Today’s Tasks that Pay off in May

Music education has always been about the long game and less about the quick wins. While instant gratification can be enticing, I’ll always choose the joy of long-term accomplishments. Here’s how you can set up your class for lifelong success.

Always Address Tone

We’re always swamped during rehearsal, but if we wrap up early, it’s back to tone. Think of it as building musical athleticism. Forming an embouchure, holding a bow or singing with proper breath support is physical. The mechanics of good tone involve real muscle and airflow. No shortcuts allowed.

Treat your musicians like athletes and understand that if you want great tone at the spring concert, then you must start your physical conditioning now. Rushing this process isn’t just ineffective, it’s potentially damaging to the musicians’ physical wellbeing. So, plan accordingly, and commit to the long game of developing tone.

Try These Practical Tips

- Play or sing for your students regularly; let them hear it straight from you.

- Use online resources, but don’t just settle for anything. Find a credible source, such as university or professional recordings, and stick with it. I like to use either the Bravo Music’s Winds Training Series DVDs or the London Symphony Orchestra YouTube videos.

- Work breathing exercises into your daily routine. Tone starts with air.

Insist on Intonation

We focus on intonation from the first day of class, and in many instances, we begin during the summer through extra rehearsals. Without this early commitment, my ensemble will not be able to perform in tune effectively. The process is layered — first, we work on achieving a characteristic tone, followed by addressing balance among the instruments. Only then do we dive into the specifics of tuning unison pitches.

There’s a camp of people who argue against using electronic tuners, advocating instead for “listening.” While I’m a big proponent of developing listening skills, I see the value in attaching tuners to each student’s instrument, especially during the early phases of rehearsal. My ears may not be perfect, but they’re still more trained than those of the students. Consequently, they often don’t know what good intonation sounds like until we collectively produce it and internalize that sound. It becomes a lightbulb moment when I can get just two students to play in tune, which gives them a benchmark, a goal.

By the time December rolls around, the majority of students have a tangible understanding of what “in tune” really means. Why the push to start so early? We’re back to our musical athletes. Certain muscular techniques — like tightening or relaxing the embouchure to alter pitch — require time to develop. These are not skills that can be rushed without risking poor habits or even physical strain. Therefore, an early start on intonation is crucial.

Try These Practical Tips

- Utilize the resources at your disposal: employ tuners, drones and other tools to refine pitch.

- Conduct a pitch inventory in pairs for targeted improvement. Designate a space like a practice room where two students can bring their instruments, a tuner and a note sheet. One student plays while the other observes the tuner and records the pitch accuracy — sharp, flat or in tune. This exercise makes students aware of their individual pitch tendencies.

- Incorporate specialized tools like tonal harmony software or the Yamaha Harmony Director to teach intonation. Pairing these resources with instructional materials like the Bravo Music’s Winds Training Series DVDs can enhance learning.

