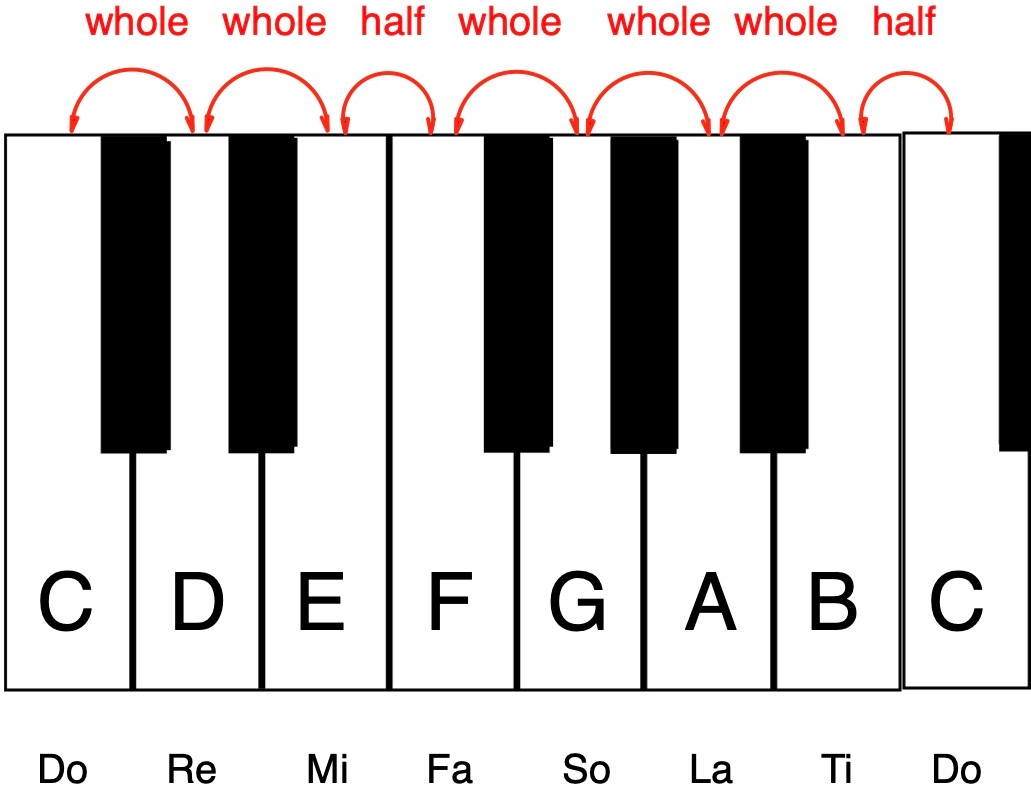

Major and minor scales and arpeggios are some of the simplest and most useful music patterns and exercises available to pianists to build and maintain their technique.

Moreover, these patterns are the building blocks of all tonal music, so practicing them not only helps develop technical facility at the keyboard, it also helps to train our ears to listen critically and our fingers to respond accordingly.

For example, learning to listen for, recognize and then find that raised leading tone on the keyboard in a harmonic minor scale is developed through scale practice. Practicing scales and arpeggios also helps to improve students’ ability to sight-read fluently because their kinesthetic and topographical familiarity with the keyboard is enhanced through the practice of these patterns. In addition, familiarity with scale and broken chord constructions enriches the pianist’s theoretical and analytical understanding of music.

As a high school student, my piano technique was admittedly underdeveloped. While learning a piano sonata by Haydn, I struggled to play the scale passages within the piece with rhythmic evenness and technical control, and I couldn’t figure out how to fix the problem.

Just before the winter break, my piano teacher offhandedly commented that “two hours of scale and arpeggio practice a day will fix those passages and go a long way to improve your technical facility in general.” Young and impressionable, I took this advice literally and spent my winter vacation diligently practicing scales and arpeggios for two hours each day.

Unsurprisingly, my piano technique did improve and my Haydn sonata started to sound better! In addition to my committed practice, my teacher also offered several suggestions for improving my physical approach to technique. These insights together with my dedicated scale practice were vital to improving my scale playing, and my playing in general.

So, while scale and arpeggio practice can be highly beneficial, it is all too common for students to play these patterns without considering their physical approach to the keyboard. If their approach is unhealthy, technical progress can be slow or even thwarted. Teaching a student to find and maintain a healthy hand position including correct finger action that facilitates rhythmically even, fluid, lucid and musically played scales and arpeggios can be challenging.

Students can develop any number of errors or bad habits in their physical approach to the keyboard, playing position and motion across the keys, and these poor habits can be challenging to correct later on. Some of the most common errors in the physical approach to playing scales and arpeggios include:

Most worryingly, these poor physical habits may result in inefficient technique, uneven and unmusical scale and arpeggio playing, and even injury. Below, I have considered each of these common errors and provided some teaching suggestions for improvement.

Fix It: Flat or Curled Fingers

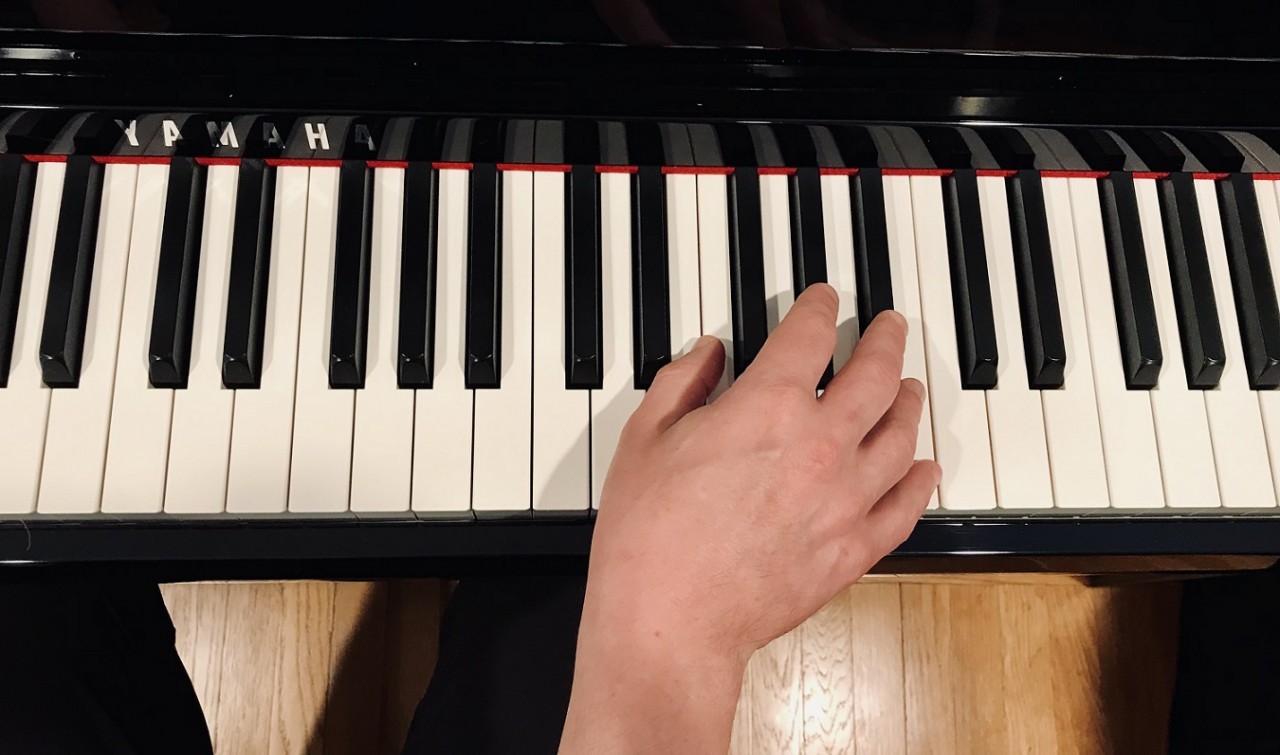

Students often play with flat fingers — with their nails visible on the keys — so they can see that they are playing the desired keys. However, a curved hand position where the tips of the fingers are used allows for more dexterous scale playing because the fingers are able to move with greater ease and speed. The fingers simply cannot move as quickly in a flattened position. When playing with flat fingers, there is also more friction between the fingers and the keys, which makes it difficult to play scales fast. Think of flat-fingered scale playing as akin to sprinting flat footed.

Students often play with flat fingers — with their nails visible on the keys — so they can see that they are playing the desired keys. However, a curved hand position where the tips of the fingers are used allows for more dexterous scale playing because the fingers are able to move with greater ease and speed. The fingers simply cannot move as quickly in a flattened position. When playing with flat fingers, there is also more friction between the fingers and the keys, which makes it difficult to play scales fast. Think of flat-fingered scale playing as akin to sprinting flat footed.

On the other end of the spectrum, students may overdo curved hand positions and end up curling their fingers. As such, they grip the keys and play with what some teachers call “the claw.” Playing scales in this way necessitates a lot of physical effort as one muscle or set of muscles is needed to keep the fingers in this curled position, while another muscle or set is needed to lift and move the fingers.

On the other end of the spectrum, students may overdo curved hand positions and end up curling their fingers. As such, they grip the keys and play with what some teachers call “the claw.” Playing scales in this way necessitates a lot of physical effort as one muscle or set of muscles is needed to keep the fingers in this curled position, while another muscle or set is needed to lift and move the fingers.

In the article, “Pianist’s Injuries,” Thomas Mark writes: “When one muscle contracts, the opposing muscle must release and lengthen to permit movement. If this does not happen — that is, if the opposing muscle remains tense — then both muscles are contracting simultaneously, which is called co-contraction.” This idea of co-contraction not only causes tension and inhibits the player’s ability to play scales and arpeggios quickly, evenly and efficiently, it can also lead to serious injury. Thomas Mark’s book, “What Every Pianist Should Know About the Body” is an invaluable resource to all pianists and teachers.

SOLUTION: The solution to correcting flat or curled fingers is similar. First, help your students understand that neither flat nor curled fingers are the most comfortable or ideal finger position for fast scale playing. In a neutral position, the fingers of the hand curve naturally, and this position is best for achieving superior scale and arpeggio playing. Here’s a simple exercise to help students find the natural curve of the fingers: Have them lift their arms to shoulder height at their sides and then drop their arms freely. Looking down, they will notice that their fingers are now in a naturally curved position.

SOLUTION: The solution to correcting flat or curled fingers is similar. First, help your students understand that neither flat nor curled fingers are the most comfortable or ideal finger position for fast scale playing. In a neutral position, the fingers of the hand curve naturally, and this position is best for achieving superior scale and arpeggio playing. Here’s a simple exercise to help students find the natural curve of the fingers: Have them lift their arms to shoulder height at their sides and then drop their arms freely. Looking down, they will notice that their fingers are now in a naturally curved position.

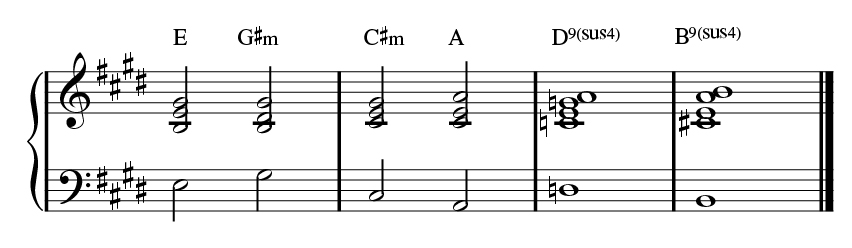

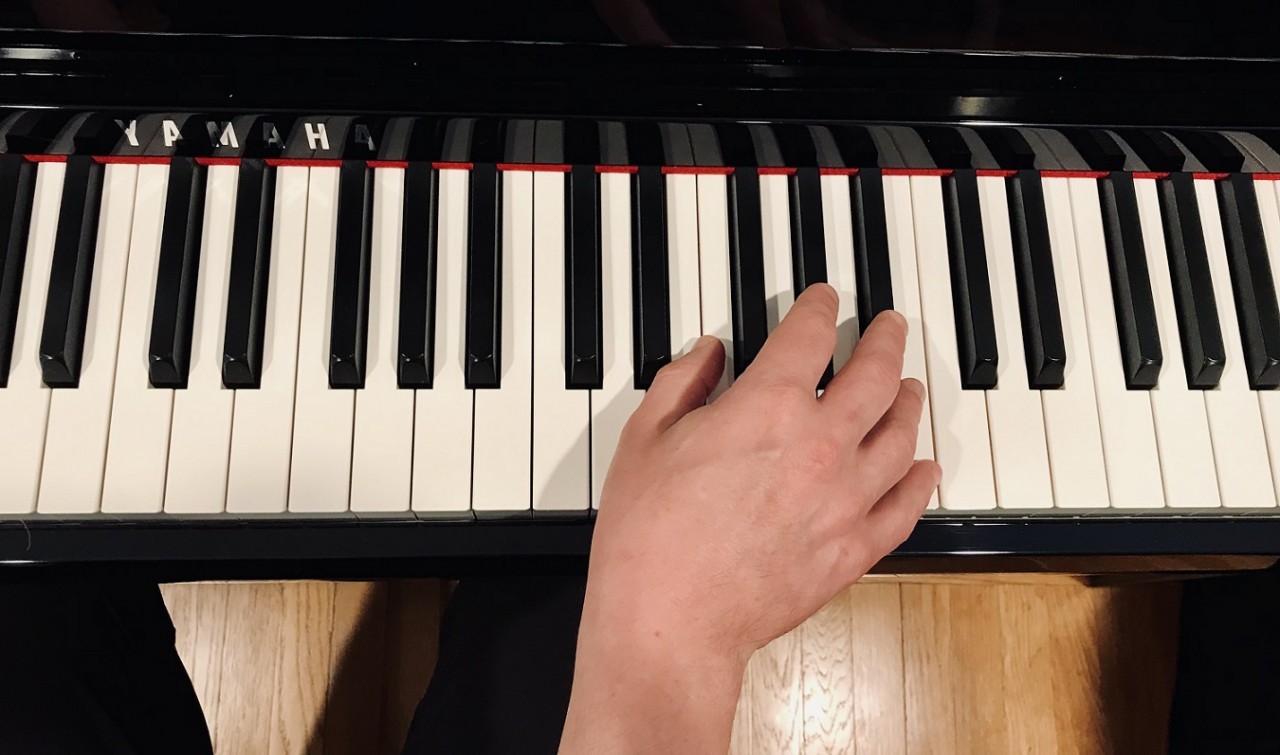

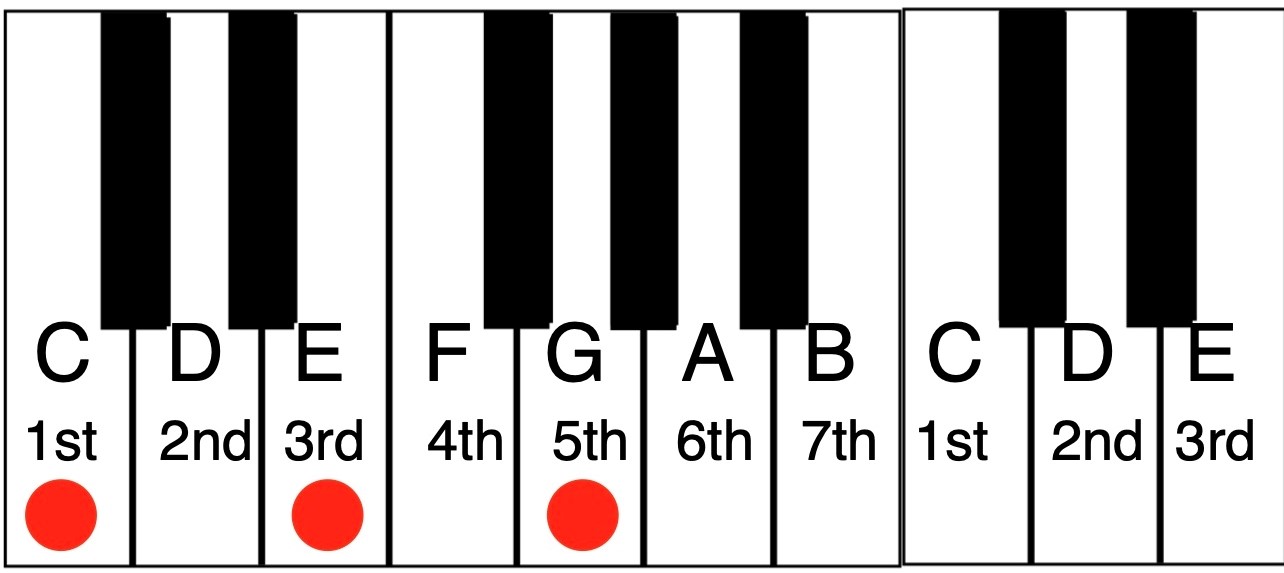

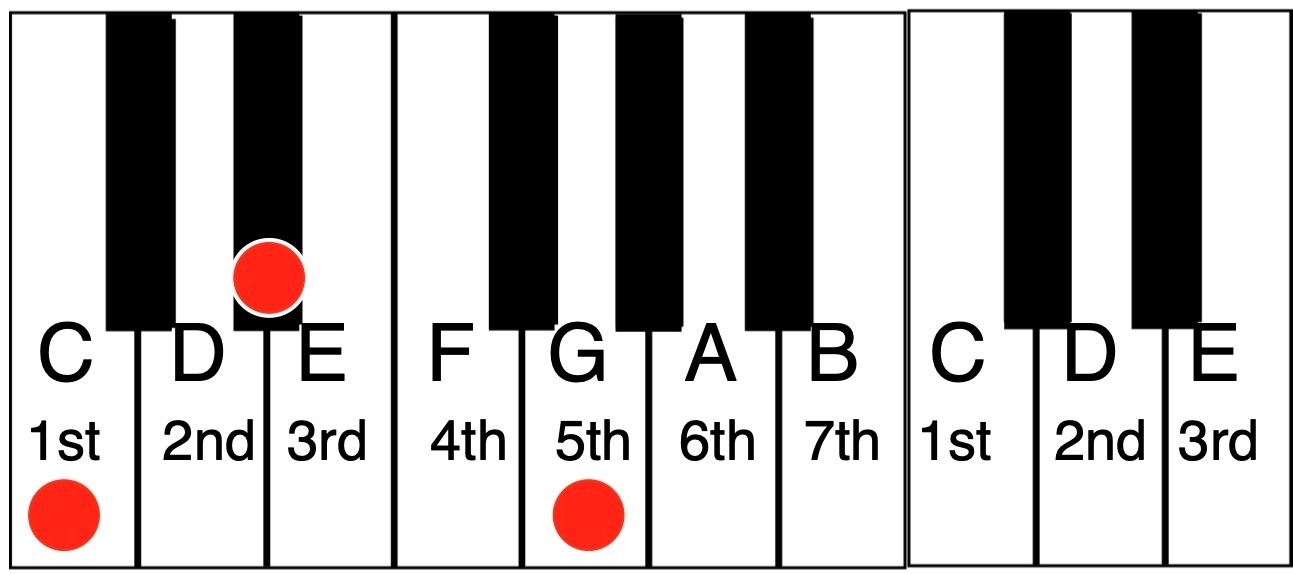

In the book, “Chopin: Pianist and Teacher as Seen by His Pupils,” Chopin’s advice for finding good hand shape on the keyboard was to place the right-hand thumb on E, the longer fingers 2, 3 and 4 on the group of three black keys, and finger 5 on B (or C for a larger hand). The mirror image works for the left hand (thumb on B and 5th finger on E/F with fingers 2, 3 and 4 on the black keys). Teachers can then adjust this position as needed. Take a picture of this proper hand position and send it to your students, so they can refer to it during future practice sessions.

THE YAMAHA EDUCATOR NEWSLETTER: Join to receive a round-up of our latest articles and programs!

Fix It: Incorrect Thumb Position and Motion

Many students misunderstand the correct position of the thumb on the keys and try to play using too much of the thumb, or even attempt to play on the very tip of the distal phalanx rather than on the corner of it (the spot on each thumb where the nail meets flesh). As such, students sometimes incorrectly play with a straight rather than a slightly bent thumb.

Many students misunderstand the correct position of the thumb on the keys and try to play using too much of the thumb, or even attempt to play on the very tip of the distal phalanx rather than on the corner of it (the spot on each thumb where the nail meets flesh). As such, students sometimes incorrectly play with a straight rather than a slightly bent thumb.

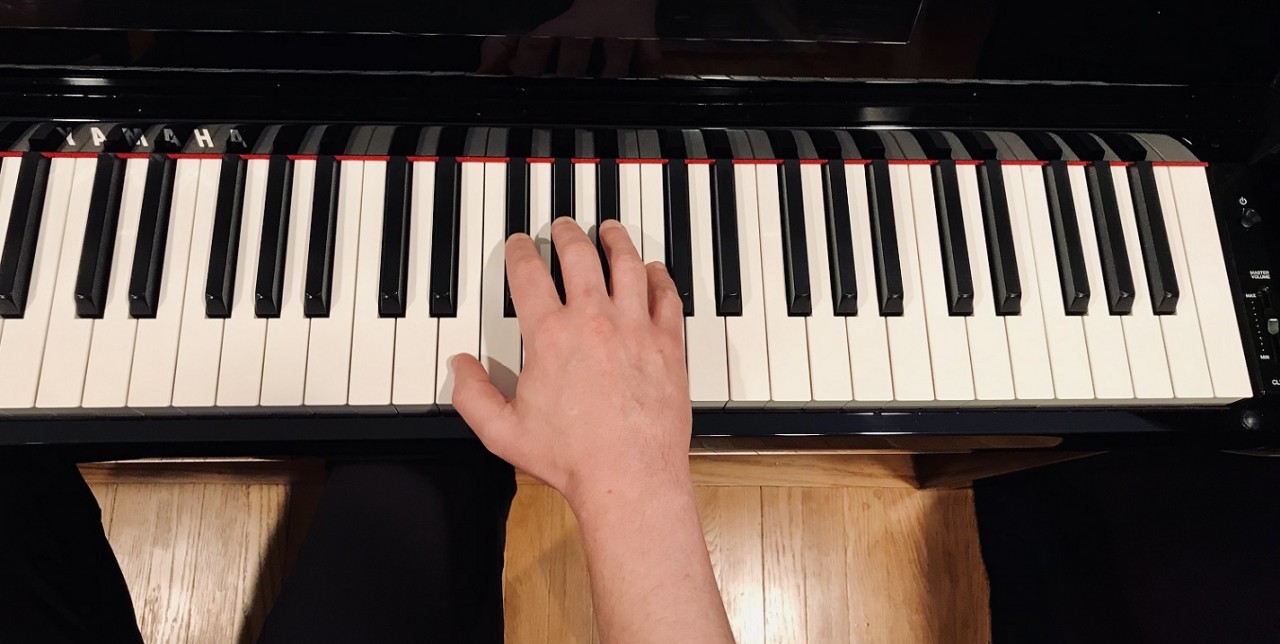

In addition, when passing the thumb in ascending right-hand and descending left-hand scales or arpeggios, many students begin moving the thumb under the hand too late, or keep the thumb straight rather than slightly bent at the proximal interphalangeal joint when moving it.

In addition, when passing the thumb in ascending right-hand and descending left-hand scales or arpeggios, many students begin moving the thumb under the hand too late, or keep the thumb straight rather than slightly bent at the proximal interphalangeal joint when moving it.

These errors can result in a bump in sound or “lumpy thumb” patterns and jerky movements as the student struggles to move the thumb with ease and on time. The bump often happens because the thumb is moving with speed to play in time. As such, the key played by the thumb is played faster and the resulting tone is louder — i.e., a “bumped” note and a scale that sounds tonally uneven. Alternatively, some students drop the entire forearm when passing the thumb under the hand as they play on the incorrect part of the thumb or try to play with the thumb at the wrong angle, and thereby create a thumb “bump” or accent at every hand position change in scale or arpeggio playing.

SOLUTION: The best way to help a student understand where to play on the thumb is to simply point it out to them — touch the part of thumb that should make contact with the key. If a student has been playing with the wrong part of their thumb, or without bending it from the proximal interphalangeal joint, or at the wrong angle in relation to the key, the correct procedure will feel strange and unfamiliar to them. It will take time for them to change their habit and learn to use the thumb properly and effectively.

SOLUTION: The best way to help a student understand where to play on the thumb is to simply point it out to them — touch the part of thumb that should make contact with the key. If a student has been playing with the wrong part of their thumb, or without bending it from the proximal interphalangeal joint, or at the wrong angle in relation to the key, the correct procedure will feel strange and unfamiliar to them. It will take time for them to change their habit and learn to use the thumb properly and effectively.

