The Recorder: It’s an Instrument, Not a Toy

For most of us, a plastic recorder was the first musical instrument we encountered back in elementary school, and for that reason it’s something we tend to think of as a childhood toy. However, the recorder is actually a serious instrument, with a rich history that goes back to ancient times. Intrigued? Read on …

History

One of the very first recorders was the Quena — a Latin-American instrument that dates back to the ancient Incan Empire. The modern recorder was developed in Europe during the Middle Ages. From the second half of the 15th century to the 17th century it was frequently used in live performance, but in the late 18th century it began to be overshadowed by the flute, a related instrument, though one that differs significantly in terms of volume and timbre. In fact, the recorder was originally known by the name “flute.” Eventually, the modern flute began being referred to as a transverse flute in order to differentiate it from the recorder.

Recorders of the 17th century had a cylindrical bore, and a timbre that was broader and less piercing than that of today’s instruments. Initially, they played a substantial role in ensembles that included vocals, as well as in all-recorder ensembles (called “whole consorts”) as well as “broken consort” ensembles that included stringed instruments such as violin.

With the advent of the Baroque period (1600 – 1750), the recorder came to be used almost exclusively as a solo instrument. Because a more piercing sound was deemed desirable, the bore of the recorder was made conical. As a result, higher pitched harmonics became more prominent, yielding the distinctive timbre we hear today.

During this period, a great many “sonata” and “concerto” works were produced for the instrument — in fact, it could be said that this was the golden age of the recorder. In addition to G. F. Handel’s “Seven Sonatas” and “Two Trio Sonatas,” a number of operas and oratorios featured recorders. They were also used for solos in J.S. Bach’s “Brandenburg Concerto” No. 2 and No. 4, and as an instrument for performing obbligato in many cantatas. In addition, Italian composers such as Scarlatti and A. Vivaldi wrote numerous sonatas, triosonatas, and concertos for recorder — “Concerto in C-Major for Sopranino Recorder and String Orchestra” is one that is particularly well known.

From the time of the classical period, when works by Mozart and Beethoven became popular, orchestras began to develop, but due to its limited volume, the recorder was unable to hold its own. And since the flute was more expressive, the recorder gradually became less popular, although it still continues to be used widely in performances of Baroque music. Today, the recorder is the most popular instrument in early music education, with widespread usage in elementary schools the world over.

Varieties of Recorder

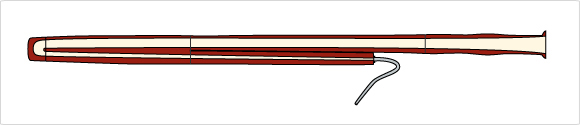

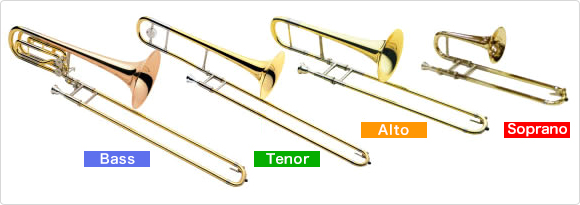

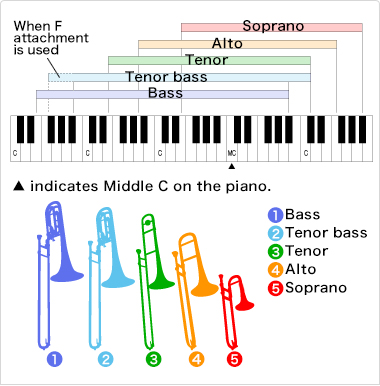

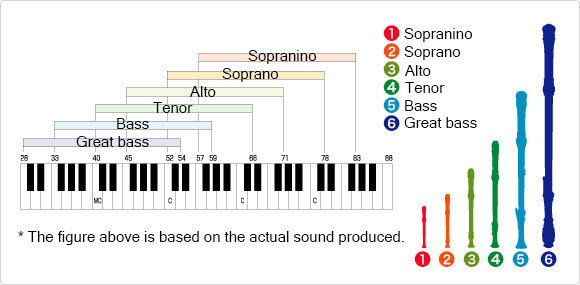

Recorders come in many varieties, from the sopranino recorder, which is about the size of a Sharpie™, to the great bass recorder, which is as big as a piece of furniture. The type most frequently used for solos is the alto recorder. There are also quartet ensembles that perform with four types of recorders; soprano, alto, tenor and bass.