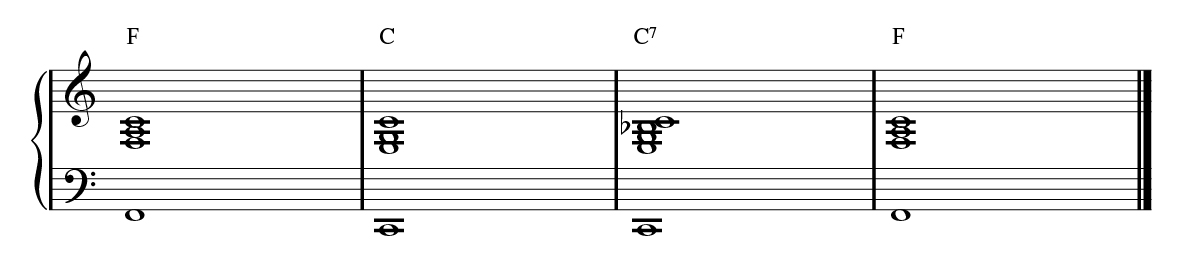

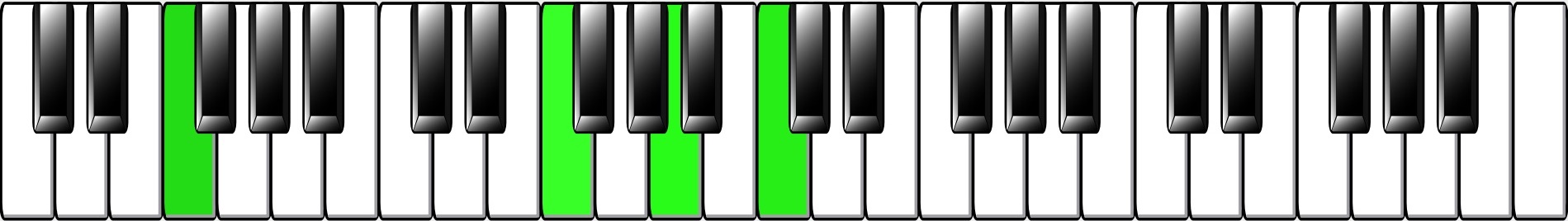

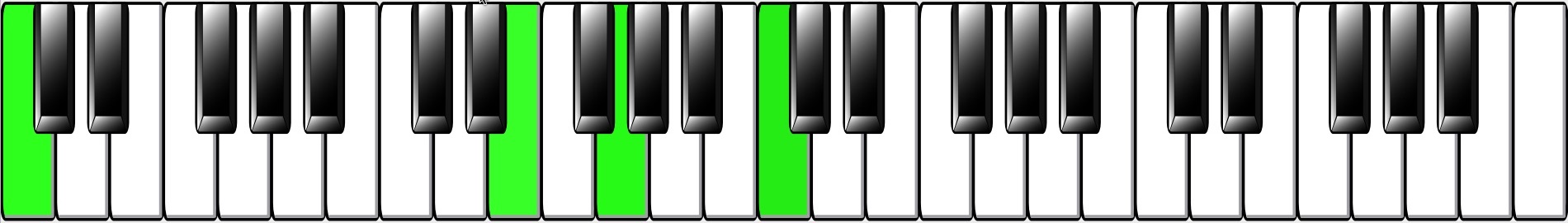

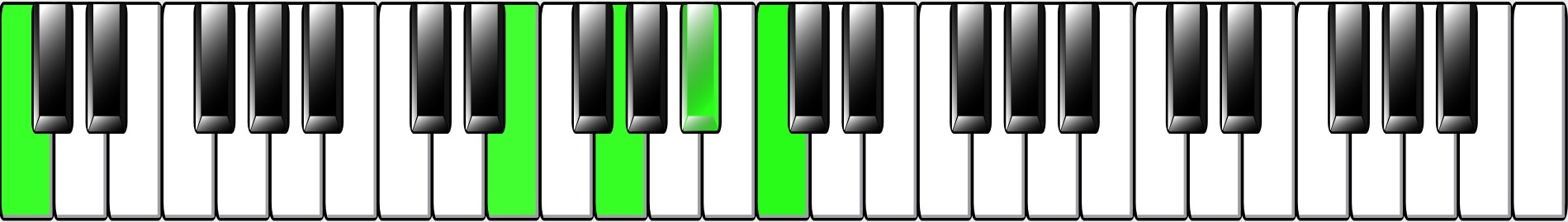

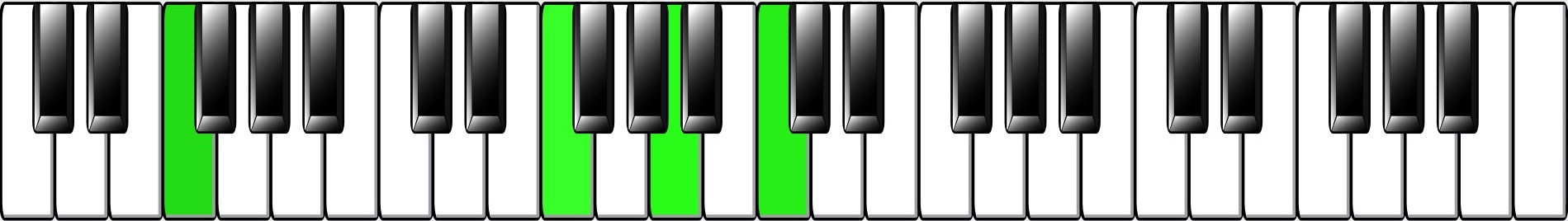

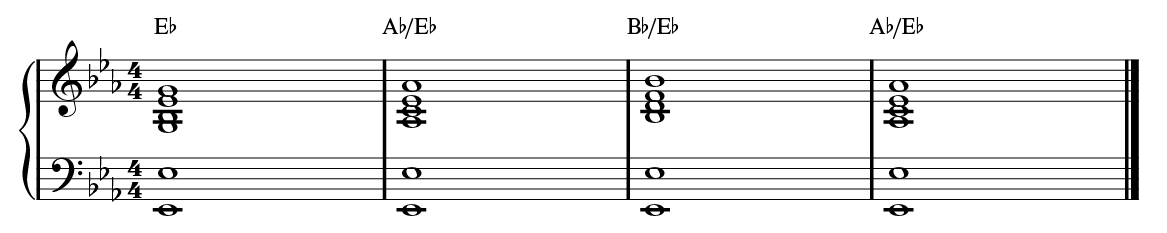

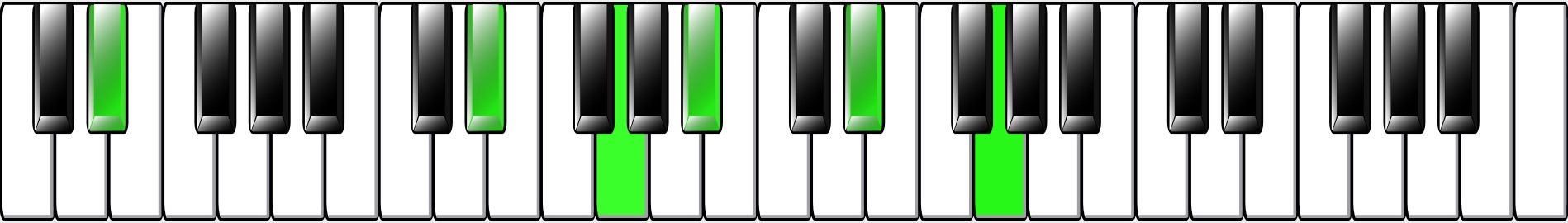

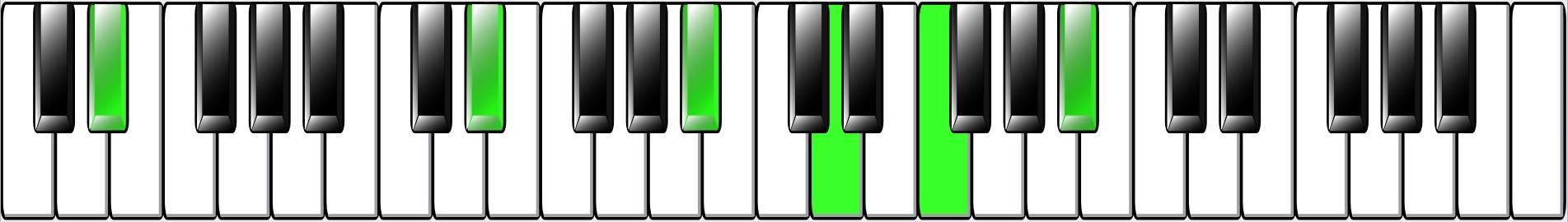

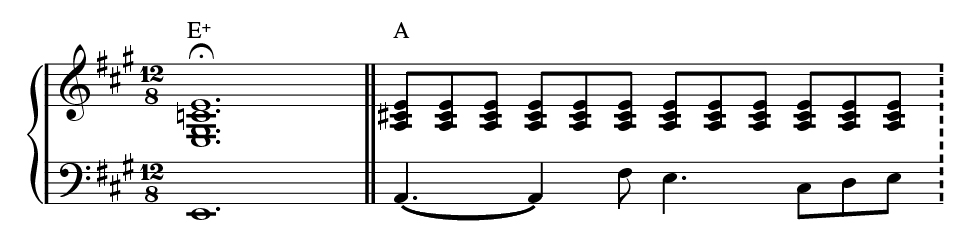

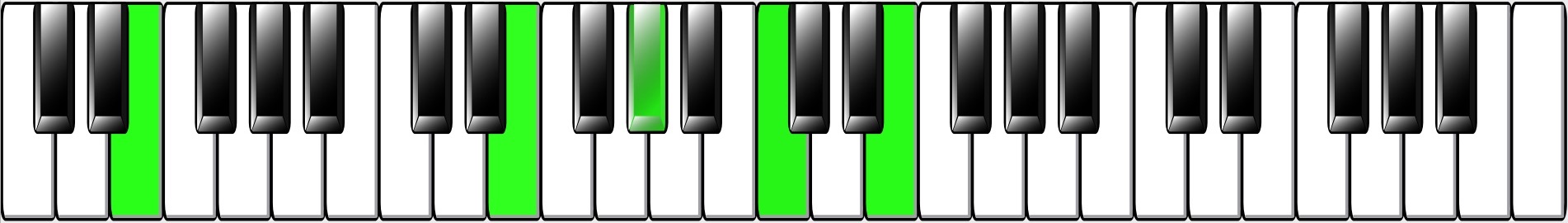

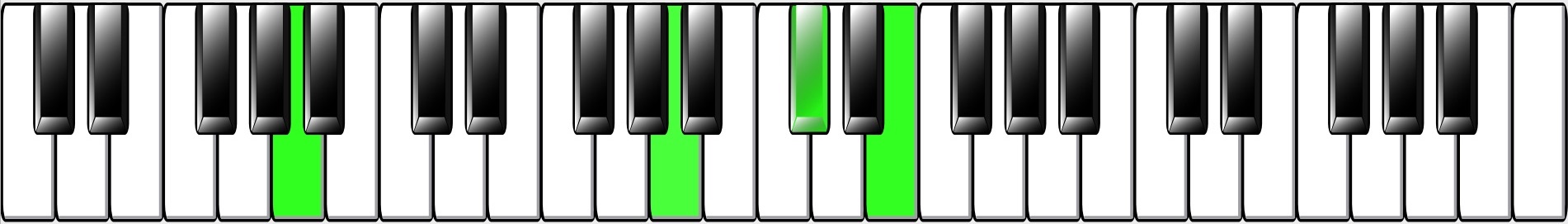

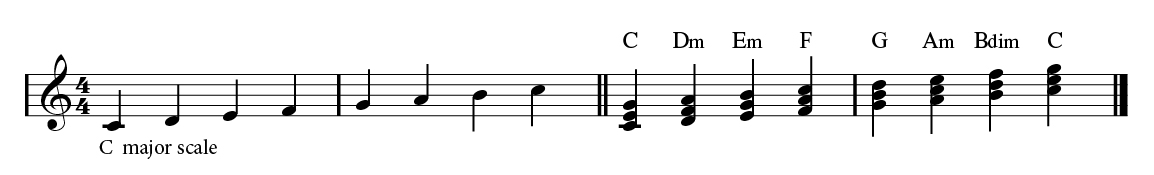

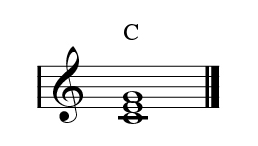

- Start by tuning a single pitch each day and then progress to tuning an entire chord daily. This gradual approach helps students better understand what being “out of tune” really means.

- Use the “two tuners trick” to improve pitch perception: Set up two tuners to produce a tone simultaneously, one at 430 hz and the other at 440 hz. Gradually increase the frequency on one tuner by one hertz at a time. Have students raise their hands when they no longer hear the wavy sound produced by the conflicting pitches. This exercise is effective in teaching students to recognize out-of-tune waves.

Start Sightreading Every Day

Encourage your students to sightread a new piece of music every day. I know that time is a constraint. However, the dividends of consistent, daily sightreading are invaluable.

Investing in sightreading during the fall months — October, November, December — eases the fears and anxieties your musicians might have about new music come January and February. The task becomes less daunting, and your students will eagerly take on new pieces. Plus, incorporating regular sightreading into your routine can serve as a refreshing change of pace, breaking up the potential monotony of lengthy concert preparation cycles.

Try These Practical Tips

- Start small: Dedicate one day a week as sightreading day or focus on one new piece a week over multiple days. Aim to increase the frequency over time.

- Utilize resources: Tap into sightreading books or methods, whether from print or digital retailers. Most books, such as Tradition of Excellence or Essential Elements, provide some sightreading or rhythm reading examples in the back. If you use MakeMusic (formerly SmartMusic) or Musicfirst, the sightreading examples they supply will work well.

- Switch it up: Have musicians swap parts. For example, part 1 can play part 2, part 2 can play part 3 and so on. Trumpets might tackle clarinet parts (adjusting for range) and vice versa. Get creative — there’s no one-size-fits-all approach to help students improve.

Maintenance Matters

I drive a 2003 Toyota that has its share of minor issues, but it’s a reliable vehicle overall. While I’m no car expert, I address mechanical problems as they arise and prioritize preventive maintenance. Given that I’m driving an older model, I understand the importance of frequent oil checks and having a professional inspect various components like tires and spark plugs every so often.

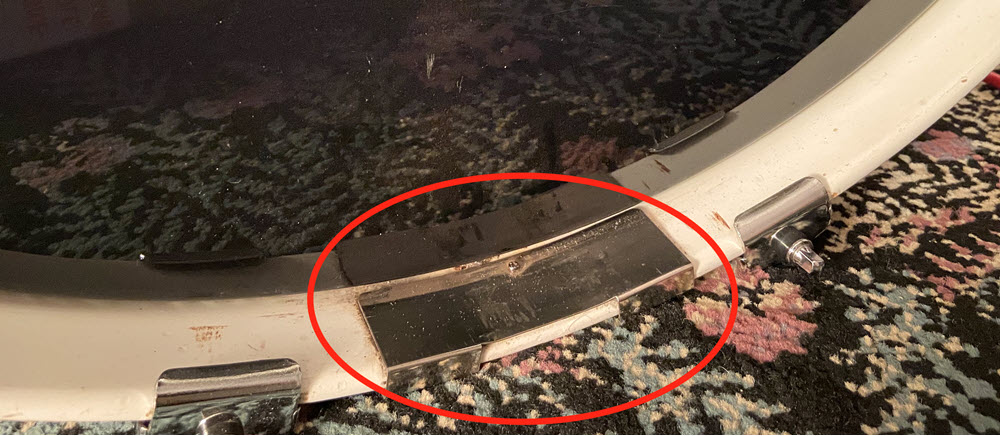

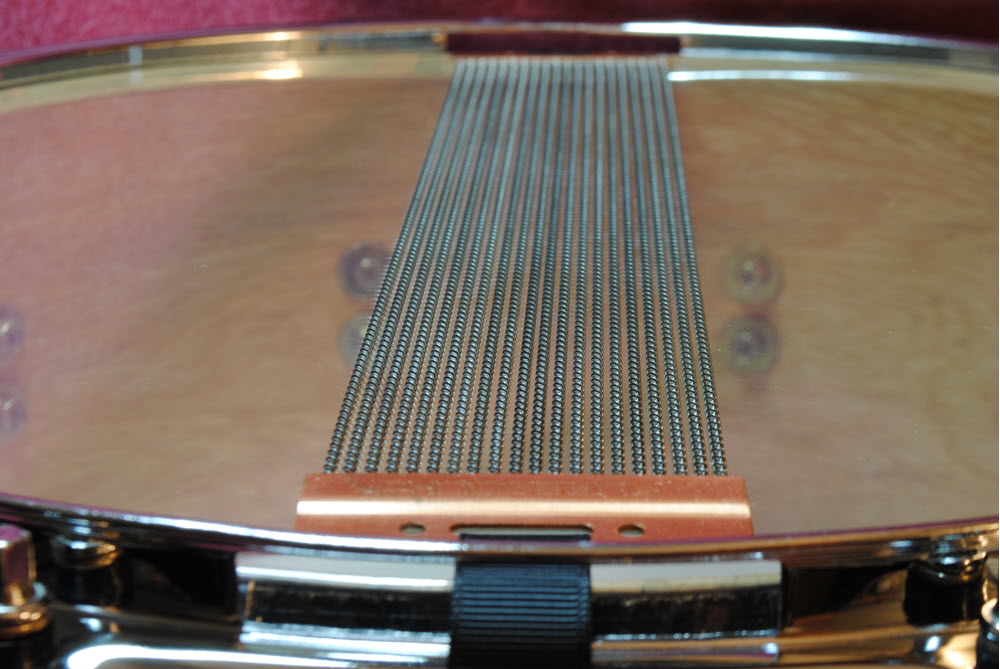

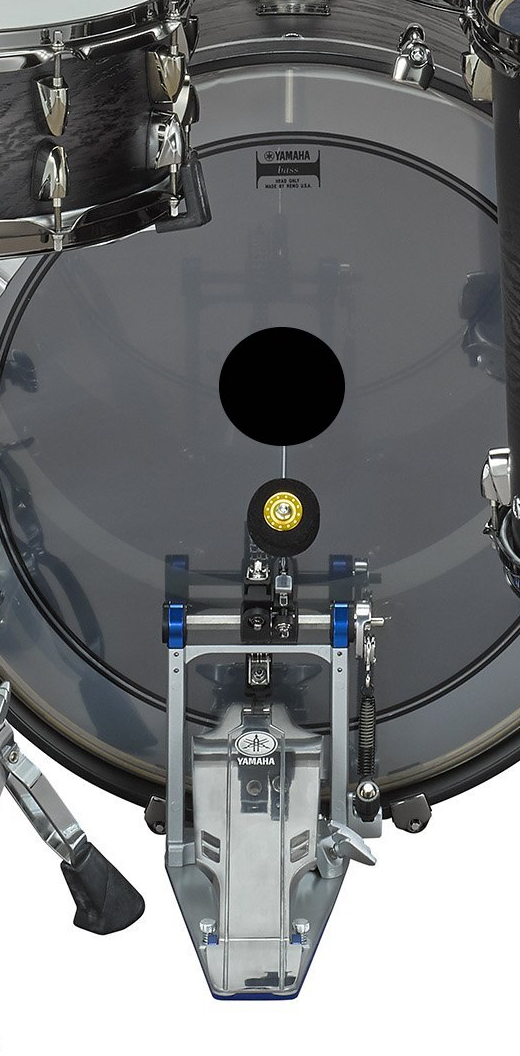

In the same vein, maintaining our musical instruments — and yes, that includes voices — instills discipline and responsibility in our students. It also minimizes unpleasant surprises, like a clarinet spring breaking just moments before a performance. Take time during class to remind students to oil and grease their instruments regularly. For vocalists, emphasize the importance of vocal rest, staying hydrated and avoiding straining activities like screaming, whispering or even speaking loudly.

Try These Practical Tips

- Keep a visible chart with a maintenance schedule for instruments so everyone knows when it’s time for a tune-up.

- Reach out to parents or, even better, partner with an instrument repair company to send technicians for periodic check-ups, akin to doctor’s visits.

- Incorporate a quick “health check” at the beginning of each week’s practice. Have students do a basic rundown of their instruments or vocal cords, noting any issues like sticking valves or vocal strain, so they can be addressed before they become larger problems.

Facing Fears

I don’t mean to get psychological here, but I know from conversations with colleagues that a lot of us have things that we’re either afraid of or that we simply avoid. Maybe you’re hesitant to focus on a difficult music section, reluctant to rehearse an unpopular piece or nervous about asking for more funding. Do your due diligence — know your facts and prepare accordingly. Then, get real with yourself: Make a list of what you’re avoiding. Depending on your comfort level and the stakes involved, you can either approach these issues cautiously or jump in with both feet.

I had my own set of fears — inviting clinicians (too soon, we’re not ready), isolating sections or individuals during practice (I don’t want to single anyone out, we’re too busy), and petitioning for additional funding (it’s a tight budget, they’ll likely refuse). Recognizing these fears was a game changer; ignoring them was no longer an option. Facing them head-on has improved me and my ensemble.

Try These Practical Tips

- Carve out some time to reflect on what you tend to avoid during rehearsals. Write down your reasons for avoiding these things. Next, ask yourself if others are doing these things and succeeding. If so, question why you think you can’t. Keep in mind that we often see what we expect to see when looking at others’ situations — not the whole truth.