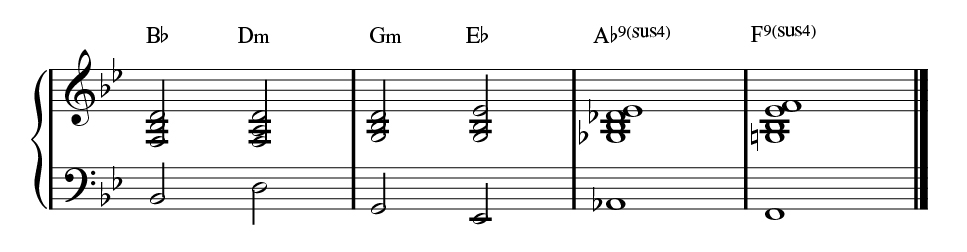

To facilitate improved thumb motion under the hand in scale and arpeggio playing, break down this small, but surprisingly challenging, movement into several steps. I recommend working on this motion first in scale playing versus arpeggios and start with a scale with many black keys. According to the book, “Chopin: Pianist and Teacher as Seen by His Pupils,” Chopin advocated for having students start with B major (right hand) and then D flat major (left hand) scales with the position of the thumb in mind. These are also some of the easiest scales to coordinate in hands-together playing as the thumbs of each hand come together on the white keys. Together with G flat major, these are the first octave scales I teach a student to play hands together. These scales are also excellent for achieving good passing of the thumbs as fingers 2, 3 and 4 play black keys, which are raised, allowing for a natural space to emerge on the keyboard in which the thumb can move freely and easily.

To facilitate improved thumb motion under the hand in scale and arpeggio playing, break down this small, but surprisingly challenging, movement into several steps. I recommend working on this motion first in scale playing versus arpeggios and start with a scale with many black keys. According to the book, “Chopin: Pianist and Teacher as Seen by His Pupils,” Chopin advocated for having students start with B major (right hand) and then D flat major (left hand) scales with the position of the thumb in mind. These are also some of the easiest scales to coordinate in hands-together playing as the thumbs of each hand come together on the white keys. Together with G flat major, these are the first octave scales I teach a student to play hands together. These scales are also excellent for achieving good passing of the thumbs as fingers 2, 3 and 4 play black keys, which are raised, allowing for a natural space to emerge on the keyboard in which the thumb can move freely and easily.

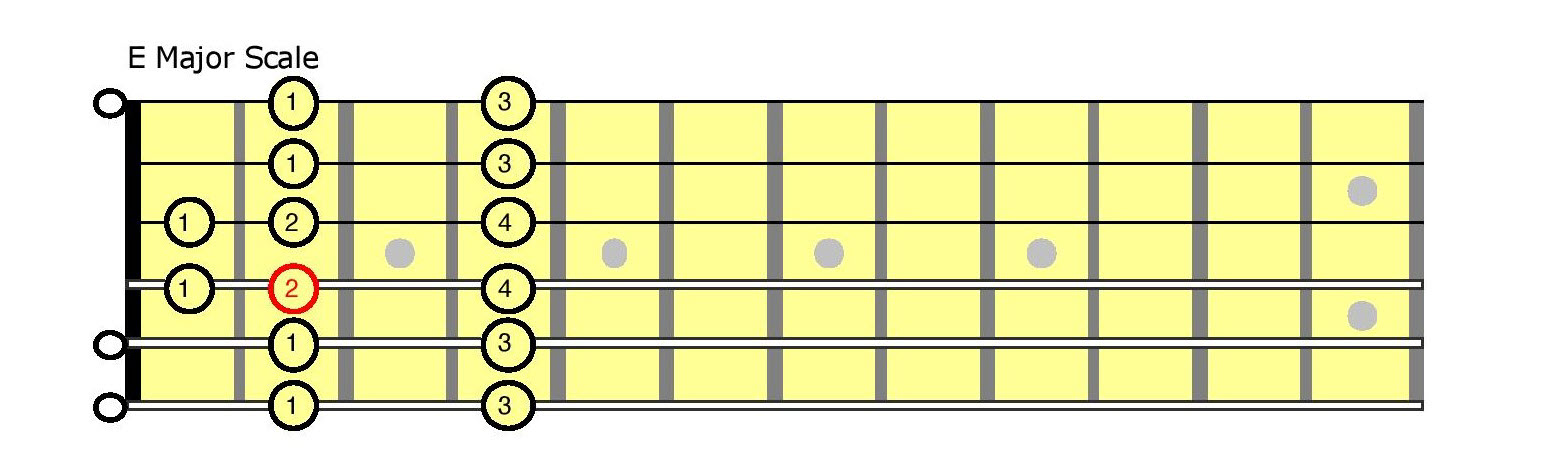

The C major scale is the hardest to play with the passing of the thumb in mind as there are no black keys. As a result, it was the last scale Chopin apparently used to teach to his students and is the last scale I teach as well. Of the scales starting on a white key with the same fingering as C major in both hands, E major is physically easiest to play, in my opinion, as it has four black keys.

