Claudia Taylor “Lady Bird” Johnson High School in San Antonio, Texas, opened in 2008 as the seventh comprehensive high school in the North East Independent School District (NEISD).

I am lucky to be Johnson’s band director since the school opened, and I have worked enthusiastically with our staff and community to grow the music program. I started teaching at Johnson my first year out of college, so I have “grown up” with the campus, and it has been a remarkable journey to see so many lives changed coming through the school’s band program.

Because Johnson was constructed on top of one of the tallest hills in Bexar County, the community dubbed it the “City on the Hill.” The campus is colorful and vibrant to match the wildflowers that Mrs. Johnson shared with the country as first lady. (There’s a Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center at the University of Texas at Austin.) The school opened with about 1,800 students, splitting from Ronald Reagan High School after receiving approval from the community in a 2005 bond. I was a student-teacher at Reagan in 2007, the year prior to the split, and helped navigate the transition for Johnson’s band members from Day One with my friend, mentor and colleague, Alan Sharps, who recently retired after 40 years of teaching. Together, we opened and established the Johnson program.

Looking at an explosion of population on the northside of San Antonio, the NEISD 2005 bond aimed to relieve stress on Reagan, which had a capacity of 3,000 students, but enrollment was approaching 4,000. The initial plans for Johnson provided for a capacity of 3,000 students, but during construction, administrators approved an additional wing that expanded capacity to 3,200. The new campus included a 4,000-square-foot music rehearsal hall.

Looking at an explosion of population on the northside of San Antonio, the NEISD 2005 bond aimed to relieve stress on Reagan, which had a capacity of 3,000 students, but enrollment was approaching 4,000. The initial plans for Johnson provided for a capacity of 3,000 students, but during construction, administrators approved an additional wing that expanded capacity to 3,200. The new campus included a 4,000-square-foot music rehearsal hall.

Because of unprecedented rainstorms in 2006, campus construction fell behind schedule. Johnson opened in 2008, but with only 70% of the campus operational. The cafeteria, athletic fields, auditorium, library and many of the classrooms weren’t functional until Christmas.

However, the show must go on! For our 2008 band camp, the Johnson band rehearsed at neighboring James Madison High School, and we quickly learned that the field was inundated with fire ants. The kids remained positive and had a great sense of humor as they dodged the ant mounds, and the parents worked to eliminate the threat, but the fire ants proved to be worthy adversaries over our two-week camp.

Through most of that first school year, students worked through the challenges of continued construction and a less-than-smooth transition to their new campus, but they maintained the very best attitude. I think the challenges of Johnson’s first year created our culture of flexibility and adaptiveness, which, 12 years later during the COVID-19 pandemic, proved to be invaluable traits to help the band win its first state championship in the face of tremendous adversity.

Less than 10 years after Johnson opened, the school’s music program had grown so much that it required a new hall. During this time, the campus had doubled its instrument inventory but needed more, and music staff expanded from three full-time band directors to four.

Johnson successfully received community support, and in 2018, construction began on an additional $2 million, 3,500-square-foot band hall next to the campus’ existing facility.

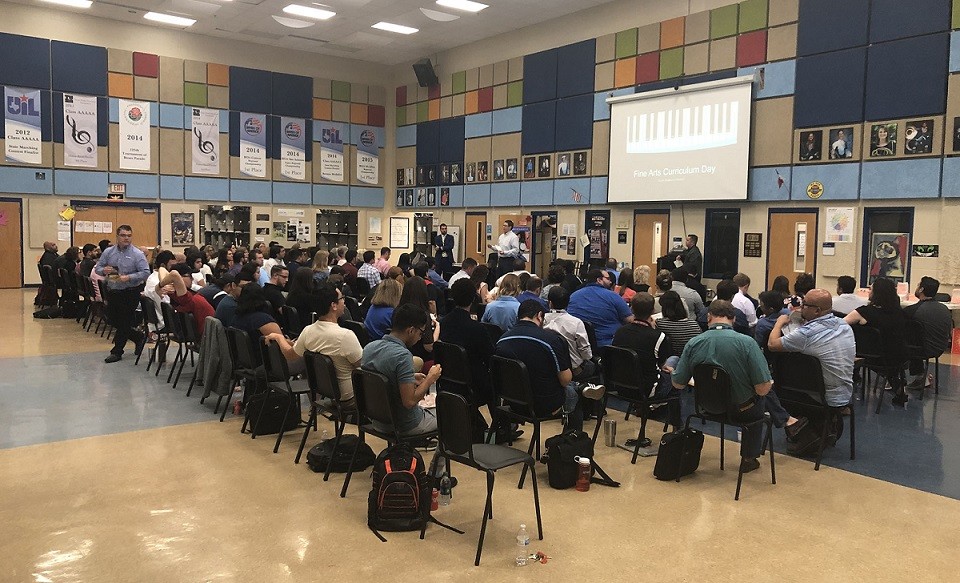

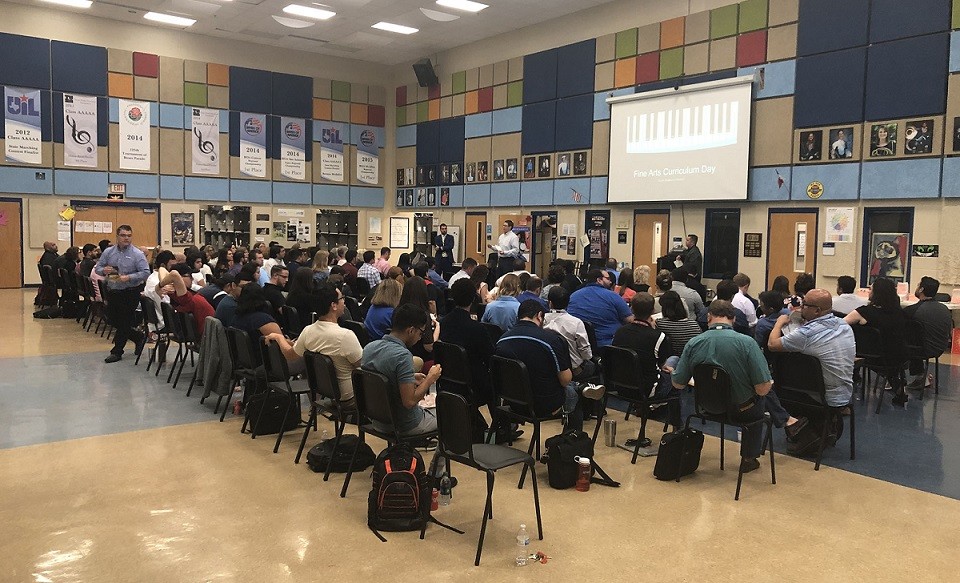

Gain Support by Educating Administrators and the Community

When pursuing anything that involves asking for funding — additional facilities, equipment, staffing, etc. — I find that the single most crucial piece of the puzzle is to patiently educate stakeholders. Administrators and parents may or may not realize your needs until they can see them spelled out clearly with facts and supporting data.

By examining other districts with similar demographics and learning from others, we were able to entice stakeholders to see the value in our proposal. We shared good news about our program’s accomplishments and demonstrated the value of the financial investment, which helped support a growth-minded vision. We began the process by sharing facts and evidence and then followed up patiently and consistently. With time, the Johnson band directors successfully made their case for expansion.

District’s Guiding Principle: Equity

NEISD is a socioeconomically and ethnically diverse district that spans over 144 square miles on the northcentral and northeast side of San Antonio. The district was formed in 1950 and has grown from one high school to seven, 14 middle schools and over 40 elementary schools that serve nearly 68,000 students.

Equity is the guiding principle for the school district. Whenever the district builds a new school, it also targets one of the older schools for additions or demolition and reconstruction. Over the last two decades, NEISD has rebuilt from the ground up two of its original high schools and significantly added to or remodeled four other schools, including Reagan, which opened in 1999.

The district has also torn down and reconstructed several aging middle schools to provide new academic wings, and fine arts and athletic facilities. District planners and leaders meet annually with campus administrators and community members on the (CBAC) to identify new or replacement construction priorities and plan a vision for these subsequent upgrades. In other words, by the time construction is wrapping up on one bond, the district is already preparing to float another to address needs and improve the experience of its students.

Traditionally, when floating a new bond, the district approaches a “wish list” that focuses on seven categories, five physical construction and two related to bond management:

- Safety and security

- Instructional technology

- District operations

- Extracurricular Programs (athletics and fine arts)

- District Facilities

- District Bond program management (financial management)

- Bond Global Contingencies (financial management)

Johnson’s new band hall fell into category #4. Here is the breakdown and project list from the NEISD 2015 bond.

The 10-Year Growth of Johnson’s Band

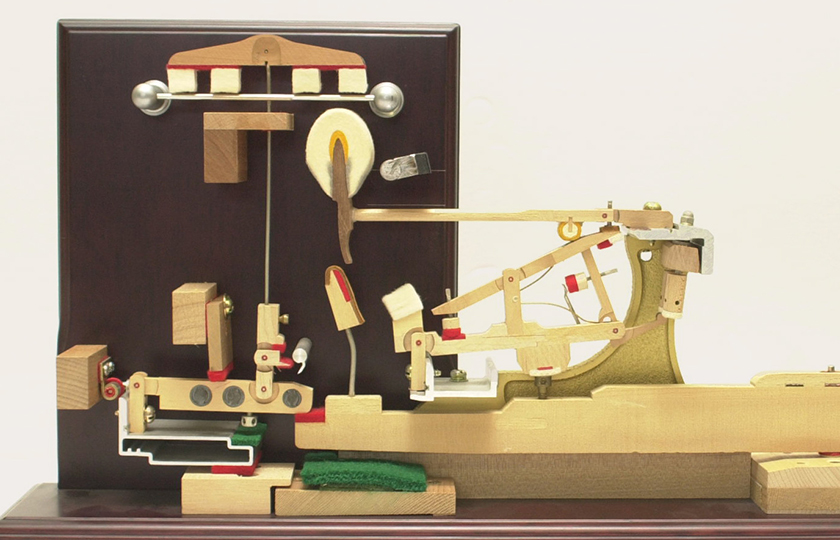

When Johnson opened in 2008, the band hall was built based on the model used in other district high schools. The 3,904-square-foot building had a capacity of 195 students. Johnson also boasted a smaller “ensemble” classroom with an additional capacity of 38 students. The facilities were adequate for the band size of 150 in 2008 and could comfortably accommodate up to 200-250 students.

Year 1, 2008-2009 — 150 students in band: The band opened with smaller junior and senior classes that were split from Reagan, a heathy-sized sophomore class (40-50) mixed from Reagan and and a strong incoming freshman class from Tejeda Middle School (50-60).

Year 2, 2009-2010 — 190 students: With a small senior class graduating from the year before, the band added another healthy freshman class and rapidly approached 200 students.

Years 3 to 5, 2010-2013 — 220 students: With a single middle school feeder, the Johnson band stabilized at around 220 total students with four full classes that ranged in size from 40 to 60 students in each grade. Growth had stagnated in the North San Antonio area due to the economic downturn of 2008-2009, and the school enrollment remained flat at around 2,500 students.

During the fall of 2011, NEISD narrowly passed a bond that included the construction of the district’s 14th middle school, which would be a second dedicated feeder for Johnson. The construction of the new middle school was controversial because several of the middle schools surrounding Johnson had plenty of capacity, and growth in the North San Antonio area was reasonably flat to negative.

Fortunately for the Johnson band, the construction meant a new infusion of numbers and talent. Instead of 300 students in a single middle school band, future projection models showed 550 to 600 students in two middle school bands.

Years 4 to 8, 2013-16 — 260 students: As the economy recovered, construction of new homes in the Johnson attendance zone began to grow gradually. Tex Hill opened in the fall of 2014, just three years after the bond passed to build the campus.

In the fall of 2013, the Johnson band exceeded 250 students, and rehearsing the entire marching band together indoors became impossible. The band started utilizing orchestra, choir and any available spaces in the fine arts wing during the school day.

Our color guard numbered 40 members for the 2013-2014 school year, and the entire team could not rehearse inside the current band hall due to space constraints. With the campus growing, gym space was at a premium, and our color guard often had to split into two groups to rehearse. Half of the flag students would be inside with the color guard director; the other half was outside, rehearsing with student leadership and a band director supervising.

After Hill opened, Tejeda continued to flourish, and projections based on retention and the 2014 size of the sixth-grade class between the two middle schools showed that the Johnson band would reach 350 students within three years.

We shared the 2014 projections that forecasted that the incoming 6th-grade band class would nearly double — from 100 beginners to 200 — and demonstrated the down-the-line impact on Johnson High School’s band program.

We initially requested a portable for additional rehearsal space during the day. But, as the CBAC was meeting in the fall of 2014 to discuss floating another bond in 2015, we began to discuss the idea of expanding the band hall capacity at Johnson and other campuses in the district that were seeing similar growth.

The CBAC identified Reagan, Johnson and Winston Churchill high schools for band hall expansion projects on the 2015 bond. Legacy of Educational Excellence (LEE) and MacArthur High would also receive upgrades to their band and fine arts facilities, but not additional capacity, with bond funds. Theodore Roosevelt High School had already received a new fine arts facility in 2008, and Madison welcomed a new fine arts facility as a part of the 2011 bond. In the end, the district listened to its teachers, band parents and administrators and significantly improved the fine arts facilities at all seven high school campuses.

The CBAC identified Reagan, Johnson and Winston Churchill high schools for band hall expansion projects on the 2015 bond. Legacy of Educational Excellence (LEE) and MacArthur High would also receive upgrades to their band and fine arts facilities, but not additional capacity, with bond funds. Theodore Roosevelt High School had already received a new fine arts facility in 2008, and Madison welcomed a new fine arts facility as a part of the 2011 bond. In the end, the district listened to its teachers, band parents and administrators and significantly improved the fine arts facilities at all seven high school campuses.

Year 9, 2016-2017 — 303 students: The Johnson program surpassed 300 students in the band as projected.