- Depending on your personality, try a different approach to confronting these issues. If you’re usually hesitant, try diving right into a smaller task. If you’re the type to act quickly, maybe slow down and think it through before taking action.

- Regularly reassess your list of fears or avoidances. Once you’ve tackled one, it’s easy to replace it with another one without even noticing. A periodic review ensures that you’re constantly evolving, both as an educator and as a musician.

Creating:

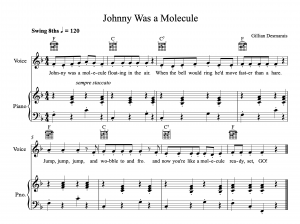

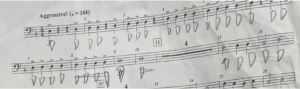

Creating: Edit in notation software (like

Edit in notation software (like

1) Begin with the question, “what is sound?” As students guess, slowly navigate them toward the answer: “vibrations in the air.” Next ask, “What is actually vibrating when we hear sound?” The answer should be “air molecules.” Feel free to use the following explanations below alongside diagrams or photos in a slideshow presentation.

1) Begin with the question, “what is sound?” As students guess, slowly navigate them toward the answer: “vibrations in the air.” Next ask, “What is actually vibrating when we hear sound?” The answer should be “air molecules.” Feel free to use the following explanations below alongside diagrams or photos in a slideshow presentation.

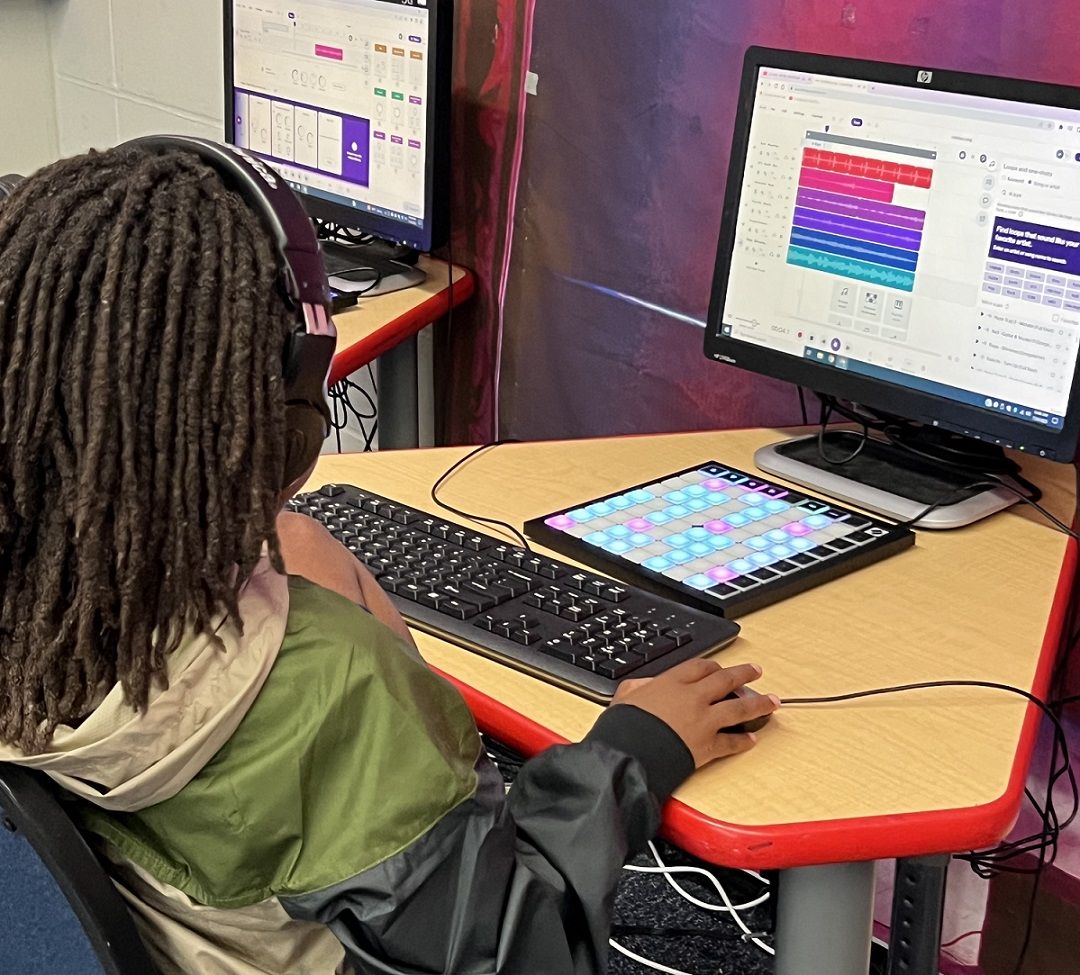

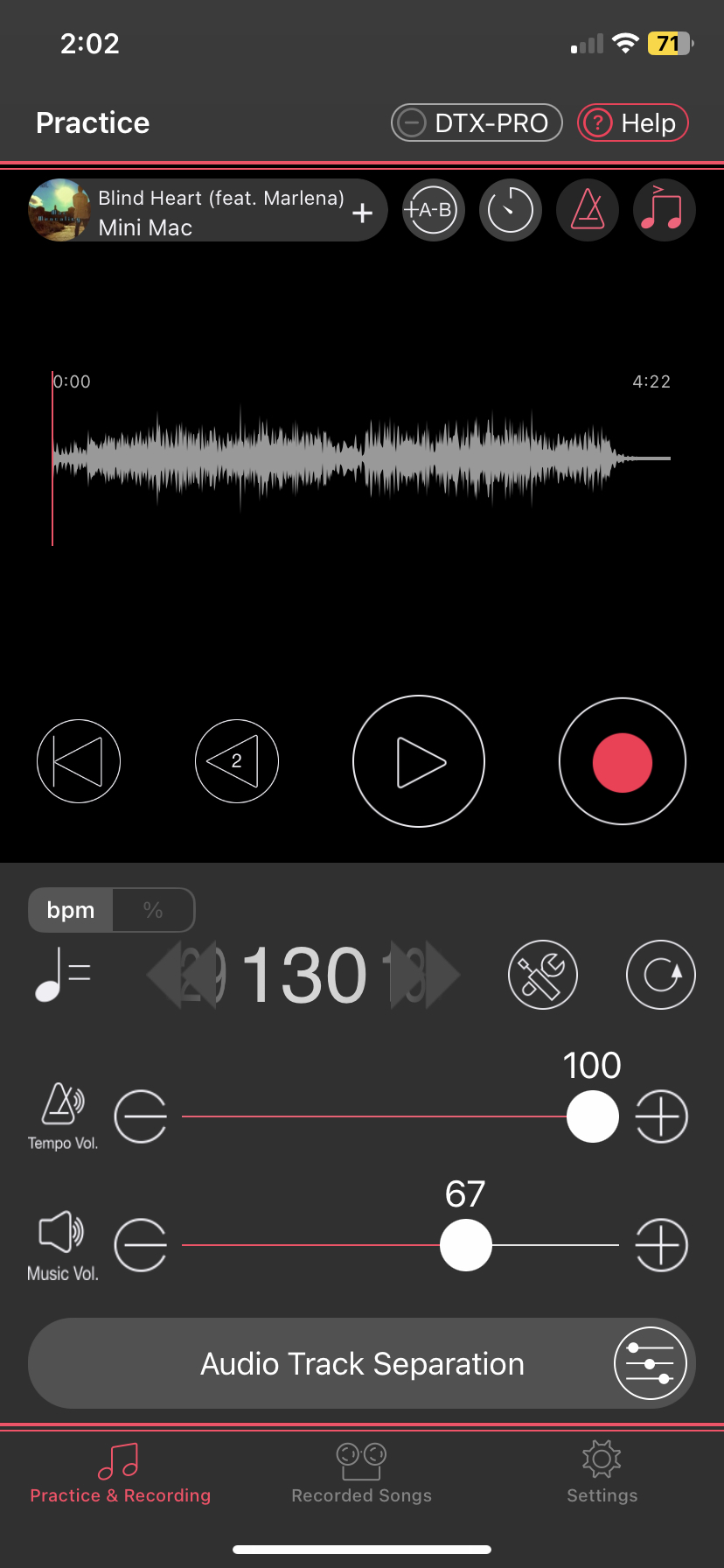

2) Have a project open in your DAW and encourage students to view the sample browser/loop browser. From here, differentiate audio loops by their “audio icon” (see below) and drag and drop one into the timeline. See some examples below for reference.

2) Have a project open in your DAW and encourage students to view the sample browser/loop browser. From here, differentiate audio loops by their “audio icon” (see below) and drag and drop one into the timeline. See some examples below for reference.

I would like to begin this series by sharing what is one of the core tenets of building and sustaining school music programs: recruitment. As a music educator in the age of data-driven decision making, I have tried to leverage administrator demands for data by providing evidence of how students, parents and staff make the program shine, as outlined in Roger Mantie’s “

I would like to begin this series by sharing what is one of the core tenets of building and sustaining school music programs: recruitment. As a music educator in the age of data-driven decision making, I have tried to leverage administrator demands for data by providing evidence of how students, parents and staff make the program shine, as outlined in Roger Mantie’s “ Recruitment has no real beginning or end. It is a continuous process fueled by active recruiting strategies, culturally relevant curricula and student ownership of the process, according to Daniel J. Albert’s “

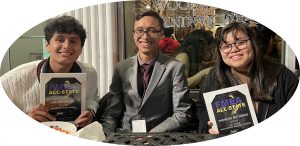

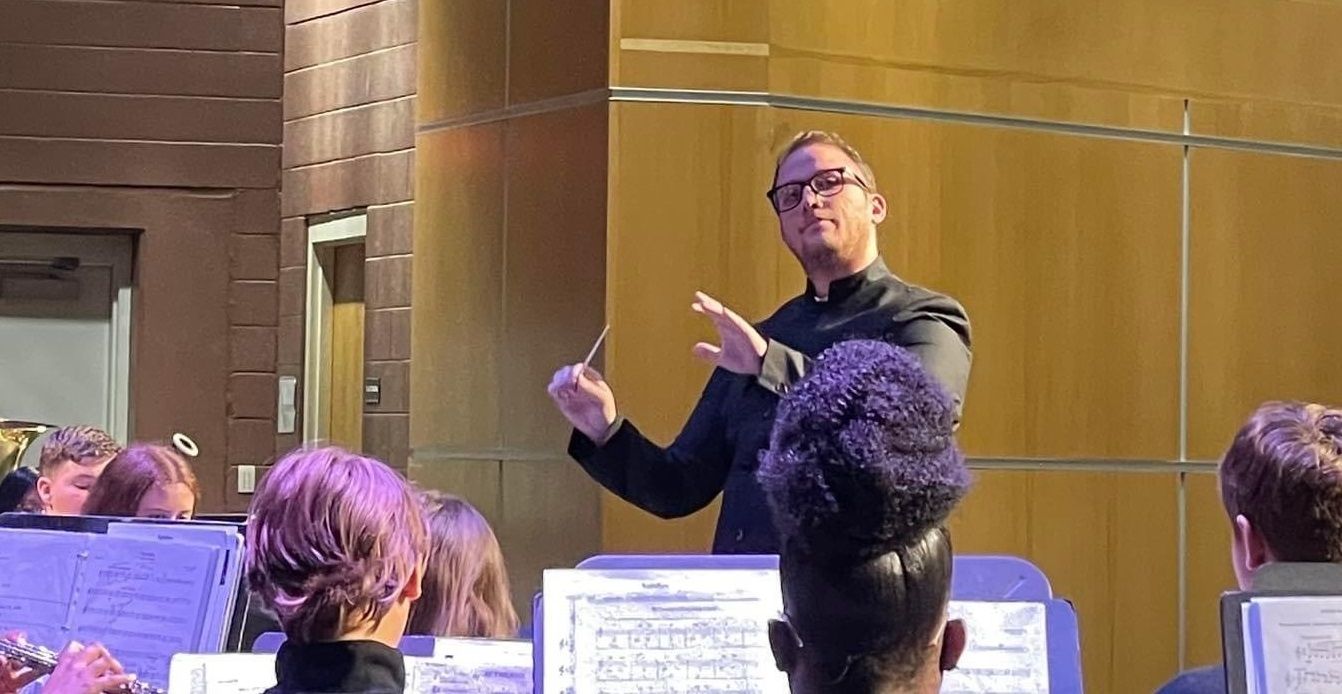

Recruitment has no real beginning or end. It is a continuous process fueled by active recruiting strategies, culturally relevant curricula and student ownership of the process, according to Daniel J. Albert’s “ Performance is a great way to showcase your students’ abilities, and it also serves as a chance to connect with potential recruits. Whether we performed at a sporting event, seasonal concert, performance assessment or a community event, I always made sure to provide space for recruiting. Students shared their experiences in the music program, and I had flyers, handouts and contact information ready to give out to students and parents who might be interested in signing up.

