the performance. Playing guitar outdoors not only changes how we hear music, but potentially how we feel about what we hear as well.

All my performances here in Hawaii for the past seven years have been at outdoor venues. There are some stunning locations here, of course, and sometimes the weather conditions and sunsets are so perfect that you could play for hours and hours. However, one of the first things you learn about playing outdoors on a regular basis is that the sound will always be different, even at the same venue.

Performing and Practicing Outdoors

Humidity, air flow and wind direction all have a profound effect on your sound when playing outdoors. I find that my sound changes dramatically — and for the better — after sunset. In fact, I choose certain songs to play at that time, not only for the emotional impact they will have on the audience as they watch the orange globe settle on the ocean, but also because those songs will sound incredible in the evening air.

If the wind is behind me at a gig, my sound travels away from me, and I find that I have to try harder to hear myself sing and play. But when the breeze is facing me, it tends to blow the sound back in my face. This provides not only a very enjoyable way to monitor the performance, but a great opportunity to react musically to what I’m hearing.

Students often ask me how to break out of a musical rut or how they can find a ladder to a new plateau of musical expression. My first question to them is, “Do you practice in the same chair, at the same desk, and in the same room every time?” If the answer is “Yes” (as it often is), I suggest they take their guitar to a new location in the house, yard, staircase or even the park to enjoy the effects of an alternate energy and ambient environment.

Taking an organic instrument like an acoustic guitar to a beach or park makes perfect sense to me. Acoustic guitars are naturally resonant works of art that self-amplify the music we play on them. I wonder if Mother Nature enjoys those resonances as much as we enjoy being in the presence of her beauty?

Changing your practice location to the great outdoors will invite new input and inspiration into your musical life. You may even find a spot that is so perfect for your creativity, you go there all the time for writing sessions and working on new ideas. Being in “the zone” this way allows the music to flow and potentially opens up new portals of creative information to download from the universal energy source.

When Inspiration Strikes

On sleepless nights, I often find the best use of time is to take my guitar outside, onto the back porch, and discover new ideas. The ear tunes in to the sound and resonance of the instrument when it’s dark, and I find that ideas flow better without the distractions of a busy day.

The musical piece in the video below was composed around 4:00 in the morning. The main melody, harmony sand the capo’d overdub all flowed through me and onto the guitar strings with relative ease.

In situations like that, I always make sure to record an idea of the arrangement and parts onto my phone, just in case I fall asleep again and forget the essence and feel of the composition.

The Video

As usual, I recorded the final music in my studio to capture the guitar tones with quality microphones. I had considered recording all of the parts outside, but there are too many extraneous noises on the farm where I live to do this beautiful instrument justice. The location where I filmed the video, however, does have wonderful acoustic properties, due to its slate floor.

The Yamaha LL-TA TransAcoustic guitar I’m playing here features lovely onboard reverb and chorus effects (no amp required!), to which I just added a small amount of hall reverb from an outboard signal processor for both rhythm parts, plus hall reverb and a touch of delay to the top note melodies.

The Guitar

The Yamaha LL-TA is a dreadnought-style acoustic guitar that sports a solid spruce top and solid rosewood back and sides. The body resonance is warm, and full: perfect for strumming, picking and single-note lines.

The LL-TA also comes equipped with an excellent gig bag, ideal for taking your guitar to inspirational destinations!

The Wrap-Up

We’ve all watched a movie in a theatre or on the couch at home. Maybe you’ve even enjoyed a drive-in feature from the backseat of a car, or a concert while sitting on a blanket in the park. As you’ve probably noticed, the sound and overall experience are vastly different. The popcorn tastes different outside, the audio travels lightly on the breeze, and the emotional content of the visual has a unique effect on us in the open air.

The same holds true for music. Being sun-kissed at a festival or covered in mud while watching your favorite band is something we should all experience at some point in our lives. It’s raw energy, unconfined to finite wall dimensions. Music in the great outdoors changes you, expands your perceptions and leaves its mark on you forever.

Photographs courtesy of the author.

Check out Robbie’s other postings.

How To Think Like Your Bass Heroes But Sound Like Yourself

Most of us fall in love with bass after hearing or seeing someone else play. After that initial life-changing rush that makes us say, “I want to do that!” we might pick up the instrument and decide to sound as much like our hero as we can. The path to greatness, however, lies in finding your own unique sound. How exactly do you do that? By dissecting your heroes’ sound — their tone, gear, technique, harmonic tendencies and influences — and putting your own spin on them.

MINDSET MATTERS

Before you rush out and buy your idol’s signature bass, learn how they think; watch and read interviews to understand how they got where they are. Thanks to YouTube, there are countless videos where great musicians like Victor Wooten and Nathan East articulate the lessons they’ve learned, and understanding their mindset can help you decide what works for you and what doesn’t. As you search for your own voice, learn from the things that helped make them successful (high standards, an outgoing personality and a strong work ethic, for example), but avoid making the same mistakes they did.

WHAT’S THAT SOUND?

You don’t have to have the exact same gear as your heroes, but if emulating their sound is important to you, hearing yourself through similar equipment can be helpful. Figure out what it is about them that catches your ear and then do your best to recreate that sound. Every element of a player’s tone — the bass, the strings, the onboard preamp (or lack thereof), the amp and speaker cabinet, their effects — contributes to the sonic recipe that works its magic on you.

Know also that your gear has a big impact on your technique: Veterans like John Patitucci understand that string height and string spacing change the way you play. Going on this journey will help you find the gear that works best for you, even if it’s not the same equipment your hero uses.

GET TECHNICAL

Does your hero play melodies with a pick like Peter Hook? Do they have a lightning-fast right-hand technique like Billy Sheehan? Do they have a clean, blazing fingerstyle sound like Vincen García? Learning your favorite player’s favorite techniques will help you understand what they consider appropriate for the genre (or genres) they play most. If they step out of their comfort zone, notice what made them try a different approach. Their habits and their experiments will help you understand how they view their instrument, and it’ll give you a chance to choose what works for you. As you try their techniques, see what comes easily and what’s worth working on.

HARMONIC AND RHYTHMIC TENDENCIES

Think of a player you love, and chances are you’ll be able to recognize their sound within just a few seconds. Knowing why and when your idols make certain musical decisions (and how their styles have changed over time) will clarify how they think of harmony, melody, tempo, rhythm and improvisation. Listening to John Patitucci talk about a 12-bar blues, for example, is a great way to learn how he solos, plays walking basslines and supports the rest of the band. Transcribing basslines and/or listening to isolated bass tracks (like this one of Tony Kanal’s bass line on No Doubt’s “Don’t Speak”) is the best way to absorb their musicianship so you can decide what you’d like to copy or how you’d like your sound to differ. Even your inability to precisely imitate your heroes may reveal something that’s uniquely you.

INFLUENCES

Before your heroes had a sound of their own, they were likely trying to copy someone, too. Many influential electric bass players of the 1960s and ’70s, for example, can trace their initial inspiration back to Motown session legend James Jamerson. Studying Jamerson’s style and sound will give you an excellent foundation, as well as a window into the creative ways that so many players have incorporated his musical approach and style into their own playing.