Year 10, 2017-2018 — 350 students: Contractors broke ground on Johnson’s new band hall at the end of the school year in 2018 and completed the project in the summer of 2019, in time for the 2019-2020 school year. The new facility added nearly 3,500 square feet of space and an additional capacity of 175 students. It included a small classroom for instruction, a new office, a new storage room and additional instrument locker storage. The original architect for Johnson High School also designed the addition to provide for continuity. The addition looks like it was there from Day One.

The larger Johnson band has benefited tremendously from the additional capacity granted through the 2015 bond. With the new facility, the capacity at Johnson is over 400 students now. All band students also have enough locker space for equipment.

With COVID-19 challenges, the additional space was invaluable as we split bands into smaller groups. Band enrollment dipped to 310 due to the pandemic, but numbers have bounced back, and we are currently sitting at 335 for the 2021-2022 school year.

Staffing and Team Teaching

As we approached an enrollment of 300 students in the 2015-2016 school year, we met with our principal and requested hiring a fourth band director. Our orchestra program was also growing, so administrators decided to support both disciplines and hire a single director who would split time between band and orchestra. The additional staff member was a blessing in managing the transition from 290 students to 350 in the band and the orchestra’s growth to 150 students.

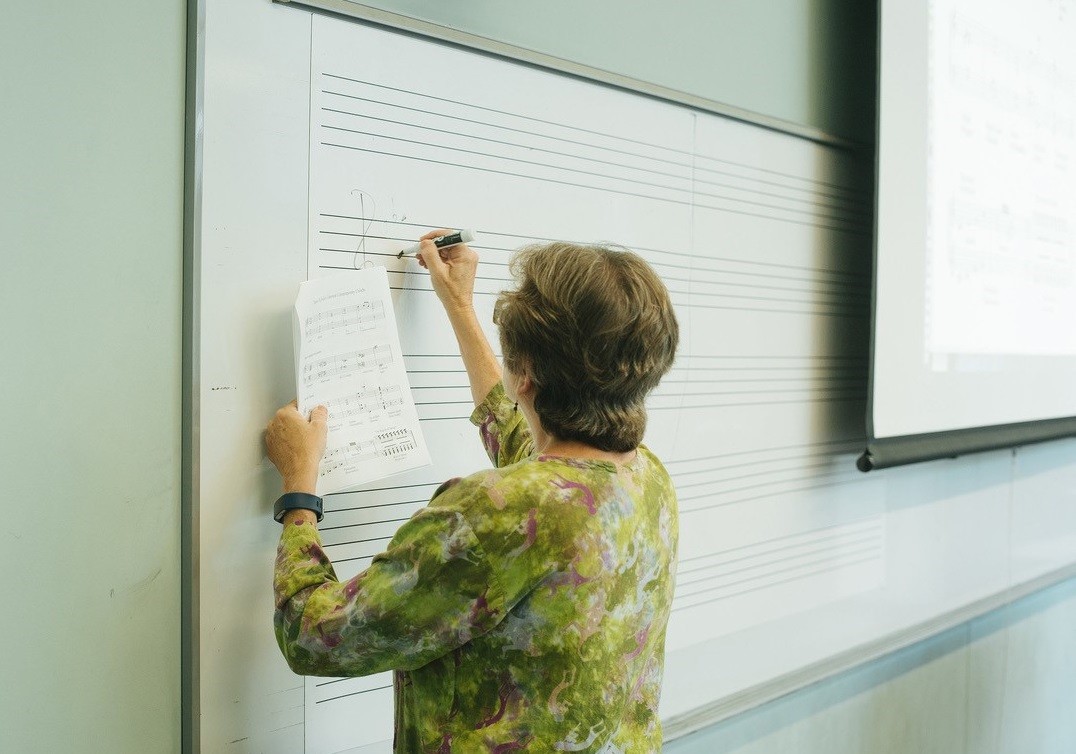

The four directors at Johnson work together closely, but each has a defined role. I am the Head Director, which is like the CEO of a corporation. I chart the overall course for the program, manage communication, coordinate fundraising and engage with the middle schools daily to recruit and retain students. I also conduct the wind ensemble/honor band and direct and program the marching band. The Associate Director, which was the position Mr. Sharps held, is the eyes and ears of the program and has his/her hand in everything the Head Director does, but also focuses on the jazz program and co-conducts the wind ensemble/honor band.

The two Assistant Directors manage the inventory and music library, and they conduct the non-varsity and sub non-varsity concert bands. The Assistant Director for Percussion teaches percussion for grades 6-12 and manages building events/facilities. The Assistant Director for Band and Orchestra co-conducts the full orchestra and teaches music theory.

We team teach all the concert bands, even though someone will ultimately conduct them at University Interscholastic League (UIL) Marching Band Contests. By taking this team approach, our students benefit from the strengths and personality that each director brings to the table.

If it’s not possible to have a team of directors at your high school, or if you’re limited to one assistant, try to team teach as much as possible with other music teachers in your district or department. Bring together choir, orchestra and band, or team teach with the middle schools. Band directing can be lonely, and having one or more partners is powerful.

Growing the Instrument Inventory

When the Johnson campus opened in 2008, the construction project was over budget due to the additional G-Wing added to the campus midway through. This resulted in across-the-board cuts to equipment purchases, including musical instruments, chairs, stands and more.

The band opened with enough instruments for a program of 150-175 students and shared equipment with Reagan. As Johnson’s program grew, administrators promised to allocate monies each year to purchase additional instruments to bring the equipment capacity to match the 350-member Reagan inventory before the split.

As other schools in our district saw their band programs declining, administrators permitted Johnson to borrow out-of-circulation instruments from those campuses. From 2008 to 2015, Johnson slowly added to its inventory while continuing to borrow from other campuses to meet our needs. By 2015, the band inventory matched the one at Reagan, and we began to focus on replacements and upgrades.

We constantly communicated with administration and other band directors to borrow out-of-use instruments on other campuses and maximize the use of resources. Today, this practice continues in our district as schools regularly share equipment to save money and apply toward replacement and upgrades. We have been careful to service, clean and maintain our original inventory since 2008 so that instruments did not fall into disrepair. Now, we work with our middle schools in our cluster to identify needs that will benefit all three schools before we purchase additional instruments.

Pay It Forward

Our earliest goal was for Johnson to serve as a shining “City on the Hill” full of positive energy for music education. We realized the unique privilege afforded to us by our community and that our challenges were unique to our situation. But our hope was to share what we learned through the process of building a successful program from scratch and to drive conversations about the “what ifs.”

Mr. Sharps and I are both non-native Texans — we did not grow up in the UIL or Texas band culture, but we came here to learn and be a part of it. I believe that Johnson has benefited from our desire to bring together multiple schools of thought from all over the country, and I encourage band directors to learn from great programs in every city and every state. In our view, success is not dictated by trophies or accolades. Often our greatest success as music educators is rooted in the small “gems” that we learn from one another’s programs.

Johnson regularly engages four to five student teachers each year in hopes of giving back to the music education community and ensure that we support the future of our profession. We are always open to visitors. We share our ideas and give generously as so many have helped us, and we hope that the ideas we have provided will help someone else grow and improve their music program.

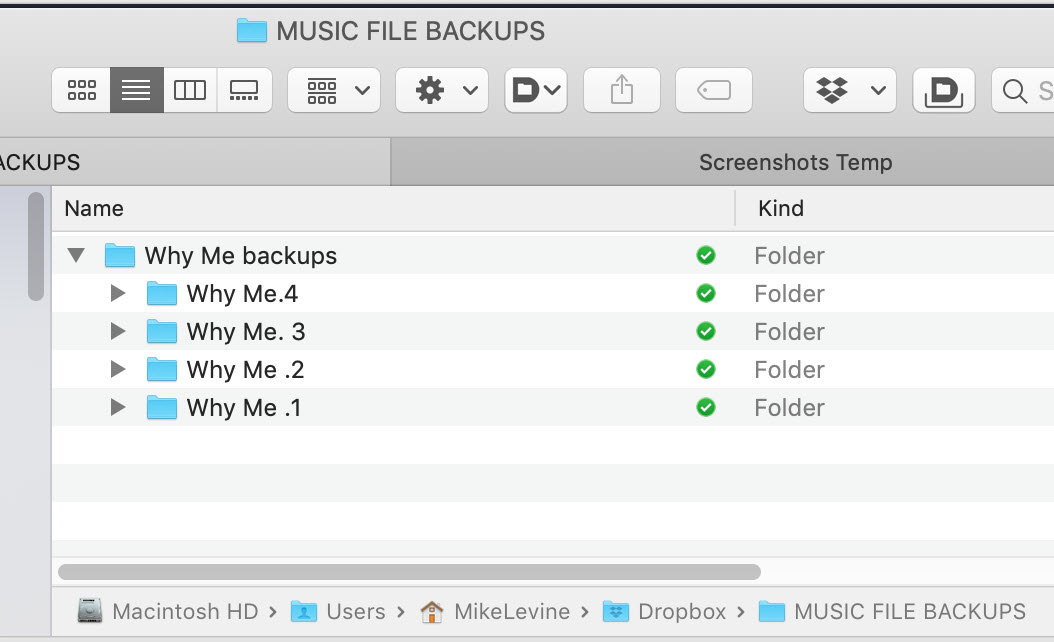

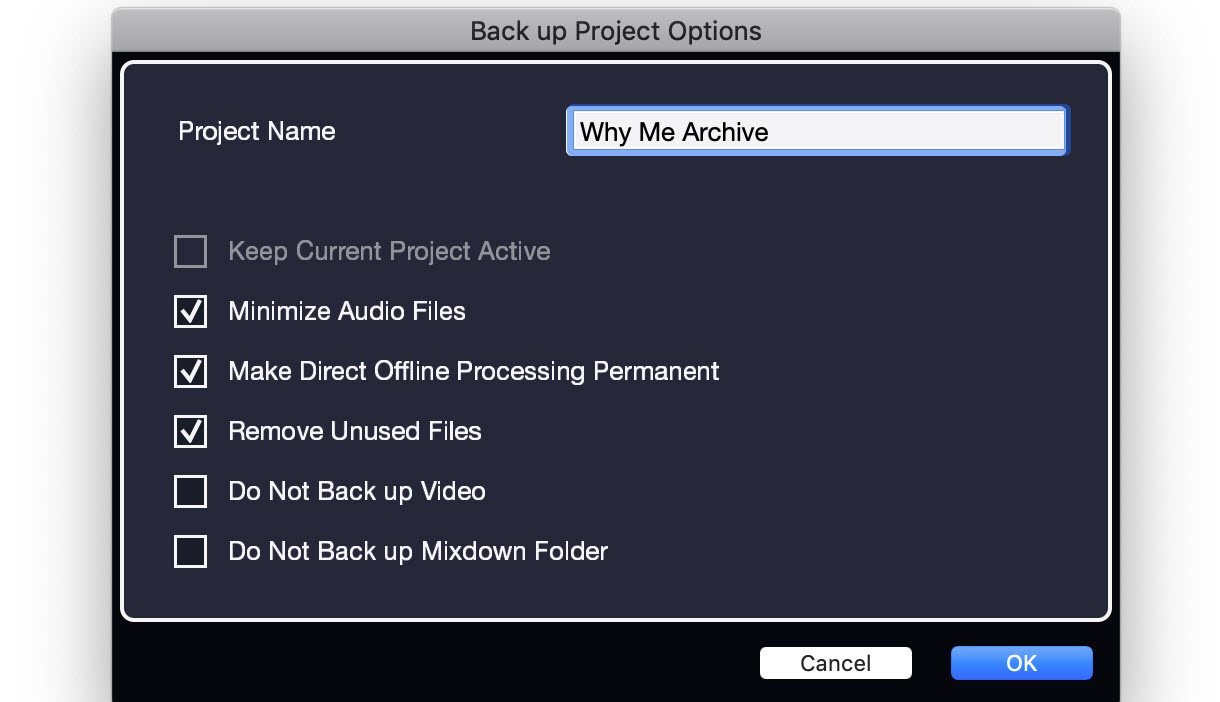

It was impossible to do the necessary legwork during the school year, so my husband, Kris Antonetti, and I worked in the buildings during the summer when the air conditioning was not turned on. At the time, we only had desktop computers — no laptops or tablets — so we started in the hot storage room, writing down instrument model numbers and serial numbers on a yellow legal pad. Then we went back to my office to input this information on my computer. We spent hours doing this.

It was impossible to do the necessary legwork during the school year, so my husband, Kris Antonetti, and I worked in the buildings during the summer when the air conditioning was not turned on. At the time, we only had desktop computers — no laptops or tablets — so we started in the hot storage room, writing down instrument model numbers and serial numbers on a yellow legal pad. Then we went back to my office to input this information on my computer. We spent hours doing this. We started with the problems I faced and then gathered ideas from other directors to see what was needed most. Many of our music education friends faced similar challenges in their classrooms. We wanted to focus on the inventory aspect of organization, so we started developing instrument and uniform management as well as the ability to check these items out to students and to organize students into ensembles.