Performance is a great way to showcase your students’ abilities, and it also serves as a chance to connect with potential recruits. Whether we performed at a sporting event, seasonal concert, performance assessment or a community event, I always made sure to provide space for recruiting. Students shared their experiences in the music program, and I had flyers, handouts and contact information ready to give out to students and parents who might be interested in signing up. There are several ways to look at and set your enrollment targets. Some look at what percentage of the total school population is enrolled in a particular program, while others look at numbers of new recruits versus retention of prior classes. And there are still others who look at historic trends and set targets based on those.

There are several ways to look at and set your enrollment targets. Some look at what percentage of the total school population is enrolled in a particular program, while others look at numbers of new recruits versus retention of prior classes. And there are still others who look at historic trends and set targets based on those.

You can’t rush the good stuff. Whether you’re waiting for the ensemble to gel or for that one kid to finally get it — patience is key. Many of my mentors echoed this sentiment. And trust me, those seeds you’re planting? They will grow. You just have to give them time.

You can’t rush the good stuff. Whether you’re waiting for the ensemble to gel or for that one kid to finally get it — patience is key. Many of my mentors echoed this sentiment. And trust me, those seeds you’re planting? They will grow. You just have to give them time. This was a quote that my college band director, Dr. Charles Menghini, said in passing that I’ve never forgotten. “Sometimes the money’s not in the budget, but that doesn’t mean it’s not out there.”

This was a quote that my college band director, Dr. Charles Menghini, said in passing that I’ve never forgotten. “Sometimes the money’s not in the budget, but that doesn’t mean it’s not out there.” Give your students some skin in the game by letting them help select pieces or lead warm-ups. When I started incorporating student input, the atmosphere shifted from “us vs. them” to “we’re in this together.” And the best part was that performances were better for it. Besides, I’m the only director at my school, and I need the help!

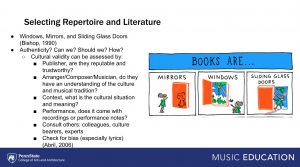

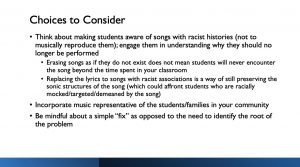

Give your students some skin in the game by letting them help select pieces or lead warm-ups. When I started incorporating student input, the atmosphere shifted from “us vs. them” to “we’re in this together.” And the best part was that performances were better for it. Besides, I’m the only director at my school, and I need the help! What you choose to play shapes not just the musical experience for your students, but also their emotional and intellectual development. What we play may be the most important curricular decision we make. And sometimes it’s also OK to program things that the kids like! Keep an ear out for what your kids warm-up on before rehearsal begins, and you instantly will know what works.

What you choose to play shapes not just the musical experience for your students, but also their emotional and intellectual development. What we play may be the most important curricular decision we make. And sometimes it’s also OK to program things that the kids like! Keep an ear out for what your kids warm-up on before rehearsal begins, and you instantly will know what works. This is an original: Complain about something twice, and you either need to fix it or let it go. It’s a principle that has served me well and has kept the rehearsal room positive and proactive.

This is an original: Complain about something twice, and you either need to fix it or let it go. It’s a principle that has served me well and has kept the rehearsal room positive and proactive. I catch myself with this one. If you’re using the word “should” too much, you’re not in the moment, and that’s a problem. Or, you have not accepted either what your situation is or where your control may be. I learned early on to adapt, reassess and keep it moving. “We shouldn’t have to invite the principal to our concert — they should just attend!” This, and other items, are not always how things work.

I catch myself with this one. If you’re using the word “should” too much, you’re not in the moment, and that’s a problem. Or, you have not accepted either what your situation is or where your control may be. I learned early on to adapt, reassess and keep it moving. “We shouldn’t have to invite the principal to our concert — they should just attend!” This, and other items, are not always how things work. Good or bad, tomorrow is another chance. Each new day presents a clean slate to try again, to be better, to make music. Embrace it.

Good or bad, tomorrow is another chance. Each new day presents a clean slate to try again, to be better, to make music. Embrace it.

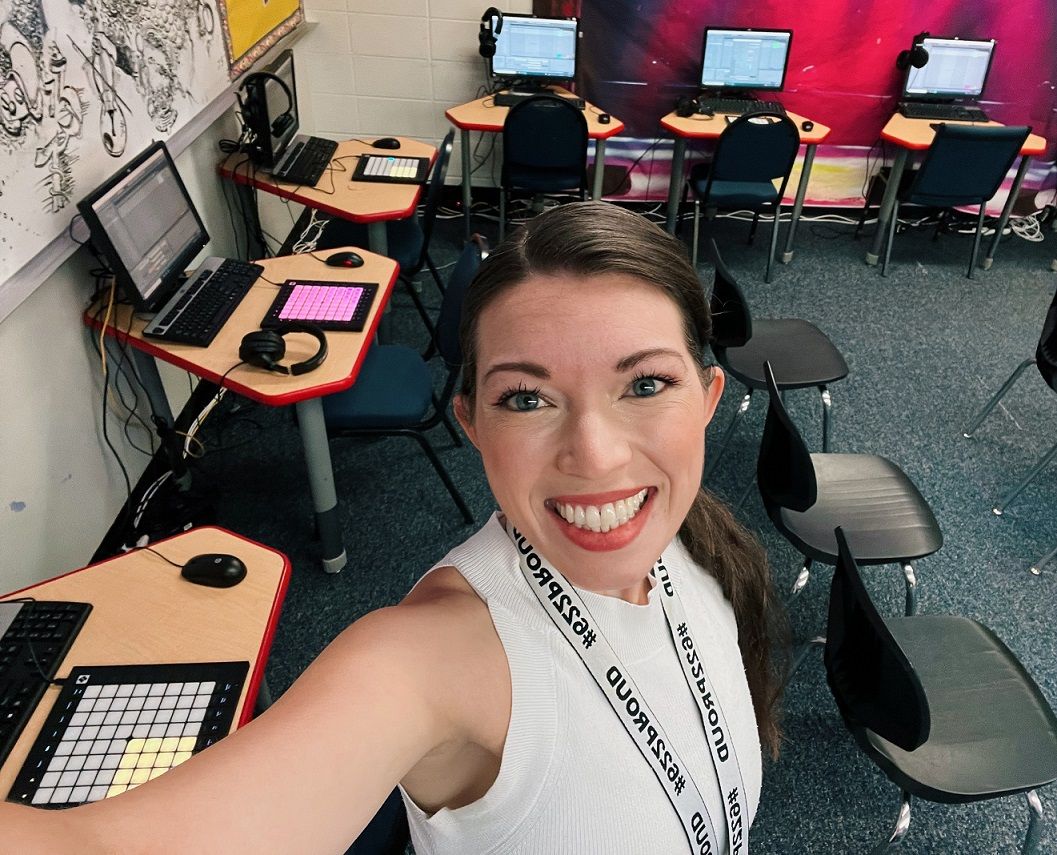

Teaching music, for Burdette, is not just a job. It’s her passion. It’s her calling.

Teaching music, for Burdette, is not just a job. It’s her passion. It’s her calling.

5:45 a.m.

5:45 a.m. 6:30 a.m.

6:30 a.m. 8:30 a.m.

8:30 a.m. Noon

Noon 4 p.m.

4 p.m.

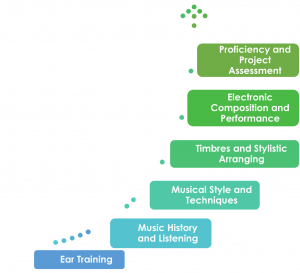

Wigglesworth says that taking all these classes together was making the students not just better performers and musicians, but also better overall learners. Though these students have now graduated, their legacy includes their inspiration for the Performing Arts Academy. “These alumni, they were hungry, they wanted this,” Wigglesworth says. “They started to paint a picture of what could be a reality — and that was the academy.”

Wigglesworth says that taking all these classes together was making the students not just better performers and musicians, but also better overall learners. Though these students have now graduated, their legacy includes their inspiration for the Performing Arts Academy. “These alumni, they were hungry, they wanted this,” Wigglesworth says. “They started to paint a picture of what could be a reality — and that was the academy.” Students involved in the Performing Arts Academy must fit all their private lessons and extra performances into their existing school schedules, which include all traditional school requirements. “Their schedules are pretty jam-packed,” Wigglesworth says.

Students involved in the Performing Arts Academy must fit all their private lessons and extra performances into their existing school schedules, which include all traditional school requirements. “Their schedules are pretty jam-packed,” Wigglesworth says. Because West Covina is located in Southern California, faculty have developed working relationships with professionals from

Because West Covina is located in Southern California, faculty have developed working relationships with professionals from

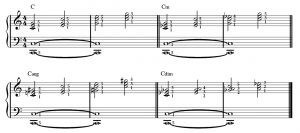

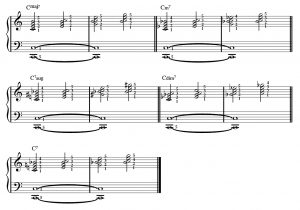

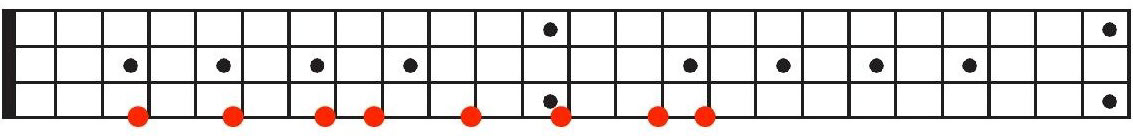

You easily can play complex chords on them. Many chords require just one or two fingers, which allows students to play their favorite pop and Disney songs without the insane stretches that might be required on the guitar (something that is great for kindergartners and students with small hands). Because of the ukulele’s unique tuning and its smaller fretboard, suspended and 7ths chords are easier to learn.

You easily can play complex chords on them. Many chords require just one or two fingers, which allows students to play their favorite pop and Disney songs without the insane stretches that might be required on the guitar (something that is great for kindergartners and students with small hands). Because of the ukulele’s unique tuning and its smaller fretboard, suspended and 7ths chords are easier to learn. Don’t start teaching with the instruments already in students’ hands. Instead, create a presentation on how to properly hold and use ukuleles, including examples of what not to do. Tuning, maintenance and how to put the instrument away should all be addressed a day before the instruments are put into their hands.

Don’t start teaching with the instruments already in students’ hands. Instead, create a presentation on how to properly hold and use ukuleles, including examples of what not to do. Tuning, maintenance and how to put the instrument away should all be addressed a day before the instruments are put into their hands. If you don’t already have ukes in your classroom, you’ll need to do a bit of research. Most entry-level ukuleles cost around $50 to $60. Anything less than this are likely not high quality instruments. Entry-level ukuleles are usually made of wood or plastic. Most classroom sets are plastic, although there are a handful of economical wooden ones (such as those by Makala), but instruments made of wood require more care and are more susceptible to damage.

If you don’t already have ukes in your classroom, you’ll need to do a bit of research. Most entry-level ukuleles cost around $50 to $60. Anything less than this are likely not high quality instruments. Entry-level ukuleles are usually made of wood or plastic. Most classroom sets are plastic, although there are a handful of economical wooden ones (such as those by Makala), but instruments made of wood require more care and are more susceptible to damage. I’m supportive of using both ukuleles and

I’m supportive of using both ukuleles and

I enjoy live music, but hearing exceptional groups reduced my confidence. Still, it was important to continue this exposure, not only to continue getting examples of what I wanted, but for my own enjoyment as well.

