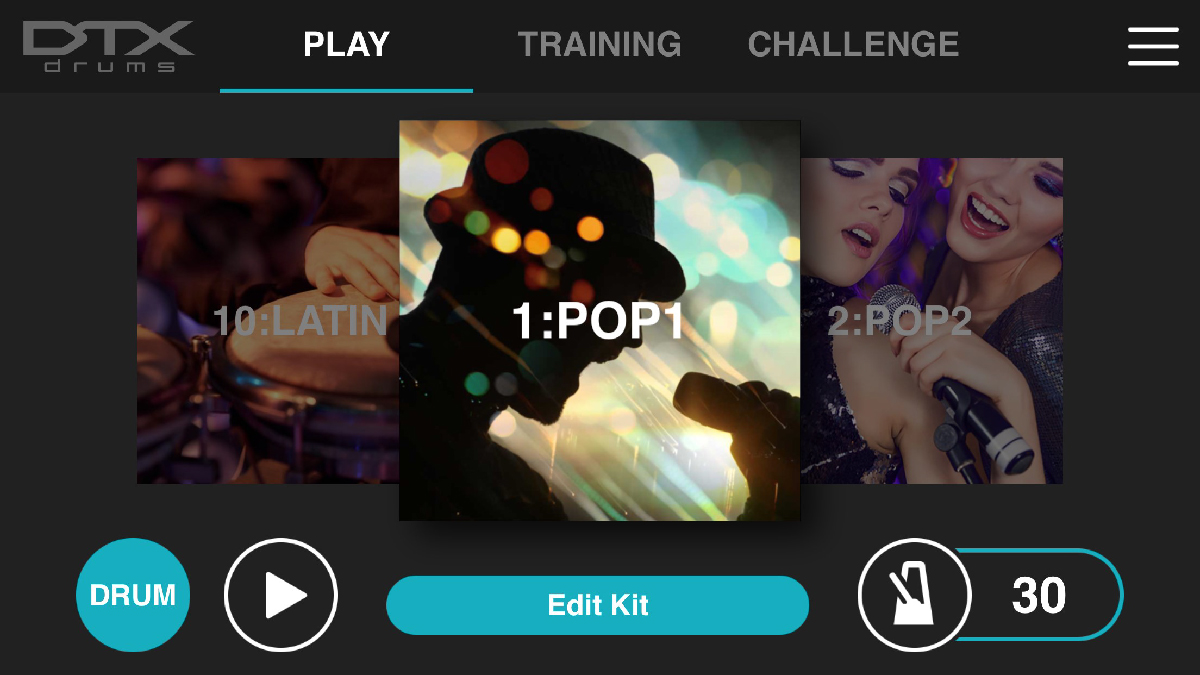

Mixing for Virtual Reality and Video Games

If you’re accustomed to mixing music in stereo (or even conventional surround sound), you’ll likely find that mixing for virtual reality (VR) and video games is fundamentally different. In this posting, we’ll look at the way those kinds of projects are mixed, and discuss how the new features in Steinberg Nuendo help make those endeavors easier.

Alphabet Soup

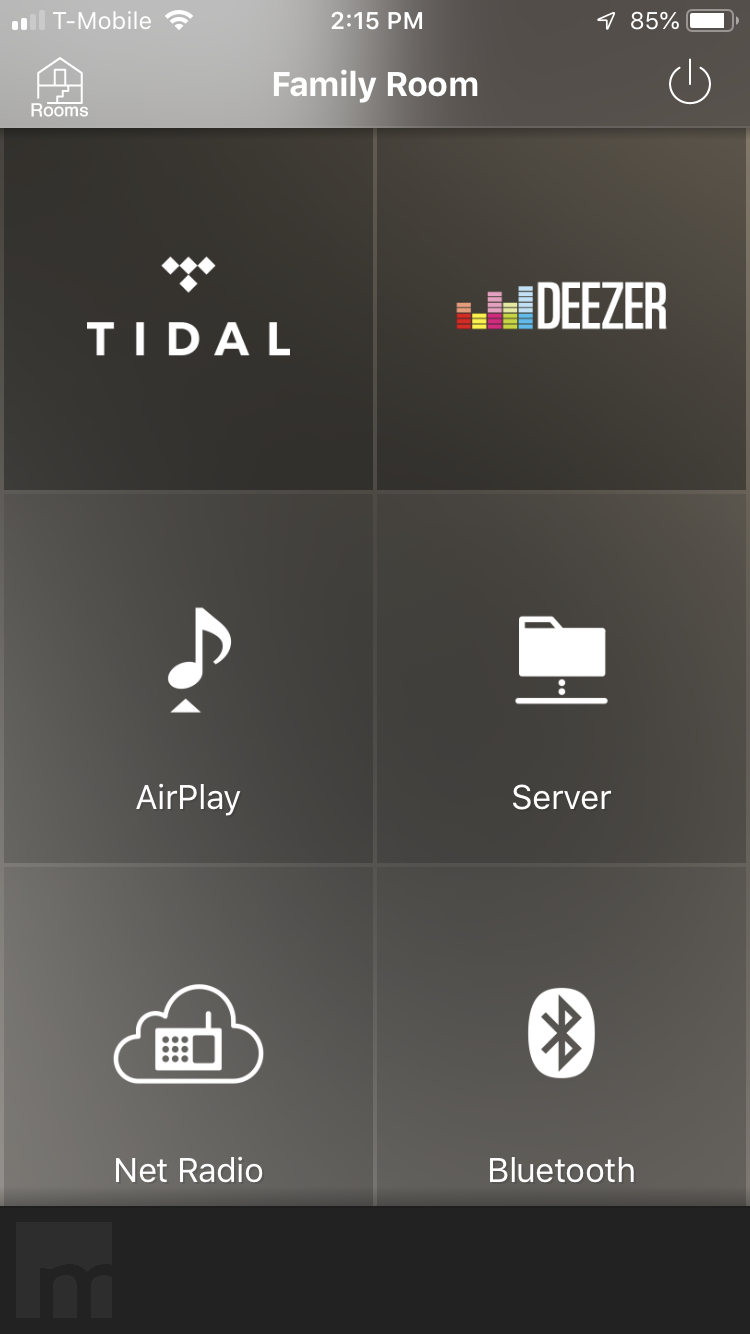

The most popular format used in audio for virtual reality is Ambisonics. In addition to giving you left-to-right panning, as in stereo, Ambisonics also provides for up-and-down and front-to-back panning. The result is full 360-degree audio — perfect for immersive content. Ambisonic audio is used in Facebook and YouTube’s VR content and YouTube 360-degree videos, as well as in VR games.