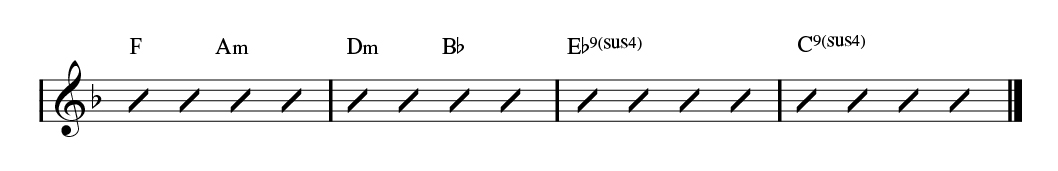

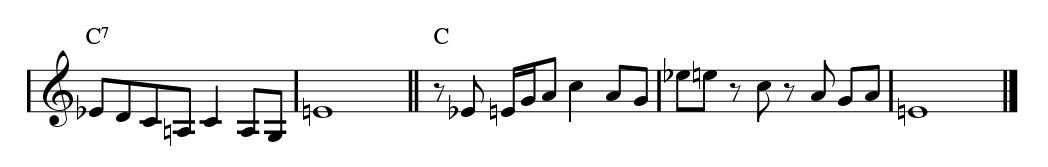

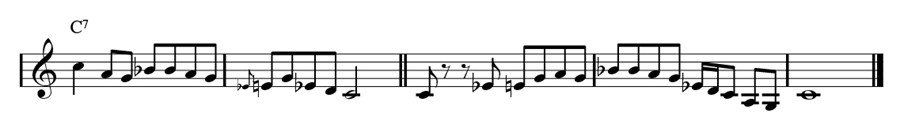

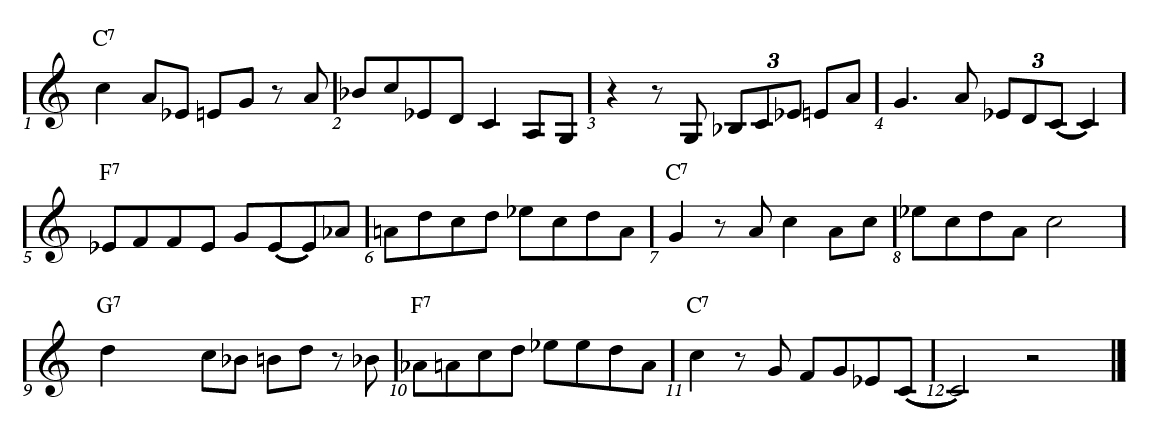

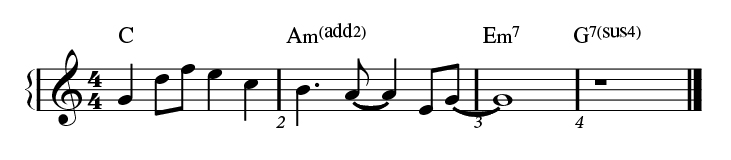

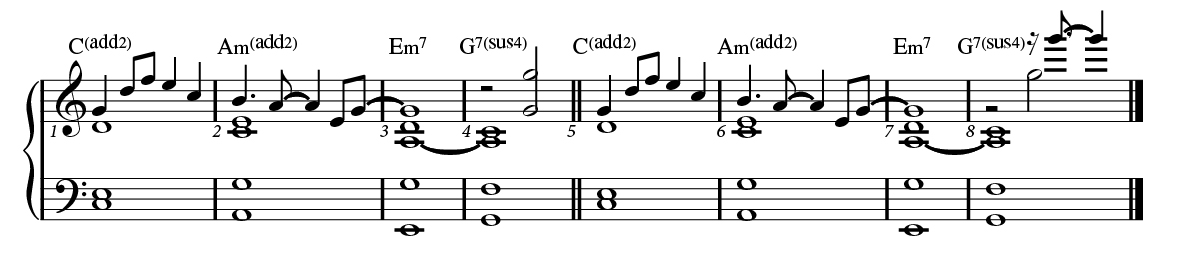

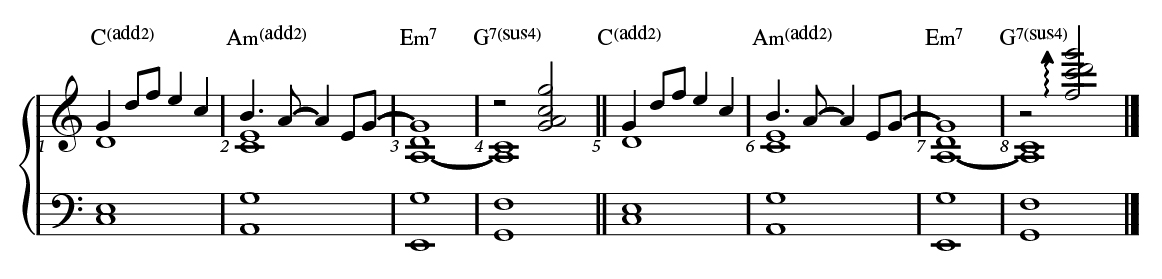

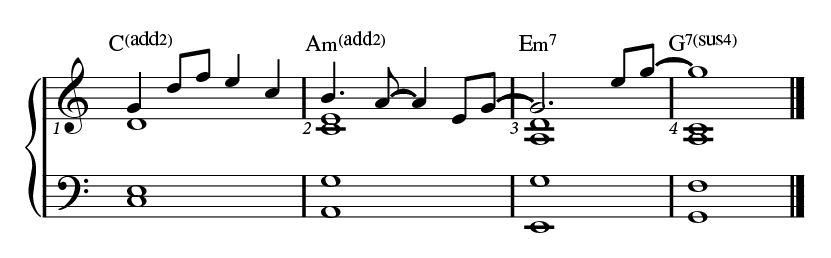

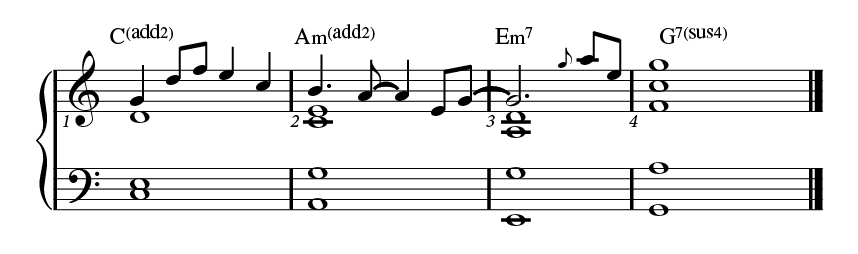

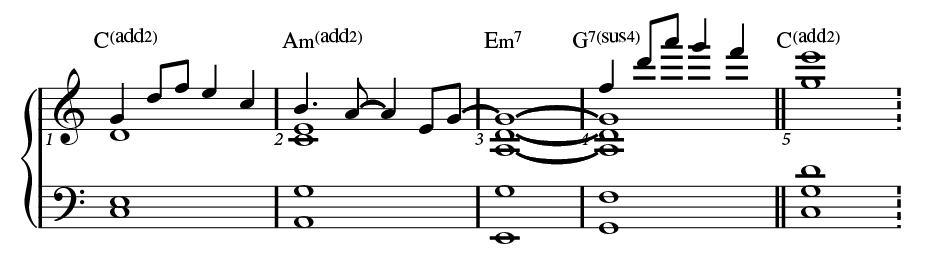

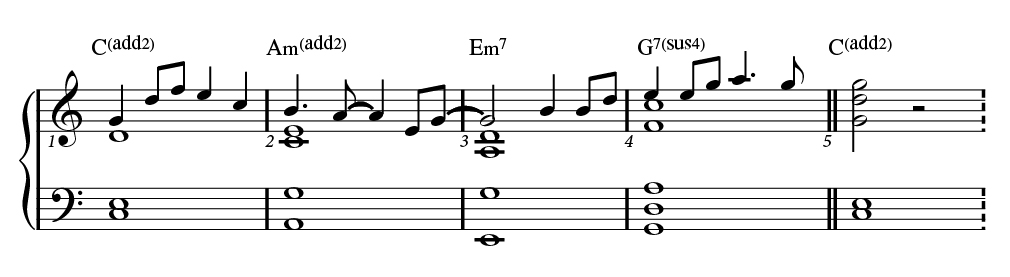

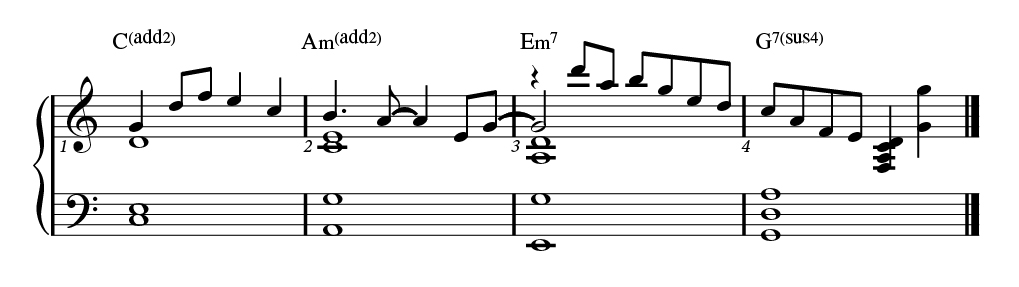

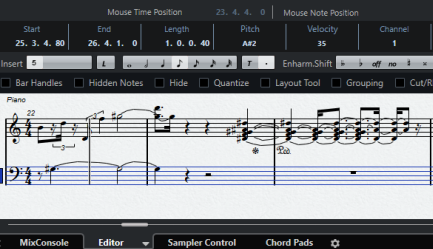

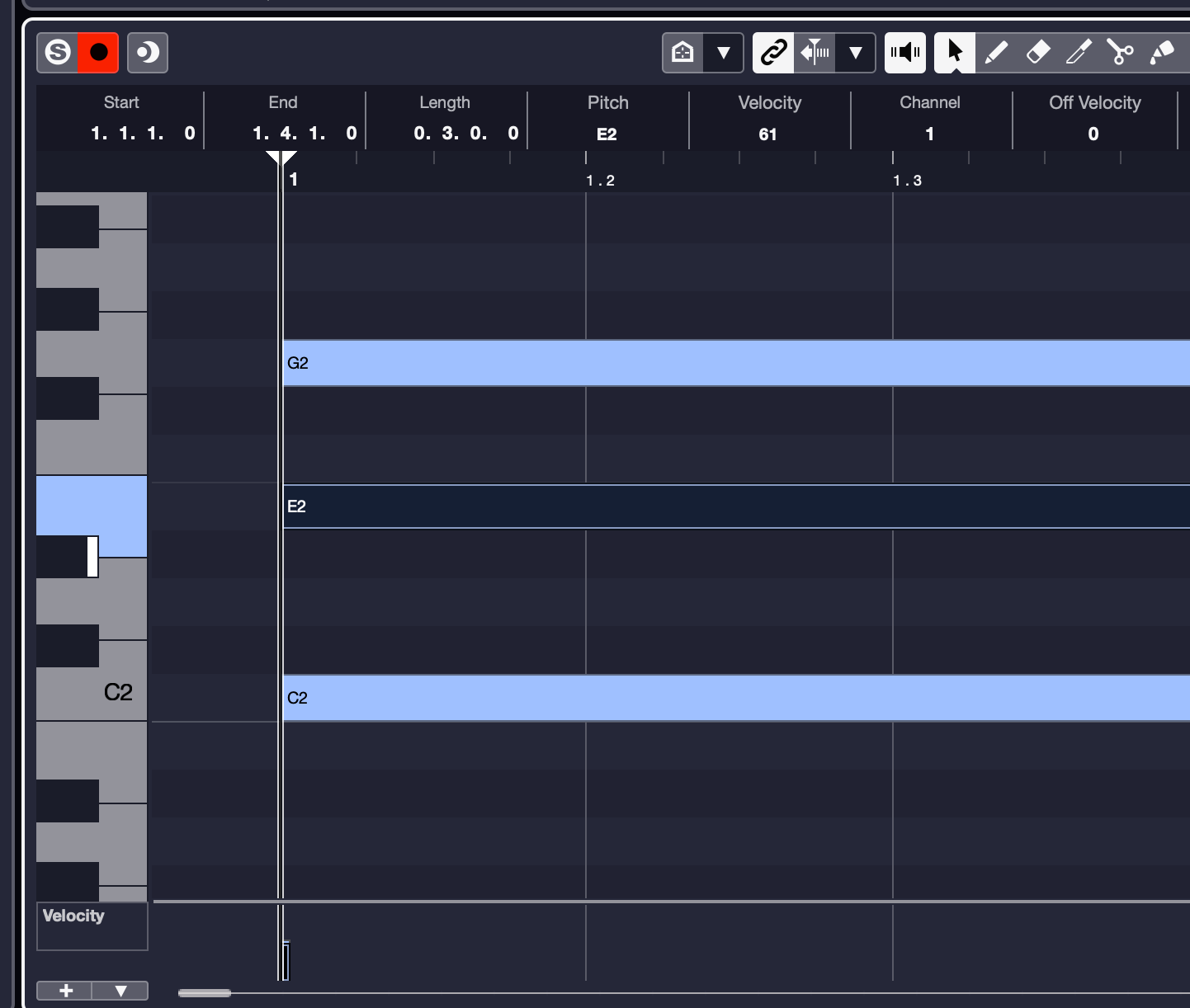

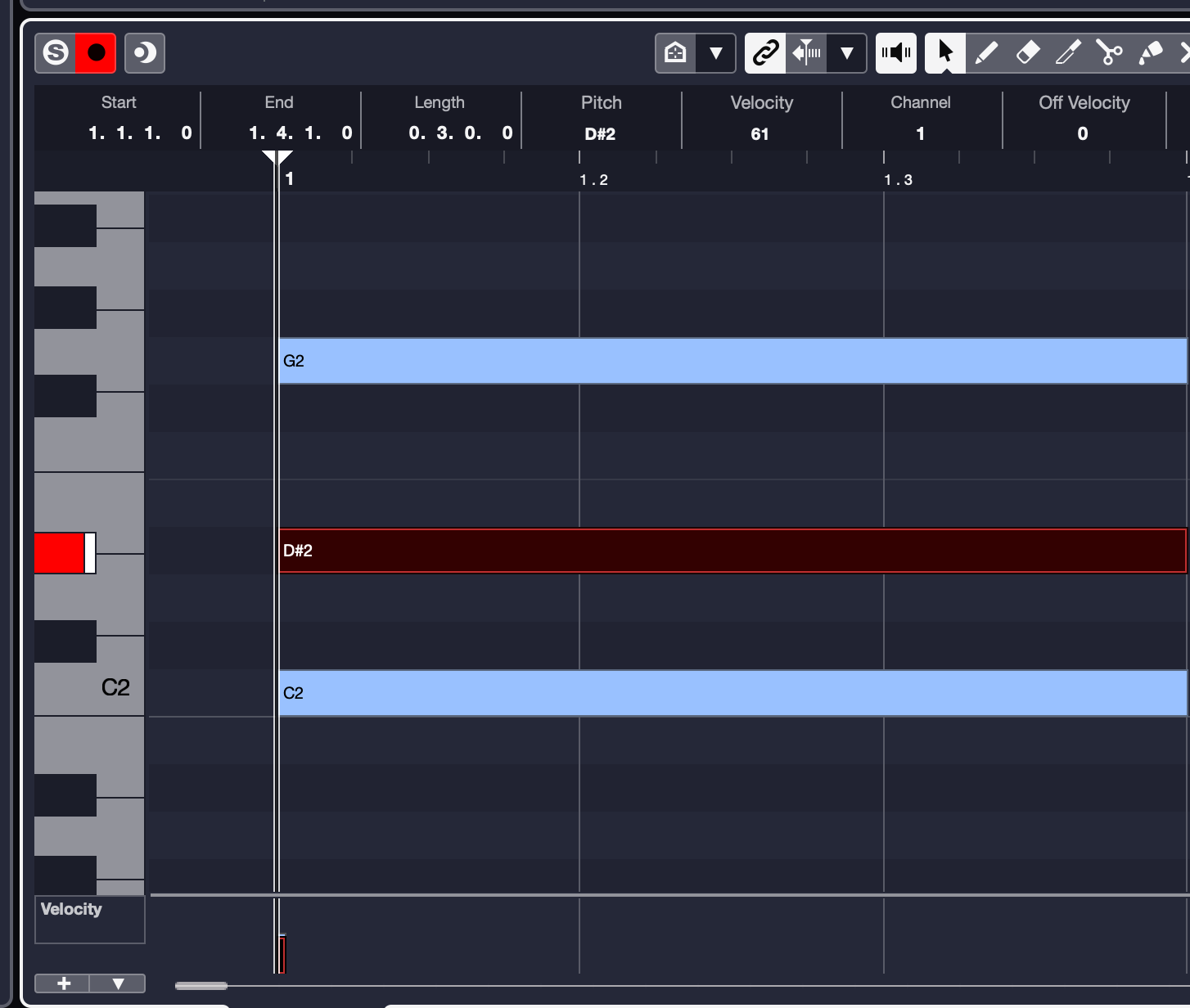

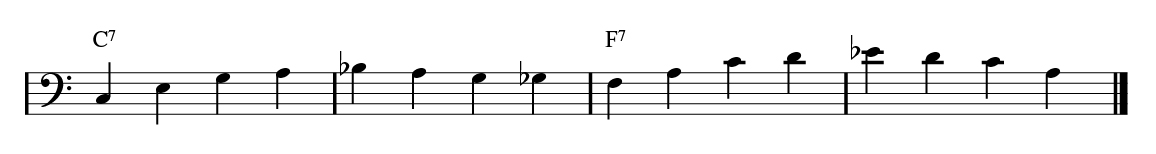

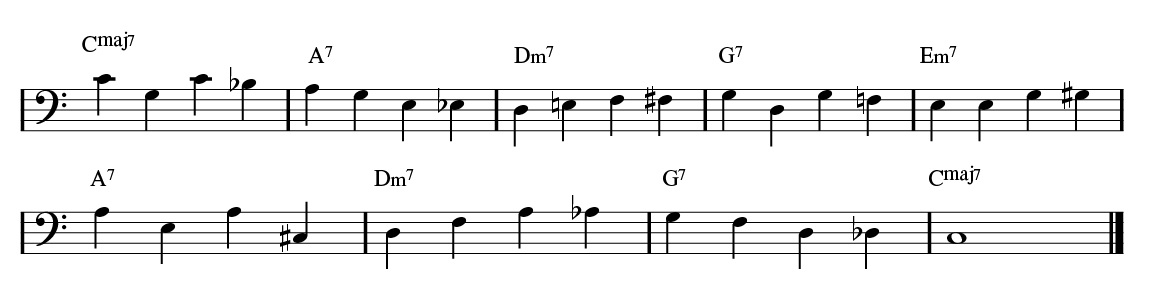

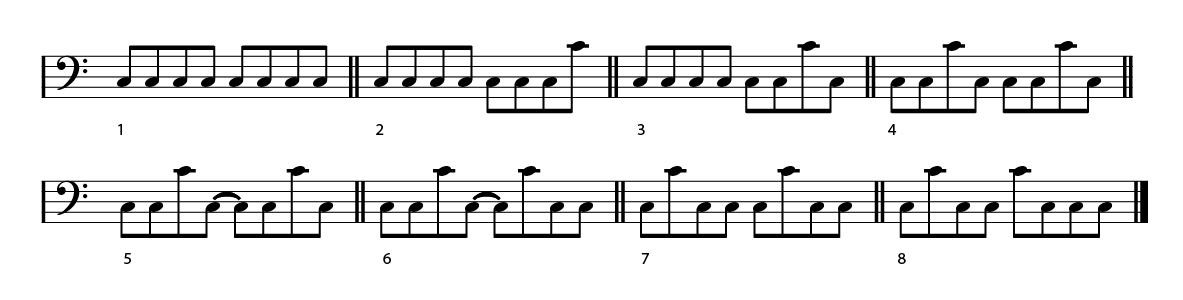

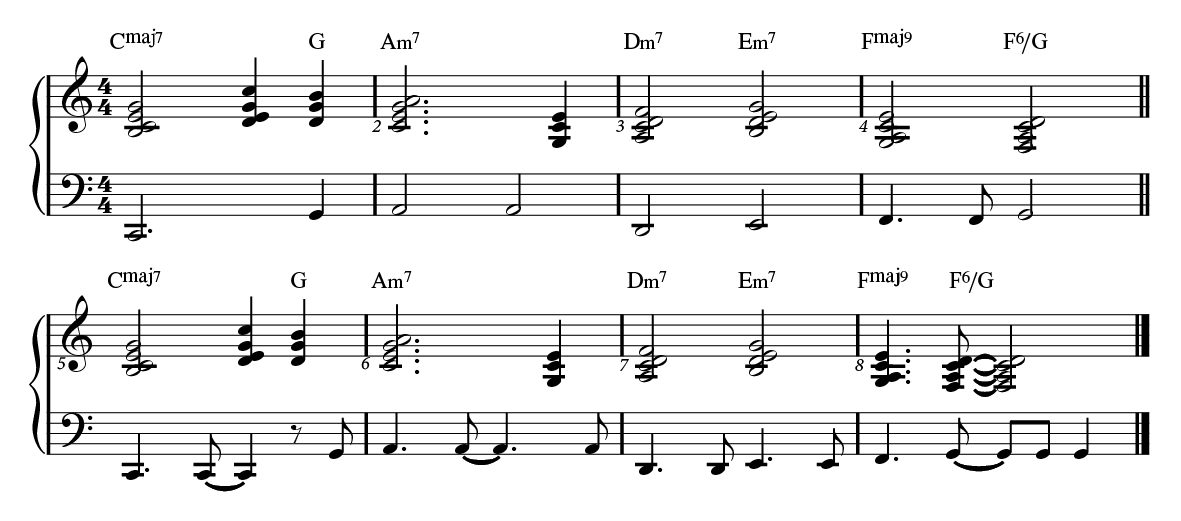

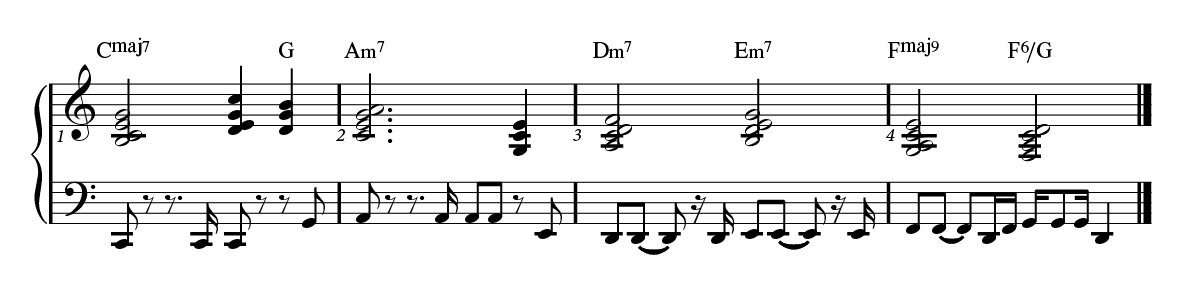

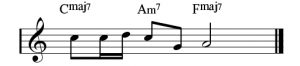

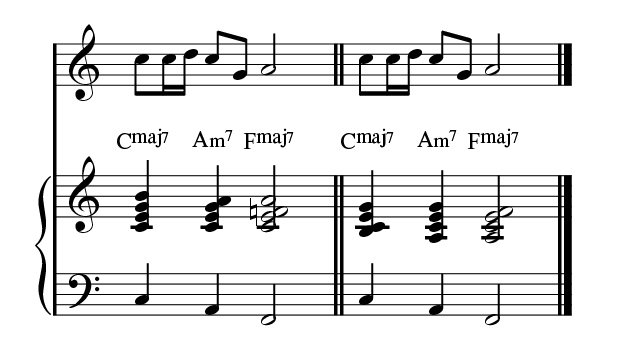

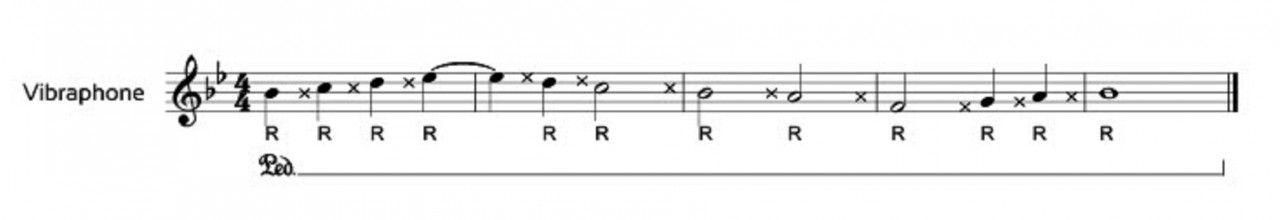

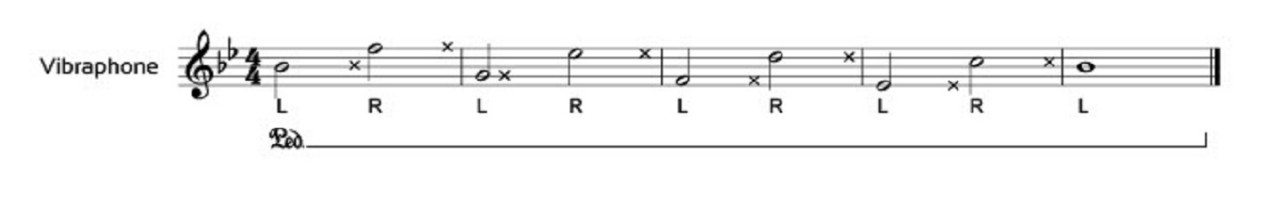

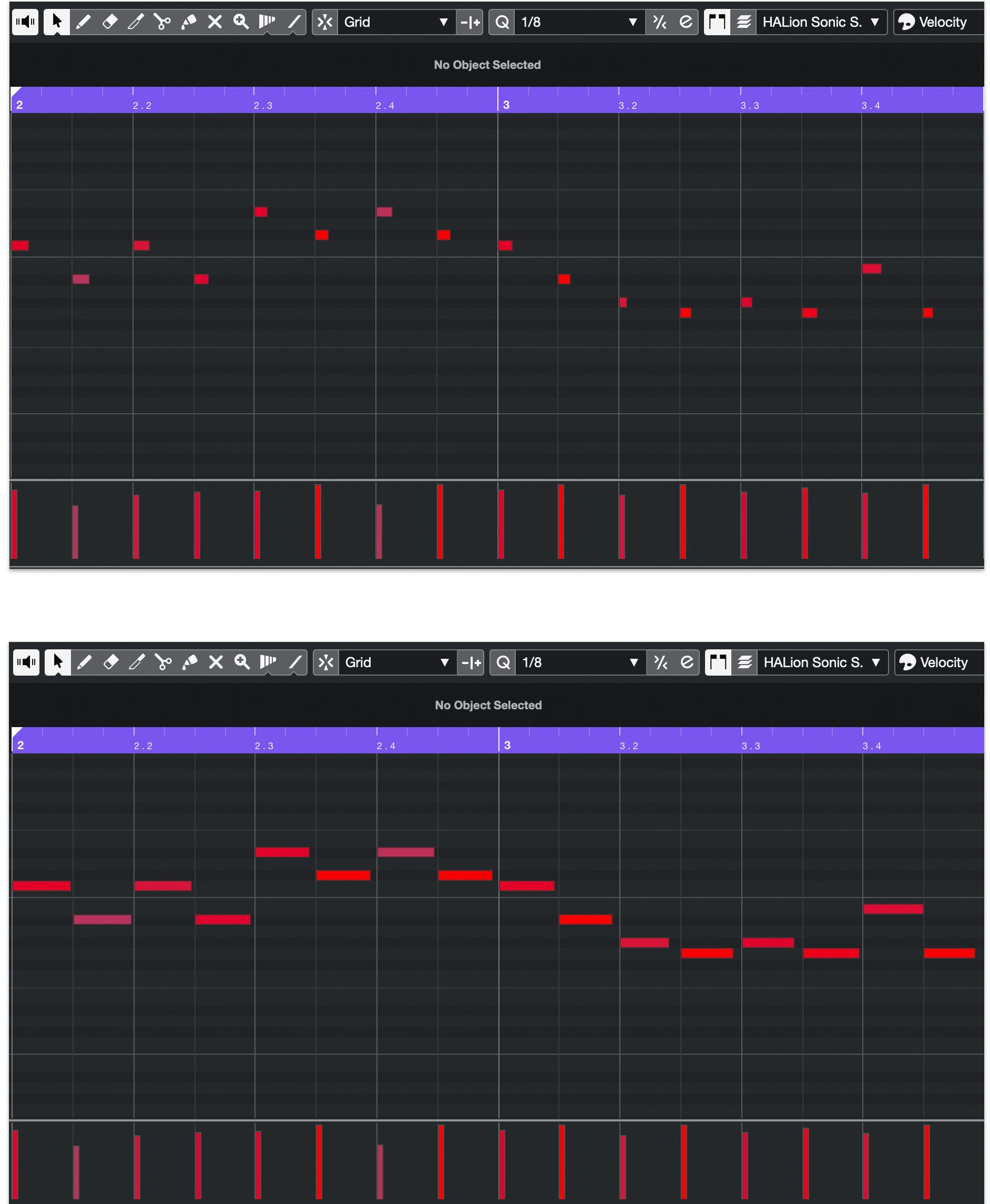

For my sample exercise below, which is demonstrated in this video, I have referenced the E major scale, ascending in the right hand and descending in the left hand as follows:

- Tell students to get ready to play the first three notes of the scale: E, F sharp and G sharp in sequence with fingers 1, 2 and 3 on the right hand or E, D sharp and C sharp on the left hand.

- As soon as the thumb has finished playing the E, tuck it under the hand.

- To help facilitate a bending motion of the thumb, brush/touch the inside of the hand, just below the fourth or third finger.

- Teachers must ensure that the student uses the motion of the arm to help prepare the hand position change and that the wrist is high enough (but not too high) to facilitate the passing under motion of the thumb.

- Then have students play A with the right-hand thumb or B with the left-hand thumb. Thereafter, go back and forth playing these first four notes of the scale ascending and then descending with the right hand (and vice versa with the left hand) until the thumb is moving optimally, and the wrist, arm and hand are helping to facilitate a smooth and efficient thumb movement and hand position change.

Fix It: Suboptimal Wrist Position

Some students try to play scales with a hand(s) that is not kept in line with the arm at the wrist, such that the position of the wrist joint is overly high or overly low.

Some students try to play scales with a hand(s) that is not kept in line with the arm at the wrist, such that the position of the wrist joint is overly high or overly low.

In his article, “Pianist’s Injuries” on pianomap.com, Thomas Mark calls these “awkward positions” and states that,“the mid-range position of the wrist, with the wrist in a straight line with the arm, gives the greatest mechanical advantage to the fingers.”

As such, ease of movement is lost, tension can develop and injury can ensue when utilizing awkward wrist positions while playing.

As such, ease of movement is lost, tension can develop and injury can ensue when utilizing awkward wrist positions while playing.

SOLUTION: An old trick for helping students play with the wrist in a mid-range position is to place a quarter on the wrist. If the coin falls while the student is playing, the wrist has either dropped too low or lifted too high.

Some teachers prefer to use the image of a “floating wrist” to help students achieve an improved mid-range position. When I inherit a student who has been taught to make a dropping motion of the wrist on every finger action to achieve a weighty sounding scale, I encourage them to strive for “beautifully gliding” scales. As such, the arm guides the fingers so that the hands and arms move laterally (or horizontally) over the keys like a figure skater glides effortlessly over a glassy lake, rather than creating the visual and sonic effect of choppy waves. Gliding scales can be further enhanced with a gradual and even crescendo ascending and diminuendo descending. In this way, they are rhythmically even and musically shaped.

Some teachers prefer to use the image of a “floating wrist” to help students achieve an improved mid-range position. When I inherit a student who has been taught to make a dropping motion of the wrist on every finger action to achieve a weighty sounding scale, I encourage them to strive for “beautifully gliding” scales. As such, the arm guides the fingers so that the hands and arms move laterally (or horizontally) over the keys like a figure skater glides effortlessly over a glassy lake, rather than creating the visual and sonic effect of choppy waves. Gliding scales can be further enhanced with a gradual and even crescendo ascending and diminuendo descending. In this way, they are rhythmically even and musically shaped.

Fix It: Collapsing Finger Joints and No Bridge Support

Some students are able to implement the natural curve of the hand in their scale playing, but then they allow the final knuckle or distal interphalangeal joint of fingers 1, 2, 3 and/or 4 to collapse as one or more fingers depress the keys (this happens most often with finger 4, in my experience). According to Carolyn and Jamie Shaak in “The Shaak Technique Book,” all three finger knuckles (metacarpophalangeal, proximal interphalangeal and distal interphalangeal joints) of fingers 1 to 4 should remain “firm and fixed” and not collapse at any point when playing scales or arpeggios.

Some students are able to implement the natural curve of the hand in their scale playing, but then they allow the final knuckle or distal interphalangeal joint of fingers 1, 2, 3 and/or 4 to collapse as one or more fingers depress the keys (this happens most often with finger 4, in my experience). According to Carolyn and Jamie Shaak in “The Shaak Technique Book,” all three finger knuckles (metacarpophalangeal, proximal interphalangeal and distal interphalangeal joints) of fingers 1 to 4 should remain “firm and fixed” and not collapse at any point when playing scales or arpeggios.

Collapsing joints can result in two-handed scale playing in which the hands are unaligned or unsynchronized because the final finger joint in one or both hands is not firm and, therefore, not moving with control, resulting in differing speeds in the dissent of the keys played by each hand.

Collapsing joints can result in two-handed scale playing in which the hands are unaligned or unsynchronized because the final finger joint in one or both hands is not firm and, therefore, not moving with control, resulting in differing speeds in the dissent of the keys played by each hand.

Also common is the lack of knuckle support at the metacarpophalangeal joints within the hand. Strong knuckles are visibly pronounced in piano playing and together form what is sometimes called the “bridge” of the hand. When this so-called bridge is not well developed or implemented in piano playing, it can cause lack of dexterity and clarity of tone, especially when playing scales. It can also cause tension in the hand and lead to injury.

SOLUTION: Collapsing knuckle joints are a bad habit and teachers must be vigilant and tireless in their efforts to correct this bad habit among their students. First, students must be aware of how it feels to use the fingertips correctly versus incorrectly.

SOLUTION: Collapsing knuckle joints are a bad habit and teachers must be vigilant and tireless in their efforts to correct this bad habit among their students. First, students must be aware of how it feels to use the fingertips correctly versus incorrectly.

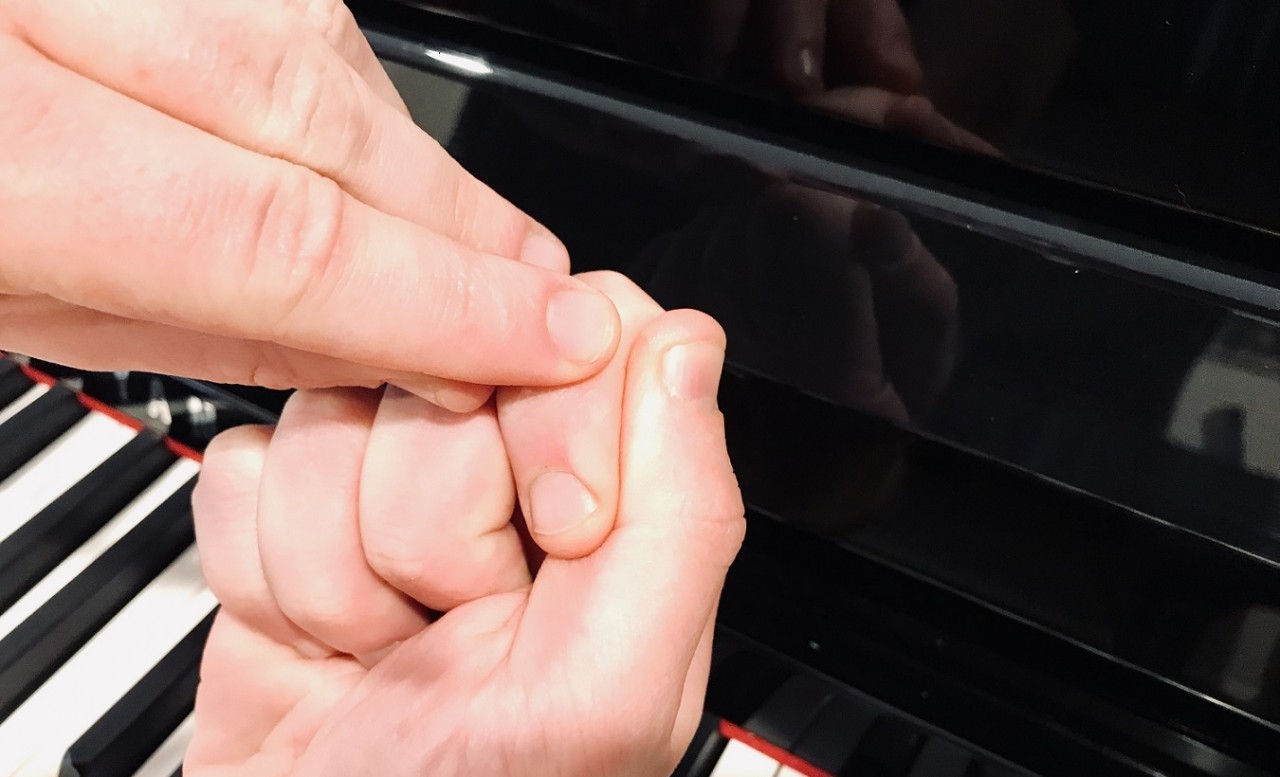

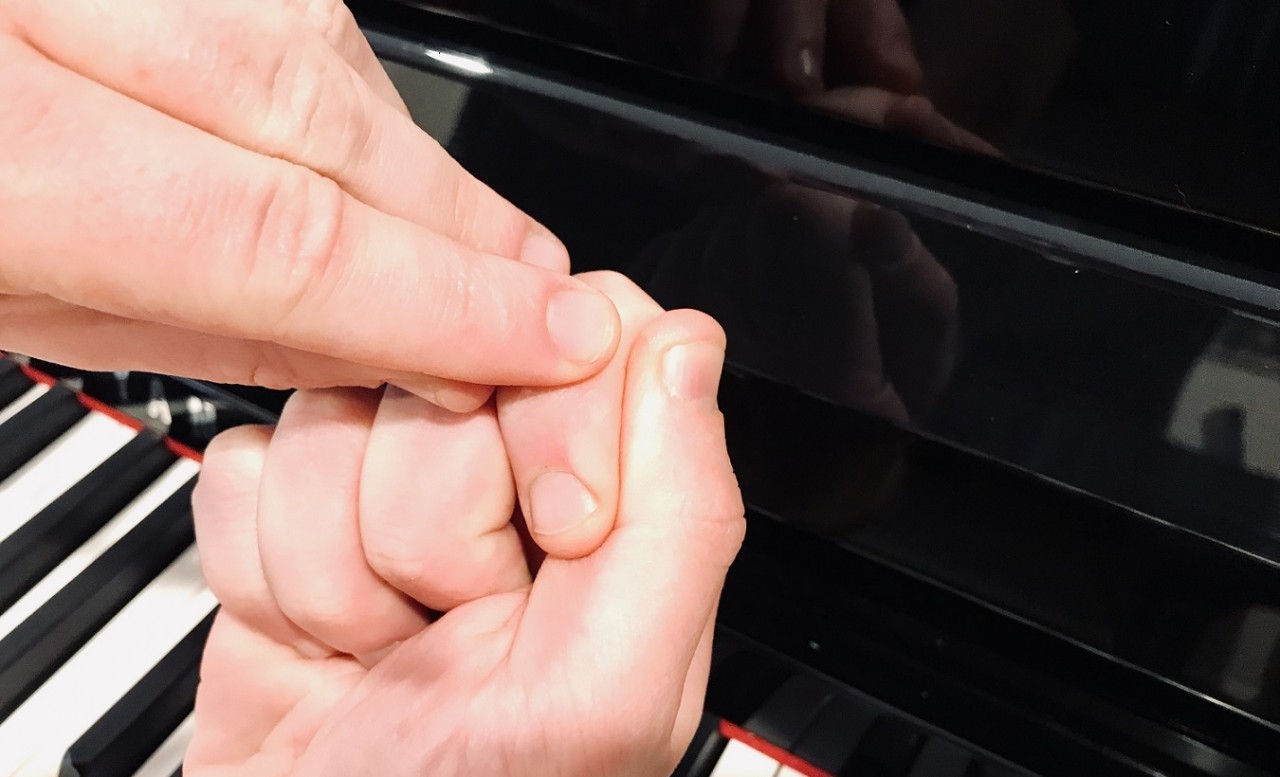

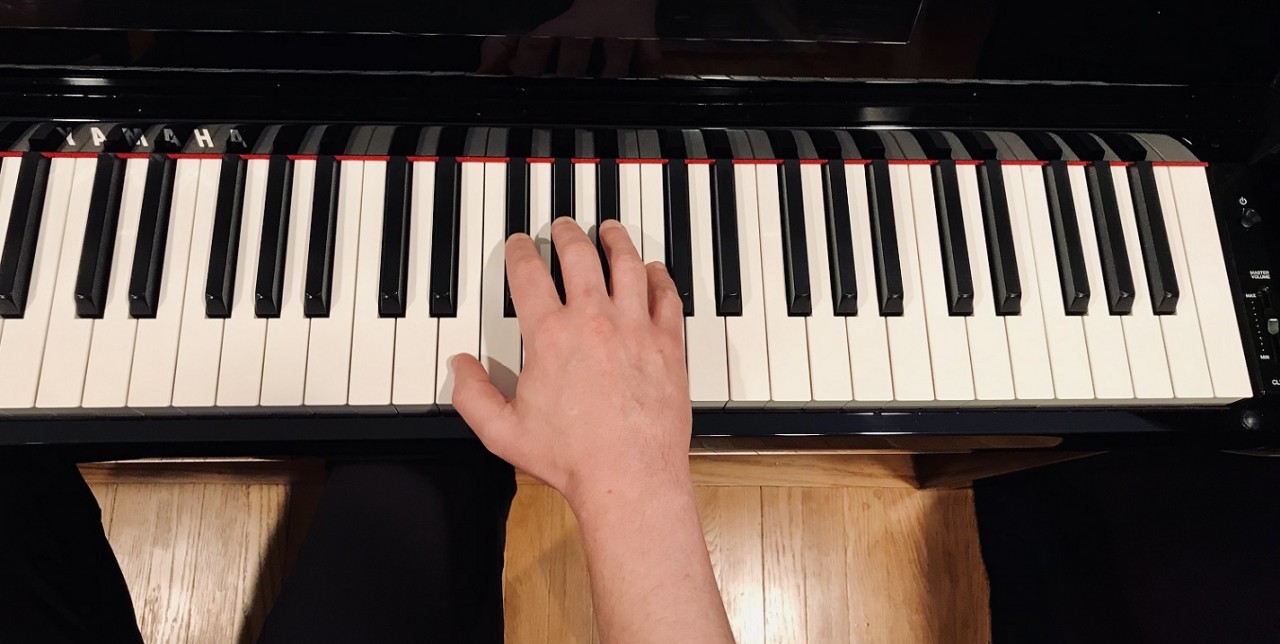

I recommend reading the article, “Synergy at the Primer Level,” by Randall Faber. He describes one way to help students feel the correct part of the fingertip used in piano playing. This is done by having students create an “O” shape (see photo to the right) by placing the thumb behind the final knuckle joint of each of fingers 1 through 4 in turn, thereby reinforcing or “bracing” the part of the fingertip used in piano playing of whichever fingertip needs to be (re)discovered. Students can then take that reinforced fingertip and tap it (or “peck” it) on a tabletop or have it touch/depress a key on the piano. I frequently review this exercise with students when one or more of their fingers show some weakness in the final joint and start to collapse when playing.