I enjoy live music, but hearing exceptional groups reduced my confidence. Still, it was important to continue this exposure, not only to continue getting examples of what I wanted, but for my own enjoyment as well. We know when something doesn’t sound like we want it to, but what do we do when we’re in the middle of rehearsal? If something sounds off but you can’t put your finger on it, start separating the parts. Break down complex pieces to understand them better.

We know when something doesn’t sound like we want it to, but what do we do when we’re in the middle of rehearsal? If something sounds off but you can’t put your finger on it, start separating the parts. Break down complex pieces to understand them better. Whether they sound off or not, make a habit of tuning specific notes and chords to ensure uniformity. I started by picking one student to play a note. I then played my instrument and tuned to them. This showed an example of what “in tune” sounded like. Later, we started having kids tune to each other — just a couple each day.

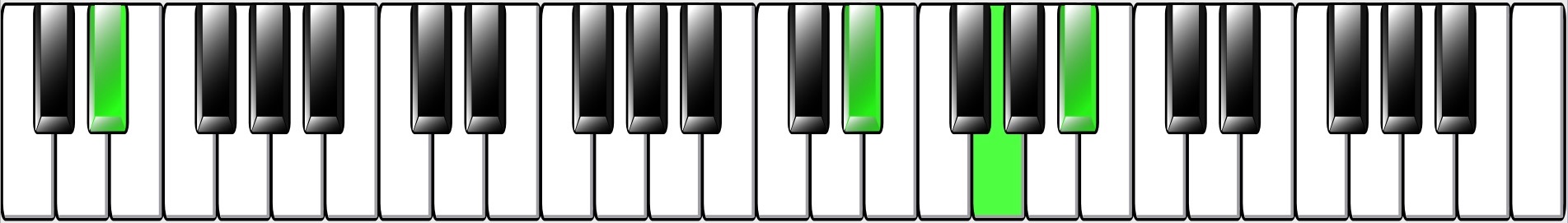

Whether they sound off or not, make a habit of tuning specific notes and chords to ensure uniformity. I started by picking one student to play a note. I then played my instrument and tuned to them. This showed an example of what “in tune” sounded like. Later, we started having kids tune to each other — just a couple each day. Delve deep into the music, studying one line at a time. I’m serious. Take a piece and plunk out every single instrument line on the piano, or grab an instrument and play through. Go through every line and see what your kids are actually playing. Then do it again. Then one more time.

Delve deep into the music, studying one line at a time. I’m serious. Take a piece and plunk out every single instrument line on the piano, or grab an instrument and play through. Go through every line and see what your kids are actually playing. Then do it again. Then one more time.

Directions: Assign an instrument to your students and, with the help of their parent or guardian, ask students to search online to answer a given set of questions. Some of these answers might be hard to find, but they’ll end their journey knowing a few more fun facts. Students can present these facts to the class, or the answers can be used to create an interactive round of

Directions: Assign an instrument to your students and, with the help of their parent or guardian, ask students to search online to answer a given set of questions. Some of these answers might be hard to find, but they’ll end their journey knowing a few more fun facts. Students can present these facts to the class, or the answers can be used to create an interactive round of  Directions: Ask your students to craft a make-shift microphone, turn down the lights and throw their own karaoke night in the living room with their friends or family. Whether they use Disney singalongs or

Directions: Ask your students to craft a make-shift microphone, turn down the lights and throw their own karaoke night in the living room with their friends or family. Whether they use Disney singalongs or

Recently, I took my students at

Recently, I took my students at  Share Circle

Share Circle

My favorite students are those who are always enthusiastic or engaged during my rehearsals, even when I knew they didn’t want to be there. The kids who made it easy for me to teach when maybe I didn’t want to be there. Kids tend to see their teachers as superhuman and expect us to always be at our best. On my most challenging days, the few kids who went out of their way to smile and say good morning or check in with me, made all the difference.

My favorite students are those who are always enthusiastic or engaged during my rehearsals, even when I knew they didn’t want to be there. The kids who made it easy for me to teach when maybe I didn’t want to be there. Kids tend to see their teachers as superhuman and expect us to always be at our best. On my most challenging days, the few kids who went out of their way to smile and say good morning or check in with me, made all the difference. I remember how it started in 2021 during the post-COVID re-boot. We were all looking for ways to boost morale and confidence. At a rehearsal early on during spring training, Gino tested the microphone. The kids couldn’t hear it from the field, so they started to scream “What?! What?! What?!” until Gino yelled, “Checking the microphone!” at a volume they could hear. They all cheered and screamed exuberantly.

I remember how it started in 2021 during the post-COVID re-boot. We were all looking for ways to boost morale and confidence. At a rehearsal early on during spring training, Gino tested the microphone. The kids couldn’t hear it from the field, so they started to scream “What?! What?! What?!” until Gino yelled, “Checking the microphone!” at a volume they could hear. They all cheered and screamed exuberantly.

Greet your students daily — at the door or before your rehearsals. Say, “Good morning” or “Good afternoon” while making excellent eye contact, smiling and projecting. If students don’t respond, don’t take it personally. Teenagers mumble. You can inspire them to respond with your energy or teach them to respond.

Greet your students daily — at the door or before your rehearsals. Say, “Good morning” or “Good afternoon” while making excellent eye contact, smiling and projecting. If students don’t respond, don’t take it personally. Teenagers mumble. You can inspire them to respond with your energy or teach them to respond. If a normally cheerful student looks sad or is acting out of sorts, take a second to investigate. “Hey, you normally answer many questions in rehearsal, but you seemed quiet today. Is everything ok?” When students have bad body language in rehearsals, don’t assume it’s a response to you, the rehearsal or even that the student realizes they have bad body language. We can help students learn the power of their body language through coaching and raising awareness.

If a normally cheerful student looks sad or is acting out of sorts, take a second to investigate. “Hey, you normally answer many questions in rehearsal, but you seemed quiet today. Is everything ok?” When students have bad body language in rehearsals, don’t assume it’s a response to you, the rehearsal or even that the student realizes they have bad body language. We can help students learn the power of their body language through coaching and raising awareness.

She made a youthful executive decision: “I’m not only going to become a music educator, but I’m also going to work in schools that have predominantly Black and brown programs.”

She made a youthful executive decision: “I’m not only going to become a music educator, but I’m also going to work in schools that have predominantly Black and brown programs.” Soon after her post traveled wide, Fripp was speaking on podcasts and headlining conferences. Additional social media posts followed, and she signed one as “A Passionate Black Educator.” Since then, the name stuck.

Soon after her post traveled wide, Fripp was speaking on podcasts and headlining conferences. Additional social media posts followed, and she signed one as “A Passionate Black Educator.” Since then, the name stuck.

She offers some tips to fellow music teachers. For people of color, she says, be proactive and speak up about your needs by getting involved with professional organizations and attending board meetings. “Don’t be afraid to use your voice, because you’re giving voice to the voiceless.” Fripp says.

She offers some tips to fellow music teachers. For people of color, she says, be proactive and speak up about your needs by getting involved with professional organizations and attending board meetings. “Don’t be afraid to use your voice, because you’re giving voice to the voiceless.” Fripp says.

I highly value my music department teammates, but I had to learn how to be an effective member of the team. I had to open my mind to the concept that the success of my colleagues’ programs was just as important as mine. I came to recognize that many stakeholders view the department holistically and the success of any aspect of our music program was a reflection of our team. I learned how much we had to follow the motto of the Three Musketeers: “One for all and all for one.” Most notably, I realized that like most things in life, what we put into the team is what we will get out of it.

I highly value my music department teammates, but I had to learn how to be an effective member of the team. I had to open my mind to the concept that the success of my colleagues’ programs was just as important as mine. I came to recognize that many stakeholders view the department holistically and the success of any aspect of our music program was a reflection of our team. I learned how much we had to follow the motto of the Three Musketeers: “One for all and all for one.” Most notably, I realized that like most things in life, what we put into the team is what we will get out of it. Your presence alone at a concert sends a clear message to your colleagues that you support them, their students and music education as a whole regardless of which ensemble or grade level is performing. Although showing up is meaningful, a great teammate takes it to the next level by assisting their colleagues during those stressful performances.

Your presence alone at a concert sends a clear message to your colleagues that you support them, their students and music education as a whole regardless of which ensemble or grade level is performing. Although showing up is meaningful, a great teammate takes it to the next level by assisting their colleagues during those stressful performances. Over the past several years, one of the greatest intrinsic benefits of attending performances throughout the district is connecting and advocating with administrators! Take the opportunity to highlight for a principal, superintendent or school board member some of the excellent music learning occurring throughout your district. Mentioning the growth of an ensemble or program is much more impactful to an administrator when the group is sitting on stage with big smiles.

Over the past several years, one of the greatest intrinsic benefits of attending performances throughout the district is connecting and advocating with administrators! Take the opportunity to highlight for a principal, superintendent or school board member some of the excellent music learning occurring throughout your district. Mentioning the growth of an ensemble or program is much more impactful to an administrator when the group is sitting on stage with big smiles.

Offering collaboration as part of being a team player is cliche. In fact, suggesting collaboration alone doesn’t offer much value because all educators must collaborate throughout the day to do their jobs. What I’m suggesting is that great teammates collaborate creatively beyond the routine collective tasks and events we do as colleagues.

Offering collaboration as part of being a team player is cliche. In fact, suggesting collaboration alone doesn’t offer much value because all educators must collaborate throughout the day to do their jobs. What I’m suggesting is that great teammates collaborate creatively beyond the routine collective tasks and events we do as colleagues. The relationships you have with your colleagues matter! Everyone you work with doesn’t need to be a personal friend, but great team players work toward building healthy relationships with their peers. One of the best ways to do this is to gather with your colleagues outside of school. My department meets at least bi-yearly to share in fellowship as a districtwide music educator community.

The relationships you have with your colleagues matter! Everyone you work with doesn’t need to be a personal friend, but great team players work toward building healthy relationships with their peers. One of the best ways to do this is to gather with your colleagues outside of school. My department meets at least bi-yearly to share in fellowship as a districtwide music educator community.

Embarrassingly, I didn’t learn about commissions until I went to college and met composition majors. People asked these composers to write music for them. What? That can happen?! As I became friends with some composers, I started to think about commissioning. Imagine being able to help my friends do what they love by doing what I love.

Embarrassingly, I didn’t learn about commissions until I went to college and met composition majors. People asked these composers to write music for them. What? That can happen?! As I became friends with some composers, I started to think about commissioning. Imagine being able to help my friends do what they love by doing what I love. I have heard a lot of music teachers say, “I only program good music.” However, we all know what that means: They only program the status quo because it is too much work to find something else. If this continues to happen, then music as an art form would never advance because people are afraid to challenge what we already know.

I have heard a lot of music teachers say, “I only program good music.” However, we all know what that means: They only program the status quo because it is too much work to find something else. If this continues to happen, then music as an art form would never advance because people are afraid to challenge what we already know. The beauty of a commission is that it is created for you and your group. It is like that new suit that took the tailor an hour to fit just for you, and when you get the finished product, it fits perfectly — and, boy, do you look good! With a commissioned piece, you can even share it with your colleagues who might have similar instrumentation.

The beauty of a commission is that it is created for you and your group. It is like that new suit that took the tailor an hour to fit just for you, and when you get the finished product, it fits perfectly — and, boy, do you look good! With a commissioned piece, you can even share it with your colleagues who might have similar instrumentation. We are all artists. We know how difficult it can be to make a living by following your passion. Music is an undervalued and underappreciated profession. When you purchase music from a large music distributor, the composer probably is not making that much money from that purchase. I don’t think this is breaking news to anyone.

We are all artists. We know how difficult it can be to make a living by following your passion. Music is an undervalued and underappreciated profession. When you purchase music from a large music distributor, the composer probably is not making that much money from that purchase. I don’t think this is breaking news to anyone. I have a few different processes for finding the right composer. My first commission was with a composer named

I have a few different processes for finding the right composer. My first commission was with a composer named

Tran, who recently left his job to begin a doctoral program in choral conducting at the

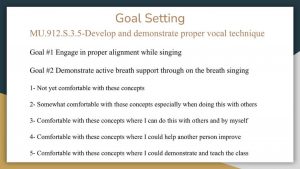

Tran, who recently left his job to begin a doctoral program in choral conducting at the  “I always like to think of it as if you’re going on a trip: You want to put the address into your GPS, so you know where you’re going,” Tran says.