There are several different quality levels, with the most commonly used called “First Order Ambisonics B-Format.” Additional levels (known as Second Order and Third Order Ambisonics) offer larger channel counts and allow for more accurate positioning of objects in the spherical field. However, they’re more complicated to execute.

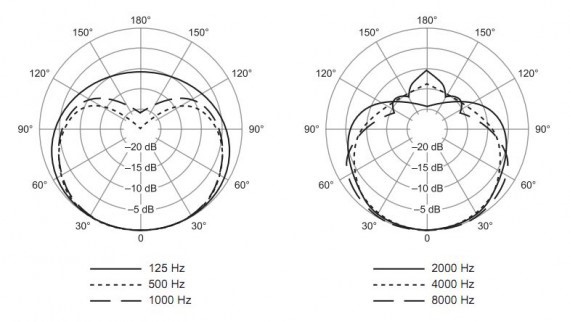

There are several ways to create Ambisonic content. One is to record live audio with a specialized Ambisonic microphone that utilizes multiple capsules to capture 360-degree sound into a dedicated type of 4-channel audio file.

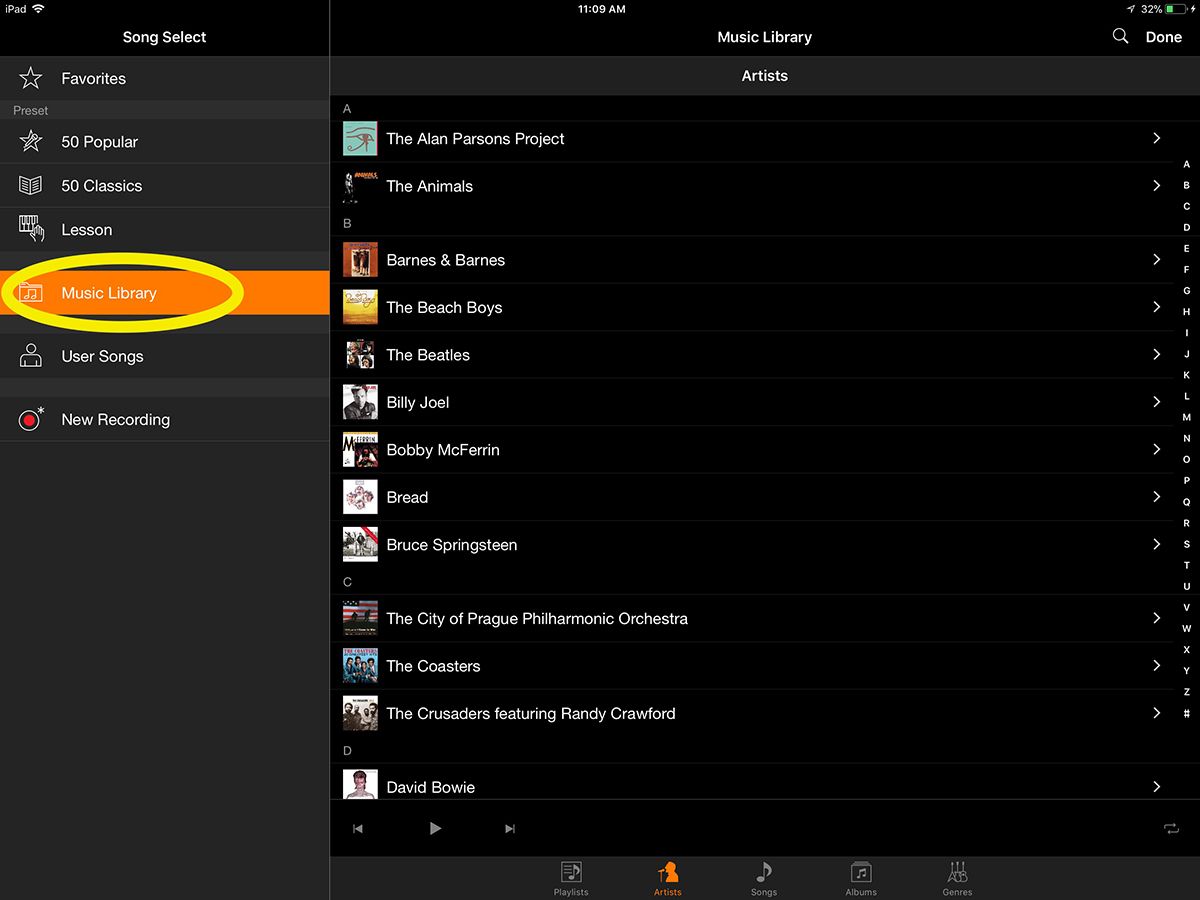

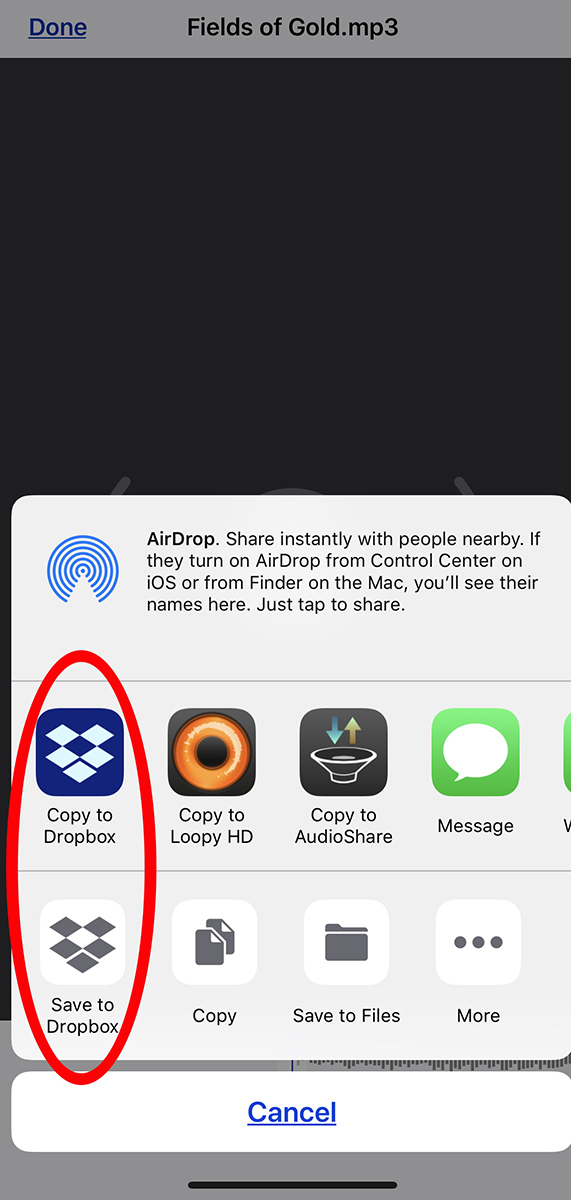

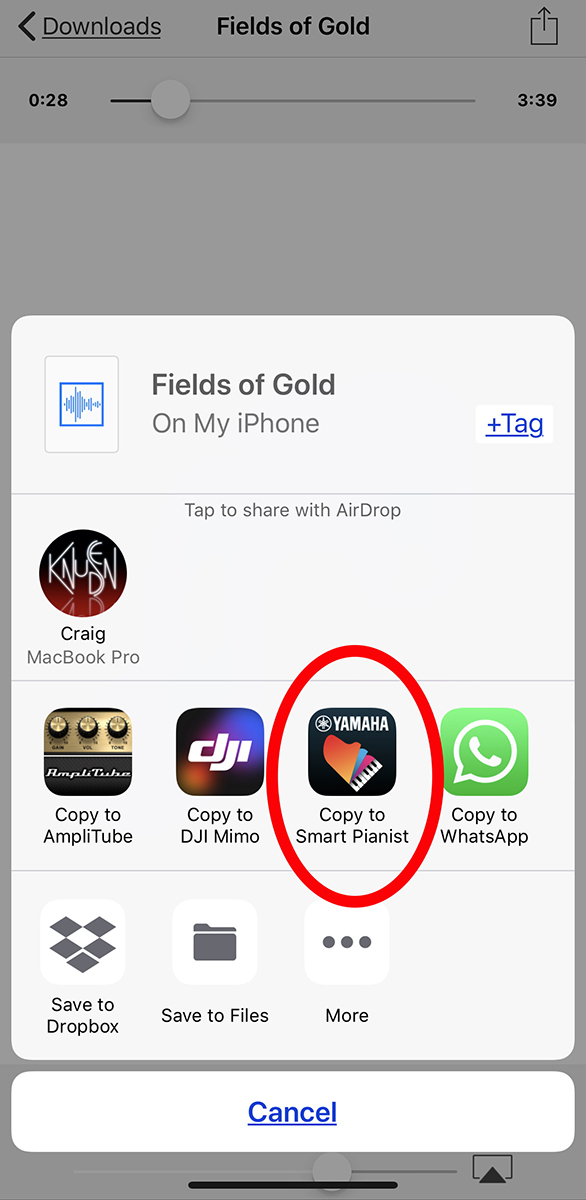

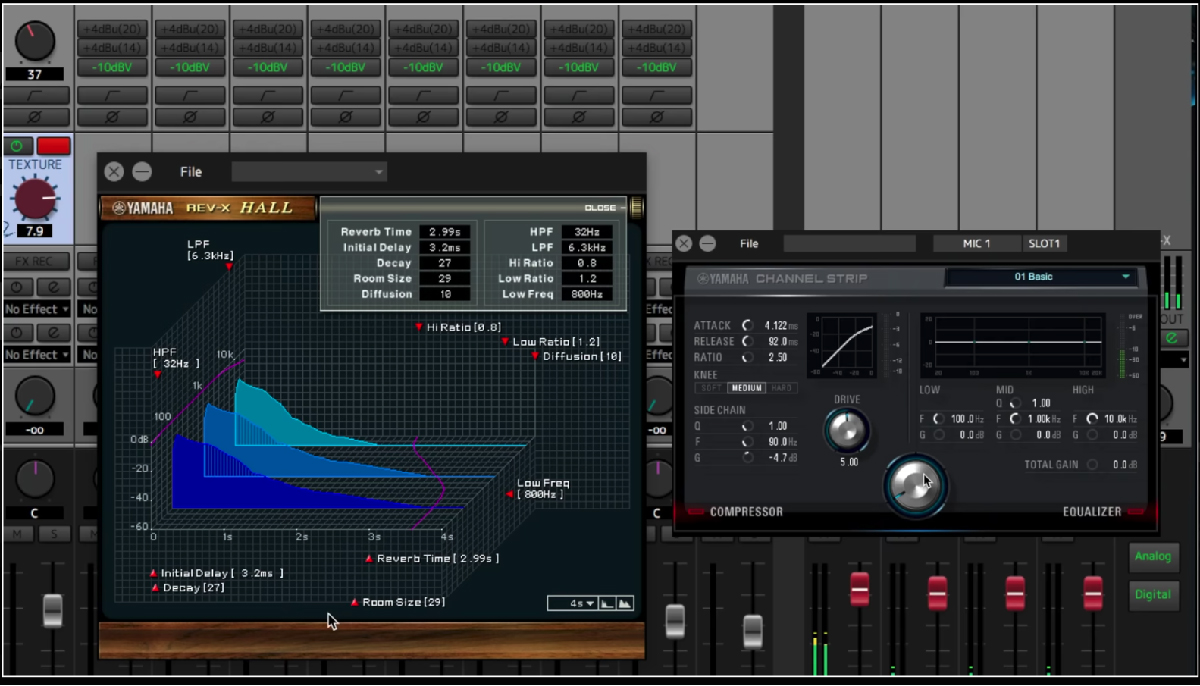

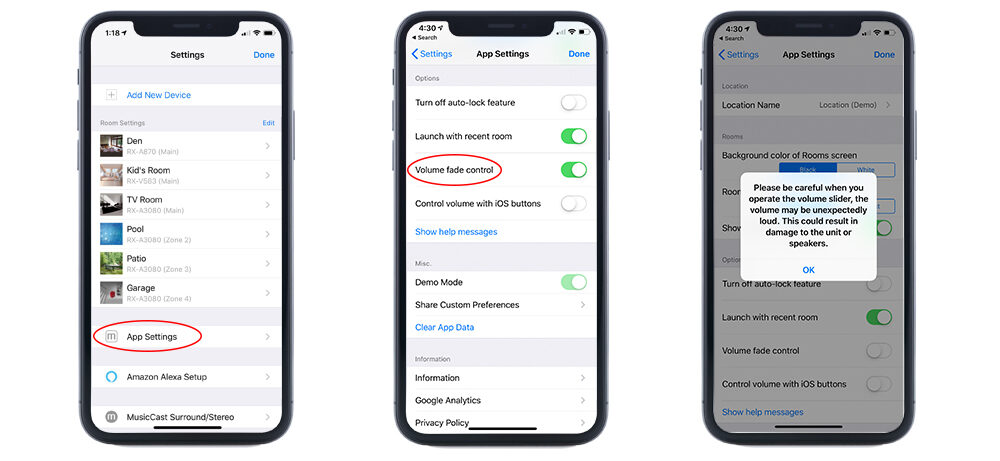

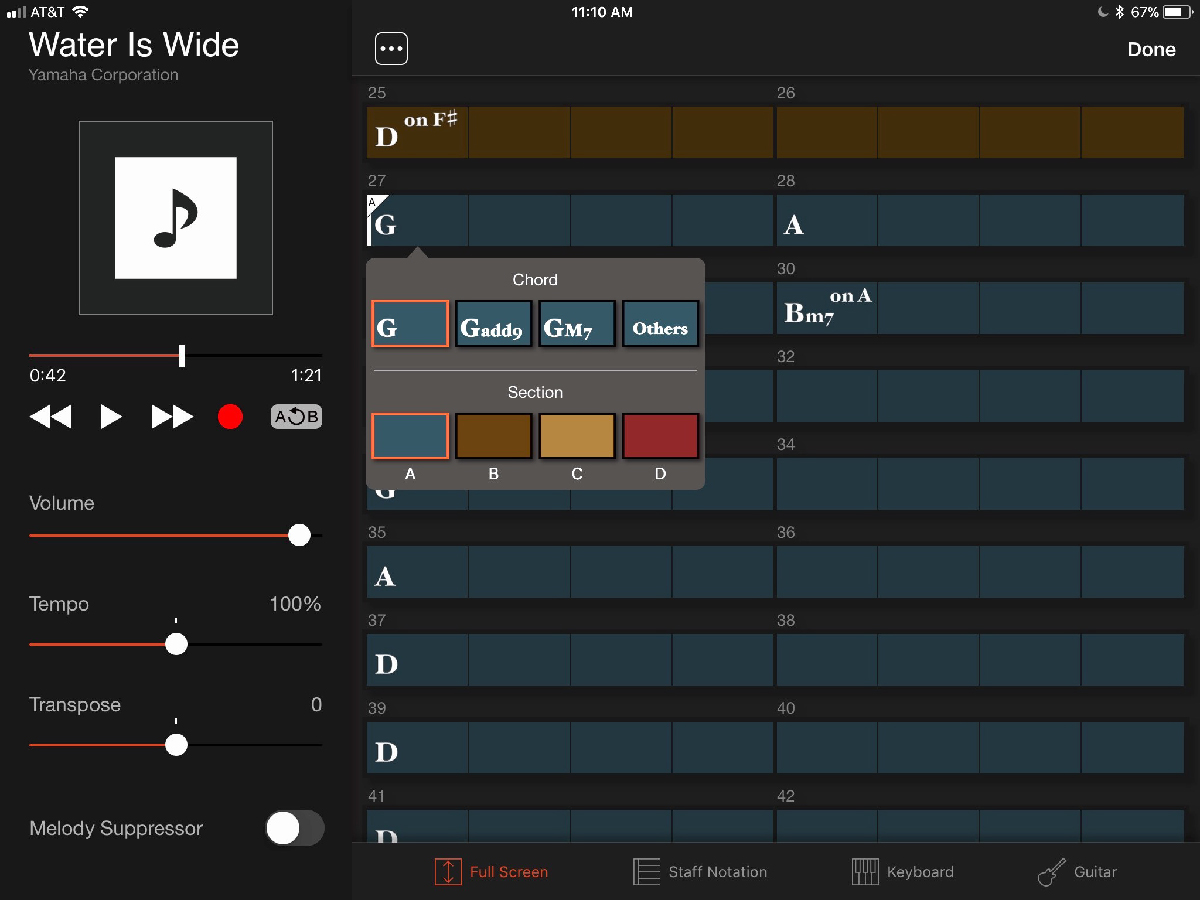

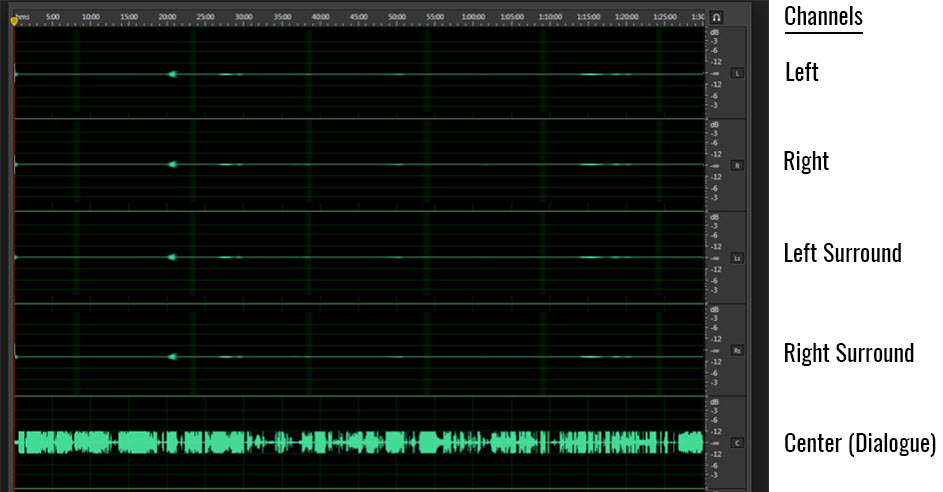

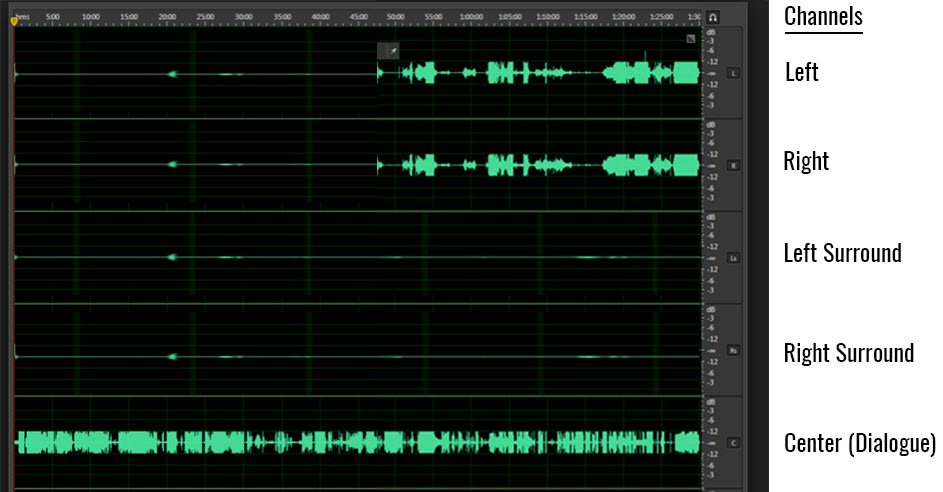

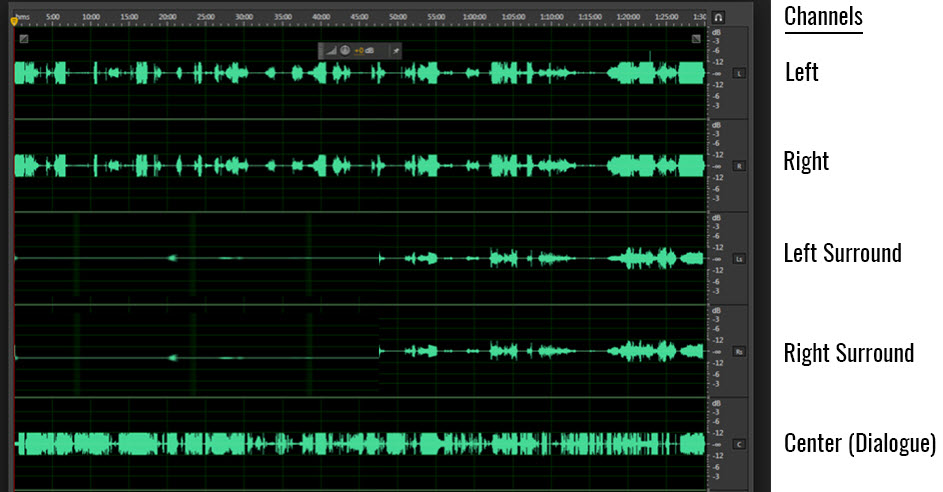

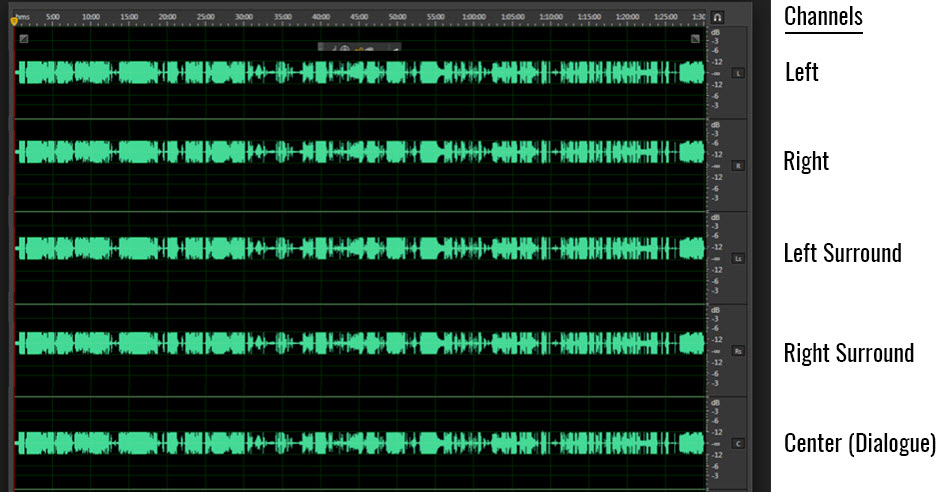

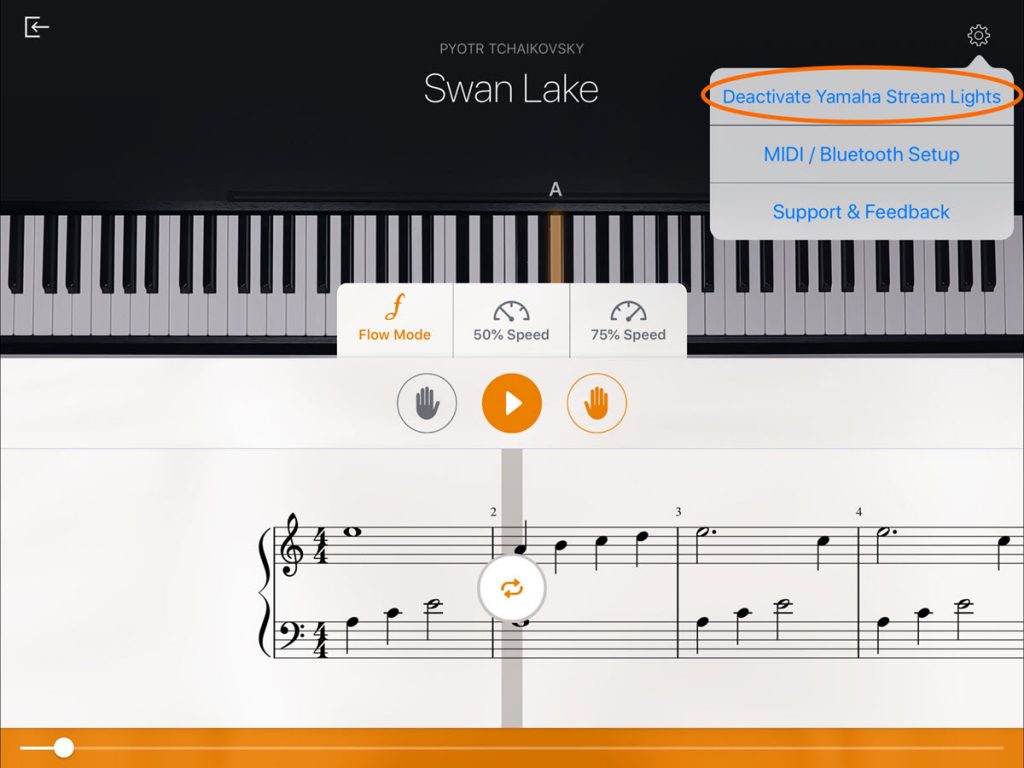

The second way is to create a 360-degree Ambisonic mix in a compatible DAW such as Nuendo, using conventional audio tracks (individual mono, stereo or surround tracks) as source material. After adjusting the volume and adding effects to those tracks in the mixer, you can position (and move) each in the Ambisonic sound field using an Ambisonic panner plug-in such as the Nuendo VST Multi-Panner, which, as a bonus, also converts the mix to B-Format.

Alternatively, you can use your DAW to mix non-Ambisonic audio together with mic-captured Ambisonics audio into a B-Format mix. For example, if the video for a VR project includes a street scene in a city, you could capture some ambient sound with an Ambisonic mic to serve as the primary structure (the “bed”) of your audio track. Then you could mix in supplemental audio such as dialog, sound effects or music to go along with it. Using VST Multi-Panner, you could then pan those extra elements to go wherever you needed them in the 3D sound field, in relation to the “bed” track.