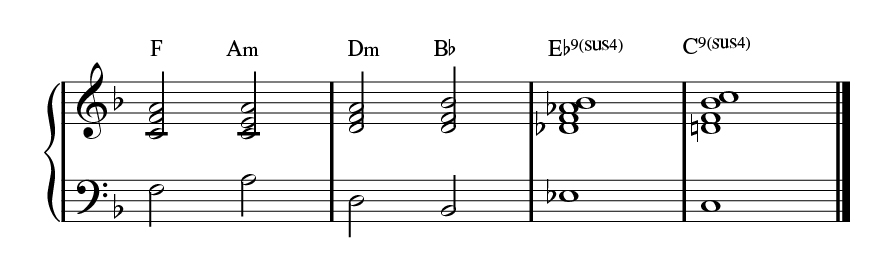

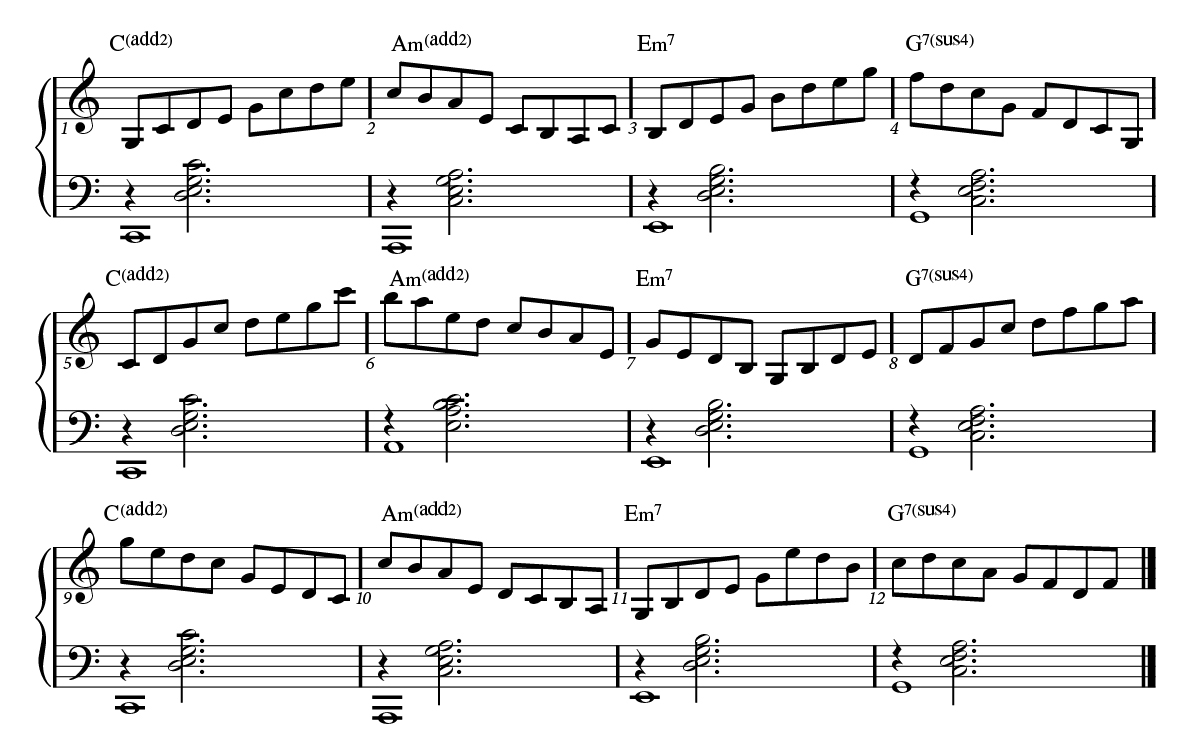

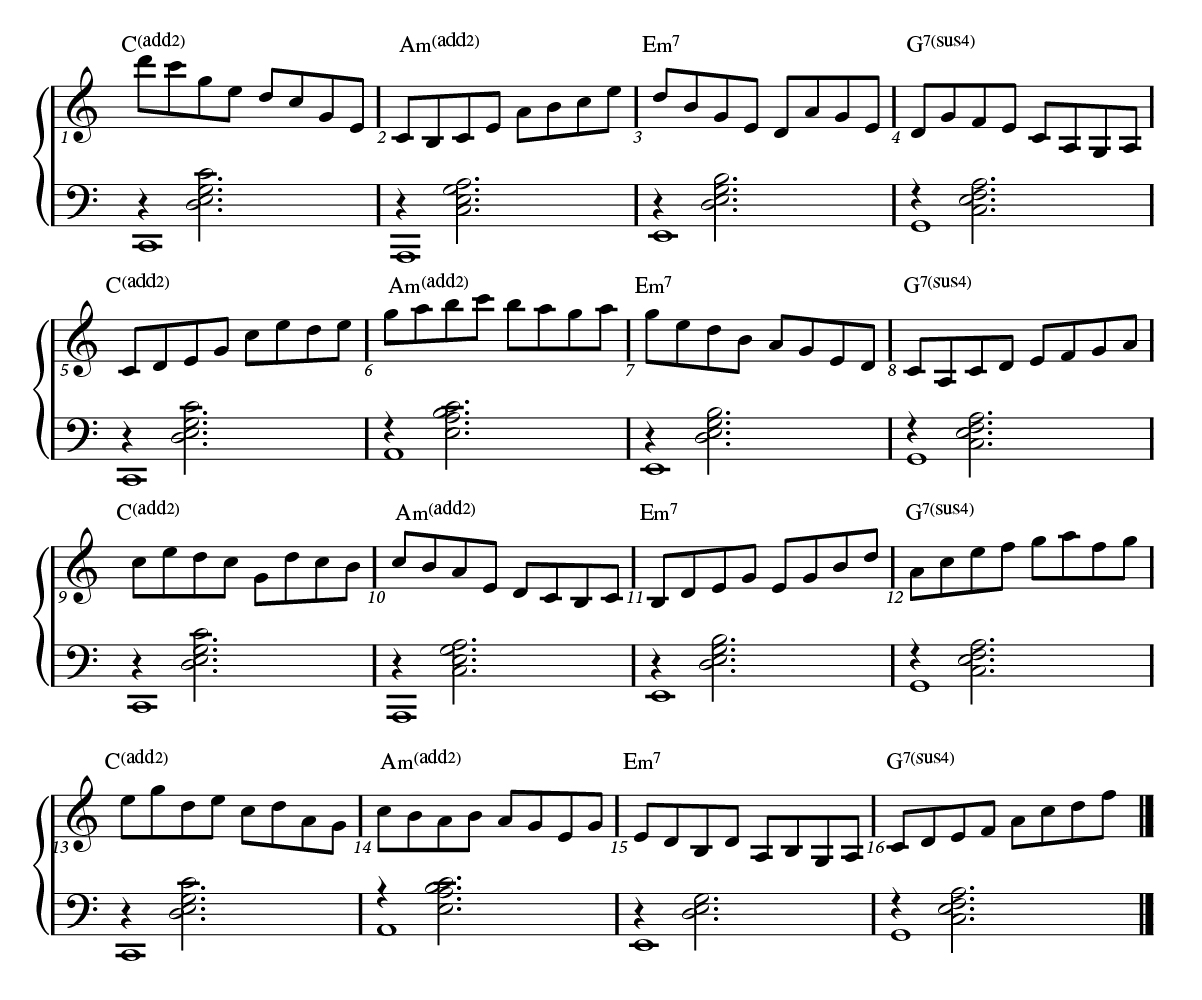

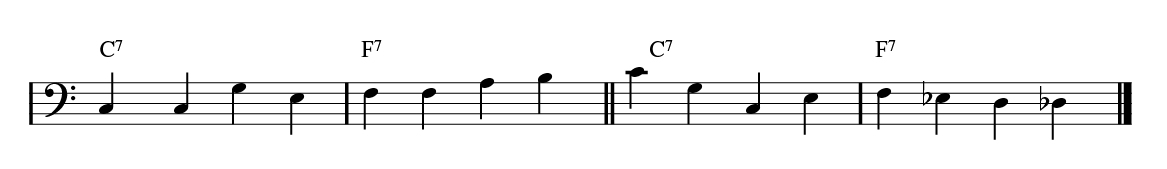

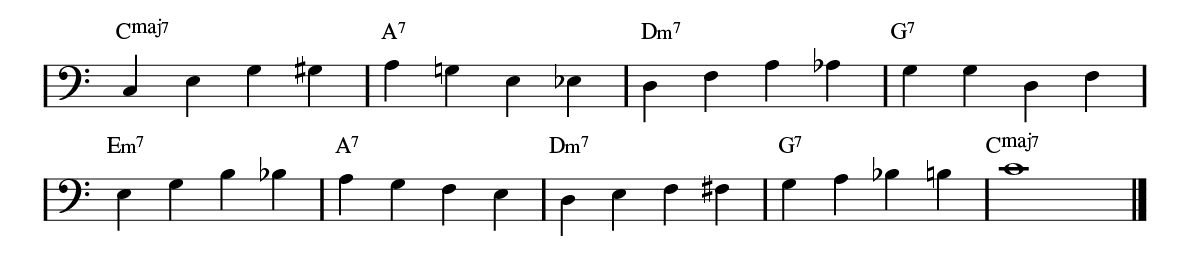

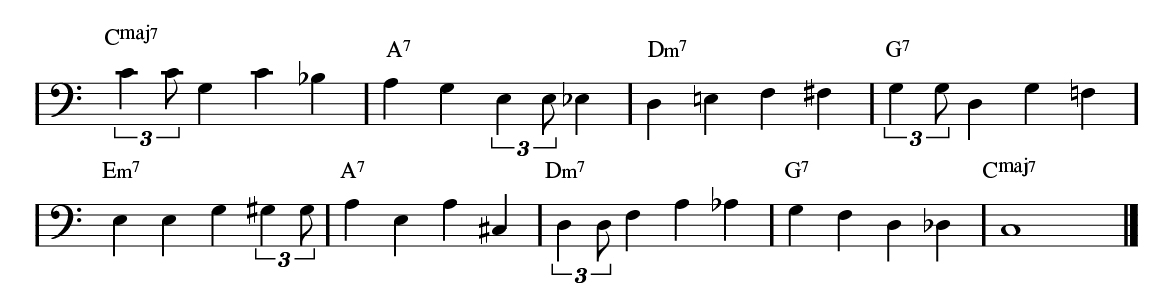

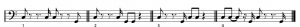

In addition to playing with strong fingertips, alignment between the hands can be improved with various practice strategies, such as:

- playing with differing articulation in each hand (legato versus staccato) as shown in this video

- playing with different dynamics in each hand (forte versus piano) as shown in this video

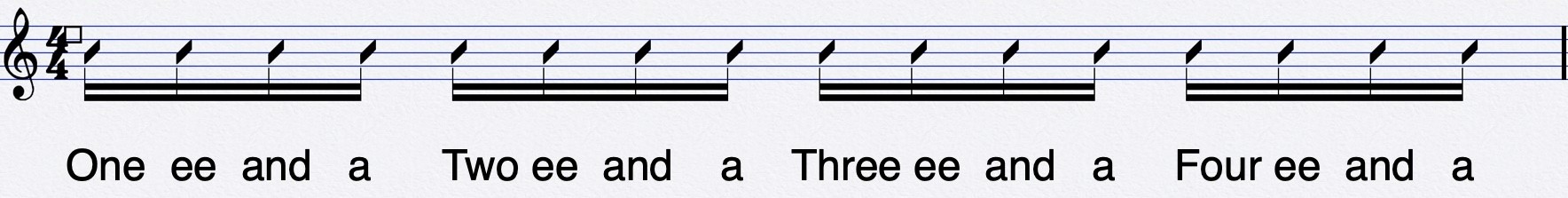

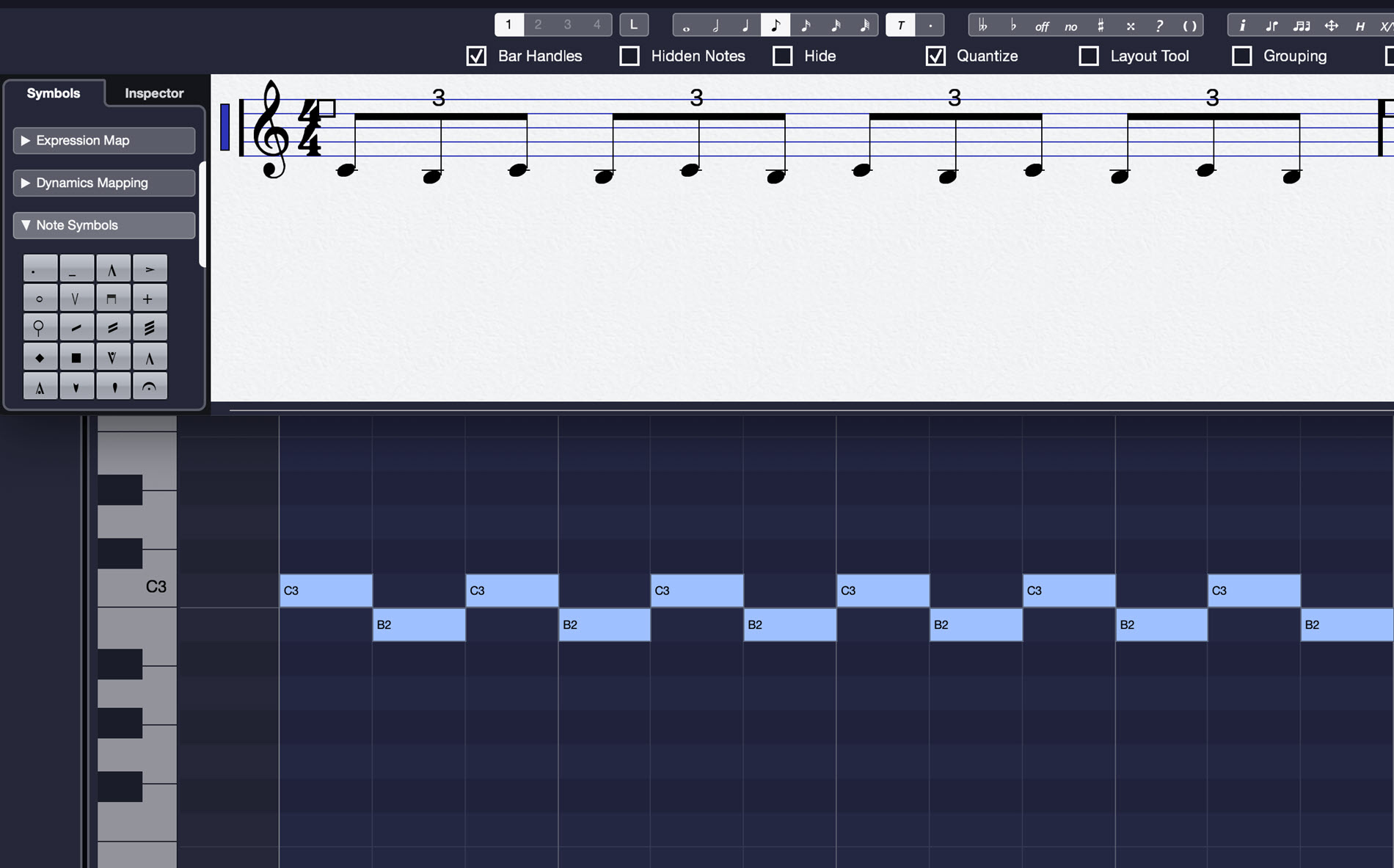

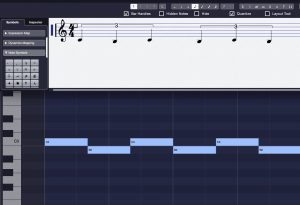

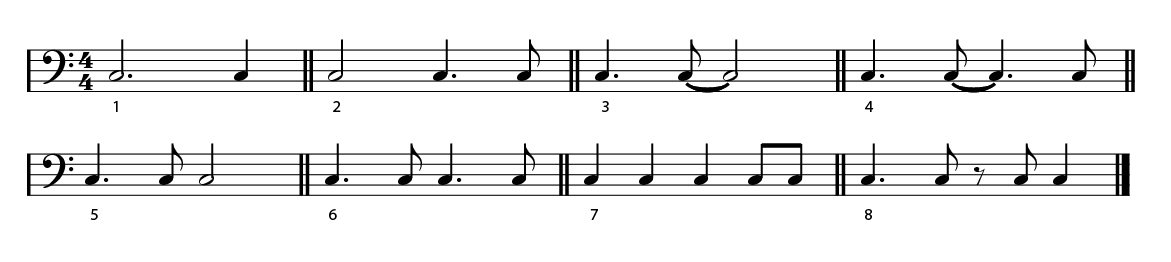

- playing in various rhythmic patterns and rhythmic groupings (both the same rhythm or differing rhythms in each hand) as shown in this video and in this video

- purposely playing the hands out-of-sync or in a staggered style (left before right or vice versa) as shown in this video

- various combinations of these strategies as shown in this video

The ear will then be able to hear each hand independently while the hands play together. Poorly aligned scales are often a result of both unhealthy physical habits and weak listening skills.

As for achieving a strong bridge in the piano playing hand, Carolyn Shaak helps her students visualize this position using the analogy of snowcapped mountain peaks (i.e., raised or pronounced metacarpophalangeal joints) versus a valley (collapsed metacarpophalangeal joints). In “The Shaak Technique Book,” which she wrote with her daughter Jamie, Carolyn uses several other effective analogies for improving hand shape, including: “Make a dog house, and make a muffin not a pancake.”

Another tip is to have students stretch out their fingers on a tabletop and then gently bring their fingers together to a point, thus raising the knuckles. Students then need to learn how to lift and drop the fingers from each metacarpophalangeal joint effectively.

Fix It: Ulna Deviation

Ulna deviation is all too common in piano playing. According to Medical News Today, it is defined as “a medical condition that causes the joints in the wrist and hand to shift so that the fingers bend toward the ulna bone on the outside of the forearm.”

Ulna deviation is all too common in piano playing. According to Medical News Today, it is defined as “a medical condition that causes the joints in the wrist and hand to shift so that the fingers bend toward the ulna bone on the outside of the forearm.”

Ulna deviation is particularly prevalent when students move to playing scales and arpeggios over several octaves and must reach the highest and lowest registers of the piano. Rather than playing with correct alignment of the arm behind the fingers, a twisted position develops such that the thumb dominates the hand position and is aligned with the arm.

When the pianist navigates the keyboard in this position, the fingers are left unsupported and unguided by the arm. As such, piano tone can be compromised, dexterity is lost and injury can happen.

SOLUTION: To help curb this harmful habit, make students aware of their ulna deviation and show them how to correctly align the arm behind the palm instead of aligning it with the thumb, so that the arm guides the fingers. It is also helpful to have students think about the position of their elbows in relation to each hand. Tell your students to keep each of their elbows farther away from the trunk of their body to help facilitate better coordination in scale, and even more so when playing arpeggios. It is sometimes helpful to have students imagine a bunch of flowers growing from their armpits and not squish them, or an armpit balloon and not pop it.

SOLUTION: To help curb this harmful habit, make students aware of their ulna deviation and show them how to correctly align the arm behind the palm instead of aligning it with the thumb, so that the arm guides the fingers. It is also helpful to have students think about the position of their elbows in relation to each hand. Tell your students to keep each of their elbows farther away from the trunk of their body to help facilitate better coordination in scale, and even more so when playing arpeggios. It is sometimes helpful to have students imagine a bunch of flowers growing from their armpits and not squish them, or an armpit balloon and not pop it.

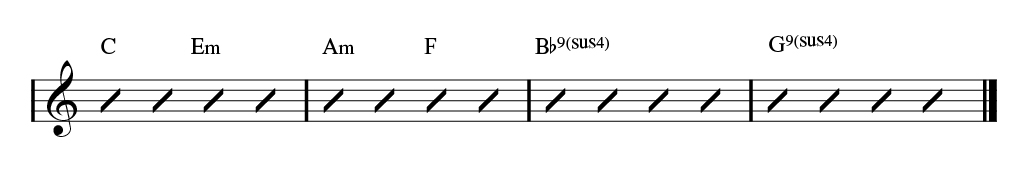

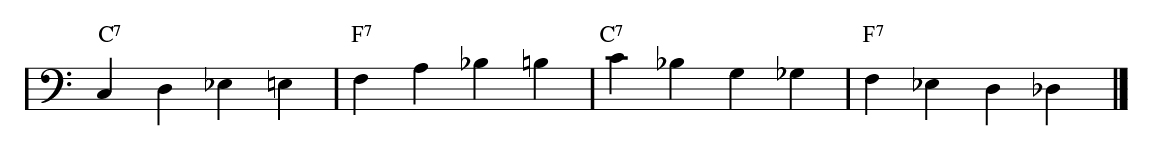

When I first teach scales, I begin with five-finger major pentascales; first played by each hand separately, then hands-together in contrary motion (as shown in this video). To help facilitate arm support behind each finger, I have students play with a semi-circular motion of the forearm from the elbow (counterclockwise, ascending in the right hand and vice versa in the left hand). Carolyn Shaak cleverly uses the image of a protractor to help her students achieve this motion and fluid five-finger playing.

I begin with contrary motion so that the movements of each hand and arm are a mirror image of one another, and the same fingers of each hand are aligned and played in sync. As such, the fingers are provided support, and the arm, hands and fingers learn to create fluid, rounded and beautifully shaped pentascales.

Developing a Well-Rounded Piano Technique

In short, scale and arpeggio practice are vital to building and maintaining a well-rounded piano technique. Knowledge of scale and chord patterns helps support elements of musicianship, such as ear training, critical listening, and theory and analyses. In addition, practicing scales and arpeggios can assist in improving keyboard skills like sight playing, score reading and keyboard harmony.

Developing a healthy physical approach to piano playing includes achieving a good hand shape and finger action in all scale and arpeggio playing. This will result in more even and musically played scales, injury prevention and, most importantly, lifelong music-making at the keyboard.

In 2007, I remember thinking, “Wow, this is so cool! I can get my email on my phone!” That was before I knew better.