“I always like to think of it as if you’re going on a trip: You want to put the address into your GPS, so you know where you’re going,” Tran says. “Person” and “Process” feedback are two types of responses that affect mindset. Person feedback says: “You’re a great musician.” which praises the ability. Process feedback, by contrast, acknowledges effort: “You did really well on the solo during the concert because you were practicing that.”

“Person” and “Process” feedback are two types of responses that affect mindset. Person feedback says: “You’re a great musician.” which praises the ability. Process feedback, by contrast, acknowledges effort: “You did really well on the solo during the concert because you were practicing that.” Students should review what they have accomplished and the feedback they have received to assess their performance. When Tran does one-on-one check-ins with students, the rest of the class engages in self-reflection.

Students should review what they have accomplished and the feedback they have received to assess their performance. When Tran does one-on-one check-ins with students, the rest of the class engages in self-reflection.

The Tough Teacher: This is the teacher who kids dread seeing, but the one they think about when they’re adults. These teachers are like Batman — the hero that they deserved but not the one they thought they needed at the time. As students, we resist these teachers because they take us out of our educational comfort zone. Then one night when we’re in our 20s, 30s, 40s or older, we wake up and think, “They were right.”

The Tough Teacher: This is the teacher who kids dread seeing, but the one they think about when they’re adults. These teachers are like Batman — the hero that they deserved but not the one they thought they needed at the time. As students, we resist these teachers because they take us out of our educational comfort zone. Then one night when we’re in our 20s, 30s, 40s or older, we wake up and think, “They were right.” The Sage or Mentor: You know these teachers — the ones who drop in with a one liner that you’ll never forget. Sages are similar to the tough teacher, but their timing is impeccable. They have an air of mystery — you don’t interact with them a lot, but when you do, you know something impactful is about to happen. Some of the most profound advice and teachings I have received were from people I rarely saw.

The Sage or Mentor: You know these teachers — the ones who drop in with a one liner that you’ll never forget. Sages are similar to the tough teacher, but their timing is impeccable. They have an air of mystery — you don’t interact with them a lot, but when you do, you know something impactful is about to happen. Some of the most profound advice and teachings I have received were from people I rarely saw. In recent years, we’ve had a much-needed push toward being kinder — this is great! However, I’ve noticed that some people begin confuse kindness with being unable to deliver direct feedback when needed. As teachers, we can be just as concerned with being fair and insistent as we are with being kind or nice.

In recent years, we’ve had a much-needed push toward being kinder — this is great! However, I’ve noticed that some people begin confuse kindness with being unable to deliver direct feedback when needed. As teachers, we can be just as concerned with being fair and insistent as we are with being kind or nice. The first year I wrote these notes, I had 40 students in the band. The next year, I had 75, and eventually, I had 120. At this point, I was looking forward to not writing these notes anymore. Two days before our first concert, a freshman band member came to me after rehearsal and said, “Mr. Stinson, I can’t wait to see what you write on my concert program! We kept hearing in junior high that everyone gets one!”

The first year I wrote these notes, I had 40 students in the band. The next year, I had 75, and eventually, I had 120. At this point, I was looking forward to not writing these notes anymore. Two days before our first concert, a freshman band member came to me after rehearsal and said, “Mr. Stinson, I can’t wait to see what you write on my concert program! We kept hearing in junior high that everyone gets one!” Balance

Balance Other examples may have a more layered effect. If we don’t care about poor behavior, then we may be sending a message that we don’t care about the kids who are contributing positively. These students may then wonder what’s the point in contributing to a system that may end up having diminishing returns.

Other examples may have a more layered effect. If we don’t care about poor behavior, then we may be sending a message that we don’t care about the kids who are contributing positively. These students may then wonder what’s the point in contributing to a system that may end up having diminishing returns.

Sims first encountered GRR as a pedagogy during his college years, and then began developing his approach more with each teaching job. “I was a super nerd in college, so I read everything I could get my hands on,” he says with a laugh.

Sims first encountered GRR as a pedagogy during his college years, and then began developing his approach more with each teaching job. “I was a super nerd in college, so I read everything I could get my hands on,” he says with a laugh. Once students have mastered analyzing their own performances during warmup, Sims starts letting them guide exercises in method books. Here, transfer of knowledge is key. Students learn to apply their critiques from the warmup to their analysis of the actual rehearsal. “Sometimes, kids will get stumped,” he says. “I can ask leading questions like, ‘During the warmup, you said tuning was an issue. What did we do during the warmup?’ And then [they fix it] almost immediately.”

Once students have mastered analyzing their own performances during warmup, Sims starts letting them guide exercises in method books. Here, transfer of knowledge is key. Students learn to apply their critiques from the warmup to their analysis of the actual rehearsal. “Sometimes, kids will get stumped,” he says. “I can ask leading questions like, ‘During the warmup, you said tuning was an issue. What did we do during the warmup?’ And then [they fix it] almost immediately.” Middle school students are often in a developmental stage that blends high energy with social uncertainty. To keep his classroom running efficiently, Sims sets high expectations for his students’ maturity level. “Depending on the kid or the age level, sometimes it takes a little while to teach the maturity behind making intelligent musical comments,” Sims says. “Some students have a tough time either giving constructive criticism or receiving it.”

Middle school students are often in a developmental stage that blends high energy with social uncertainty. To keep his classroom running efficiently, Sims sets high expectations for his students’ maturity level. “Depending on the kid or the age level, sometimes it takes a little while to teach the maturity behind making intelligent musical comments,” Sims says. “Some students have a tough time either giving constructive criticism or receiving it.” By making an intentional effort to engage students with one another, Sims breaks down typical preteen cliques, helps students come out of their shells and builds the band into a cohesive unit. “What’s awesome is, whenever kids come into the band room for the first time, they’re all in these little friend groups,” Sims says. “As the year progresses, you’ll see them with a different group.”

By making an intentional effort to engage students with one another, Sims breaks down typical preteen cliques, helps students come out of their shells and builds the band into a cohesive unit. “What’s awesome is, whenever kids come into the band room for the first time, they’re all in these little friend groups,” Sims says. “As the year progresses, you’ll see them with a different group.”

According to Griffin, there has been a noticeable lapse in the preservation of Cajun and Creole culture from her grandparents’ generation to her own. “I feel like our culture has just been slowly taken away from us, and we’re paying the price,” she says.

According to Griffin, there has been a noticeable lapse in the preservation of Cajun and Creole culture from her grandparents’ generation to her own. “I feel like our culture has just been slowly taken away from us, and we’re paying the price,” she says. Griffin earned a bachelor’s degree in music education at the

Griffin earned a bachelor’s degree in music education at the  Two summers ago, Griffin along with her husband, Gregg, and another district music educator, started

Two summers ago, Griffin along with her husband, Gregg, and another district music educator, started

“Louisiana’s music culture is so rich with jazz and all these things that come from our state,” she says. “But in our school programs, our kids play mostly western, classical and noncultural music.”

“Louisiana’s music culture is so rich with jazz and all these things that come from our state,” she says. “But in our school programs, our kids play mostly western, classical and noncultural music.”

The good news is that there are many ways to create music for video games, so you can find what works best for you.

The good news is that there are many ways to create music for video games, so you can find what works best for you. Many short, repeated themes must be written. Video game composers specialize in incidental music, which is music written for something that isn’t music-centric (such as a symphony you’d buy tickets to see).

Many short, repeated themes must be written. Video game composers specialize in incidental music, which is music written for something that isn’t music-centric (such as a symphony you’d buy tickets to see).

1. Start on the Musicality Immediately

1. Start on the Musicality Immediately

7. Let Them Play

7. Let Them Play My experience as a conductor comes in handy because I’ve learned to communicate with gestures instead of words. During a concert you’re going to use gestures to get students to respond. Why not show them during rehearsal?

My experience as a conductor comes in handy because I’ve learned to communicate with gestures instead of words. During a concert you’re going to use gestures to get students to respond. Why not show them during rehearsal?

Just make a short list of the things you teach in your classroom: dependability, responsibility, respect, encouragement, leadership, teamwork, how to grow from disappointment, how to win, how to lose, punctuality, dedication. The list goes on and on.

Just make a short list of the things you teach in your classroom: dependability, responsibility, respect, encouragement, leadership, teamwork, how to grow from disappointment, how to win, how to lose, punctuality, dedication. The list goes on and on. With that in mind, I went to the head of our CTE department for the school district and had an open conversation about my desire to champion students who are excelling in multiple programs. My main talking point focused on my senior drum major who is an amazing leader, flute player, powerlifter and advanced welder! Wow! Let’s show off her amazing talents AND how incredible our school district, administrators and her parents are for helping her along this very diverse pathway. These are the stories we need to tell (and sell!).

With that in mind, I went to the head of our CTE department for the school district and had an open conversation about my desire to champion students who are excelling in multiple programs. My main talking point focused on my senior drum major who is an amazing leader, flute player, powerlifter and advanced welder! Wow! Let’s show off her amazing talents AND how incredible our school district, administrators and her parents are for helping her along this very diverse pathway. These are the stories we need to tell (and sell!).

Letter names scribbled under every note.

Letter names scribbled under every note. The basic principle of sound before sight is that aural comprehension precedes theory or grammar, similar to how humans learn language. Keep in mind that aural comprehension is not the same as rote memorization. The two can be distinguished by the following analogy: Imagine you had to memorize a speech in a language that you don’t comprehend. You might be able to say the sounds mostly correctly, but you don’t understand what you’re saying, nor could you use the words you’ve memorized to improvise new sentences. In music, a student might memorize a piece but make a pitch error and not notice. They may be unable to identify a tonal center or whether the piece is in major or minor. And perhaps they are unable to take an excerpt and transpose or improvise on it.

The basic principle of sound before sight is that aural comprehension precedes theory or grammar, similar to how humans learn language. Keep in mind that aural comprehension is not the same as rote memorization. The two can be distinguished by the following analogy: Imagine you had to memorize a speech in a language that you don’t comprehend. You might be able to say the sounds mostly correctly, but you don’t understand what you’re saying, nor could you use the words you’ve memorized to improvise new sentences. In music, a student might memorize a piece but make a pitch error and not notice. They may be unable to identify a tonal center or whether the piece is in major or minor. And perhaps they are unable to take an excerpt and transpose or improvise on it. Get ready for a hot take: A lot of sight-reading happening out there isn’t really reading at all. Stay with me. Often, sight-reading looks like giving students a new piece or exercise in their method book. They look at the sheet music but cannot hear what it would sound like in their head. So, they start to decode the first note symbol into the correct fingering, then the next and the next. Then they string it together, maybe with some unnoticed pitch errors. Were they reading?

Get ready for a hot take: A lot of sight-reading happening out there isn’t really reading at all. Stay with me. Often, sight-reading looks like giving students a new piece or exercise in their method book. They look at the sheet music but cannot hear what it would sound like in their head. So, they start to decode the first note symbol into the correct fingering, then the next and the next. Then they string it together, maybe with some unnoticed pitch errors. Were they reading? It has to be clear that notation is representation of a pitch, not of a letter name or a fingering: I postpone referring to notes by letter names for a few months in order to emphasize patterns and tonality. We use solfege or neutral syllables on each pitch. I start beginners on a one- or two-line staff to simplify patterns, emphasize the sound and symbol relationship, and deemphasize the inclination to name notes. Eventually I scaffold up to traditional notation.

It has to be clear that notation is representation of a pitch, not of a letter name or a fingering: I postpone referring to notes by letter names for a few months in order to emphasize patterns and tonality. We use solfege or neutral syllables on each pitch. I start beginners on a one- or two-line staff to simplify patterns, emphasize the sound and symbol relationship, and deemphasize the inclination to name notes. Eventually I scaffold up to traditional notation. So, why does this shift to holistic music literacy matter? What are the stakes? I can’t say how many adults I’ve met who, at some point, got the message that they “just weren’t musical” or “just weren’t talented,” so they quit learning music. Unfortunately, this is still happening today. Stories like these, I believe, are the result of a way of teaching that often fails to impart holistic music literacy. The truth is: Musicality is an inherent human trait, just like language. With the right teaching, the musician in everyone can flourish.