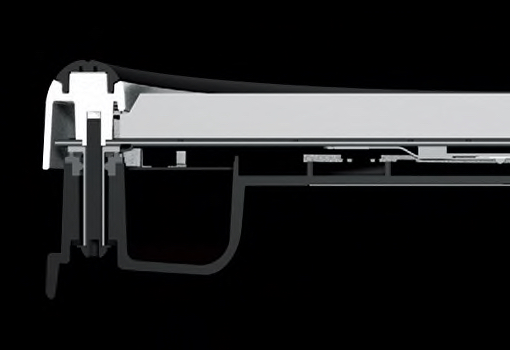

We started with the problems I faced and then gathered ideas from other directors to see what was needed most. Many of our music education friends faced similar challenges in their classrooms. We wanted to focus on the inventory aspect of organization, so we started developing instrument and uniform management as well as the ability to check these items out to students and to organize students into ensembles. We met with Dave Gnojek, the associate design director at

We met with Dave Gnojek, the associate design director at

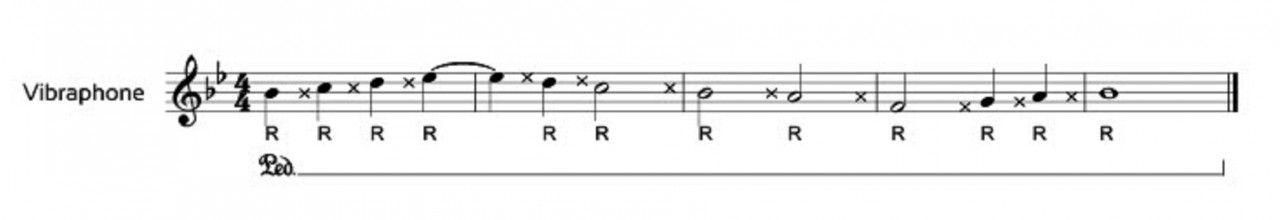

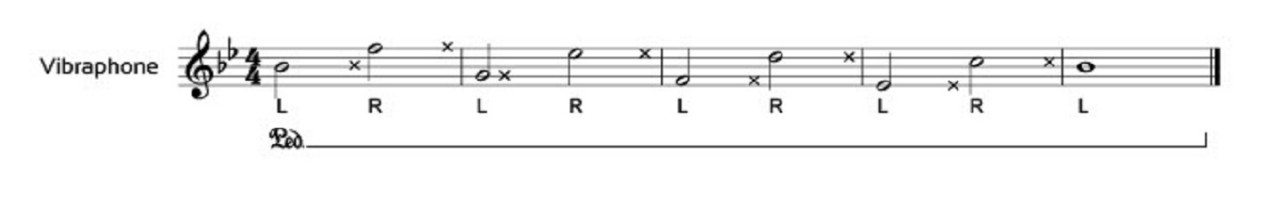

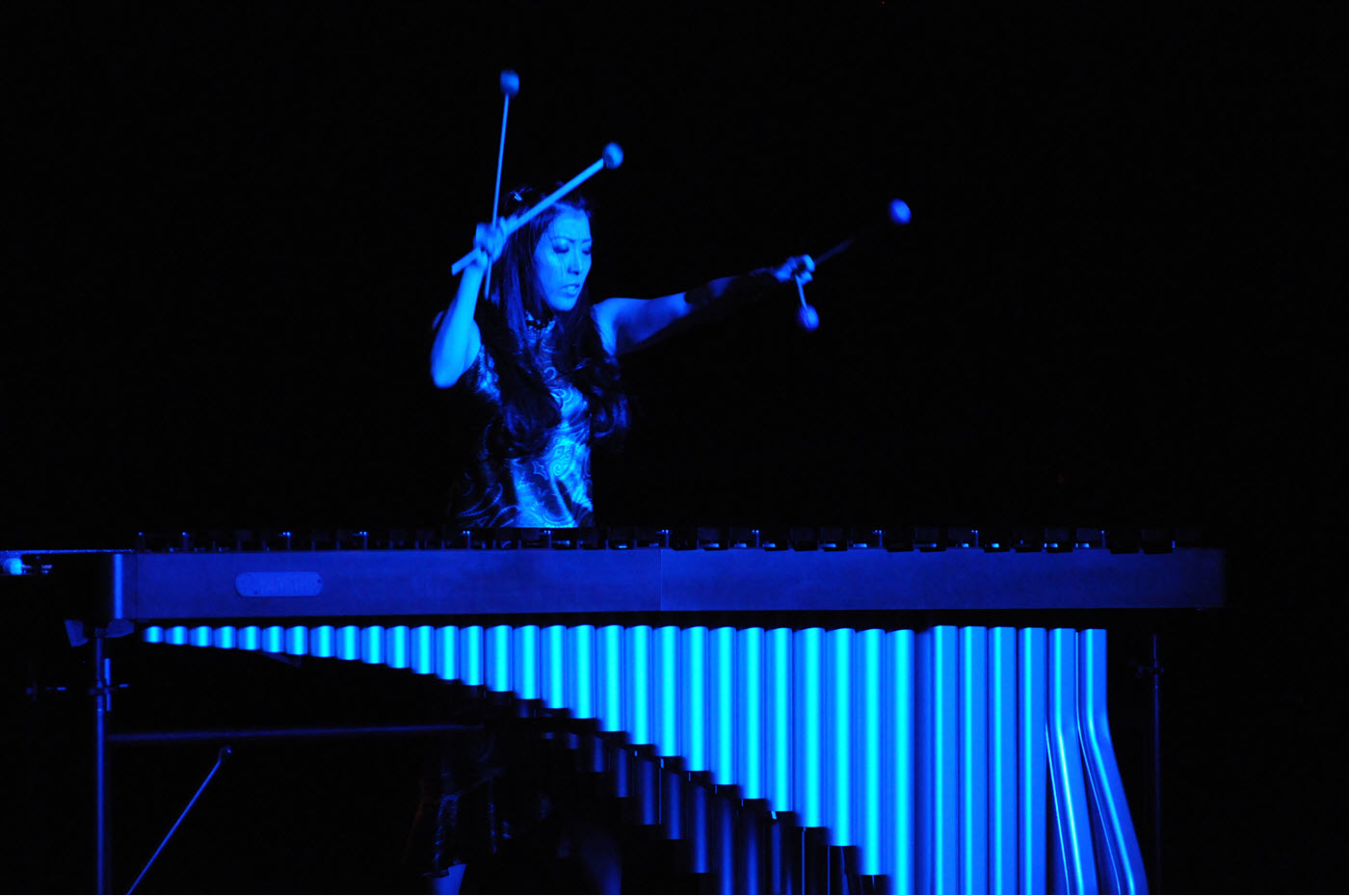

Fix It: Mallet Placement and Equal Right-to-Left-Hand Involvement

Fix It: Mallet Placement and Equal Right-to-Left-Hand Involvement

Populations in rural communities tend to be stable. Many of your colleagues and your students have years of community and institutional knowledge. Many students have had the same educator group since kindergarten. They will be curious about you, and the more comfortable you are answering their questions, the more successful you will be. I start every year at

Populations in rural communities tend to be stable. Many of your colleagues and your students have years of community and institutional knowledge. Many students have had the same educator group since kindergarten. They will be curious about you, and the more comfortable you are answering their questions, the more successful you will be. I start every year at

The Happiness Mix Project

The Happiness Mix Project Once students can tell a sad song from a scary song from a happy song, he says, “I would say, let’s recognize we can use songs to feel better when we feel sad, and start asking the ‘why’ questions.”

Once students can tell a sad song from a scary song from a happy song, he says, “I would say, let’s recognize we can use songs to feel better when we feel sad, and start asking the ‘why’ questions.”

Looking at an explosion of population on the northside of San Antonio, the NEISD 2005 bond aimed to relieve stress on Reagan, which had a capacity of 3,000 students, but enrollment was approaching 4,000. The initial plans for Johnson provided for a capacity of 3,000 students, but during construction, administrators approved an additional wing that expanded capacity to 3,200. The new campus included a 4,000-square-foot music rehearsal hall.

Looking at an explosion of population on the northside of San Antonio, the NEISD 2005 bond aimed to relieve stress on Reagan, which had a capacity of 3,000 students, but enrollment was approaching 4,000. The initial plans for Johnson provided for a capacity of 3,000 students, but during construction, administrators approved an additional wing that expanded capacity to 3,200. The new campus included a 4,000-square-foot music rehearsal hall.

The CBAC identified Reagan, Johnson and

The CBAC identified Reagan, Johnson and

Thankfully, our district had recently made the music librarian the de facto music coordinator for the district, so I went to him and asked for his help and support. Additionally, I came up with several plans of my own. I was not allowed to charge band participation fees, but I could charge instrument rental fees. We have some instruments in the district rental pool, and some instruments at the schools. For the school instruments, I could charge the same rental fees as the district, and I used that money to fund a repair and supply budget. This went into effect almost immediately.

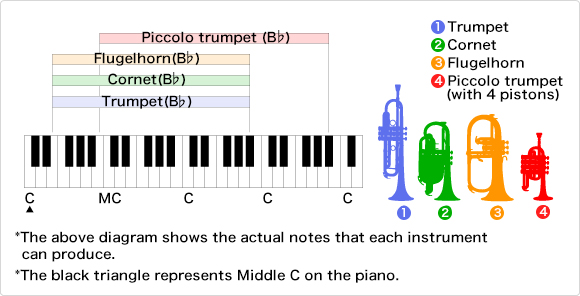

Thankfully, our district had recently made the music librarian the de facto music coordinator for the district, so I went to him and asked for his help and support. Additionally, I came up with several plans of my own. I was not allowed to charge band participation fees, but I could charge instrument rental fees. We have some instruments in the district rental pool, and some instruments at the schools. For the school instruments, I could charge the same rental fees as the district, and I used that money to fund a repair and supply budget. This went into effect almost immediately. To recruit students for the beginning band at Meadows Elementary, I made sure to talk to all 5th graders on the third day of school along with the elementary strings teacher. She played her instruments, and I played several winds instruments including clarinet, trombone and trumpet. We answered questions and handed out interest forms, which also helped with instrumentation as we could assign students to their first or second instrument choices.

To recruit students for the beginning band at Meadows Elementary, I made sure to talk to all 5th graders on the third day of school along with the elementary strings teacher. She played her instruments, and I played several winds instruments including clarinet, trombone and trumpet. We answered questions and handed out interest forms, which also helped with instrumentation as we could assign students to their first or second instrument choices. With each year of experience, I have gained more confidence as a music educator and have found better ways to be effective, efficient, and to challenge and support my students in the classroom. I have brought in guests from universities and local businesses to talk to my students and broaden their understanding of music. I have commissioned new works for my band as part of a consortium. I have taken my groups to festivals, tours and on trips to enrich their band experience. I just want to continue to challenge my students and let them experience life through the power of music.

With each year of experience, I have gained more confidence as a music educator and have found better ways to be effective, efficient, and to challenge and support my students in the classroom. I have brought in guests from universities and local businesses to talk to my students and broaden their understanding of music. I have commissioned new works for my band as part of a consortium. I have taken my groups to festivals, tours and on trips to enrich their band experience. I just want to continue to challenge my students and let them experience life through the power of music.

In past years, Zeilinger has even taught hand bell and steel drums when students express the desire. “When I see the interest, I’m going to go down that path because I want my students’ high school experiences to be memorable. … My program is really focused on developing the desire among students to pursue something they’re passionate about.”

In past years, Zeilinger has even taught hand bell and steel drums when students express the desire. “When I see the interest, I’m going to go down that path because I want my students’ high school experiences to be memorable. … My program is really focused on developing the desire among students to pursue something they’re passionate about.” Starting in the 2021-2022 school year, students will have the option to participate in the academy and benefit from a field trip to the

Starting in the 2021-2022 school year, students will have the option to participate in the academy and benefit from a field trip to the

Often, teachers are intrinsically driven to make the favored ensemble from their past the highest quality possible because they have such a clear picture of what they want, they know what success looks like, and they have a strong connection to that particular ensemble.