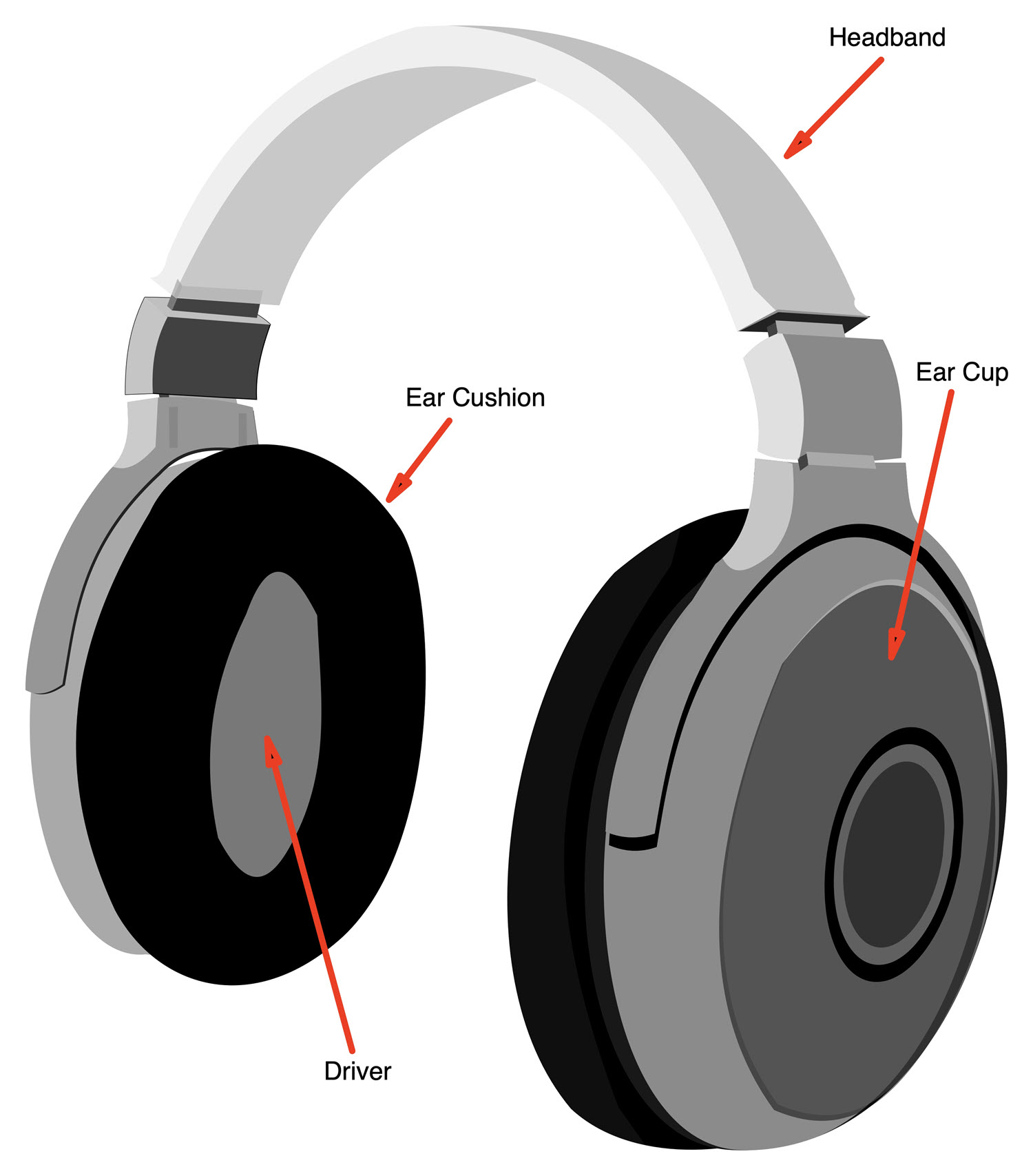

In 2007, I remember thinking, “Wow, this is so cool! I can get my email on my phone!” That was before I knew better. If I use my computer, I stay focused thanks to a few timers that block certain time-wasting websites. Furthermore, recognizing locations where you work best will help you avoid burgling time from yourself. When I have some extended writing or computer work to do, my go-to productive environment is a coffee shop where I sit with my laptop and headphones, listening to idle chatter and the ambient sounds of a café from a website called Coffitivity. (And yes, I see the redundancy of sitting in a coffee shop while listening to fake coffee shop sounds, but it keeps me from getting up and socializing with every table.)

If I use my computer, I stay focused thanks to a few timers that block certain time-wasting websites. Furthermore, recognizing locations where you work best will help you avoid burgling time from yourself. When I have some extended writing or computer work to do, my go-to productive environment is a coffee shop where I sit with my laptop and headphones, listening to idle chatter and the ambient sounds of a café from a website called Coffitivity. (And yes, I see the redundancy of sitting in a coffee shop while listening to fake coffee shop sounds, but it keeps me from getting up and socializing with every table.) Oh, the countless times I’ve had an excellent plan for my free period, only to be presented with a pile of plastic, rods, screws and unidentified objects. (It’s always bass clarinets, right?)

Oh, the countless times I’ve had an excellent plan for my free period, only to be presented with a pile of plastic, rods, screws and unidentified objects. (It’s always bass clarinets, right?)

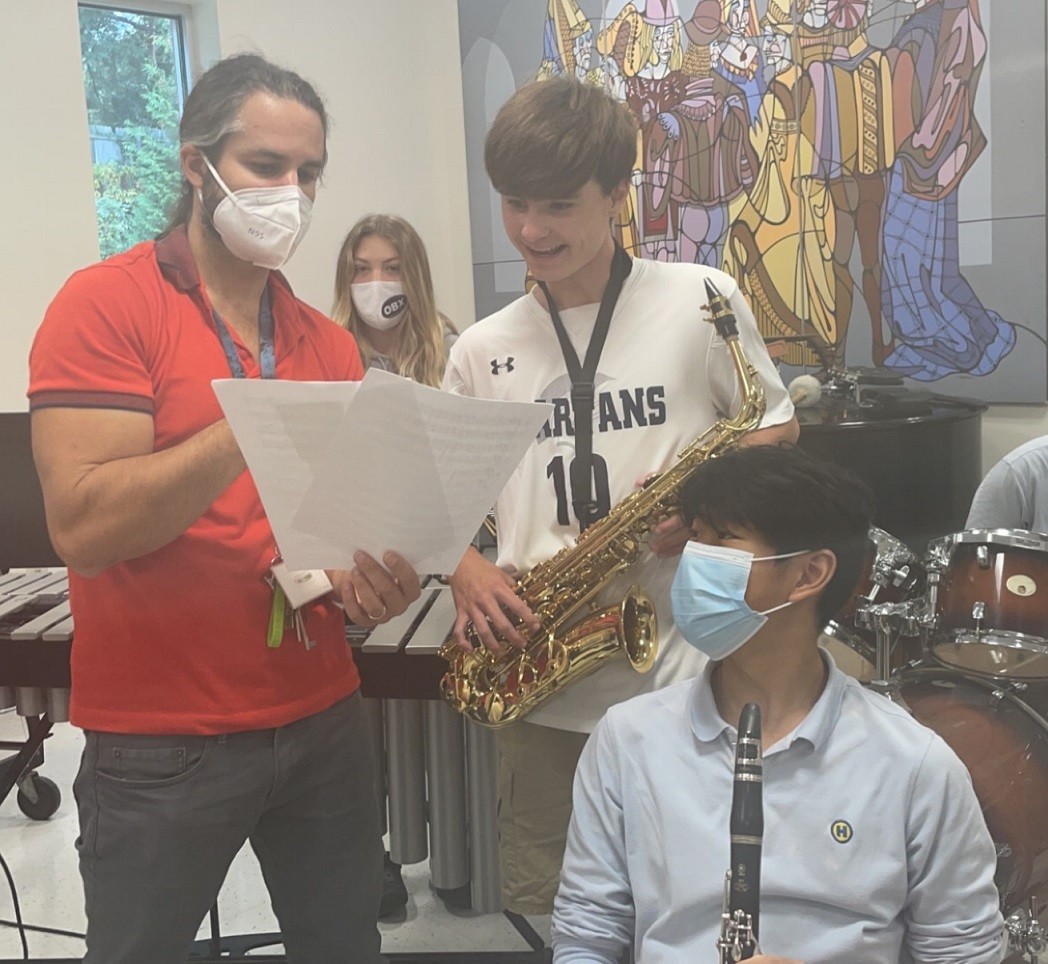

As a result, Gamon created an innovative role-playing game (RPG) that uses goals in the violin curriculum and overall grade units to unlock puzzles that advance the story. Called “Novice to Ninja” (read

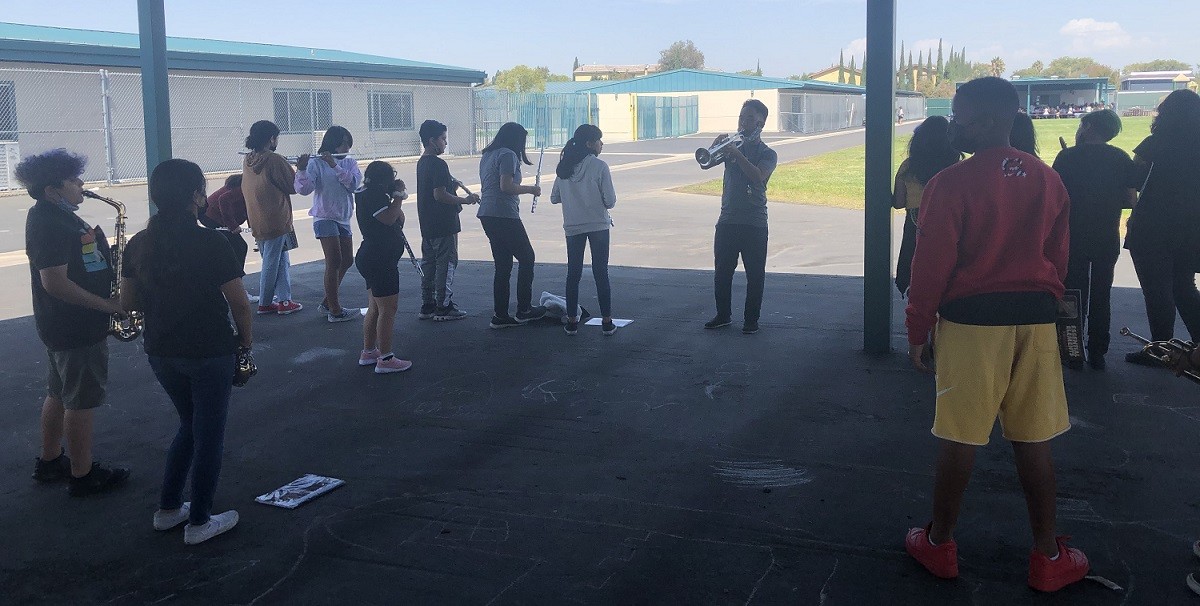

As a result, Gamon created an innovative role-playing game (RPG) that uses goals in the violin curriculum and overall grade units to unlock puzzles that advance the story. Called “Novice to Ninja” (read  Starting in 5th grade, Harrisburg students can choose a new instrument in strings, winds or brass. At the middle school, Gamon conducts the symphonic orchestra.

Starting in 5th grade, Harrisburg students can choose a new instrument in strings, winds or brass. At the middle school, Gamon conducts the symphonic orchestra. Furthermore, Gamon teaches Stagecraft and directs the school’s spring musical, which rehearses from September to March. In Stagecraft, students learn about lighting, sounds, props, costumes, construction building, design and marketing.

Furthermore, Gamon teaches Stagecraft and directs the school’s spring musical, which rehearses from September to March. In Stagecraft, students learn about lighting, sounds, props, costumes, construction building, design and marketing.

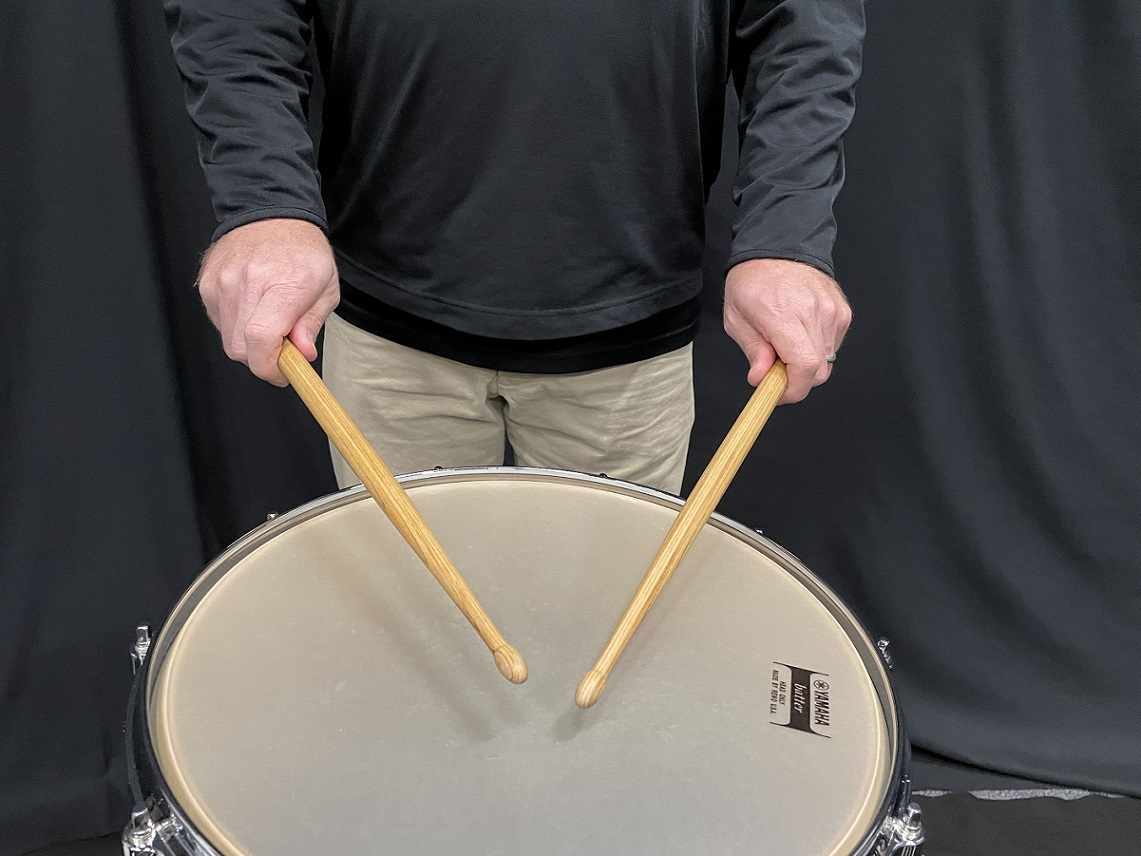

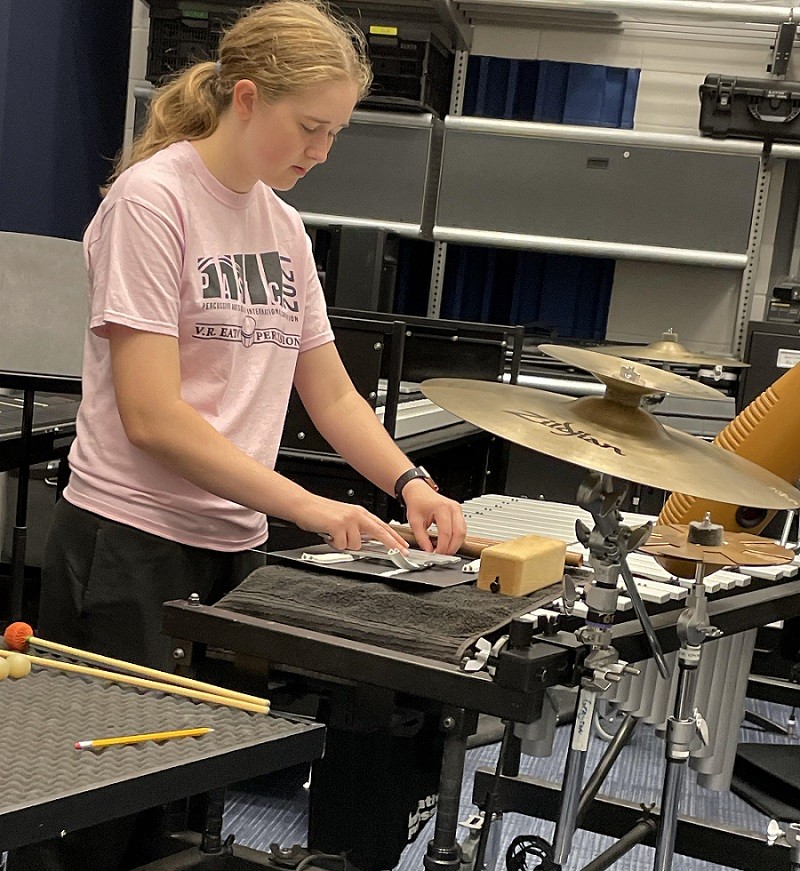

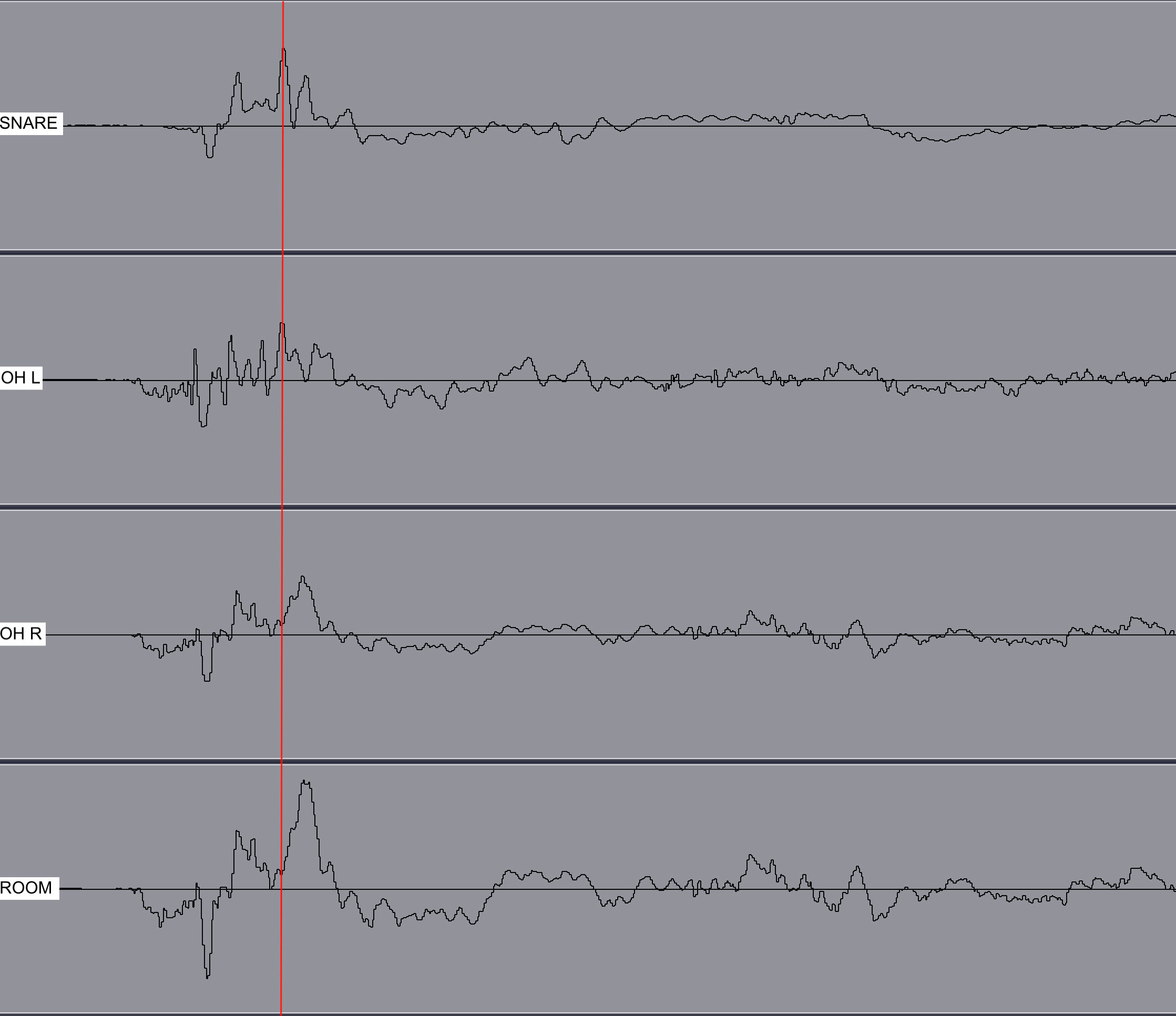

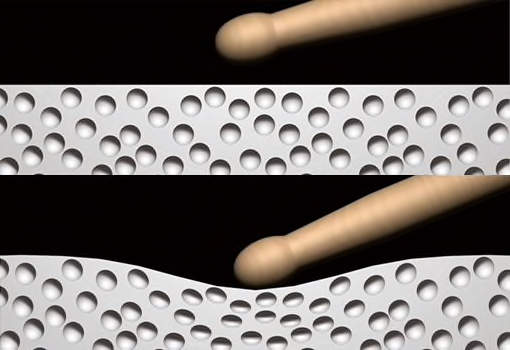

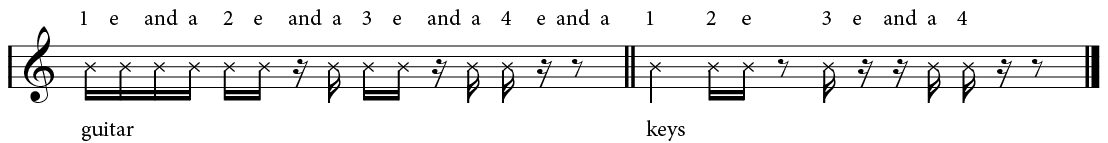

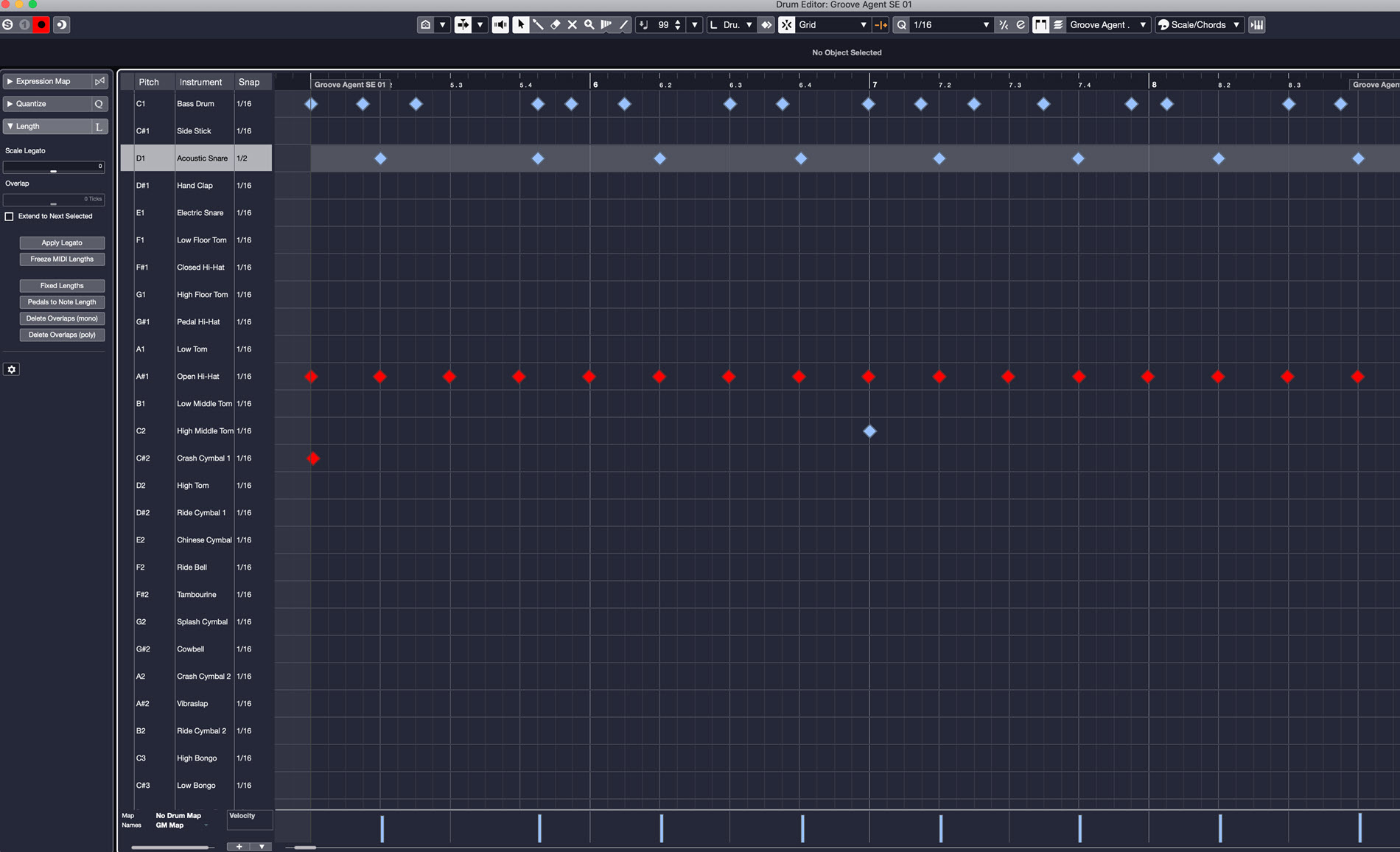

I have witnessed students just walk up to a snare drum and start playing. However, it is important to adjust the drum to the proper height so that the bead of the stick hits the drumhead at the optimal point. If the drum is not at the proper height, students will have tension in the shoulder.