So, why does this shift to holistic music literacy matter? What are the stakes? I can’t say how many adults I’ve met who, at some point, got the message that they “just weren’t musical” or “just weren’t talented,” so they quit learning music. Unfortunately, this is still happening today. Stories like these, I believe, are the result of a way of teaching that often fails to impart holistic music literacy. The truth is: Musicality is an inherent human trait, just like language. With the right teaching, the musician in everyone can flourish.

The goal of Notice-Shift-Rewire is to help master executive attention. What’s executive attention? It’s the complex way our brain sorts out all the incoming stimuli, blocking out what’s not important and focusing on what needs doing. Picture yourself having dinner with a friend: You are focused on the great story they are telling you, not on the random guy in the blue shirt at the next table over or the sound of your fork on your plate. When executive attention is poor, according to Klemp and Langshur, too many stimuli are competing, which makes us feel distracted, unfocused and stressed. (Sound familiar?) Add in today’s fragmented environment — awash with distracting social media, incoming texts and multiple screens — and our poor brains are swamped.

The goal of Notice-Shift-Rewire is to help master executive attention. What’s executive attention? It’s the complex way our brain sorts out all the incoming stimuli, blocking out what’s not important and focusing on what needs doing. Picture yourself having dinner with a friend: You are focused on the great story they are telling you, not on the random guy in the blue shirt at the next table over or the sound of your fork on your plate. When executive attention is poor, according to Klemp and Langshur, too many stimuli are competing, which makes us feel distracted, unfocused and stressed. (Sound familiar?) Add in today’s fragmented environment — awash with distracting social media, incoming texts and multiple screens — and our poor brains are swamped. The first part of the practice is to notice, or observe, what’s happening in your mind, using a neutral standpoint. Let’s say you had a really hard day teaching. You feel depleted and discouraged. Your brain starts whirring with negative, unhelpful thoughts — for example, “I should be better at this by now” or “I am not cut out for teaching.” But here’s the thing: Human brains are wired to glom onto more negative thoughts and experiences instead of positive thoughts and experiences. Giving negative thoughts more energy is what scientists call the

The first part of the practice is to notice, or observe, what’s happening in your mind, using a neutral standpoint. Let’s say you had a really hard day teaching. You feel depleted and discouraged. Your brain starts whirring with negative, unhelpful thoughts — for example, “I should be better at this by now” or “I am not cut out for teaching.” But here’s the thing: Human brains are wired to glom onto more negative thoughts and experiences instead of positive thoughts and experiences. Giving negative thoughts more energy is what scientists call the  Rewire

Rewire

Choose your cart carefully because it is your classroom. Helpful features to have on a music cart include:

Choose your cart carefully because it is your classroom. Helpful features to have on a music cart include: Hand Clapping and Cups: The smaller the instruments, the easier it’s going to be for you. However, this doesn’t mean that you can’t make great music. Prioritize small hand percussion instruments like scrapers, shakers and handbells. Don’t forget that our bodies can be instruments, too.

Hand Clapping and Cups: The smaller the instruments, the easier it’s going to be for you. However, this doesn’t mean that you can’t make great music. Prioritize small hand percussion instruments like scrapers, shakers and handbells. Don’t forget that our bodies can be instruments, too. Small Manipulatives and Other Helpful Items: Keep small items in your cart like scarves (for choreography), balls, hacky sacks, rubber dots, etc. that are portable, engaging and inspire movement. Other helpful things to keep on hand include mini whiteboards, golf pencils, scrap paper and blank staff paper.

Small Manipulatives and Other Helpful Items: Keep small items in your cart like scarves (for choreography), balls, hacky sacks, rubber dots, etc. that are portable, engaging and inspire movement. Other helpful things to keep on hand include mini whiteboards, golf pencils, scrap paper and blank staff paper. Teacher Tip: Take Up Space — Even if you’re always teaching in someone else’s space, you must think of it as your room until the bell rings. It’s also a valid move to ask the other teacher to leave their desk so you can take over, even if it’s uncomfortable at first.

Teacher Tip: Take Up Space — Even if you’re always teaching in someone else’s space, you must think of it as your room until the bell rings. It’s also a valid move to ask the other teacher to leave their desk so you can take over, even if it’s uncomfortable at first.

What’s the Difference Between Matte and Glossy?

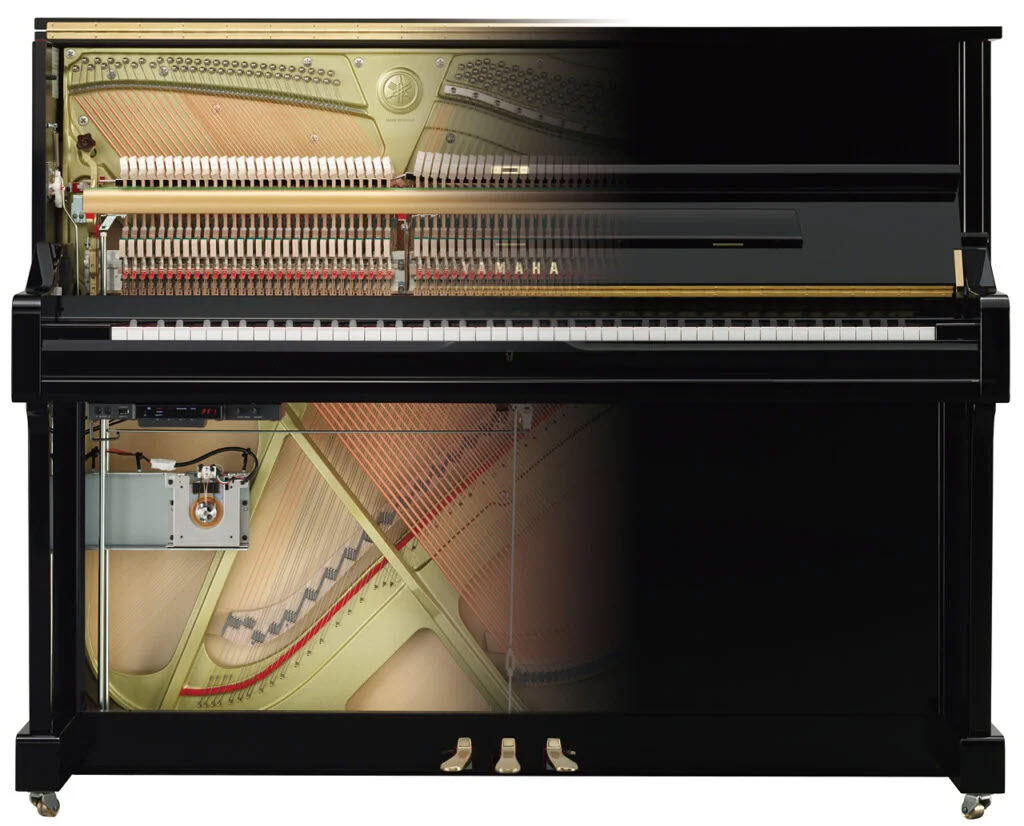

What’s the Difference Between Matte and Glossy? Vibraphone bars are graduated in size and length the same way they are on a marimba and xylophone. This means that the bars are at their largest in width and length at the bottom and gradually get smaller as the pitch rises. The same principle applies to a grand piano. When you look inside a piano, the strings attached to the higher notes are very short and thin, while lower pitches have thicker and longer strings.

Vibraphone bars are graduated in size and length the same way they are on a marimba and xylophone. This means that the bars are at their largest in width and length at the bottom and gradually get smaller as the pitch rises. The same principle applies to a grand piano. When you look inside a piano, the strings attached to the higher notes are very short and thin, while lower pitches have thicker and longer strings. The vibraphone bars are tuned to A=442hz (like most other pitched percussion), however, if you are playing the vibraphone with a grand piano tuned to A=440hz, you might notice some tuning discrepancies. The vibraphone is technically 8 cents sharp compared to the piano and the rest of the ensemble. For this reason, companies will offer vibraphone bars tuned to A=440hz. This is only necessary when playing in smaller ensembles with a grand piano or other fixed pitched instruments, however, the difference isn’t noticeable in most scenarios.

The vibraphone bars are tuned to A=442hz (like most other pitched percussion), however, if you are playing the vibraphone with a grand piano tuned to A=440hz, you might notice some tuning discrepancies. The vibraphone is technically 8 cents sharp compared to the piano and the rest of the ensemble. For this reason, companies will offer vibraphone bars tuned to A=440hz. This is only necessary when playing in smaller ensembles with a grand piano or other fixed pitched instruments, however, the difference isn’t noticeable in most scenarios.

Early priorities included infrastructure, such as great trucks, great buses, great equipment. The next priorities included uniform and equipment sponsorships. Once these pieces were in place, the board secured the best teaching staff and administrators they could find. Then, they trusted those instructors and teachers to do their jobs and provided them with the resources needed to be successful. There was, of course, give and take, such as metrics, goals and incentives. The board provided fantastic oversight in the early days, but as the corps’ leadership became more solid, the board maintained its focus on fundraising and community involvement.

Early priorities included infrastructure, such as great trucks, great buses, great equipment. The next priorities included uniform and equipment sponsorships. Once these pieces were in place, the board secured the best teaching staff and administrators they could find. Then, they trusted those instructors and teachers to do their jobs and provided them with the resources needed to be successful. There was, of course, give and take, such as metrics, goals and incentives. The board provided fantastic oversight in the early days, but as the corps’ leadership became more solid, the board maintained its focus on fundraising and community involvement. On top of being a dedicated band parent, Don was a leading spinal surgeon in South Carolina, and he was positioned to rally the community to support the organization. He envisioned a support system for the Wando Band that could engage alums and other stakeholders to raise monies for the campus and the middle school programs. He was wholly committed to keeping band costs down and filling in the gaps in funding at the district level to enable Wando to remain competitive nationally. He also extended support to the middle school feeders that required additional funding for equipment or travel.

On top of being a dedicated band parent, Don was a leading spinal surgeon in South Carolina, and he was positioned to rally the community to support the organization. He envisioned a support system for the Wando Band that could engage alums and other stakeholders to raise monies for the campus and the middle school programs. He was wholly committed to keeping band costs down and filling in the gaps in funding at the district level to enable Wando to remain competitive nationally. He also extended support to the middle school feeders that required additional funding for equipment or travel.

We often think of recruitment as a one-night-only event. You show up, the kids see and/or try the instruments, and then they sign up. That’s it.

We often think of recruitment as a one-night-only event. You show up, the kids see and/or try the instruments, and then they sign up. That’s it. That first general music class visit in the winter is short! I demo all four string instruments and introduce our programs in about 15 minutes. I am saccharine sweet and bubbly. Why? Because kids have limited attention spans, and the worst thing I can do is drone on about class rules and logistics. No need to talk about rental fees or playing tests. They will come later. It’s easy to forget that a big reason kids join your program is because of you! Be energetic, welcoming and fun. They’ll leave thinking, “Wow, I want to be in that teacher’s class!”

That first general music class visit in the winter is short! I demo all four string instruments and introduce our programs in about 15 minutes. I am saccharine sweet and bubbly. Why? Because kids have limited attention spans, and the worst thing I can do is drone on about class rules and logistics. No need to talk about rental fees or playing tests. They will come later. It’s easy to forget that a big reason kids join your program is because of you! Be energetic, welcoming and fun. They’ll leave thinking, “Wow, I want to be in that teacher’s class!” One year, our band directors were lamenting about their low numbers. It was noted that we had opt-in testing. Students had to turn in a form to try the instruments. That is a barrier to participation, and we want as few barriers as possible. So, we worked with our administration to switch to opt-out testing. Students are brought down to the try-on room as a whole class. Every student tries at least one instrument, unless they have a note from their parent/guardian asking them not to (which is incredibly rare). Upon making this change, our numbers skyrocketed.