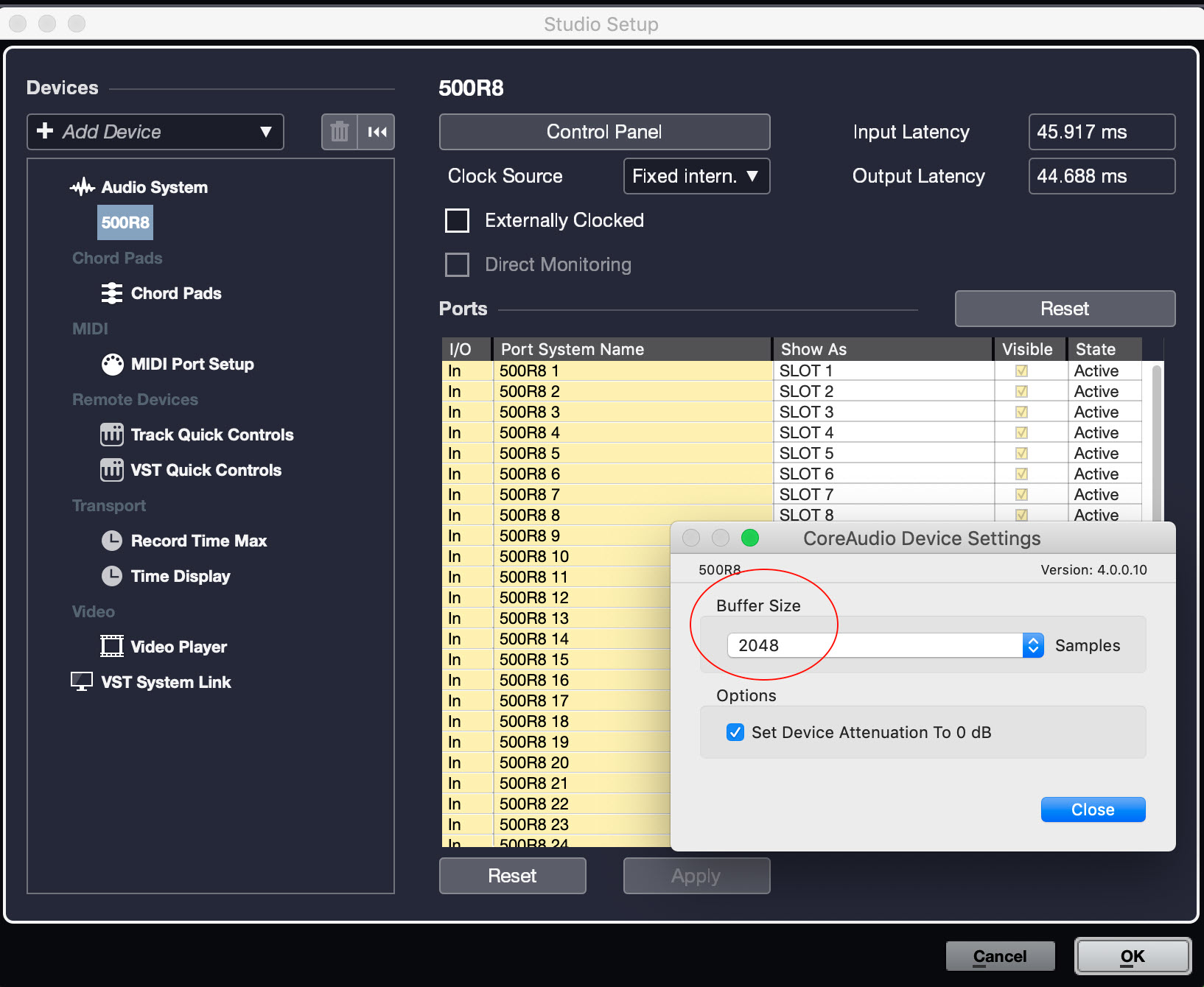

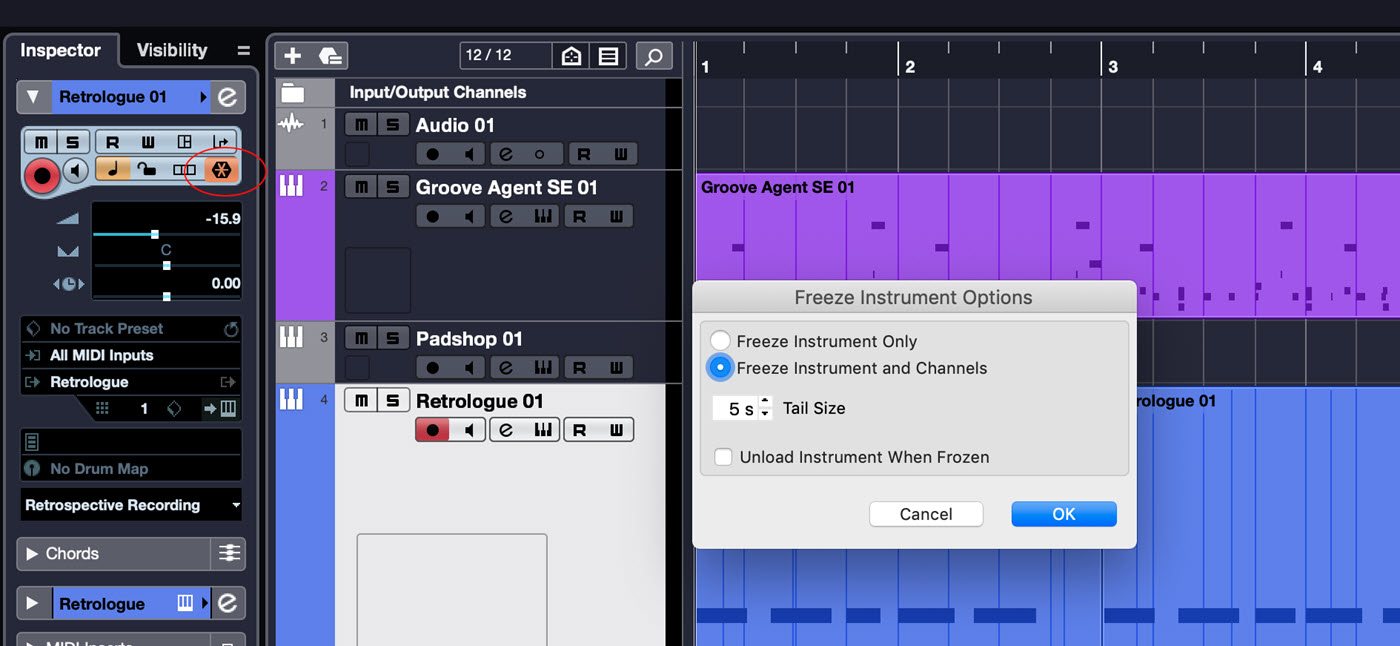

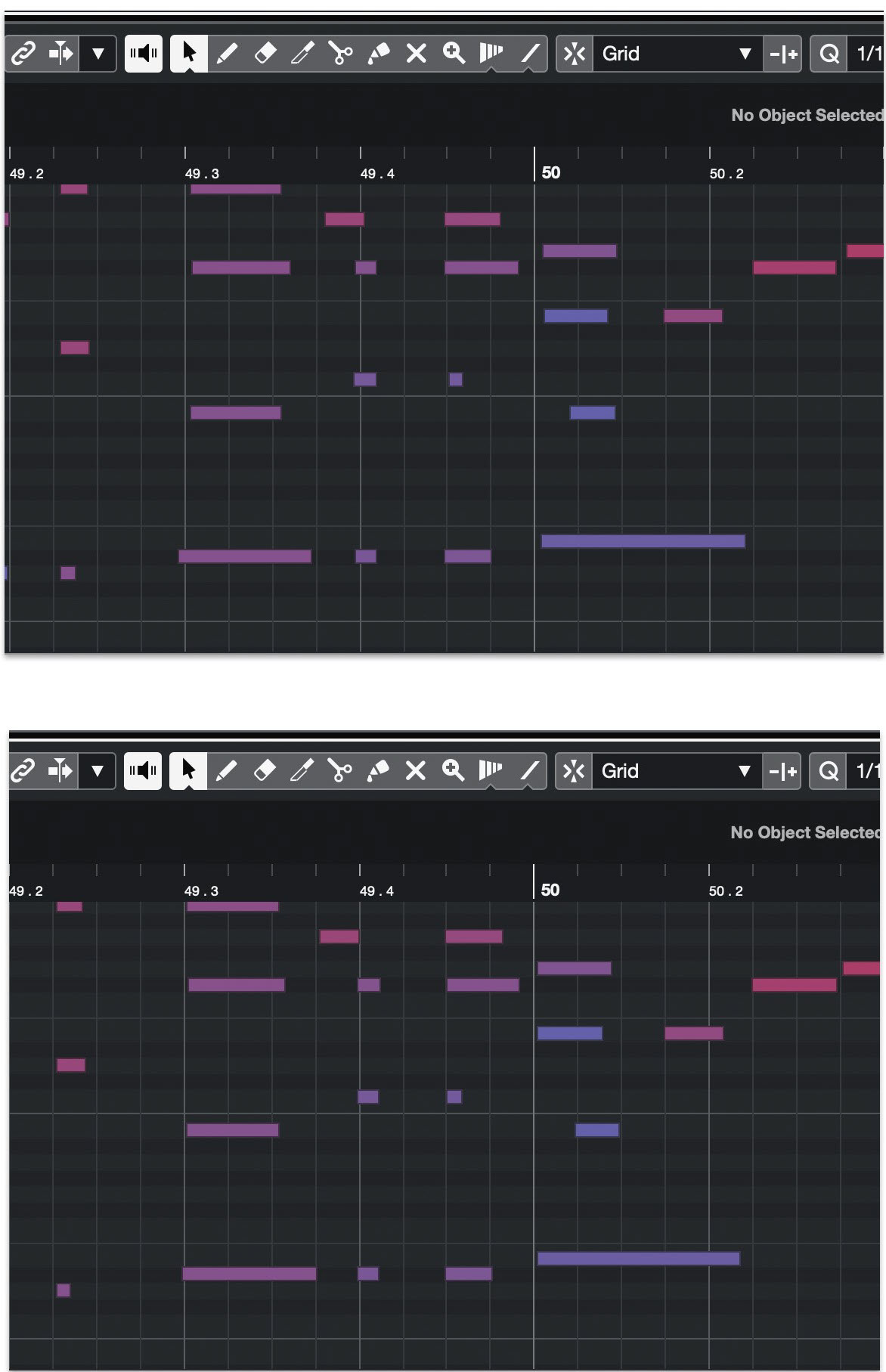

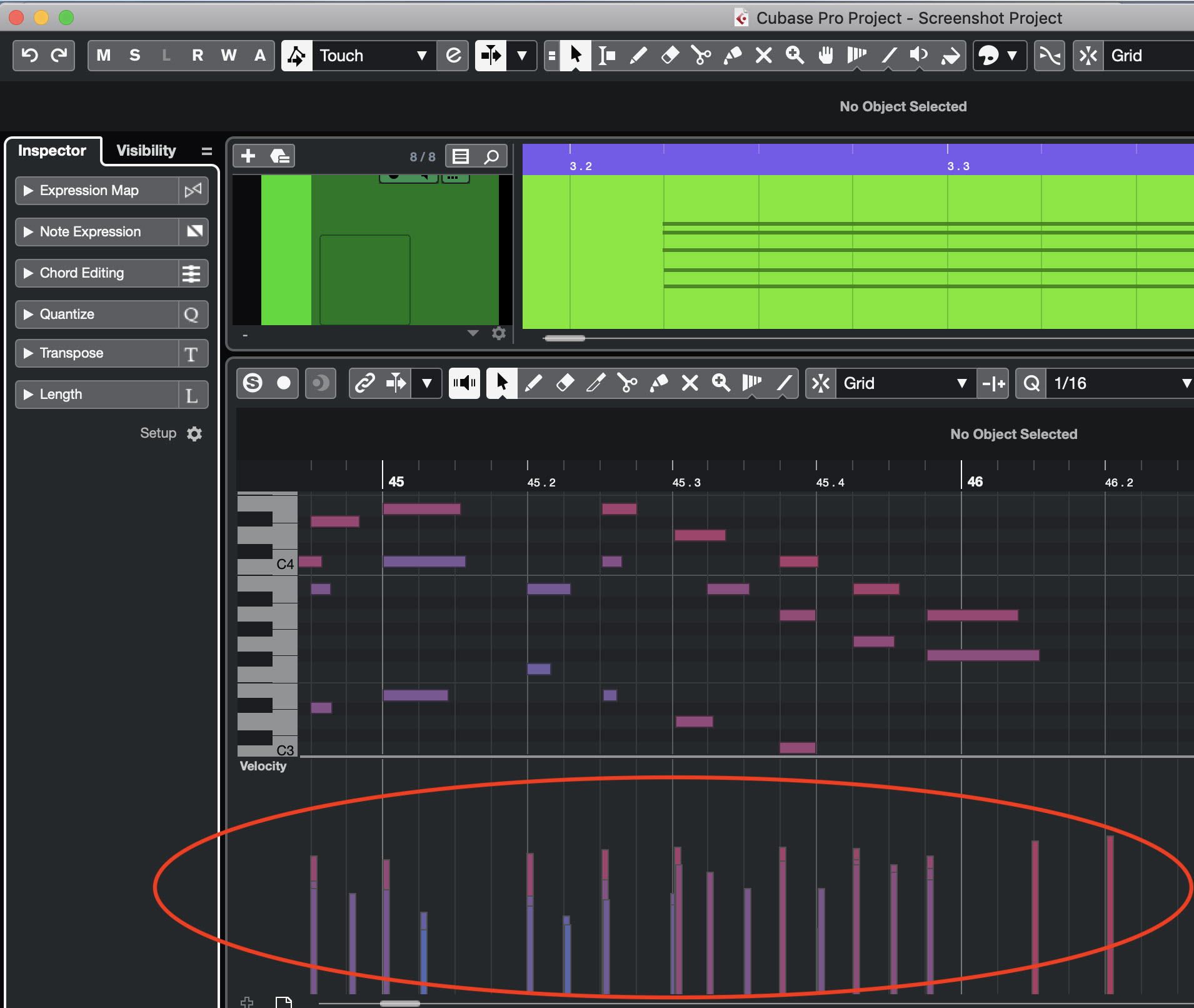

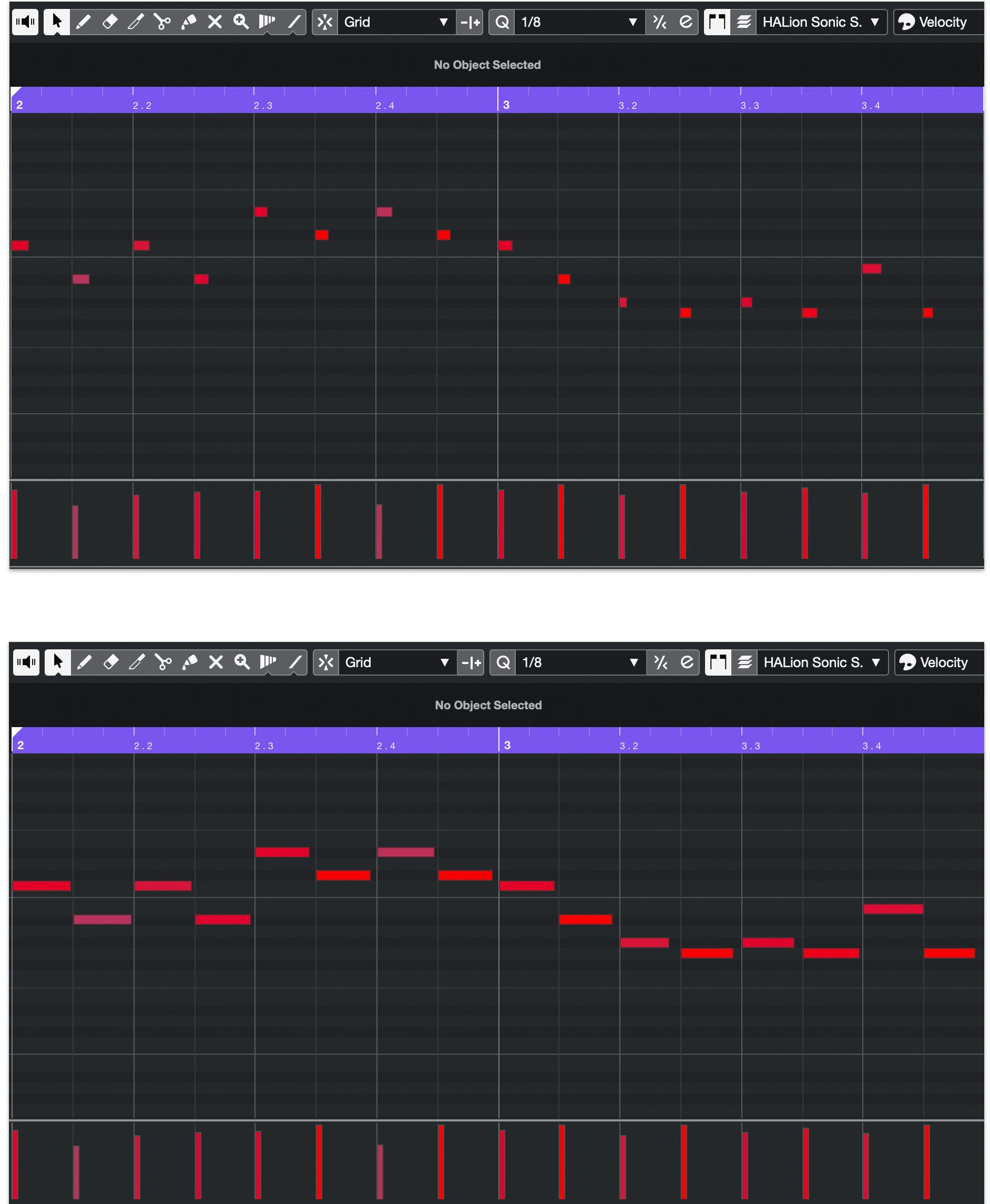