I have witnessed students just walk up to a snare drum and start playing. However, it is important to adjust the drum to the proper height so that the bead of the stick hits the drumhead at the optimal point. If the drum is not at the proper height, students will have tension in the shoulder. Fix it: Drum Set Up (

Fix it: Drum Set Up ( Tell students to use their dominant hand and put the drumstick inside the first knuckle of their pointer finger. They should position the drumstick so that approximately two-thirds of the stick is coming out the front of their hand. Let the drumstick drop and count how many bounces are created. Tell students to reposition the drumstick and try a different fulcrum. Again, have them count the number of bounces. If there are less bounces, students should move the drumstick the opposite way and see how many bounces are achieved.

Tell students to use their dominant hand and put the drumstick inside the first knuckle of their pointer finger. They should position the drumstick so that approximately two-thirds of the stick is coming out the front of their hand. Let the drumstick drop and count how many bounces are created. Tell students to reposition the drumstick and try a different fulcrum. Again, have them count the number of bounces. If there are less bounces, students should move the drumstick the opposite way and see how many bounces are achieved.

There are two grips that can be used on snare drum: matched grip or traditional grip. Because matched grip is used on snare drum, marimba, xylophone, timpani, bells and most percussion instruments in a concert ensemble, I have found that it’s best to start a student on matched grip.

There are two grips that can be used on snare drum: matched grip or traditional grip. Because matched grip is used on snare drum, marimba, xylophone, timpani, bells and most percussion instruments in a concert ensemble, I have found that it’s best to start a student on matched grip.

Students often play with flat fingers — with their nails visible on the keys — so they can see that they are playing the desired keys. However, a curved hand position where the tips of the fingers are used allows for more dexterous scale playing because the fingers are able to move with greater ease and speed. The fingers simply cannot move as quickly in a flattened position. When playing with flat fingers, there is also more friction between the fingers and the keys, which makes it difficult to play scales fast. Think of flat-fingered scale playing as akin to sprinting flat footed.

Students often play with flat fingers — with their nails visible on the keys — so they can see that they are playing the desired keys. However, a curved hand position where the tips of the fingers are used allows for more dexterous scale playing because the fingers are able to move with greater ease and speed. The fingers simply cannot move as quickly in a flattened position. When playing with flat fingers, there is also more friction between the fingers and the keys, which makes it difficult to play scales fast. Think of flat-fingered scale playing as akin to sprinting flat footed. On the other end of the spectrum, students may overdo curved hand positions and end up curling their fingers. As such, they grip the keys and play with what some teachers call “the claw.” Playing scales in this way necessitates a lot of physical effort as one muscle or set of muscles is needed to keep the fingers in this curled position, while another muscle or set is needed to lift and move the fingers.

On the other end of the spectrum, students may overdo curved hand positions and end up curling their fingers. As such, they grip the keys and play with what some teachers call “the claw.” Playing scales in this way necessitates a lot of physical effort as one muscle or set of muscles is needed to keep the fingers in this curled position, while another muscle or set is needed to lift and move the fingers. SOLUTION: The solution to correcting flat or curled fingers is similar. First, help your students understand that neither flat nor curled fingers are the most comfortable or ideal finger position for fast scale playing. In a neutral position, the fingers of the hand curve naturally, and this position is best for achieving superior scale and arpeggio playing. Here’s a simple exercise to help students find the natural curve of the fingers: Have them lift their arms to shoulder height at their sides and then drop their arms freely. Looking down, they will notice that their fingers are now in a naturally curved position.

SOLUTION: The solution to correcting flat or curled fingers is similar. First, help your students understand that neither flat nor curled fingers are the most comfortable or ideal finger position for fast scale playing. In a neutral position, the fingers of the hand curve naturally, and this position is best for achieving superior scale and arpeggio playing. Here’s a simple exercise to help students find the natural curve of the fingers: Have them lift their arms to shoulder height at their sides and then drop their arms freely. Looking down, they will notice that their fingers are now in a naturally curved position. Many students misunderstand the correct position of the thumb on the keys and try to play using too much of the thumb, or even attempt to play on the very tip of the distal phalanx rather than on the corner of it (the spot on each thumb where the nail meets flesh). As such, students sometimes incorrectly play with a straight rather than a slightly bent thumb.

Many students misunderstand the correct position of the thumb on the keys and try to play using too much of the thumb, or even attempt to play on the very tip of the distal phalanx rather than on the corner of it (the spot on each thumb where the nail meets flesh). As such, students sometimes incorrectly play with a straight rather than a slightly bent thumb. In addition, when passing the thumb in ascending right-hand and descending left-hand scales or arpeggios, many students begin moving the thumb under the hand too late, or keep the thumb straight rather than slightly bent at the proximal interphalangeal joint when moving it.

In addition, when passing the thumb in ascending right-hand and descending left-hand scales or arpeggios, many students begin moving the thumb under the hand too late, or keep the thumb straight rather than slightly bent at the proximal interphalangeal joint when moving it. SOLUTION: The best way to help a student understand where to play on the thumb is to simply point it out to them — touch the part of thumb that should make contact with the key. If a student has been playing with the wrong part of their thumb, or without bending it from the proximal interphalangeal joint, or at the wrong angle in relation to the key, the correct procedure will feel strange and unfamiliar to them. It will take time for them to change their habit and learn to use the thumb properly and effectively.

SOLUTION: The best way to help a student understand where to play on the thumb is to simply point it out to them — touch the part of thumb that should make contact with the key. If a student has been playing with the wrong part of their thumb, or without bending it from the proximal interphalangeal joint, or at the wrong angle in relation to the key, the correct procedure will feel strange and unfamiliar to them. It will take time for them to change their habit and learn to use the thumb properly and effectively. To facilitate improved thumb motion under the hand in scale and arpeggio playing, break down this small, but surprisingly challenging, movement into several steps. I recommend working on this motion first in scale playing versus arpeggios and start with a scale with many black keys. According to the book, “Chopin: Pianist and Teacher as Seen by His Pupils,” Chopin advocated for having students start with B major (right hand) and then D flat major (left hand) scales with the position of the thumb in mind. These are also some of the easiest scales to coordinate in hands-together playing as the thumbs of each hand come together on the white keys. Together with G flat major, these are the first octave scales I teach a student to play hands together. These scales are also excellent for achieving good passing of the thumbs as fingers 2, 3 and 4 play black keys, which are raised, allowing for a natural space to emerge on the keyboard in which the thumb can move freely and easily.

To facilitate improved thumb motion under the hand in scale and arpeggio playing, break down this small, but surprisingly challenging, movement into several steps. I recommend working on this motion first in scale playing versus arpeggios and start with a scale with many black keys. According to the book, “Chopin: Pianist and Teacher as Seen by His Pupils,” Chopin advocated for having students start with B major (right hand) and then D flat major (left hand) scales with the position of the thumb in mind. These are also some of the easiest scales to coordinate in hands-together playing as the thumbs of each hand come together on the white keys. Together with G flat major, these are the first octave scales I teach a student to play hands together. These scales are also excellent for achieving good passing of the thumbs as fingers 2, 3 and 4 play black keys, which are raised, allowing for a natural space to emerge on the keyboard in which the thumb can move freely and easily. Some students try to play scales with a hand(s) that is not kept in line with the arm at the wrist, such that the position of the wrist joint is overly high or overly low.

Some students try to play scales with a hand(s) that is not kept in line with the arm at the wrist, such that the position of the wrist joint is overly high or overly low. As such, ease of movement is lost, tension can develop and injury can ensue when utilizing awkward wrist positions while playing.

As such, ease of movement is lost, tension can develop and injury can ensue when utilizing awkward wrist positions while playing. Some teachers prefer to use the image of a “floating wrist” to help students achieve an improved mid-range position. When I inherit a student who has been taught to make a dropping motion of the wrist on every finger action to achieve a weighty sounding scale, I encourage them to strive for “beautifully gliding” scales. As such, the arm guides the fingers so that the hands and arms move laterally (or horizontally) over the keys like a figure skater glides effortlessly over a glassy lake, rather than creating the visual and sonic effect of choppy waves. Gliding scales can be further enhanced with a gradual and even crescendo ascending and diminuendo descending. In this way, they are rhythmically even and musically shaped.

Some teachers prefer to use the image of a “floating wrist” to help students achieve an improved mid-range position. When I inherit a student who has been taught to make a dropping motion of the wrist on every finger action to achieve a weighty sounding scale, I encourage them to strive for “beautifully gliding” scales. As such, the arm guides the fingers so that the hands and arms move laterally (or horizontally) over the keys like a figure skater glides effortlessly over a glassy lake, rather than creating the visual and sonic effect of choppy waves. Gliding scales can be further enhanced with a gradual and even crescendo ascending and diminuendo descending. In this way, they are rhythmically even and musically shaped. Some students are able to implement the natural curve of the hand in their scale playing, but then they allow the final knuckle or distal interphalangeal joint of fingers 1, 2, 3 and/or 4 to collapse as one or more fingers depress the keys (this happens most often with finger 4, in my experience). According to Carolyn and Jamie Shaak in “

Some students are able to implement the natural curve of the hand in their scale playing, but then they allow the final knuckle or distal interphalangeal joint of fingers 1, 2, 3 and/or 4 to collapse as one or more fingers depress the keys (this happens most often with finger 4, in my experience). According to Carolyn and Jamie Shaak in “ Collapsing joints can result in two-handed scale playing in which the hands are unaligned or unsynchronized because the final finger joint in one or both hands is not firm and, therefore, not moving with control, resulting in differing speeds in the dissent of the keys played by each hand.

Collapsing joints can result in two-handed scale playing in which the hands are unaligned or unsynchronized because the final finger joint in one or both hands is not firm and, therefore, not moving with control, resulting in differing speeds in the dissent of the keys played by each hand. SOLUTION: Collapsing knuckle joints are a bad habit and teachers must be vigilant and tireless in their efforts to correct this bad habit among their students. First, students must be aware of how it feels to use the fingertips correctly versus incorrectly.

SOLUTION: Collapsing knuckle joints are a bad habit and teachers must be vigilant and tireless in their efforts to correct this bad habit among their students. First, students must be aware of how it feels to use the fingertips correctly versus incorrectly. Ulna deviation is all too common in piano playing. According to

Ulna deviation is all too common in piano playing. According to  SOLUTION: To help curb this harmful habit, make students aware of their ulna deviation and show them how to correctly align the arm behind the palm instead of aligning it with the thumb, so that the arm guides the fingers. It is also helpful to have students think about the position of their elbows in relation to each hand. Tell your students to keep each of their elbows farther away from the trunk of their body to help facilitate better coordination in scale, and even more so when playing arpeggios. It is sometimes helpful to have students imagine a bunch of flowers growing from their armpits and not squish them, or an armpit balloon and not pop it.

SOLUTION: To help curb this harmful habit, make students aware of their ulna deviation and show them how to correctly align the arm behind the palm instead of aligning it with the thumb, so that the arm guides the fingers. It is also helpful to have students think about the position of their elbows in relation to each hand. Tell your students to keep each of their elbows farther away from the trunk of their body to help facilitate better coordination in scale, and even more so when playing arpeggios. It is sometimes helpful to have students imagine a bunch of flowers growing from their armpits and not squish them, or an armpit balloon and not pop it.

One of the most common pedaling problems I see is when students lift their entire foot and leg to change the pedal. (I informally call this “horse pedal” because it reminds me of a horse pawing the ground.) This motion not only takes away all control of pedal depth and timing, but it also causes an interruption in the phrase. Horse pedal usually occurs when a student is not aware of the musical and physical implications of pedaling incorrectly. Luckily, it can be fixed with a bit of focus and attention to the problem.

One of the most common pedaling problems I see is when students lift their entire foot and leg to change the pedal. (I informally call this “horse pedal” because it reminds me of a horse pawing the ground.) This motion not only takes away all control of pedal depth and timing, but it also causes an interruption in the phrase. Horse pedal usually occurs when a student is not aware of the musical and physical implications of pedaling incorrectly. Luckily, it can be fixed with a bit of focus and attention to the problem. In order to use and change the pedal efficiently and effectively, your student’s heel should remain on the ground, and the pedal should be played with the ball of the foot, right below the first and second toes. If a student is too short to reach the pedal comfortably, use a pedal extender (see picture to the left), which can be purchased for a relatively low cost.

In order to use and change the pedal efficiently and effectively, your student’s heel should remain on the ground, and the pedal should be played with the ball of the foot, right below the first and second toes. If a student is too short to reach the pedal comfortably, use a pedal extender (see picture to the left), which can be purchased for a relatively low cost. It is very common for pianists to jam down the pedal when they feel nervous or uncomfortable with a passage. (Raise your hand if you’ve ever done that!) When teachers and students are nervous or not as well prepared as they would like, their focus becomes much more limited.

It is very common for pianists to jam down the pedal when they feel nervous or uncomfortable with a passage. (Raise your hand if you’ve ever done that!) When teachers and students are nervous or not as well prepared as they would like, their focus becomes much more limited.

Communication

Communication Say “a child with autism” rather than “an autistic child.” This might seem like a small and unimportant distinction, but to the child and his or her parents, this is a big deal.

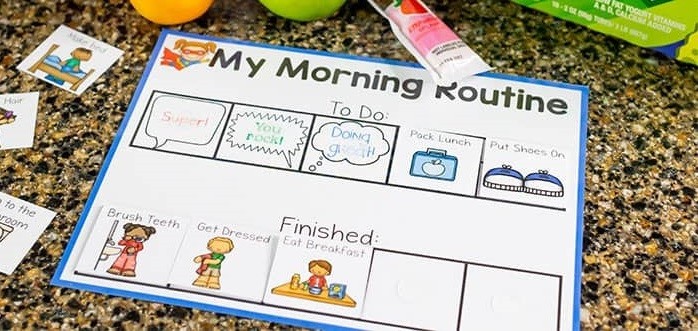

Say “a child with autism” rather than “an autistic child.” This might seem like a small and unimportant distinction, but to the child and his or her parents, this is a big deal. Some children with autism are used to using picture schedules (see photo to the right) at home or school, and I often incorporate that into lessons. (You can easily make one with Velcro and poster board.) Others like to begin and end with the same song but are able to have more flexibility during the lesson. An example of a sample lesson would include: 5-Finger Patterns, Improvisation, Repertoire Piece, Notes Names, Student’s Choice, “Hokey-Pokey.”

Some children with autism are used to using picture schedules (see photo to the right) at home or school, and I often incorporate that into lessons. (You can easily make one with Velcro and poster board.) Others like to begin and end with the same song but are able to have more flexibility during the lesson. An example of a sample lesson would include: 5-Finger Patterns, Improvisation, Repertoire Piece, Notes Names, Student’s Choice, “Hokey-Pokey.”

Moore feels passionate about percussion ensemble as a relatively new genre. “We’re in the golden age of concert percussion composition right now,” Moore says. “A lot of the best music written for the art form is coming out every year.”

Moore feels passionate about percussion ensemble as a relatively new genre. “We’re in the golden age of concert percussion composition right now,” Moore says. “A lot of the best music written for the art form is coming out every year.” Moore grew Eaton’s percussion ensemble, which meets between the end of November to mid-March, partly from the organic expansion of the school. As the third high school in the

Moore grew Eaton’s percussion ensemble, which meets between the end of November to mid-March, partly from the organic expansion of the school. As the third high school in the  In 2020, Eaton won the North Texas Percussion Festival for high school large group on the weekend that started spring break in early March. “This festival was the very last in-person thing that anybody did [before COVID shutdowns],” Moore says.

In 2020, Eaton won the North Texas Percussion Festival for high school large group on the weekend that started spring break in early March. “This festival was the very last in-person thing that anybody did [before COVID shutdowns],” Moore says. As a composer himself, Moore had written a marimba choir piece, titled “Together,” to help musicians get through the early days of the pandemic. Moore had posted the composition on social media and requested video submissions. With 111 submissions from middle school to adult performers, including some Eaton High School students, the song was produced into a compiled video by Cameron Sather and aired on

As a composer himself, Moore had written a marimba choir piece, titled “Together,” to help musicians get through the early days of the pandemic. Moore had posted the composition on social media and requested video submissions. With 111 submissions from middle school to adult performers, including some Eaton High School students, the song was produced into a compiled video by Cameron Sather and aired on  By April 2021, Moore accepted the invitation to perform at PASIC in November. Since groups typically don’t find out about PASIC performances until the summertime, he now felt ahead of the game. But Moore made a pact with himself and the other directors to maintain a work/life balance while preparing for the high-profile show in the percussion ensemble’s off-season.

By April 2021, Moore accepted the invitation to perform at PASIC in November. Since groups typically don’t find out about PASIC performances until the summertime, he now felt ahead of the game. But Moore made a pact with himself and the other directors to maintain a work/life balance while preparing for the high-profile show in the percussion ensemble’s off-season. Moore and Vogt have crafted a 45-minute PASIC 2021 concert that he describes as “collaborative, flowing and fresh.” With a mix of smaller groupings to larger percussion orchestra, the program brings together all of Eaton’s 33 percussion ensemble members plus seven string players and five dance (color guard) students performing seven songs, each with a distinct sound and purpose.

Moore and Vogt have crafted a 45-minute PASIC 2021 concert that he describes as “collaborative, flowing and fresh.” With a mix of smaller groupings to larger percussion orchestra, the program brings together all of Eaton’s 33 percussion ensemble members plus seven string players and five dance (color guard) students performing seven songs, each with a distinct sound and purpose.

V.R. Eaton’s 45-minute performance at the November 2021 Percussive Arts Society International Convention will comprise the following mix of pieces.

V.R. Eaton’s 45-minute performance at the November 2021 Percussive Arts Society International Convention will comprise the following mix of pieces.

First, purchase a set of 25 to 30 mini play doughs. Next, borrow a set of vinyl spot markers from the gym. Make sure you have one per student. Space out the spot markers across the classroom before your students arrive.

First, purchase a set of 25 to 30 mini play doughs. Next, borrow a set of vinyl spot markers from the gym. Make sure you have one per student. Space out the spot markers across the classroom before your students arrive. Clapping games are another way to give your students a fun break but still practice music. Try clapping games as a stationary break, especially when your classroom is too excitable to do line dances.

Clapping games are another way to give your students a fun break but still practice music. Try clapping games as a stationary break, especially when your classroom is too excitable to do line dances. Use Orff stories to incorporate both reading and creativity. These stories are perfect for events like reading week, when your school may ask you to read instead of play instruments: Why not do both?

Use Orff stories to incorporate both reading and creativity. These stories are perfect for events like reading week, when your school may ask you to read instead of play instruments: Why not do both?

Tool 2: Nibble on Some Chocolate

Tool 2: Nibble on Some Chocolate Tool 4: Use Choice Architecture

Tool 4: Use Choice Architecture

Accents and Accessories

Accents and Accessories DO have your students purchase their own shoes

DO have your students purchase their own shoes

Concert Ticket Sales

Concert Ticket Sales Ensemble and Instrument Fees

Ensemble and Instrument Fees Large food chains and local restaurants are happy to profit share in exchange for increased drive-thru business and in-restaurant patrons on less busy nights. Restaurants, such as

Large food chains and local restaurants are happy to profit share in exchange for increased drive-thru business and in-restaurant patrons on less busy nights. Restaurants, such as  The “Everything” Deal

The “Everything” Deal

Before we start talking about social marketing, you must understand the difference between branding and personal branding. Branding is the process for creating a name, logo or symbol that identifies and differentiates your product and services from your competitor’s (

Before we start talking about social marketing, you must understand the difference between branding and personal branding. Branding is the process for creating a name, logo or symbol that identifies and differentiates your product and services from your competitor’s ( Ready to build your online presence? You want to control your message and how people perceive you on the internet. So, build a personal website and set up your email address and social media accounts.

Ready to build your online presence? You want to control your message and how people perceive you on the internet. So, build a personal website and set up your email address and social media accounts. If you want to start a private lesson studio, find a location and set up the room where you can teach. But how do you find students? I recommend volunteering at your local public school’s music program. Ask the director if you can teach a masterclass in exchange for passing out your business card (aka, your information). As you build your reputation, parents will hire you to teach private lessons to their children.

If you want to start a private lesson studio, find a location and set up the room where you can teach. But how do you find students? I recommend volunteering at your local public school’s music program. Ask the director if you can teach a masterclass in exchange for passing out your business card (aka, your information). As you build your reputation, parents will hire you to teach private lessons to their children. How Do I Start?

How Do I Start?

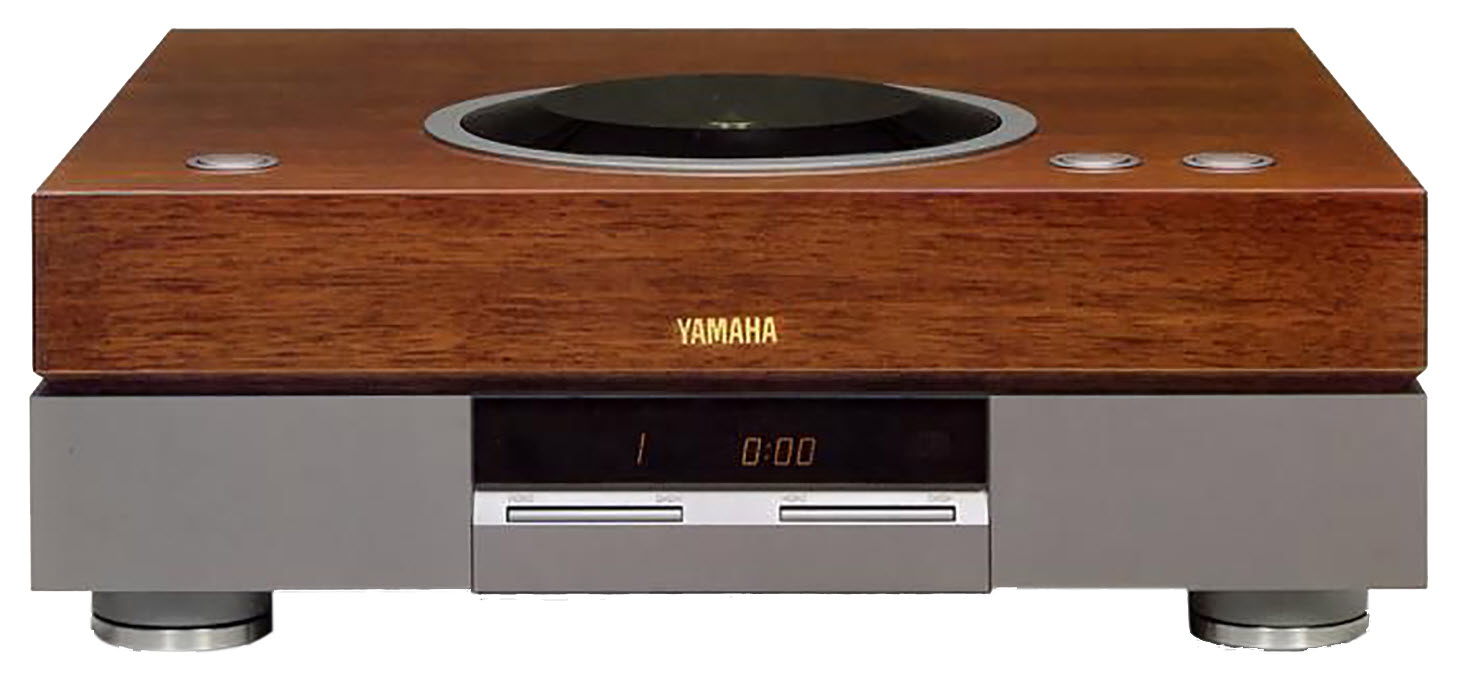

The North Carolina Music Education Association conference gives us an opportunity to connect with all of you and to remind you that Yamaha is your partner in music education, not just through our great instruments and professional audio products but also with resources, support and professional development. We know how difficult this past year has been as we have navigated through these uncertain times, and we want to express our appreciation and gratitude for everyone involved in making this conference possible. We want to continue to hear about your programs and learn about you and your specific needs to see how Yamaha can partner with you to help.

The North Carolina Music Education Association conference gives us an opportunity to connect with all of you and to remind you that Yamaha is your partner in music education, not just through our great instruments and professional audio products but also with resources, support and professional development. We know how difficult this past year has been as we have navigated through these uncertain times, and we want to express our appreciation and gratitude for everyone involved in making this conference possible. We want to continue to hear about your programs and learn about you and your specific needs to see how Yamaha can partner with you to help.