Secret Decoder Ring

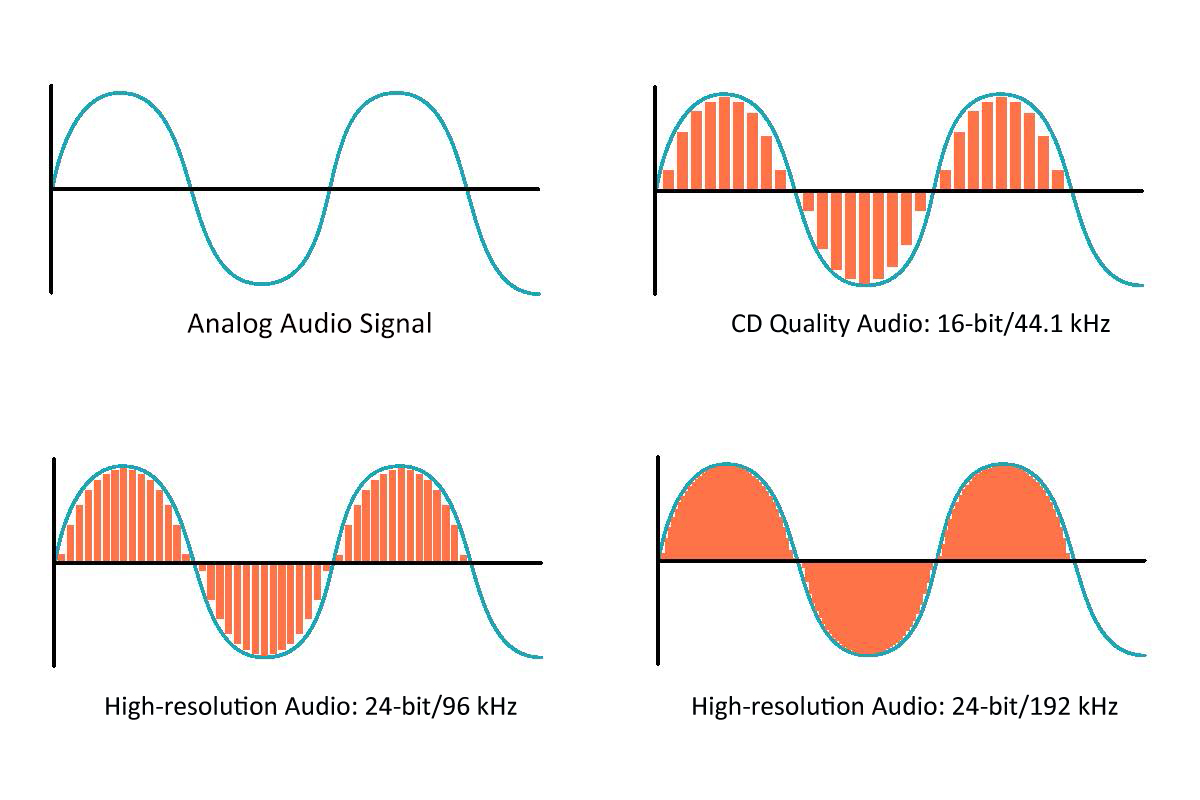

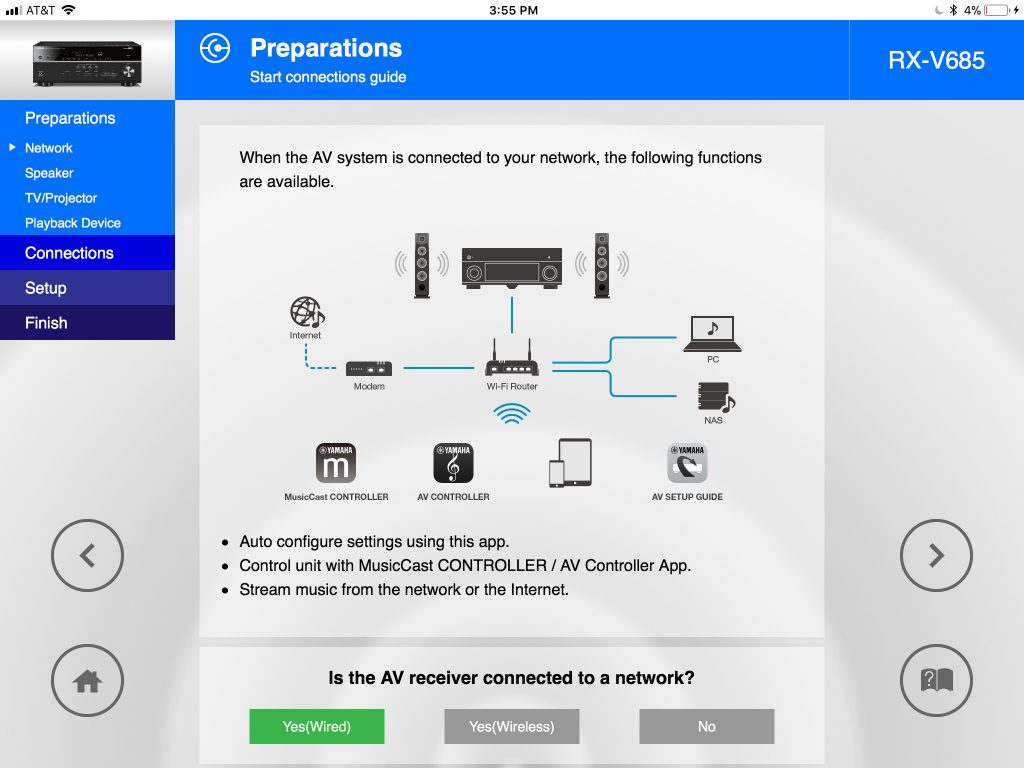

In any kind of mixing, it’s always good to be able to listen to your mix the same way an end user will. However, monitoring 3D Ambisonic audio over a stereo monitoring system presents a challenge. Even if you had a full Dolby Atmos® speaker system (a surround system with front, back, side and overhead speakers), you still couldn’t listen directly to B-Format, because it contains no speaker-specific information for the content, only directional data for the 3D sound field.

To listen to 3D Ambisonic audio over a stereo system, you need to first decode it, using a plug-in such as the Nuendo VST AmbiDecoder on your monitor bus. This plug-in converts B-Format into a variety of formats for monitoring. The most practical is binaural 3D output for stereo headphones, which