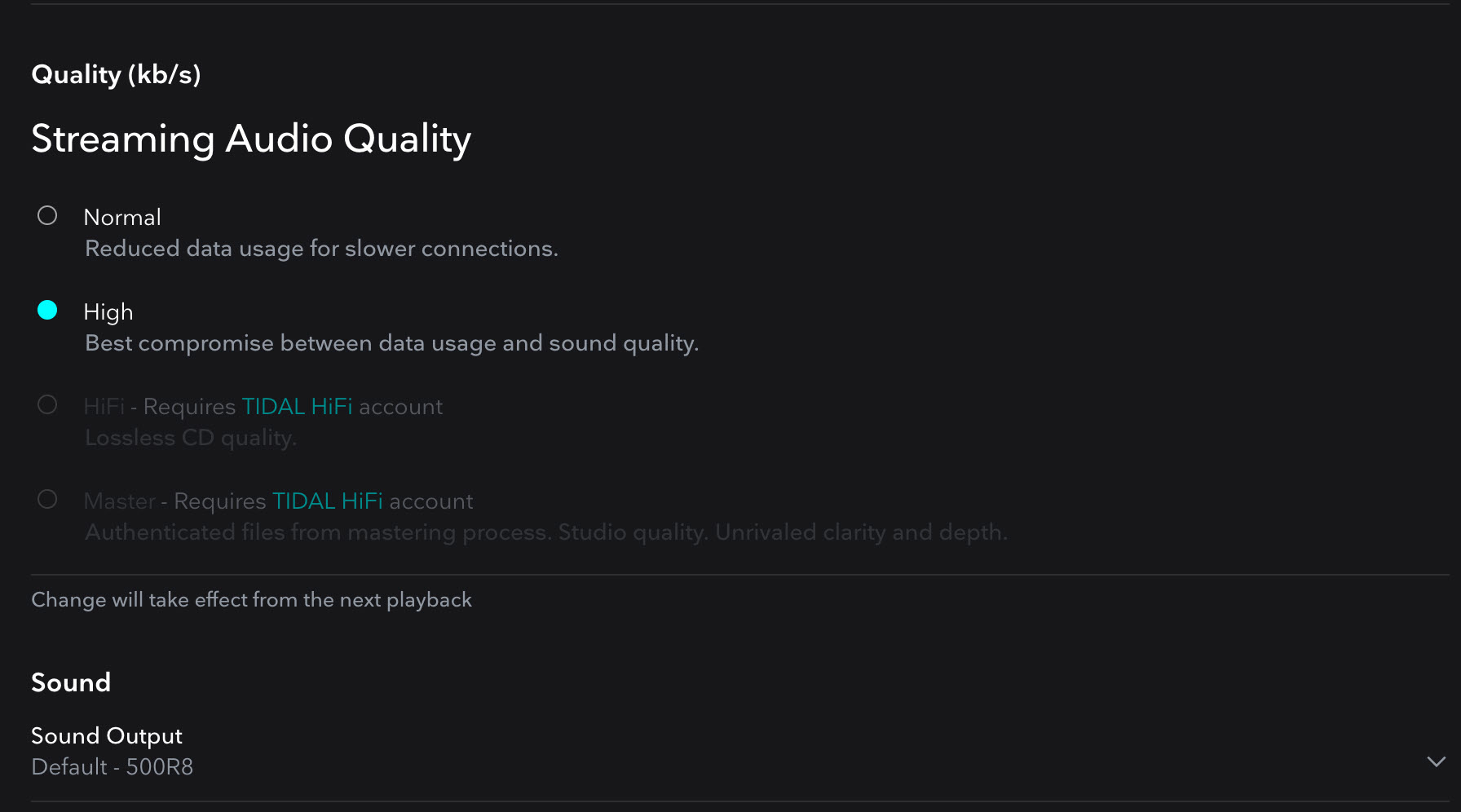

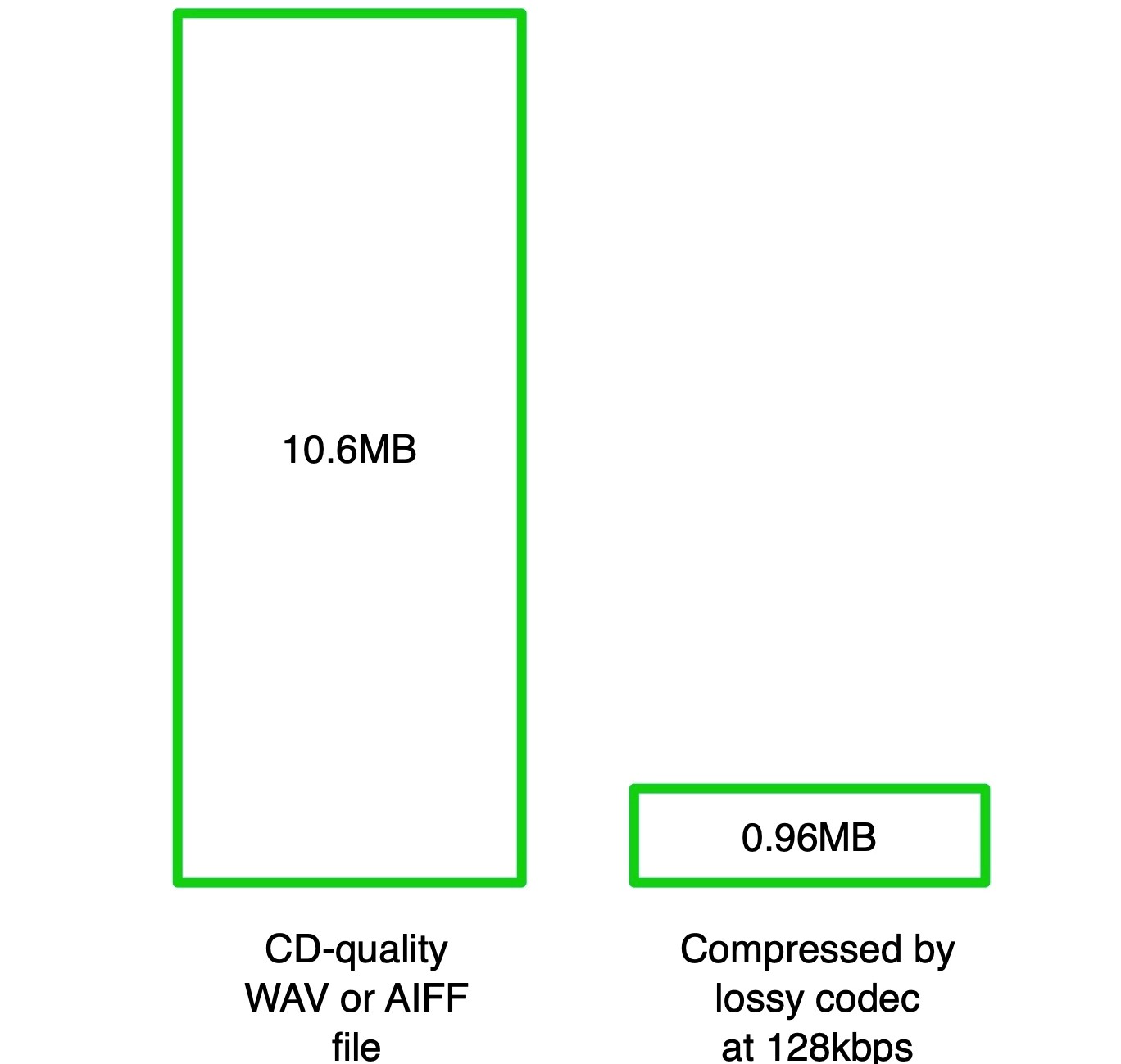

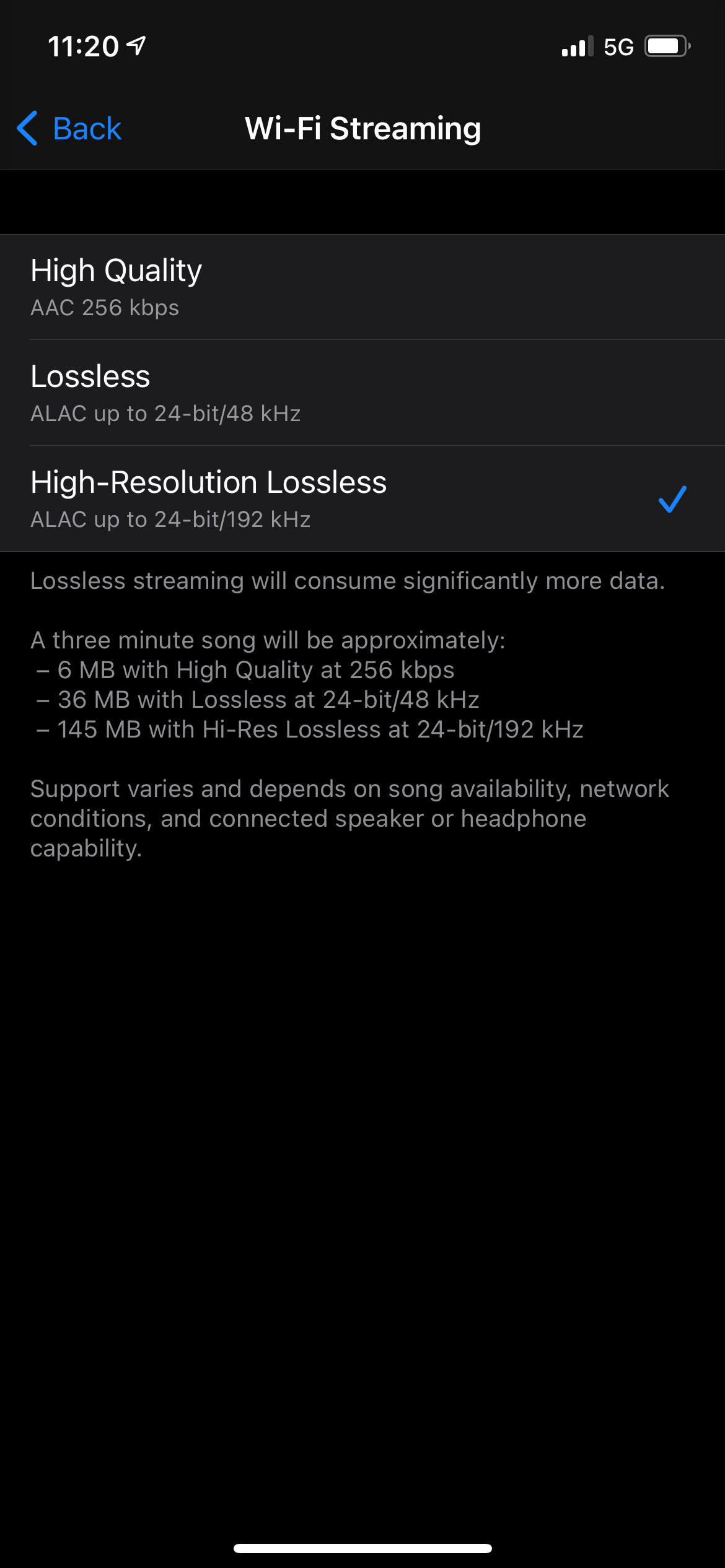

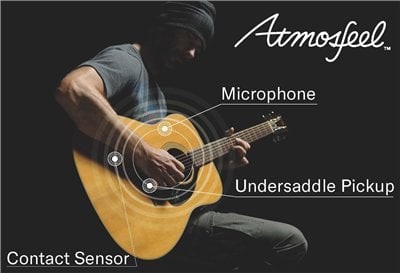