To help the board understand the value of the capital expense, Gibb-Clark has invited its members to performances and provided updates on participation, competition results and equipment use. In fact, all the audiovisual equipment bought by the show choir has been used for the other choirs and musicals while the sound system has also been utilized at graduation. “It was an investment beyond the show choir,” Gibb-Clark says.

To help the board understand the value of the capital expense, Gibb-Clark has invited its members to performances and provided updates on participation, competition results and equipment use. In fact, all the audiovisual equipment bought by the show choir has been used for the other choirs and musicals while the sound system has also been utilized at graduation. “It was an investment beyond the show choir,” Gibb-Clark says. At Highland, each ensemble focuses on different musical genres and gives students different learning and performance opportunities. For example, the madrigals sing at the

At Highland, each ensemble focuses on different musical genres and gives students different learning and performance opportunities. For example, the madrigals sing at the

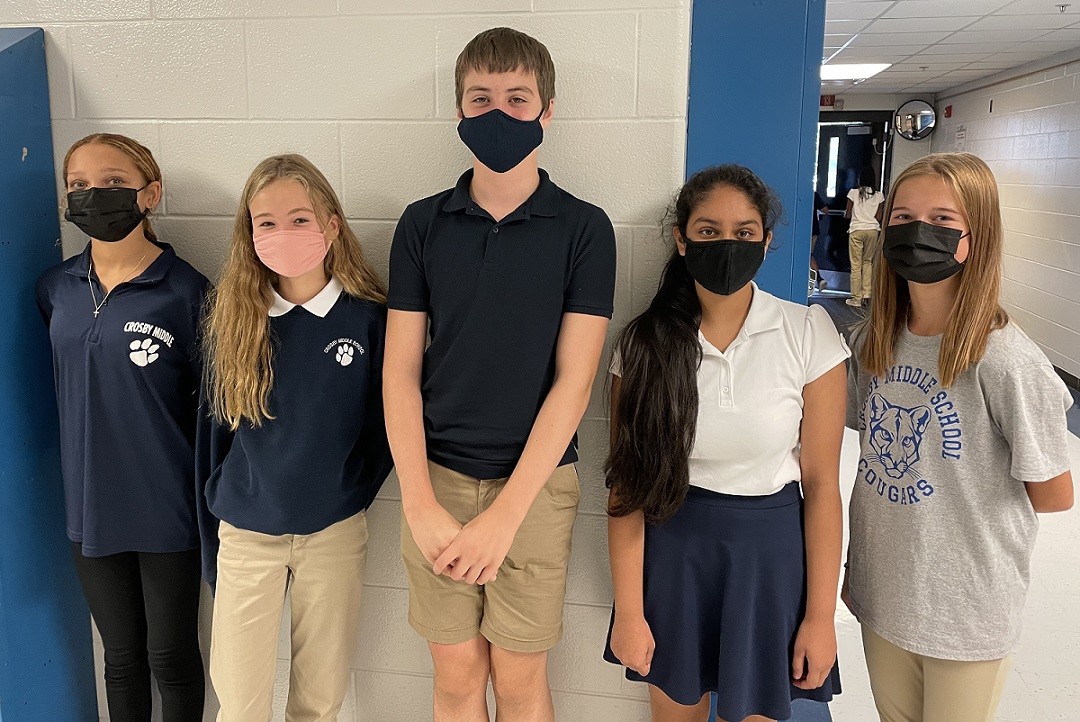

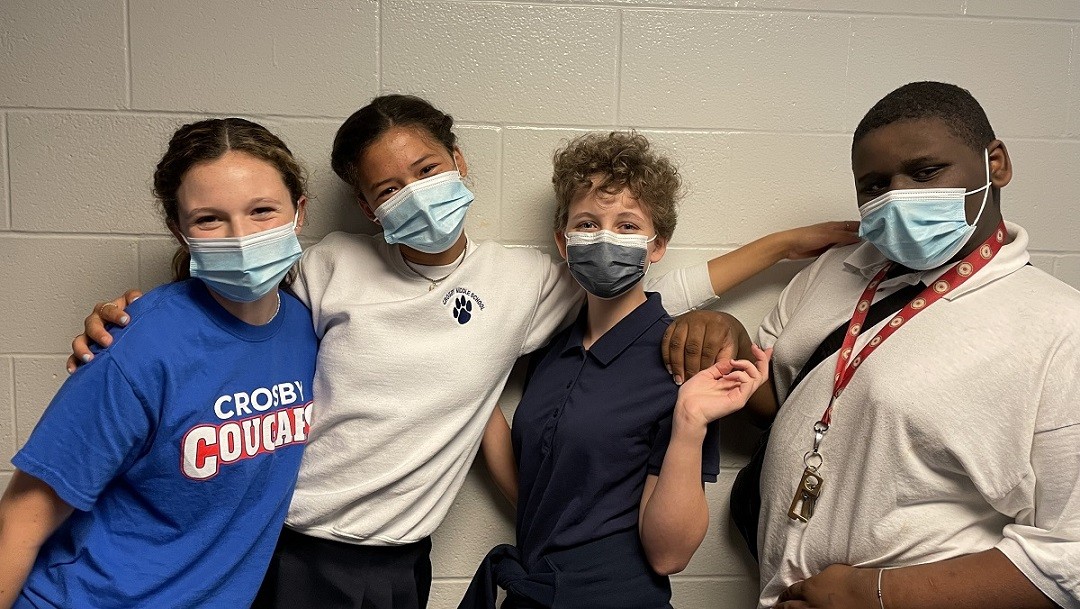

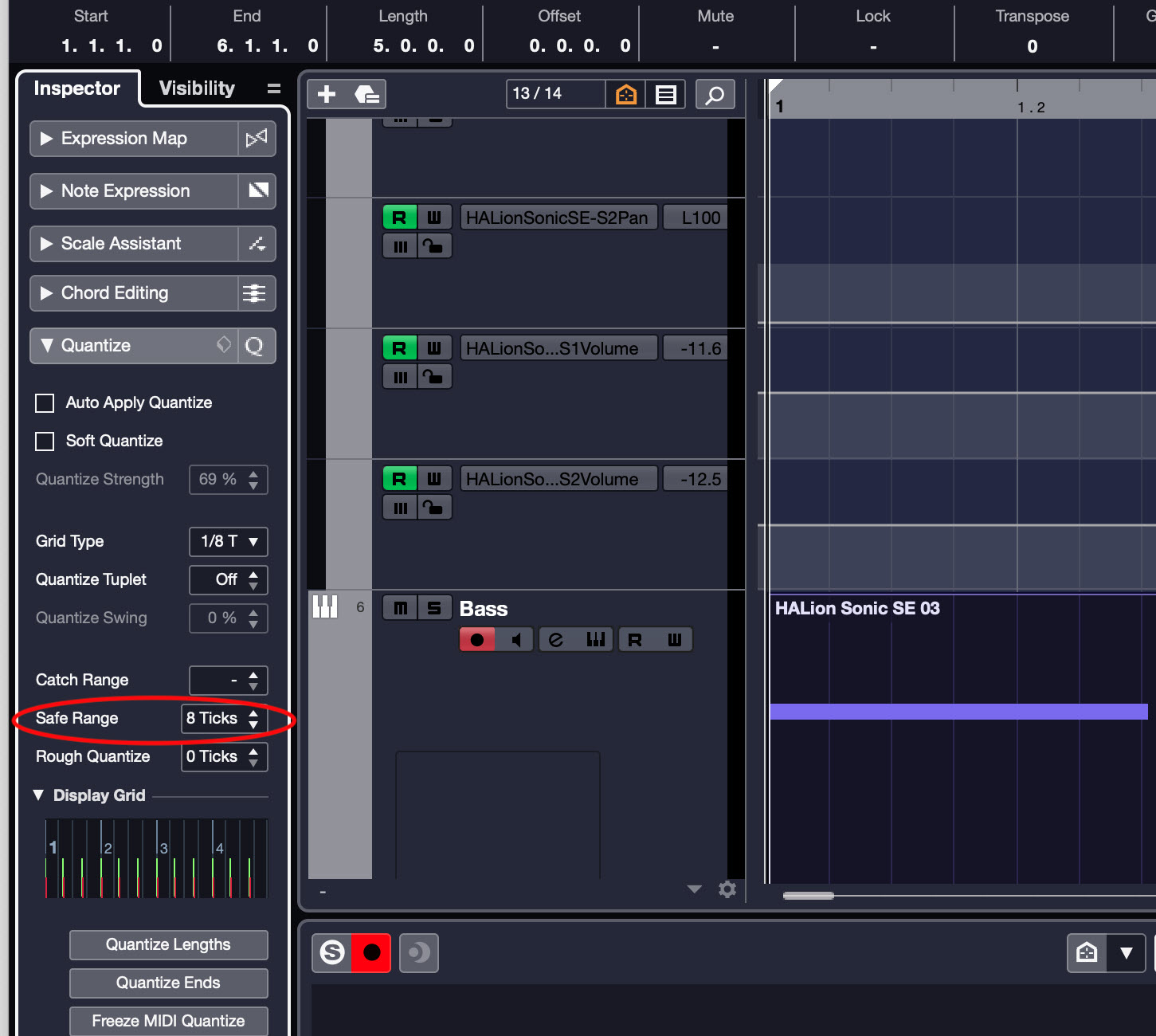

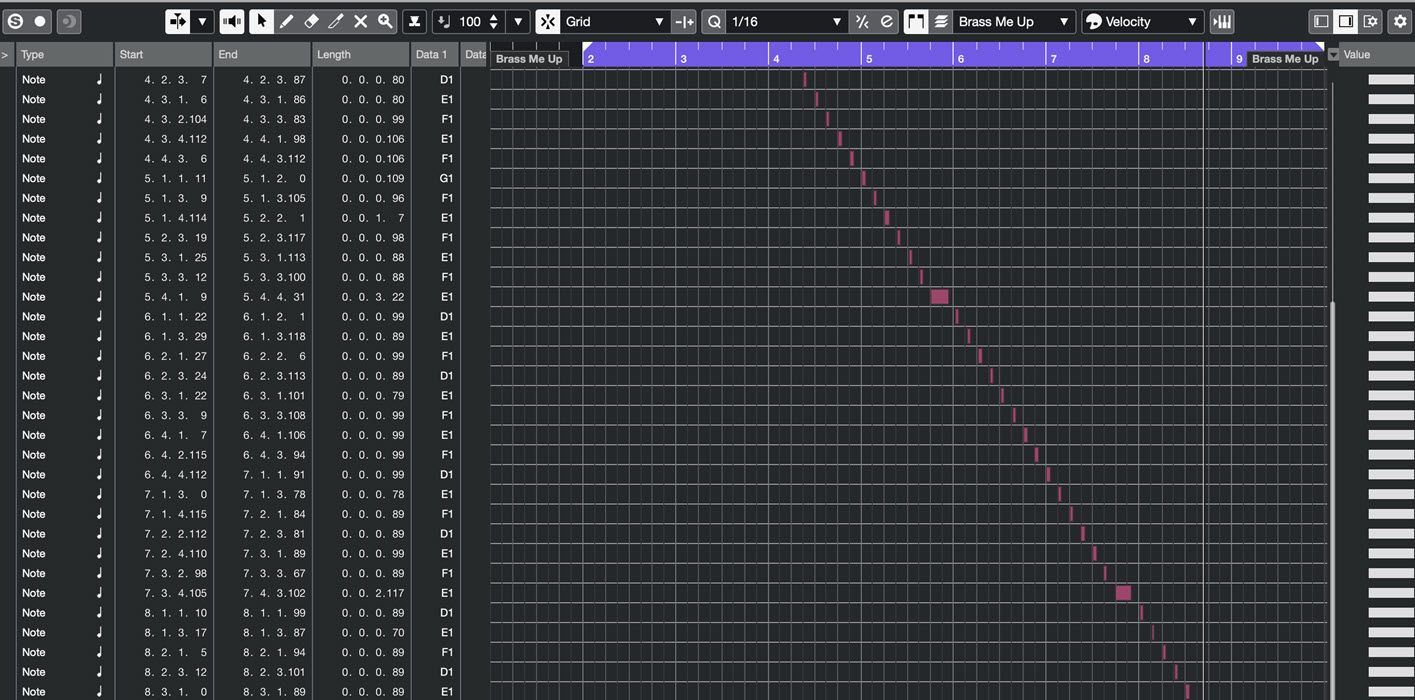

Cox has a dual role at Crosby, directing 6th, 7th and 8th grade choirs as well as teaching digital music classes that are part of the school’s overall STEAM (science, technology, engineering, the arts and mathematics) program.

Cox has a dual role at Crosby, directing 6th, 7th and 8th grade choirs as well as teaching digital music classes that are part of the school’s overall STEAM (science, technology, engineering, the arts and mathematics) program. She’ll also use visual cues, perhaps requesting that students touch their noses when they can identify the first dynamic change or use

She’ll also use visual cues, perhaps requesting that students touch their noses when they can identify the first dynamic change or use  They also participate in three to six formal evening concerts for family, some in collaboration with the high school choir from nearby

They also participate in three to six formal evening concerts for family, some in collaboration with the high school choir from nearby  Beyond just teaching the mechanics of singing, Cox strives to create a community where everyone values each other’s contributions. Each choir class elects several officers who help with taking attendance and mentoring new students. “Sometimes my strongest leaders are not necessarily the strongest musicians,” she says. “I’m looking not just for musical leaders but [also for] leaders in how to rehearse or … students who are really encouraging of their peers. … I try to find and identify one area in which they’re really strong and try to foster that area.”

Beyond just teaching the mechanics of singing, Cox strives to create a community where everyone values each other’s contributions. Each choir class elects several officers who help with taking attendance and mentoring new students. “Sometimes my strongest leaders are not necessarily the strongest musicians,” she says. “I’m looking not just for musical leaders but [also for] leaders in how to rehearse or … students who are really encouraging of their peers. … I try to find and identify one area in which they’re really strong and try to foster that area.” In Cox’s digital music courses, students come from all parts of the school. Some have performing arts classes while others don’t. “It’s nice that they can get a different approach to the arts,” she says.

In Cox’s digital music courses, students come from all parts of the school. Some have performing arts classes while others don’t. “It’s nice that they can get a different approach to the arts,” she says.

Joining a 22-year leader — Kevin Bennett — at the helm, Bock did not want to rock the boat. “Any time you go into a program as a second director, you don’t get a clean slate to just change it to whatever you want,” Bock says. “Kevin definitely established an amazing culture. But you always want to make the program feel a little bit more like your own. … It was really important for me to identify what my vision was — what do I bring to the table in this already established, successful program?”

Joining a 22-year leader — Kevin Bennett — at the helm, Bock did not want to rock the boat. “Any time you go into a program as a second director, you don’t get a clean slate to just change it to whatever you want,” Bock says. “Kevin definitely established an amazing culture. But you always want to make the program feel a little bit more like your own. … It was really important for me to identify what my vision was — what do I bring to the table in this already established, successful program?” “It was at the top of every single paper, but when I asked any student what the motto was, not a single [one] could have told me four years ago,” Bock says. “Now if you ask, they all can tell you what the motto is, and the students bring that to everything we do,” including during rehearsals, at performances or just walking onto the field.

“It was at the top of every single paper, but when I asked any student what the motto was, not a single [one] could have told me four years ago,” Bock says. “Now if you ask, they all can tell you what the motto is, and the students bring that to everything we do,” including during rehearsals, at performances or just walking onto the field. Then, Bock created a leadership training program using developed techniques from authors and well-known music education advocates,

Then, Bock created a leadership training program using developed techniques from authors and well-known music education advocates,  With 250 students in a band program comprising four concert bands, four jazz bands, two woodwind choirs, a marching band (with about half of the students), two winter guards and a concert percussion ensemble, Bock believes that there are hands-on roles for at least 100 students.

With 250 students in a band program comprising four concert bands, four jazz bands, two woodwind choirs, a marching band (with about half of the students), two winter guards and a concert percussion ensemble, Bock believes that there are hands-on roles for at least 100 students. When students resist change, Bock is comfortable with letting them stick to the status quo. For example, Bock had considered assigning low brass instruments to students for greater efficiency, not realizing that they felt a special tradition with picking out their own, almost like a “Harry Potter” wand-selection moment, she says.

When students resist change, Bock is comfortable with letting them stick to the status quo. For example, Bock had considered assigning low brass instruments to students for greater efficiency, not realizing that they felt a special tradition with picking out their own, almost like a “Harry Potter” wand-selection moment, she says. Bock took over as head marching band director in 2020, and for the future, she hopes to build on the excitement of the Hawaii trip to get more students and parents involved in the program, perhaps by hosting a competition.

Bock took over as head marching band director in 2020, and for the future, she hopes to build on the excitement of the Hawaii trip to get more students and parents involved in the program, perhaps by hosting a competition.

Traditional RPG systems have three fundamental components: describe, decide and roll. To begin, the description is given by the

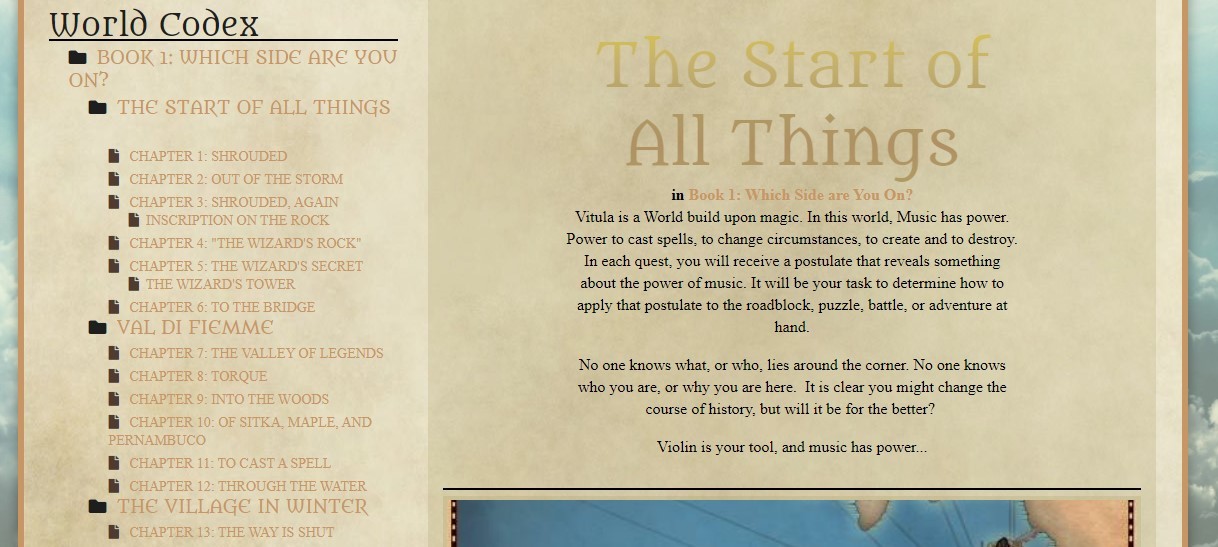

Traditional RPG systems have three fundamental components: describe, decide and roll. To begin, the description is given by the  Using an RPG to deliver my violin content and curriculum through a world of wizards and mystery was just the escape that my students and I needed. As RPGs are built from the perspective of the GM, it’s easy to manage a classroom while delivering the story and teaching the lesson. Because the RPG community is so welcoming, I found an incredible wealth of resources that helped a GM novice like me build a world my students connect with and allow me to deliver my curriculum effectively. It is easy to do, and the results are among the most rewarding I’ve experienced in my teaching career.

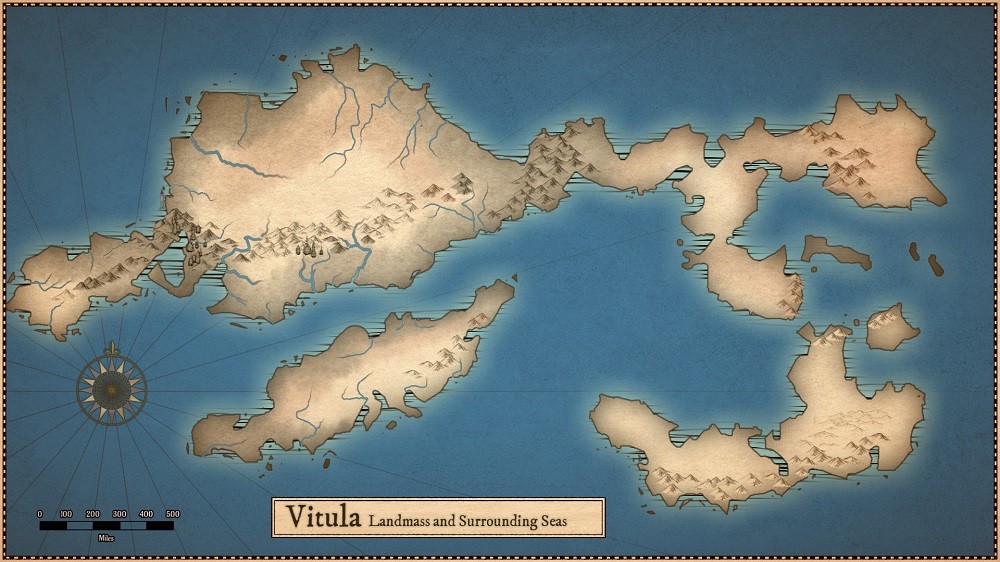

Using an RPG to deliver my violin content and curriculum through a world of wizards and mystery was just the escape that my students and I needed. As RPGs are built from the perspective of the GM, it’s easy to manage a classroom while delivering the story and teaching the lesson. Because the RPG community is so welcoming, I found an incredible wealth of resources that helped a GM novice like me build a world my students connect with and allow me to deliver my curriculum effectively. It is easy to do, and the results are among the most rewarding I’ve experienced in my teaching career. I named the world Vitula, which is the medieval Latin name for the group of instruments that ultimately became the violin family. In building the framework for Vitula, I needed a fantasy realm that allowed me to be spontaneous, creative and flexible. I love manipulatives and designing sets for theater, so I constructed a world that required diorama components to describe it. By incorporating digital elements, I connected the experience of the classroom with our online students to illustrate that they are integral in our community.

I named the world Vitula, which is the medieval Latin name for the group of instruments that ultimately became the violin family. In building the framework for Vitula, I needed a fantasy realm that allowed me to be spontaneous, creative and flexible. I love manipulatives and designing sets for theater, so I constructed a world that required diorama components to describe it. By incorporating digital elements, I connected the experience of the classroom with our online students to illustrate that they are integral in our community. The first two years (known as “books”) of the story are completed. Book 1, entitled “Which Side Are You On?,” introduces the conflicts, factions and varying perspectives of individuals within Vitula. Students interact with fictionalized versions of musical figures and locations, including Val di Fieme, Ole Bull, Il Canone and the wizard Orlandini (named after an Italian luthier).

The first two years (known as “books”) of the story are completed. Book 1, entitled “Which Side Are You On?,” introduces the conflicts, factions and varying perspectives of individuals within Vitula. Students interact with fictionalized versions of musical figures and locations, including Val di Fieme, Ole Bull, Il Canone and the wizard Orlandini (named after an Italian luthier). credibly populate my world. I did not pick specific characters that already existed because I wanted the freedom to develop my own.

credibly populate my world. I did not pick specific characters that already existed because I wanted the freedom to develop my own. When all of this is achieved, the true power of the RPG is unleashed. By using an RPG in the classroom, I share about our real world and teach music in a way that builds wonder, respect and joy as well as increases skill level. It feels great to finally hear a beginning violinist plead, “Mr. Gamon, will you please teach me to play a scale?”

When all of this is achieved, the true power of the RPG is unleashed. By using an RPG in the classroom, I share about our real world and teach music in a way that builds wonder, respect and joy as well as increases skill level. It feels great to finally hear a beginning violinist plead, “Mr. Gamon, will you please teach me to play a scale?”