One year, our band directors were lamenting about their low numbers. It was noted that we had opt-in testing. Students had to turn in a form to try the instruments. That is a barrier to participation, and we want as few barriers as possible. So, we worked with our administration to switch to opt-out testing. Students are brought down to the try-on room as a whole class. Every student tries at least one instrument, unless they have a note from their parent/guardian asking them not to (which is incredibly rare). Upon making this change, our numbers skyrocketed. Because every student tries instruments, following up is a simple process. A letter goes out to all 5th-grade families, reminding them of the opportunity to join a music ensemble. Our secretaries help with the logistics. We skip the students who have already signed up and send a letter to everyone else.

Because every student tries instruments, following up is a simple process. A letter goes out to all 5th-grade families, reminding them of the opportunity to join a music ensemble. Our secretaries help with the logistics. We skip the students who have already signed up and send a letter to everyone else. It’s Worth it!

It’s Worth it!

According to Sepulvado, the Teaching Lab’s focus on underserved forms of music education stems from a desire to make music more accessible to a wider variety of students. “One of the most important discussions happening in education is about equity and how to meet students where they are,” he says. “I’m a big believer in the importance of classical music and jazz, but I do think there’s tremendous power and value in having a class where students are playing music that they listen to and love.”

According to Sepulvado, the Teaching Lab’s focus on underserved forms of music education stems from a desire to make music more accessible to a wider variety of students. “One of the most important discussions happening in education is about equity and how to meet students where they are,” he says. “I’m a big believer in the importance of classical music and jazz, but I do think there’s tremendous power and value in having a class where students are playing music that they listen to and love.”

Those of us who teach elementary music are often skilled at making handmade crafts, so why not put our talent to use? From sheet music plaques to music-themed throw pillows and jewelry, the ideas are endless. Plus, making handmade items for other music lovers is extremely gratifying.

Those of us who teach elementary music are often skilled at making handmade crafts, so why not put our talent to use? From sheet music plaques to music-themed throw pillows and jewelry, the ideas are endless. Plus, making handmade items for other music lovers is extremely gratifying. Church Musician

Church Musician

Other Side Hustles

Other Side Hustles

Understanding various leadership models and theories can help a teacher-leader be better equipped to explore leadership opportunities within their schools as well as serve the greater community. Considering the attributes of an ideal leader, characteristics of traditional managerial theories are often superseded by human goodness virtues such as hope and trust.

Understanding various leadership models and theories can help a teacher-leader be better equipped to explore leadership opportunities within their schools as well as serve the greater community. Considering the attributes of an ideal leader, characteristics of traditional managerial theories are often superseded by human goodness virtues such as hope and trust.

Successful teacher-leaders explore strategies and model continuous learning, reflective practices and promote higher levels of collaboration among colleagues. They work to consistently align instructional practices with school goals, mission and vision. They accomplish this by circling back to hope, which is the necessary access point that helps us find pathways to achieve goals and navigate around obstacles.

Successful teacher-leaders explore strategies and model continuous learning, reflective practices and promote higher levels of collaboration among colleagues. They work to consistently align instructional practices with school goals, mission and vision. They accomplish this by circling back to hope, which is the necessary access point that helps us find pathways to achieve goals and navigate around obstacles. There is a great responsibility that comes with leadership including the continual pursuit of enlightenment, seeing the bigger picture and rising above the hard and long days because your eyes are on the greater prize. I encourage you to continue expanding your knowledge base and forging collegial relationships to become the most effective teacher-leader and educator possible.

There is a great responsibility that comes with leadership including the continual pursuit of enlightenment, seeing the bigger picture and rising above the hard and long days because your eyes are on the greater prize. I encourage you to continue expanding your knowledge base and forging collegial relationships to become the most effective teacher-leader and educator possible.

The

The  This instrument is considered the professional standard. Almost all modern marimba compositions are written for this instrument and nearly every piece that has been written for the marimba can be played on the 5-octave. It offers the widest range of notes as well as the warmest tone quality in the bass register.

This instrument is considered the professional standard. Almost all modern marimba compositions are written for this instrument and nearly every piece that has been written for the marimba can be played on the 5-octave. It offers the widest range of notes as well as the warmest tone quality in the bass register. Rosewood feels much different to play because of the way it gives when you strike the bars compared to its synthetic counterpart. In the last decade, a great alternative to rosewood called padauk wood has become popular. While this wood doesn’t quite sound as full as rosewood, it is a great substitute for schools and musicians who can’t afford a rosewood instrument but still want a marimba that has the same feel as that of professional rosewood marimbas.

Rosewood feels much different to play because of the way it gives when you strike the bars compared to its synthetic counterpart. In the last decade, a great alternative to rosewood called padauk wood has become popular. While this wood doesn’t quite sound as full as rosewood, it is a great substitute for schools and musicians who can’t afford a rosewood instrument but still want a marimba that has the same feel as that of professional rosewood marimbas.

1. Tunebat

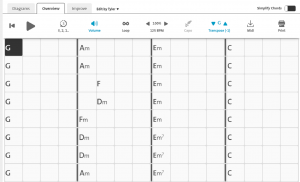

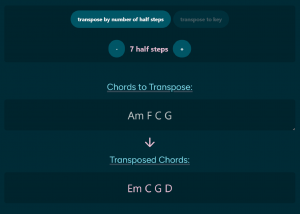

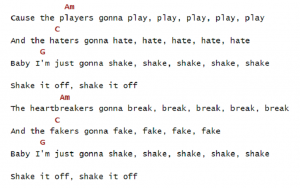

1. Tunebat 2. Chordify

2. Chordify

5. GetSongKey

5. GetSongKey In which genre should we paint our new arrangement? If you have the luxury of choice, head over to

In which genre should we paint our new arrangement? If you have the luxury of choice, head over to

The first step in developing this certificate was drafting and justifying my home department’s needs and resources — a multiyear process that highlights the tremendous inertia that resists change in music departments. My biggest challenge during this phase was getting everyone to vote on the proposal rather than just discuss it into oblivion. For two years, I missed our curricular proposal deadline before getting it done in time. In order to get it to a vote, I not only had a complete draft of the proposal, but I also had commitments for resources from within and outside of the department. A crucial piece of support was from the School of the Arts and the dean’s office that oversee our department. I was promised resources for this specific project, resources that my department spent time discussing how to reorient toward other projects.

The first step in developing this certificate was drafting and justifying my home department’s needs and resources — a multiyear process that highlights the tremendous inertia that resists change in music departments. My biggest challenge during this phase was getting everyone to vote on the proposal rather than just discuss it into oblivion. For two years, I missed our curricular proposal deadline before getting it done in time. In order to get it to a vote, I not only had a complete draft of the proposal, but I also had commitments for resources from within and outside of the department. A crucial piece of support was from the School of the Arts and the dean’s office that oversee our department. I was promised resources for this specific project, resources that my department spent time discussing how to reorient toward other projects. The second way that we have supported Boise State’s comprehensive music education mission is through our community partnership with

The second way that we have supported Boise State’s comprehensive music education mission is through our community partnership with  Throughout the next semester, I gathered technical needs from each ensemble, scheduled photo shoots and wrote marketing pieces. The week of the festival, we loaded the gear on a flatbed truck that we borrowed from the theater department and went down to the Egyptian Theater for the show.

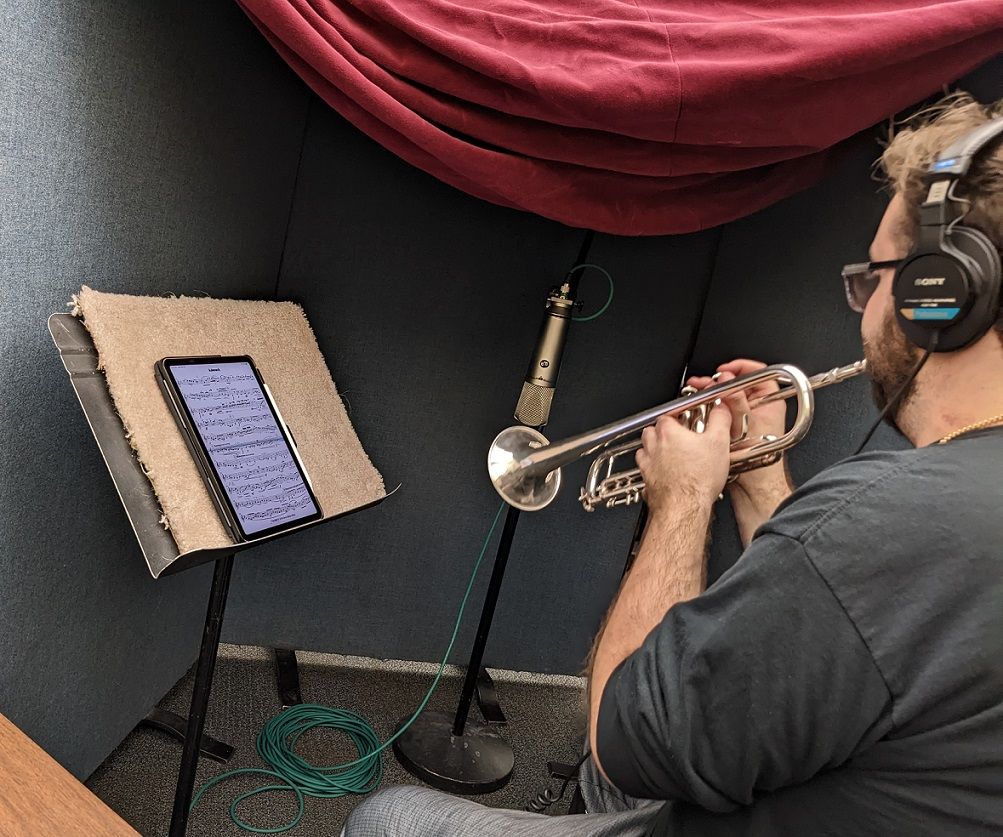

Throughout the next semester, I gathered technical needs from each ensemble, scheduled photo shoots and wrote marketing pieces. The week of the festival, we loaded the gear on a flatbed truck that we borrowed from the theater department and went down to the Egyptian Theater for the show. The second BA project was for Chris Woods, a trumpet student of mine. I asked him, “What is one thing that you wish you could leave here having done that will help you with your career?” His answer: to record a solo trumpet album. Hardly anyone his age has a solo album, and it is something that could set him apart in his field. Furthermore, recording an album has so much more value than a one-and-done recital that you likely won’t want to use or save for any reason (such is the culture in music performance). I helped Chris plan out his album and repertoire. Then I talked him through what the process would look like if I was the producer/engineer and he was the soloist. He arranged rehearsals, booked spaces, marked up scores and prepared his music. As a producer, I set up the recording sessions and did the mixing and mastering. Throughout the process, I helped Chris understand the vocabulary, expectations and process that an artist would go through when recording a solo album. This was an invaluable experience for him. The first time he is recording a solo album on his own in the professional world won’t be the first time he has gone through the process. This album is set to be released on Spotify and be presented in our undergraduate research showcase this spring.

The second BA project was for Chris Woods, a trumpet student of mine. I asked him, “What is one thing that you wish you could leave here having done that will help you with your career?” His answer: to record a solo trumpet album. Hardly anyone his age has a solo album, and it is something that could set him apart in his field. Furthermore, recording an album has so much more value than a one-and-done recital that you likely won’t want to use or save for any reason (such is the culture in music performance). I helped Chris plan out his album and repertoire. Then I talked him through what the process would look like if I was the producer/engineer and he was the soloist. He arranged rehearsals, booked spaces, marked up scores and prepared his music. As a producer, I set up the recording sessions and did the mixing and mastering. Throughout the process, I helped Chris understand the vocabulary, expectations and process that an artist would go through when recording a solo album. This was an invaluable experience for him. The first time he is recording a solo album on his own in the professional world won’t be the first time he has gone through the process. This album is set to be released on Spotify and be presented in our undergraduate research showcase this spring. I hope that my experiences have served to inspire and inform you. I encourage everyone to innovate in music despite how challenging it can be in our field. In music we not only resist innovation, but we actively teach students to NOT innovate. This is a major hurdle for us in higher education. We must retain that which enhances music careers and add that which enables them.

I hope that my experiences have served to inspire and inform you. I encourage everyone to innovate in music despite how challenging it can be in our field. In music we not only resist innovation, but we actively teach students to NOT innovate. This is a major hurdle for us in higher education. We must retain that which enhances music careers and add that which enables them.