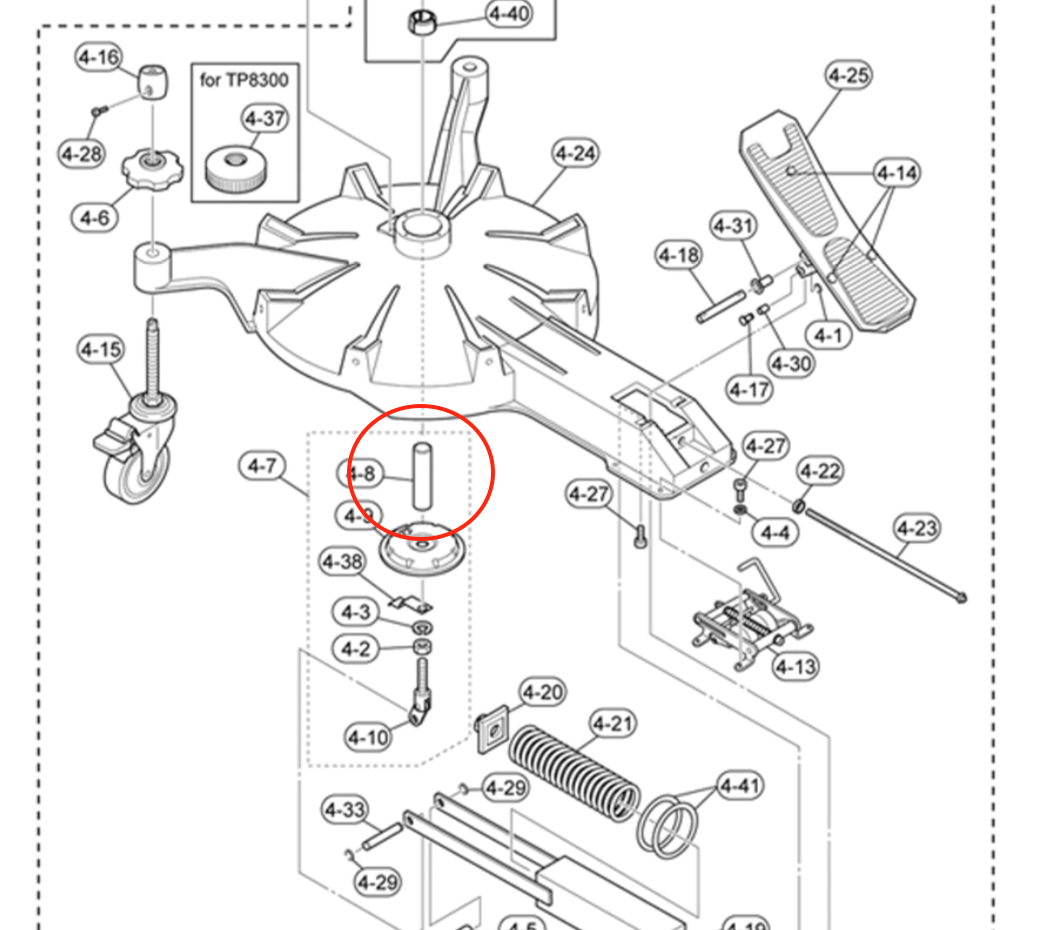

Because they are so big, some bass recorders and great bass recorders cannot be blown directly with the mouth as with smaller-sized instruments. For that reason, a long pipe (called a blowpipe) extends from the sound-generating part of the instrument to the lips. Furthermore, as the gap between tone holes is wider, keys are added for the locations where they cannot be covered directly with the fingers. However, since the blowpipe is just a simple structure to channel the breath, anyone can quickly produce sound, and the fingering is almost entirely the same from recorder to recorder, although the timbre produced varies.