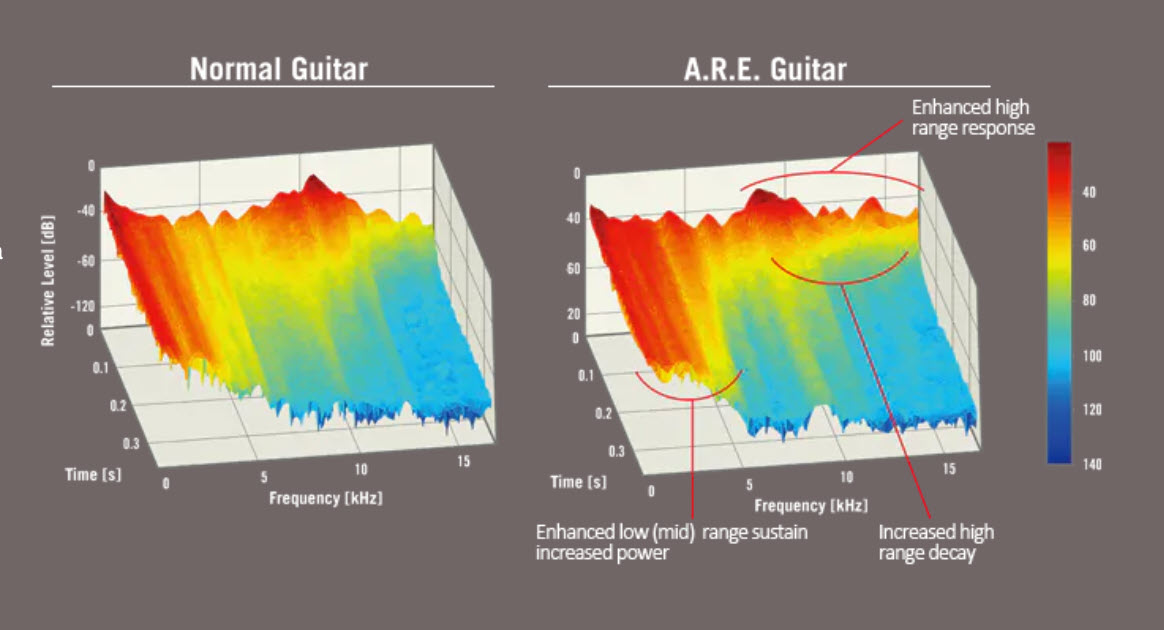

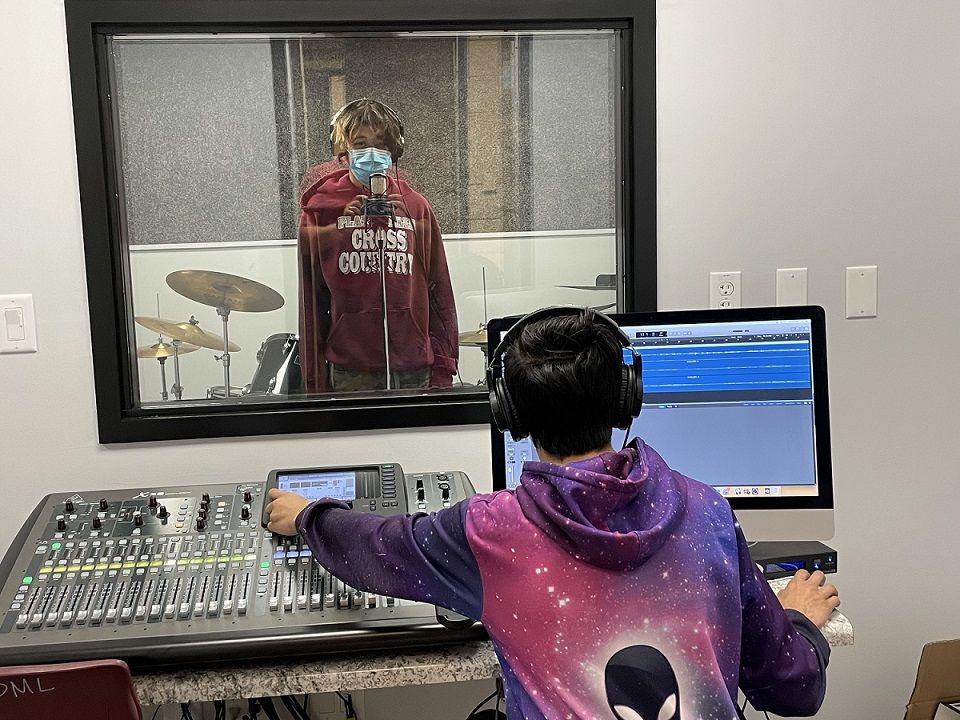

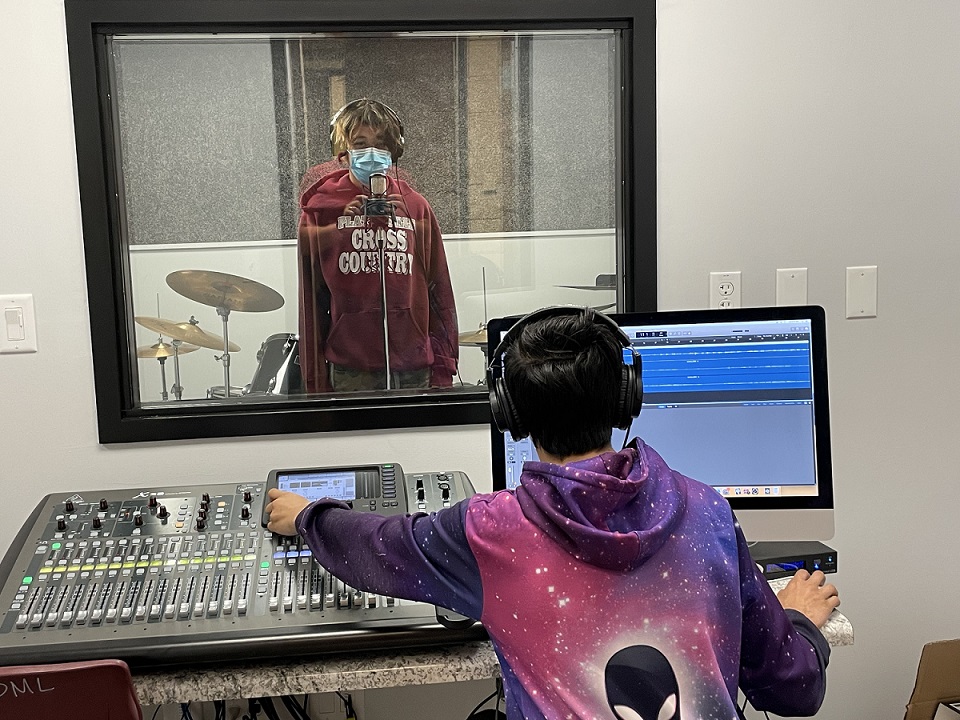

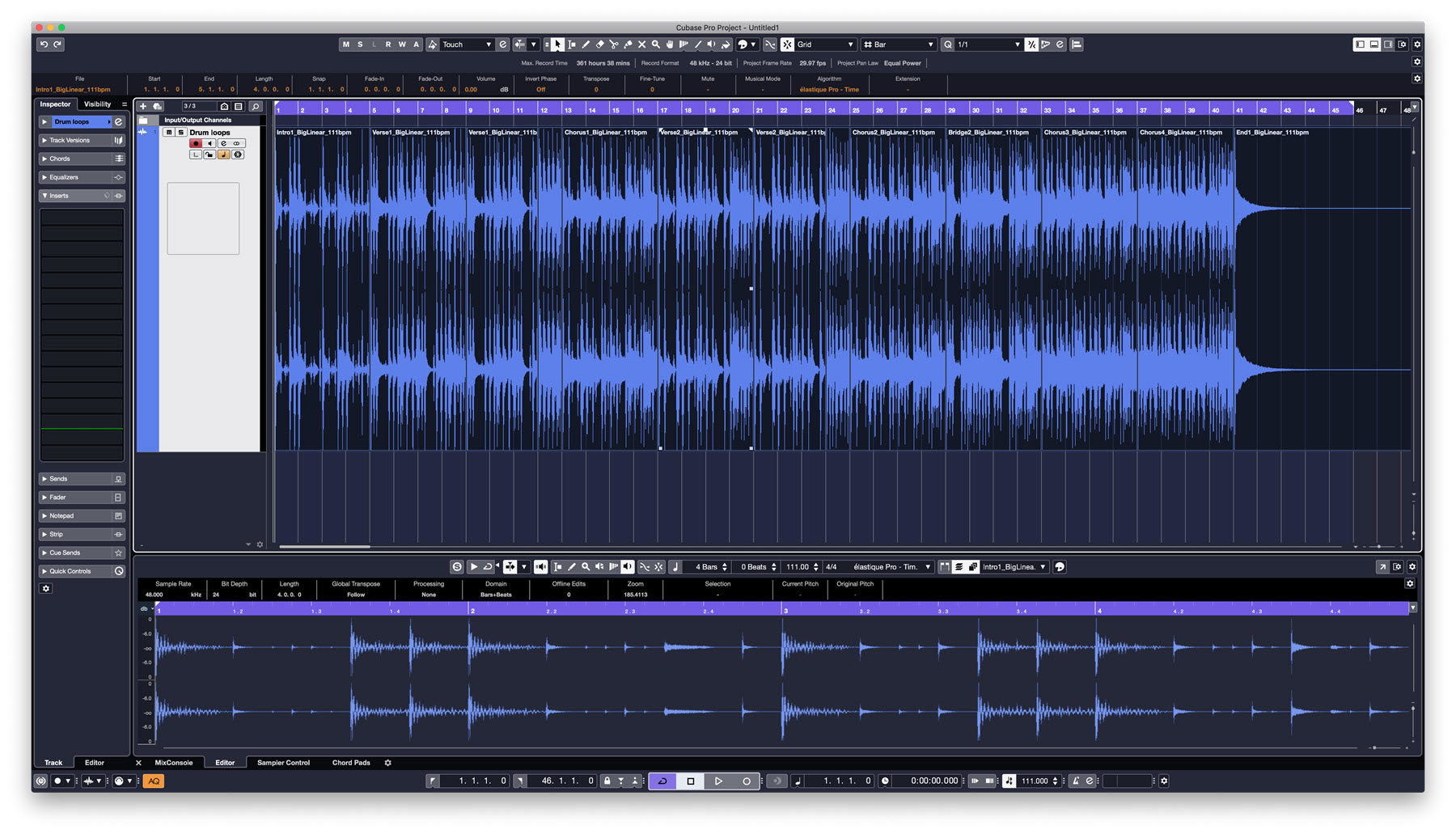

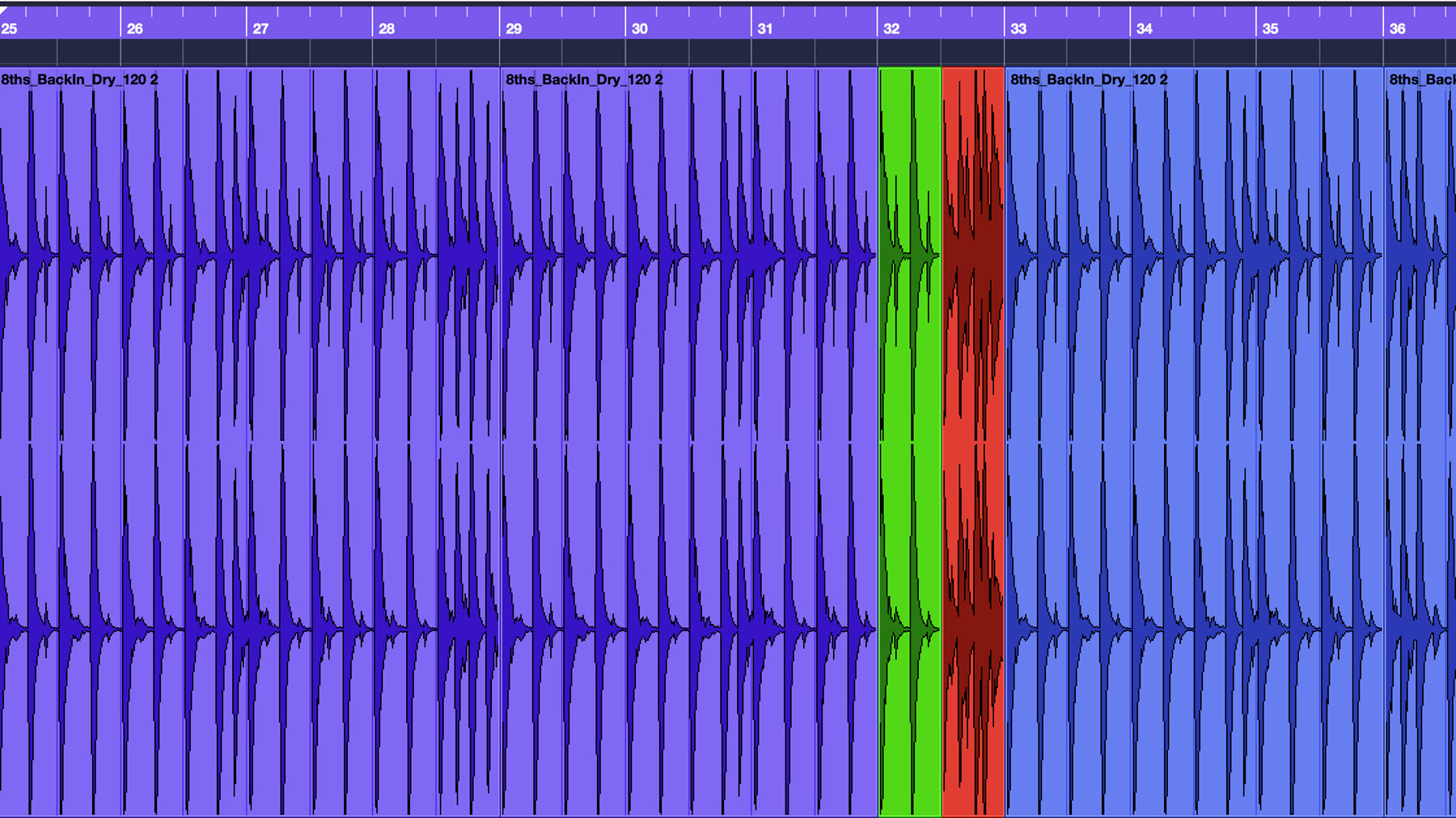