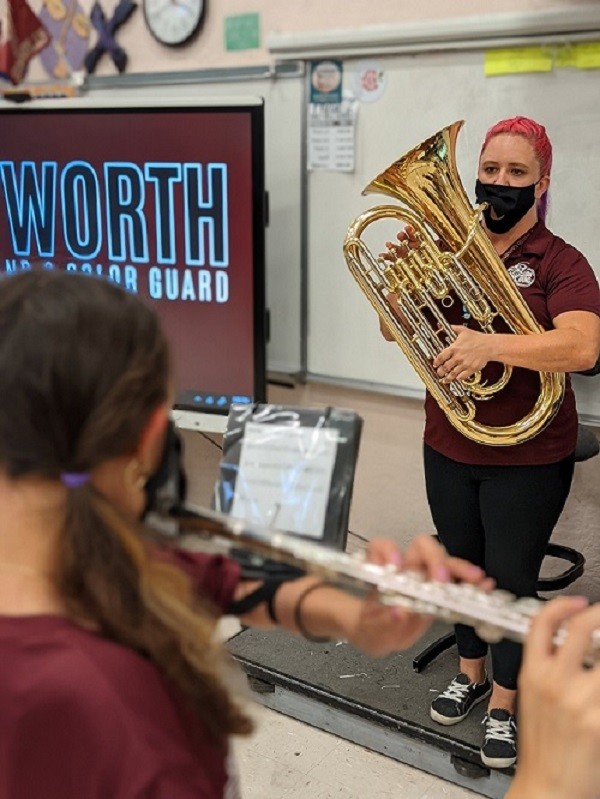

Switching flutes to French horns, on the other hand, works quite well. Here’s why:

Switching flutes to French horns, on the other hand, works quite well. Here’s why:

Before you have flute students play horn in band, allow them to take a loaner home and try it out for a week or two. This will prevent them from feeling lost in the middle of a rehearsal. When the time comes, be direct with your class and mention the switch during announcements. This will keep classroom management in check and prevent any whisperings of “Why is Susan on the horn now?!”

Before you have flute students play horn in band, allow them to take a loaner home and try it out for a week or two. This will prevent them from feeling lost in the middle of a rehearsal. When the time comes, be direct with your class and mention the switch during announcements. This will keep classroom management in check and prevent any whisperings of “Why is Susan on the horn now?!”

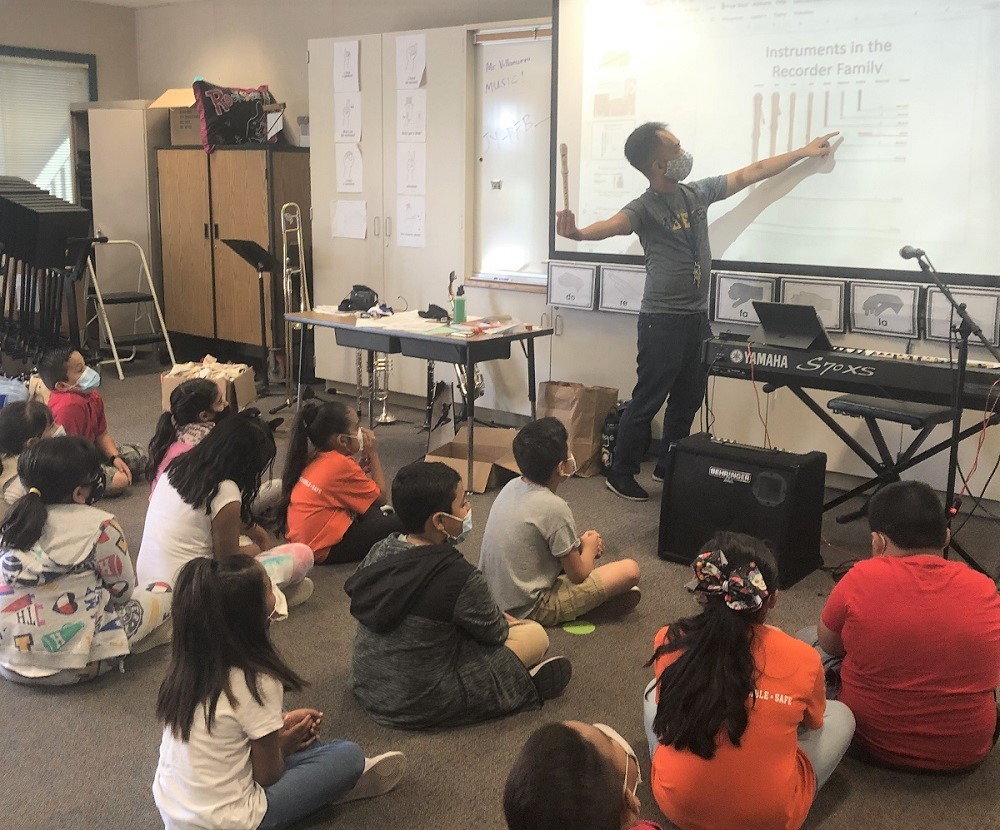

Villanueva, who graduated with dual bachelor’s degrees in music education and jazz studies from

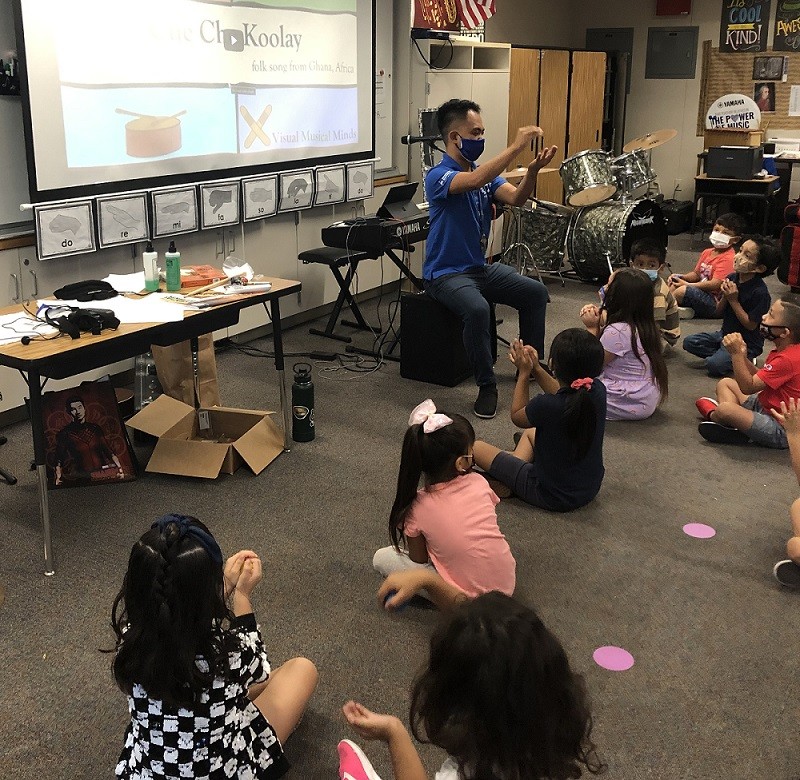

Villanueva, who graduated with dual bachelor’s degrees in music education and jazz studies from  Villanueva teaches all 600 students at Orange Grove. Each grade is divided into several classes that meet for 30 minutes per week for TK and 1st grade, 45 minutes for 2nd through 4th grades, and 90 minutes for 5th and 6th grades. During the 2020-2021 academic year when the entire school was virtual until April, he met with 6th graders twice per week.

Villanueva teaches all 600 students at Orange Grove. Each grade is divided into several classes that meet for 30 minutes per week for TK and 1st grade, 45 minutes for 2nd through 4th grades, and 90 minutes for 5th and 6th grades. During the 2020-2021 academic year when the entire school was virtual until April, he met with 6th graders twice per week. Villanueva specifically wanted melodicas, a combination wind instrument and keyboard, for younger grades. “I got the idea of incorporating melodicas after seeing some videos of children in Japan,” he says. “Plus, it’s louder than electronic keyboards, so for performance purposes, it’s great to project. It’s also a good segue into 5th grade and 6th grade when students have to learn to use their air. Not only are they developing keyboard skills, but they’re also learning breathing skills.”

Villanueva specifically wanted melodicas, a combination wind instrument and keyboard, for younger grades. “I got the idea of incorporating melodicas after seeing some videos of children in Japan,” he says. “Plus, it’s louder than electronic keyboards, so for performance purposes, it’s great to project. It’s also a good segue into 5th grade and 6th grade when students have to learn to use their air. Not only are they developing keyboard skills, but they’re also learning breathing skills.” In past years, Orange Grove students participated in the

In past years, Orange Grove students participated in the  Villanueva brings more and more new ideas to his classes because he is constantly learning through his recent master’s program as well as during freelance gigs, professional development classes such as Little Kids Rock educational events, and side work with the

Villanueva brings more and more new ideas to his classes because he is constantly learning through his recent master’s program as well as during freelance gigs, professional development classes such as Little Kids Rock educational events, and side work with the

To help with YCCT’s launch, we selected an eclectic board of directors with a passion for children’s singing. Current board members include local public-school music teachers, Baylor music education faculty members, parents, choral musicians and community advocates. We also employ a business manager (CPA) and have an attorney who volunteers advice when called upon.

To help with YCCT’s launch, we selected an eclectic board of directors with a passion for children’s singing. Current board members include local public-school music teachers, Baylor music education faculty members, parents, choral musicians and community advocates. We also employ a business manager (CPA) and have an attorney who volunteers advice when called upon. Interns act as small group facilitators for practice pods. Older choristers are spaced strategically among younger singers to ensure all have helpers nearby to aid with tasks like finding their place on the printed page, marking scores and, most importantly, providing a vocal support and encouragement. We are aware of when and how we employ the use of the “surrogate” teacher.

Interns act as small group facilitators for practice pods. Older choristers are spaced strategically among younger singers to ensure all have helpers nearby to aid with tasks like finding their place on the printed page, marking scores and, most importantly, providing a vocal support and encouragement. We are aware of when and how we employ the use of the “surrogate” teacher. One thing we have discovered is that if the older singers are always asked to serve as models for their younger peers, their own needs are not served. Therefore, we ask the collegiate interns to model for the older chorus and, in turn, the staff models vocal and teaching techniques for the interns. Each rehearsal begins and ends with a brief staff meeting and debriefing that especially focuses on interns’ needs and questions.

One thing we have discovered is that if the older singers are always asked to serve as models for their younger peers, their own needs are not served. Therefore, we ask the collegiate interns to model for the older chorus and, in turn, the staff models vocal and teaching techniques for the interns. Each rehearsal begins and ends with a brief staff meeting and debriefing that especially focuses on interns’ needs and questions.

Upgrade the Sound System

Upgrade the Sound System Once your phone or tablet is connected to a sound system via Bluetooth, you can utilize your phone’s voice memo taker as a recording and playback station for your classroom. Record a difficult passage with your phone and play the recording back while speaking directly to the students who need your help. Moving the phone around the room will allow you to capture the moments that the students may not be hearing. For instance, recording close to the students who are out of tune might help you segue into the importance of listening and tuning without calling out specific students. Let the recording be the bad guy.

Once your phone or tablet is connected to a sound system via Bluetooth, you can utilize your phone’s voice memo taker as a recording and playback station for your classroom. Record a difficult passage with your phone and play the recording back while speaking directly to the students who need your help. Moving the phone around the room will allow you to capture the moments that the students may not be hearing. For instance, recording close to the students who are out of tune might help you segue into the importance of listening and tuning without calling out specific students. Let the recording be the bad guy.

Apart from technology, seating and staging have a large impact on how students act in the music room. Though traditional seating is important for posture and performance, is there space in your room for a non-traditional seating area?

Apart from technology, seating and staging have a large impact on how students act in the music room. Though traditional seating is important for posture and performance, is there space in your room for a non-traditional seating area? Elementary music classrooms utilize yoga balls, buckets and even

Elementary music classrooms utilize yoga balls, buckets and even

Depending on your school setting and policies, the simplest solution is to open a window or door if you possibly can — even for short periods during cold-weather months. (Be sure the window is screened and or secured in a way that it will not create a fall risk for students.)

Depending on your school setting and policies, the simplest solution is to open a window or door if you possibly can — even for short periods during cold-weather months. (Be sure the window is screened and or secured in a way that it will not create a fall risk for students.) Beyond simple fresh air, consider what else students might be inhaling and strive for a cleaner indoor space.

Beyond simple fresh air, consider what else students might be inhaling and strive for a cleaner indoor space.

One week, I taught 10 classes the same singing game called “

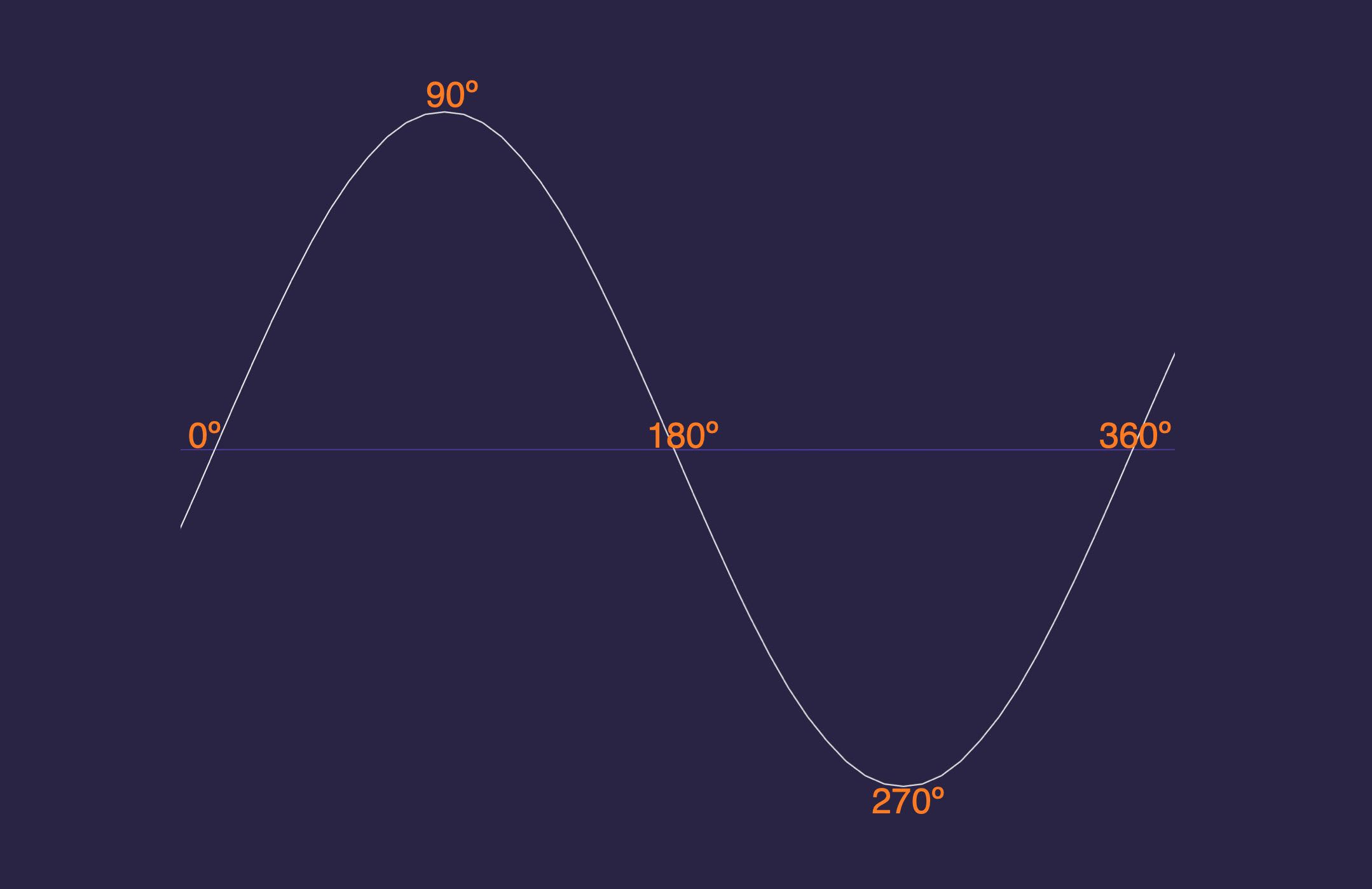

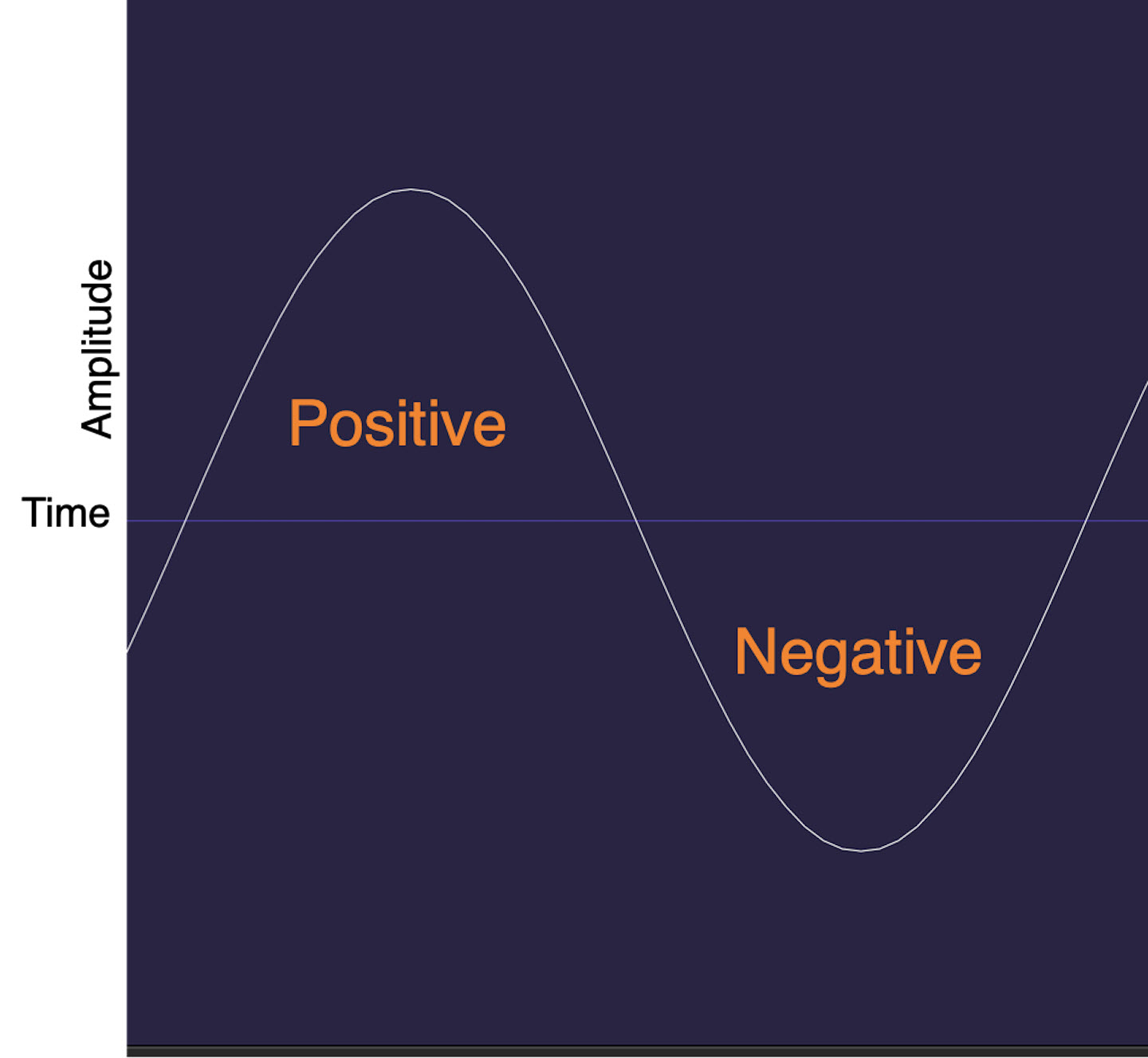

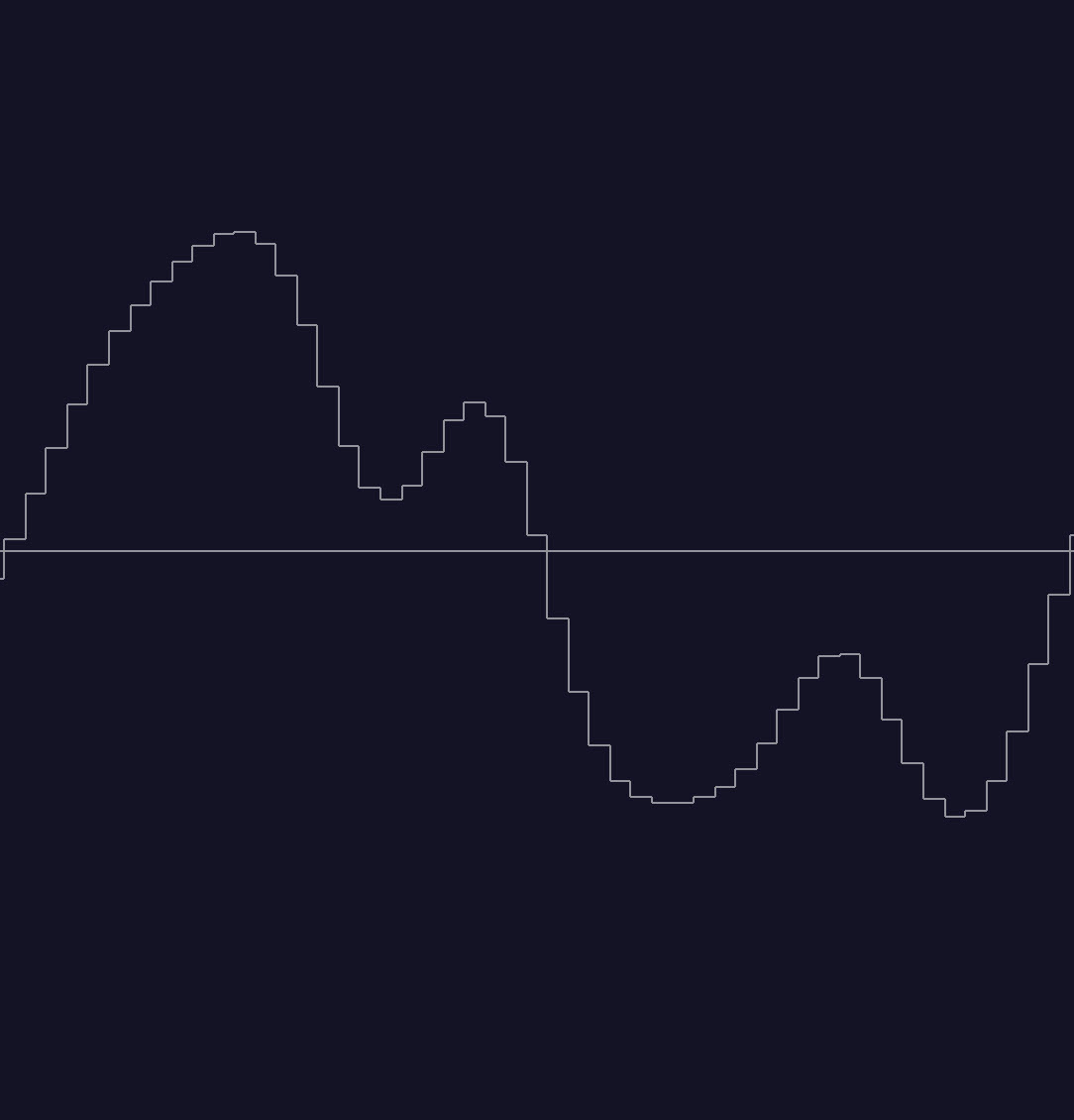

One week, I taught 10 classes the same singing game called “ What helped me become more confident was understanding the science about voice and sound. I never enjoyed hearing my singing or speaking voice, and I learned that there was a reason for this. It’s called voice confrontation.

What helped me become more confident was understanding the science about voice and sound. I never enjoyed hearing my singing or speaking voice, and I learned that there was a reason for this. It’s called voice confrontation.

I bought a tripod for my cell phone and a green blanket so I could record instruments and remove the background on the computer. That was all I needed to make a majority of my instrument lesson videos.

I bought a tripod for my cell phone and a green blanket so I could record instruments and remove the background on the computer. That was all I needed to make a majority of my instrument lesson videos. Seeing the views go up on a new or even an old lesson gives me a sense of gratification that I can’t get anywhere else. I really enjoy the recent vlogging because teachers need to know that they are not the only professionals experiencing this era of COVID music education. I received a comment that said, “I needed to hear this,” which was all I needed to know that it was time well spent.

Seeing the views go up on a new or even an old lesson gives me a sense of gratification that I can’t get anywhere else. I really enjoy the recent vlogging because teachers need to know that they are not the only professionals experiencing this era of COVID music education. I received a comment that said, “I needed to hear this,” which was all I needed to know that it was time well spent.

Our initial step was to have students learn a short etude that was well within their ability level for a pass-off due on a certain date. We told the students that they collectively had to decide benchmark dates prior to the due date and how much of the etude needed to be learned and performed by those benchmarks. This is where we left it as we wanted the ownership of their backward planning to be solely on them.