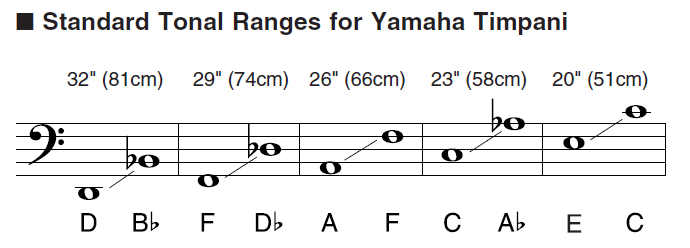

As the size of the recorder increases, its pitch range gets lower. Great bass recorders are twice the length of tenor recorders, and there are also contrabass (sub-bass) recorders, which are twice the size of bass recorders. In addition, there are many types within the soprano and alto recorder families, each about half an octave higher in pitch than the next larger-sized one, as shown in the chart below:

Plastic vs. Wood

Recorders were originally made of wood, but today there are of course also plastic recorders, which are moderately priced and robust yet produce a solid sound. Plastic recorders also have the advantage of relatively straightforward maintenance, although water droplets can sometimes clog the windway (airway) since these instruments do not absorb moisture. (This can be easily remedied by lightly tapping just above the windway, or by blowing or sucking to force out the droplets of water.)

The ABS material used in Yamaha plastic recorders gives these instruments exceptional impact resistance, making them extremely durable. They offer a clear timbre and exceptional intonation, and their overall pitch can be adjusted by simply changing the extension of the head joint, allowing the recorder to be tuned to participate in an ensemble with other musical instruments.

Wooden recorders have a distinctive, rich tone that is not generally matched by plastic recorders. However, wooden recorders are more expensive than plastic models, and require more maintenance. They can be made of rosewood, ebony, maple, Kingswood or Castelo wood. In general, the softer woods produce a softer sound, while the harder woods produce a more pronounced sound, though there is a broad expressive and timbral range within each variety.

Two Different Fingerings

In the 1920s, instrument designers in Germany felt that the standard Baroque recorder was too difficult for beginners to learn, since some notes put the player’s fingers in positions that can feel uncomfortable or unnatural. Because of this, they made a small change to make those notes easier for a beginner to play. As a result, there are two varieties of recorder in common use today: “Baroque style” and “German style.”

In “Baroque style” recorders:

– Soprano F (Alto B♭) tone fingering is not in sequence with the rest of the scale.

– Fingering for sharp (♯) and flat (♭) notes is simple.

– The same fingering can be applied when playing recorders that differ in size.

In “German style” recorders:

– Soprano F (Alto B♭) tone fingering is in sequence with the rest of the scale.

– Fingering for sharp (♯) and flat (♭) notes is difficult.

– The same fingering cannot be applied when playing recorders that differ in size.

On a soprano recorder, playing a simple melody with a narrow range in a pitch range such as C major or F major presents no particular issue with a German style recorder, but performing a piece with a wider range or accidentals (sharps and flats) is more difficult. Also, since models other than the soprano are mostly made in the Baroque style, if fingering is learned on a German-style soprano model, it cannot be applied on a Baroque-style instrument. For more information, see our blog article “Recorders: Baroque vs. German”

As you can see, a recorder is much more than just a toy! And now that you’re long out of elementary school, it might just be time for you to reacquaint yourself with this wonderfully expressive yet easy-to-play instrument.

This posting is excerpted from the Yamaha Musical Instrument Guide. For more information about Yamaha recorders, click here.