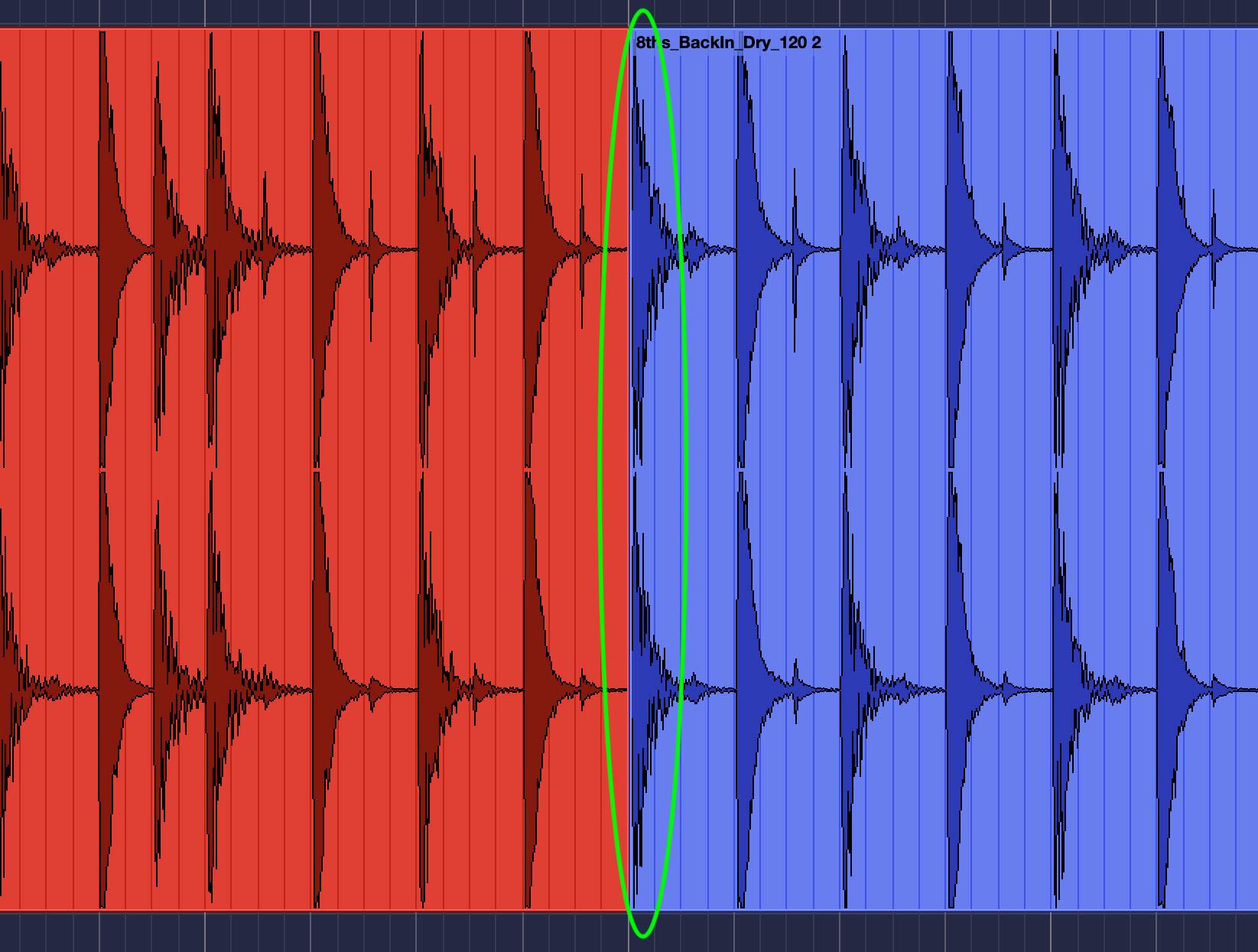

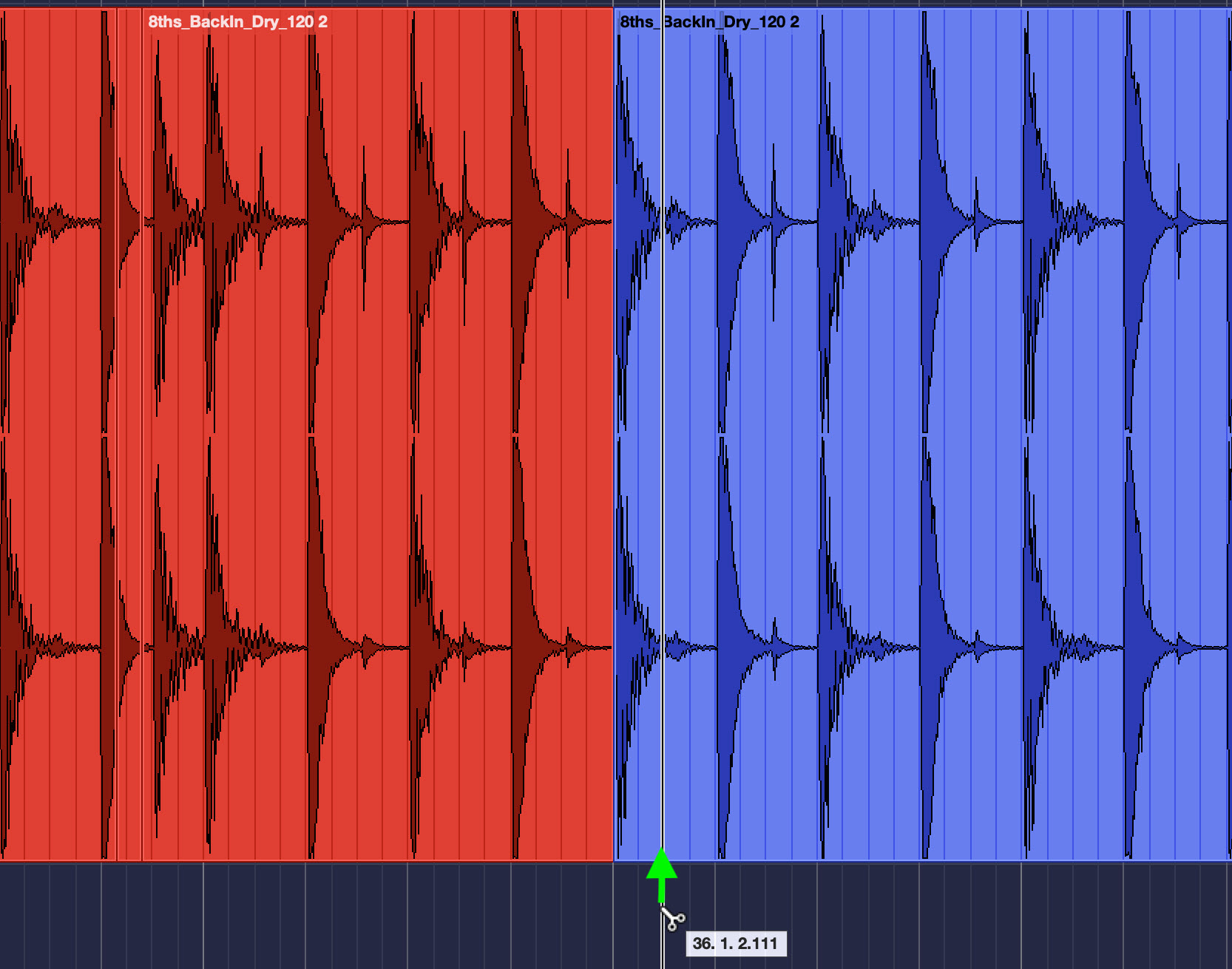

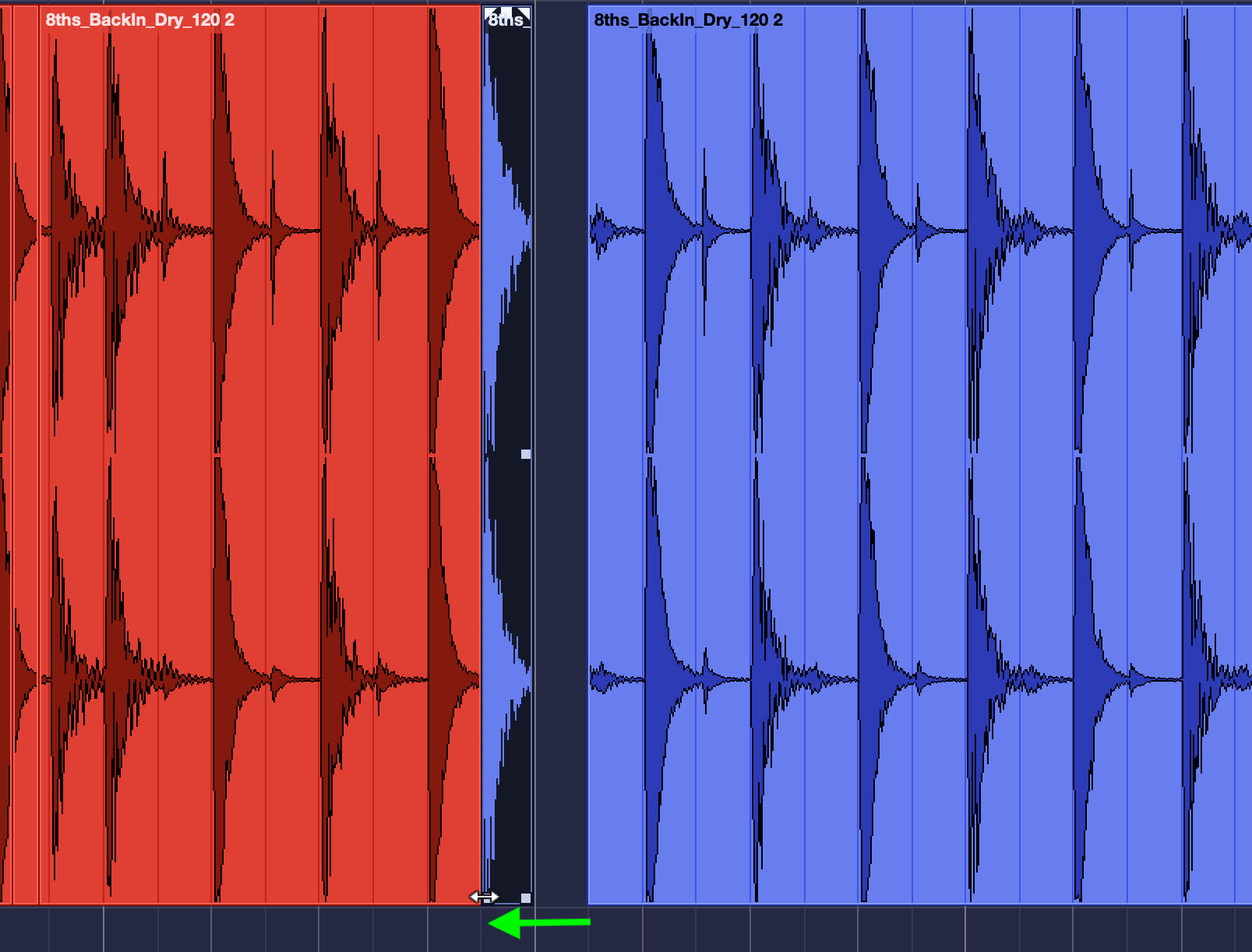

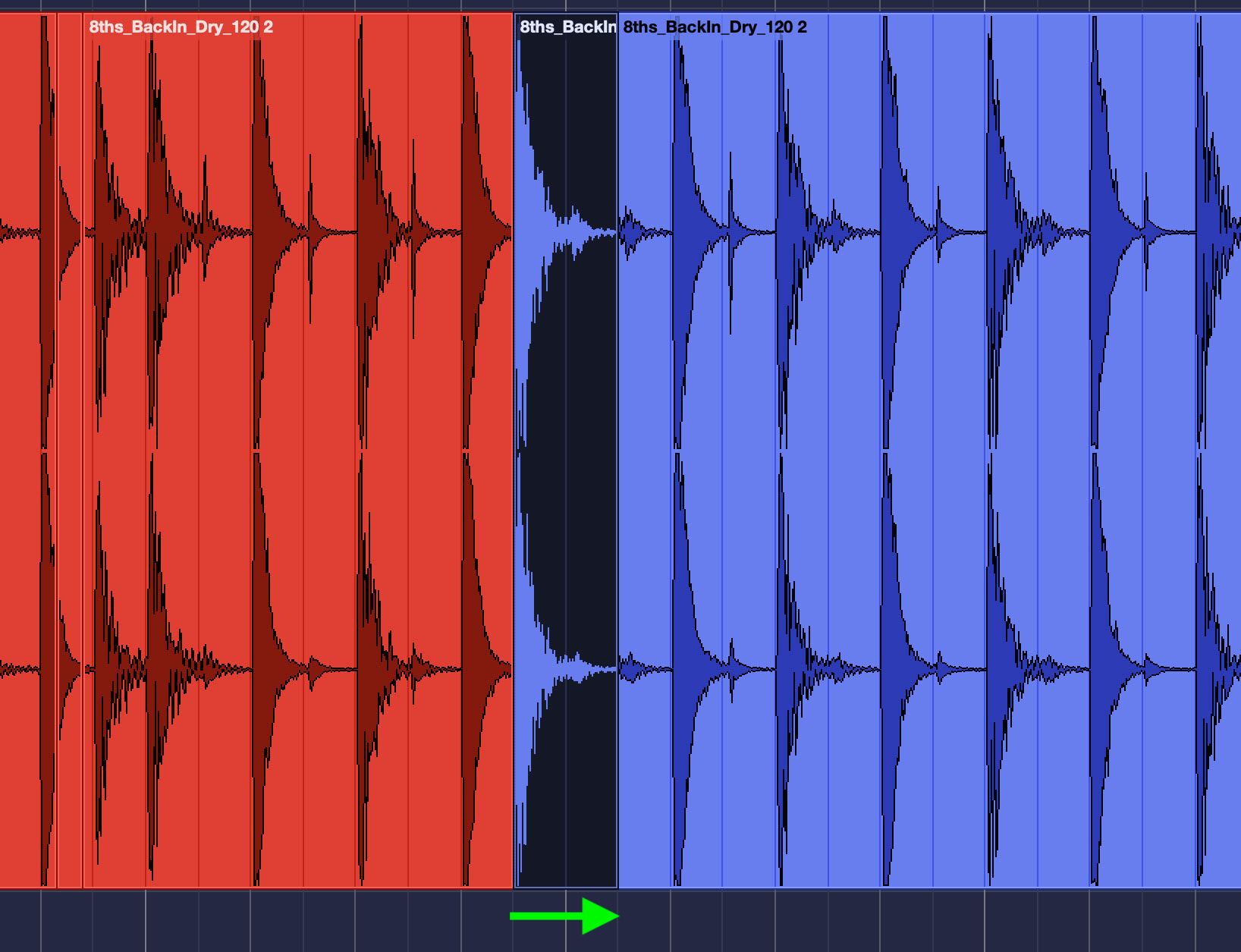