provides a simulated 360-degree listening environment. It’s especially useful because it simulates the way most people experience VR and 360 video content: through headphones of some sort, such as a VR headset.

In Nuendo v.10 and higher, Steinberg upgraded the VST AmbiDecoder plug-in with two additional modes for enhancing Ambisonic content and also added a new feature that allows you to use your stereo monitors to listen to Ambisonics content.

Head’s Up

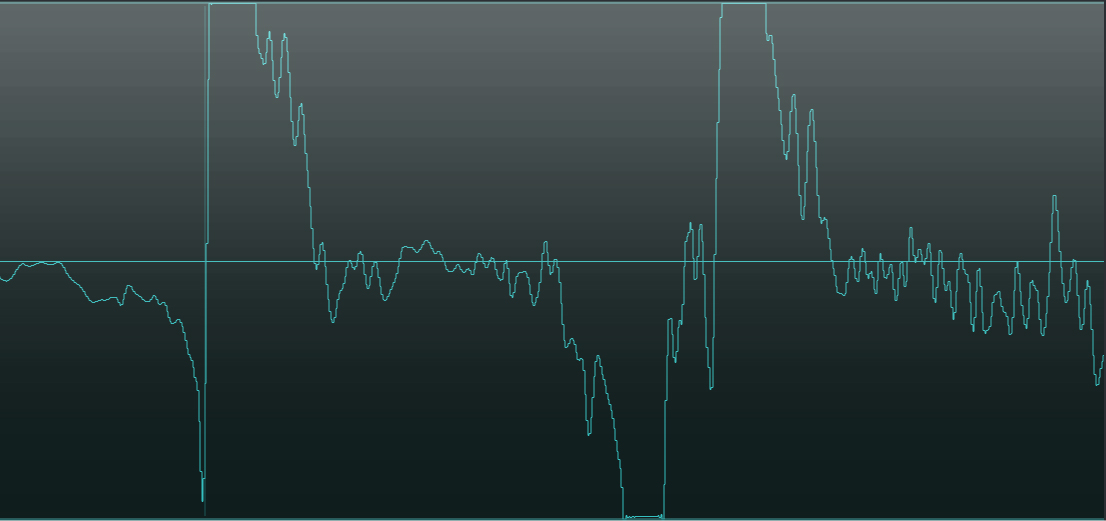

Then there’s the issue of head tracking. B-Format Ambisonics can respond to head movement and rotate the entire spherical image in your headphones, as if you were wearing a VR headset. All you need to add that capability is a relatively inexpensive head-tracking device that clips to the top of your headphones and can be tracked by a compatible DAW such as Nuendo.

When you’re making placement decisions during an Ambisonics mix, you can designate any of the tracks in your mix to be “head locked,” which means they’ll stay anchored in place even when the user changes head positions. Mixers often head-lock elements like music and voiceovers so that they stay centered while the rest of the audio follows the listener’s head movement. Incorporating head-tracking into your mixing setup will help you check that the various elements are behaving as they should in reaction to the listener’s movement.

Nuendo 10 also added support for DearVR Spatial Connect, a system that allows you to mix while wearing an actual VR headset for watching the video while adjusting audio balances using VR hand controllers. This puts you inside the environment in which the game or VR video will be viewed by the end user, thus dramatically aiding in your mixing decisions.

Gaming Improvements

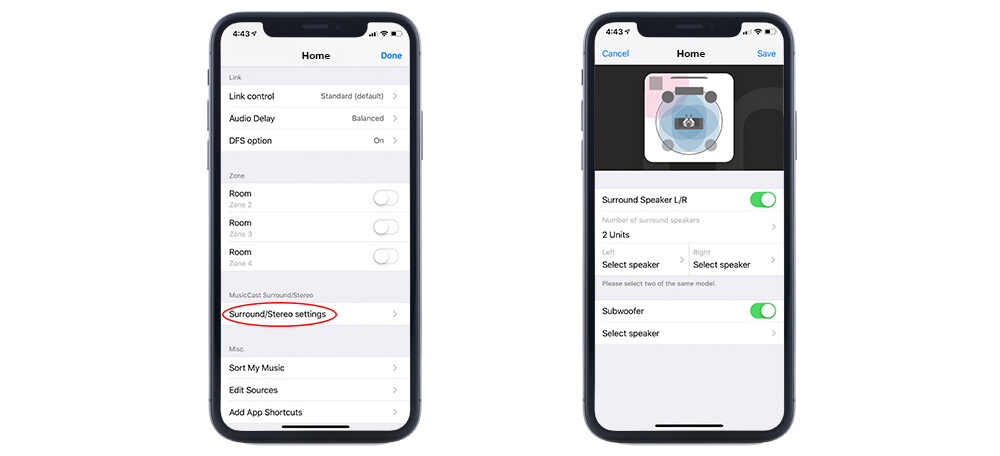

Nuendo has long been optimized for game audio workflows, thanks to something called “Game Audio Connect,” a toolset that enables a direct connection to Audiokinetic’s Wwise® game audio middleware. Starting with Nuendo 8, an enhanced version (“Game Audio Connect 2”) added the ability to transfer interactive sections of your compositions from Nuendo into Wwise as music segments, including audio and MIDI tracks as well as cycle and cue markers. In addition, Game Audio Connect 2 allows you to create Nuendo projects directly from Wwise segments, effectively allowing you to use Nuendo as a MIDI editor for Wwise.

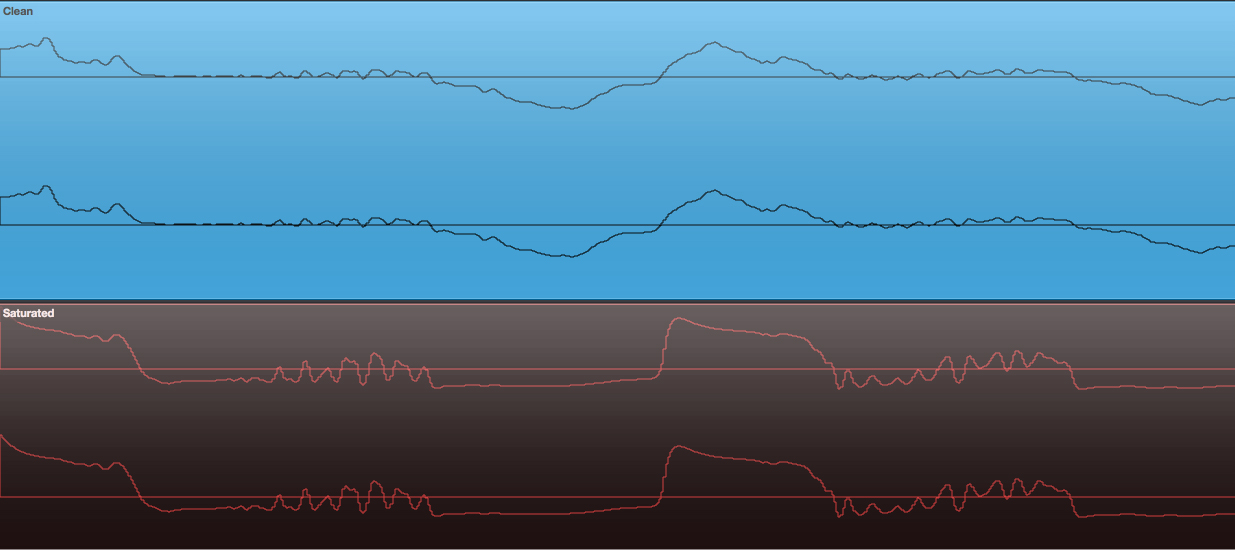

Nuendo continues that support while adding a number of new features ideal for game mixing or sound design. For instance, there’s a Doppler plug-in, which simulates the Doppler Effect: the change in pitch of a sound when a fast-moving object goes past a stationary listener. (The classic example is the sound of a police car, fire truck or ambulance siren as the vehicle drives by.) It’s one of the more difficult audio phenomena to replicate artificially, but this plug-in not only does so with superb accuracy, it also allows you to adjust the start and end positions of the sound as well as the position of the listener, opening up a world of sonic possibilities.

Another Nuendo plug-in that’s handy for gaming sound design is VoiceDesigner. This powerful creative tool offers an array of parameters you can adjust to alter a vocal recording in a myriad of ways, such as morphing it with the vocal characteristics of another voice. For example, if you were creating a monster voice for a game, you could take a recording of a human voice and morph its characteristics with that of a lion or a bear.

There’s little doubt that the field of immersive audio will continue to grow in the years ahead, making it ever more critical for audio engineers and recording musicians to keep up with these changing technologies. So what are you waiting for? It’s time to conquer the complexities of mixing for VR and gaming so you can let your creativity bloom.

Click here for more information about Steinberg Nuendo.