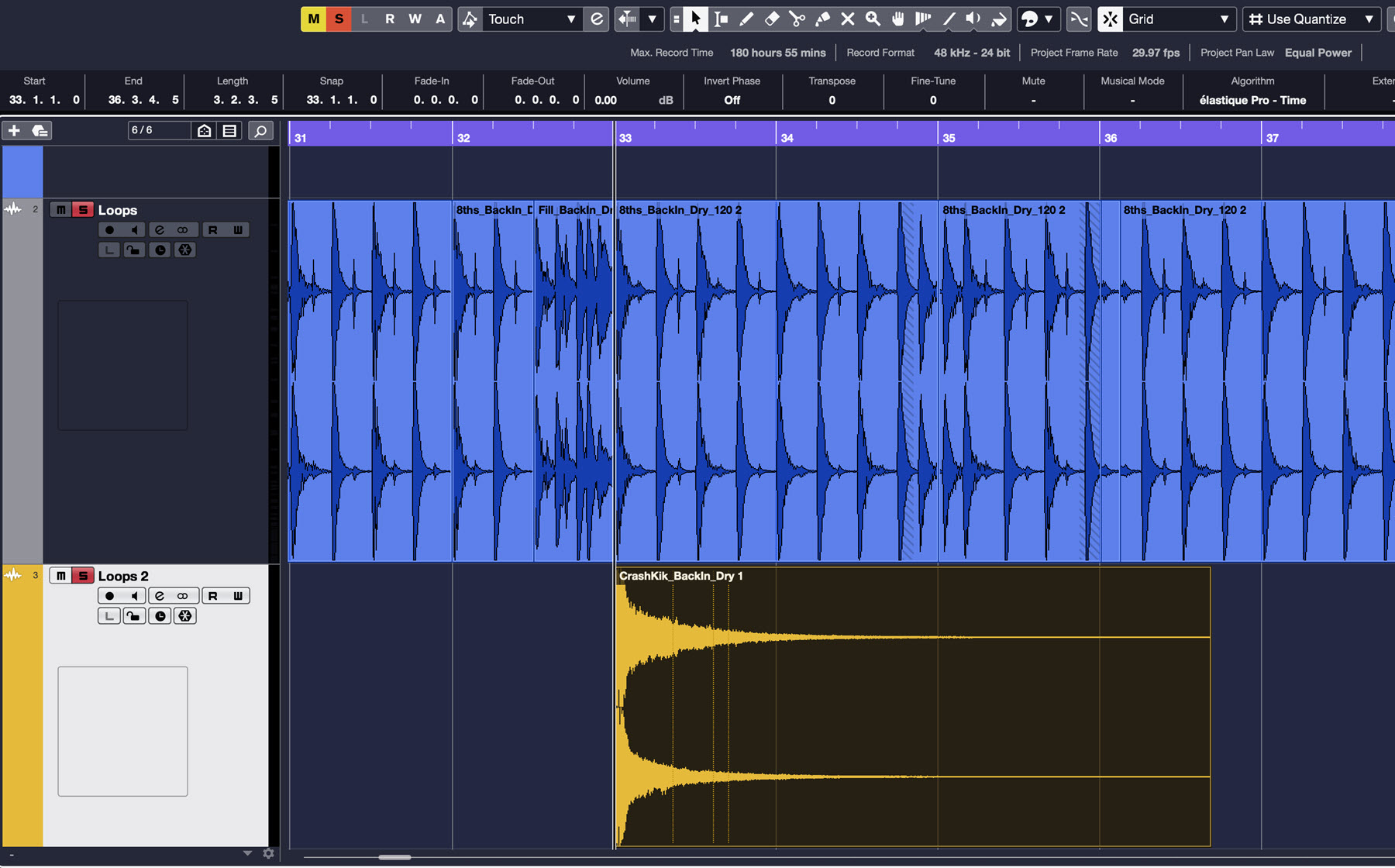

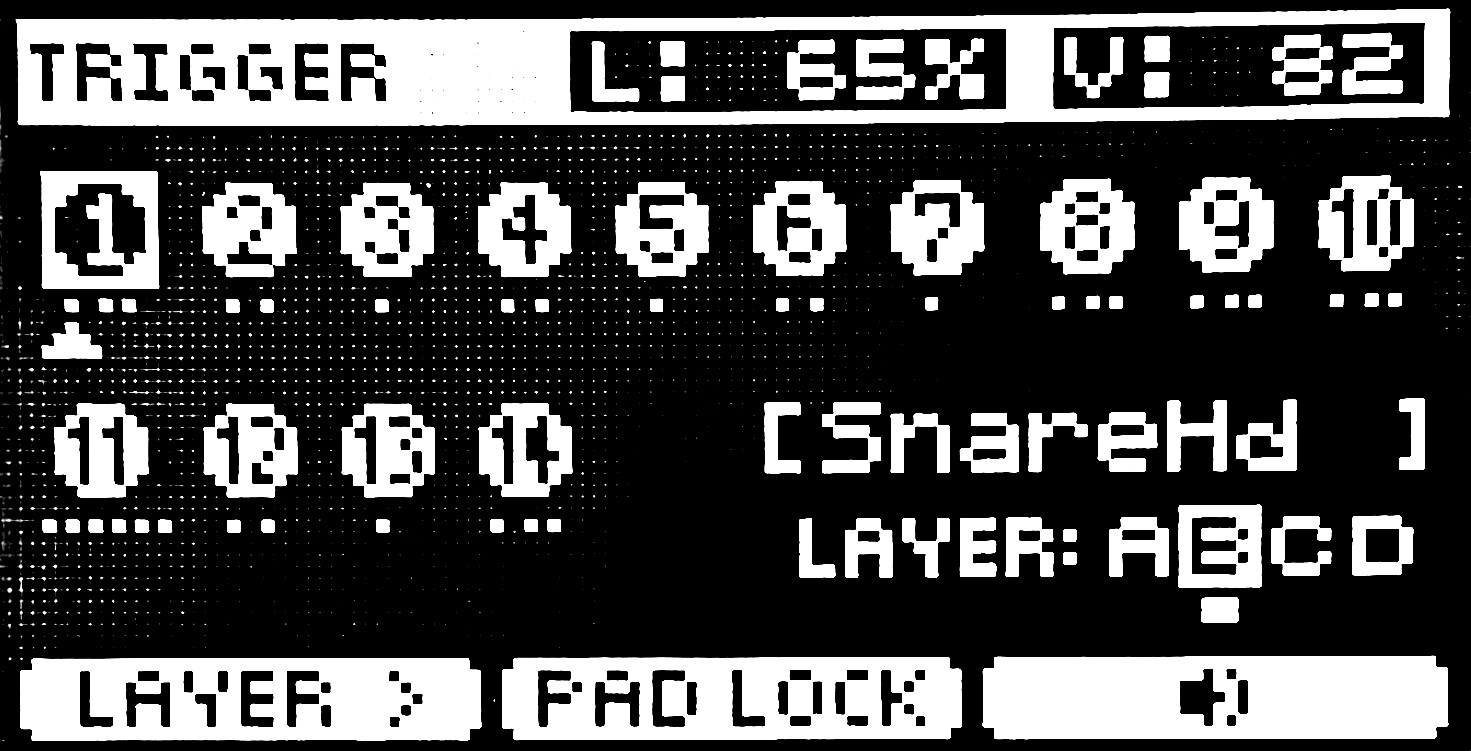

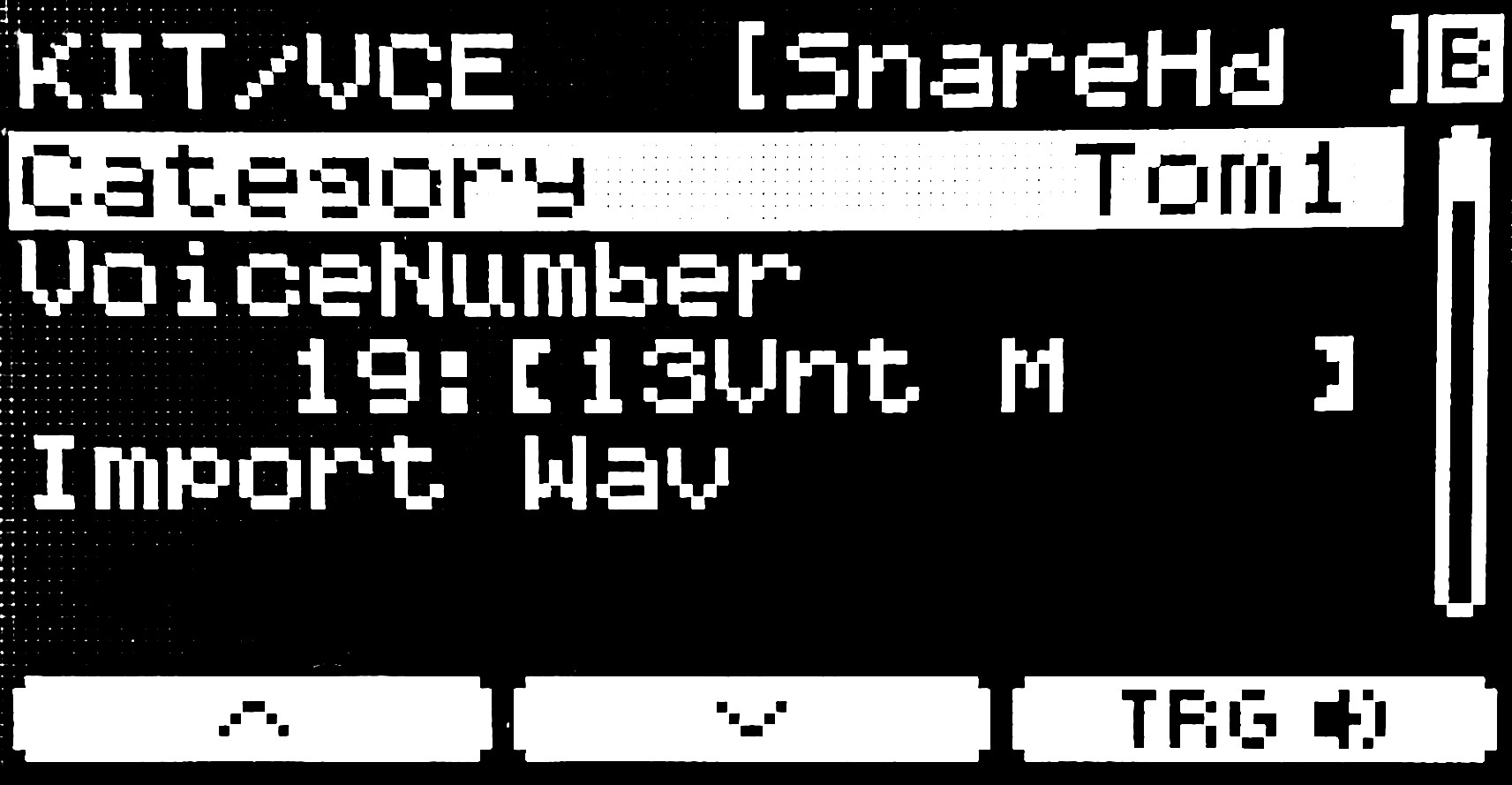

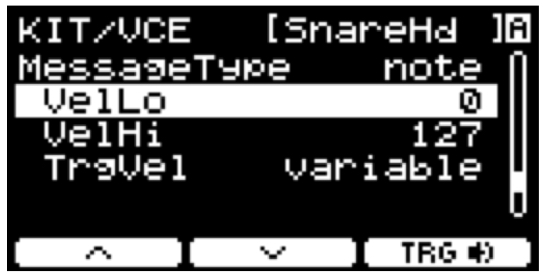

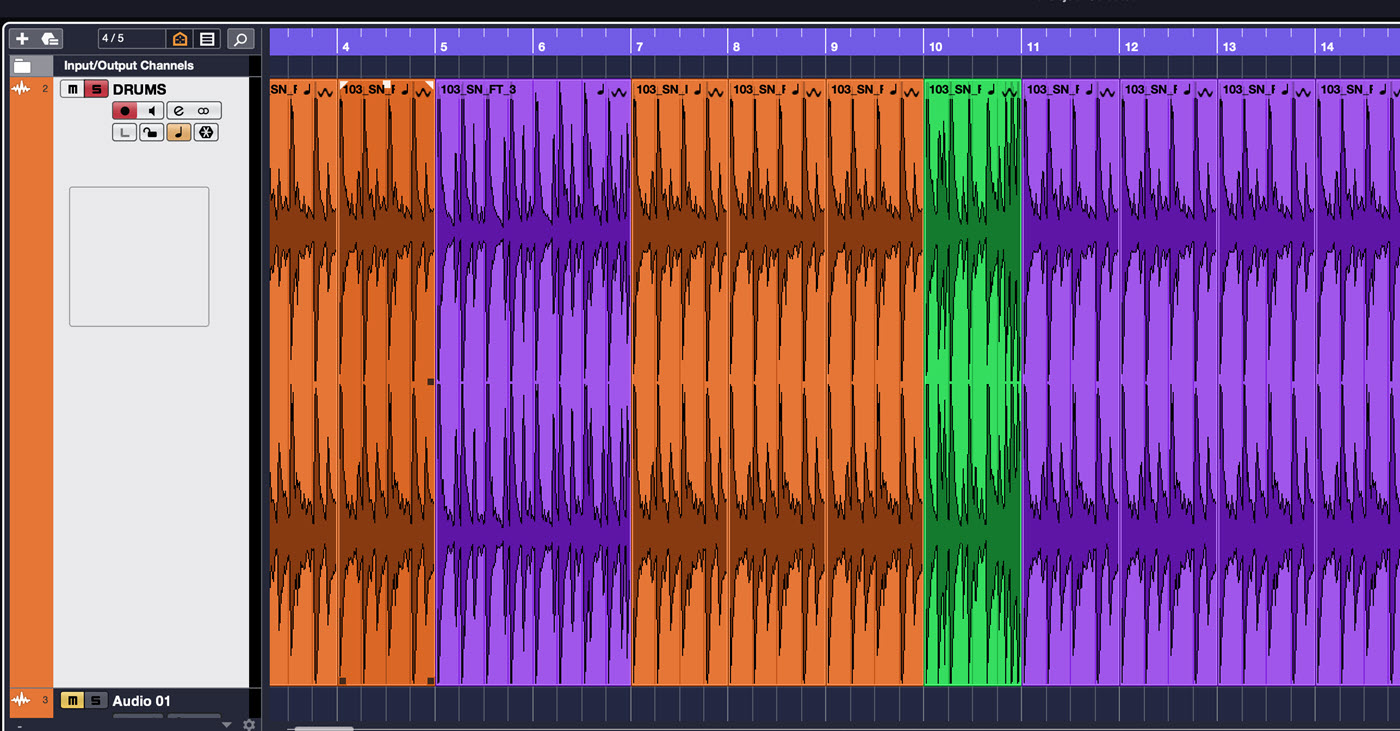

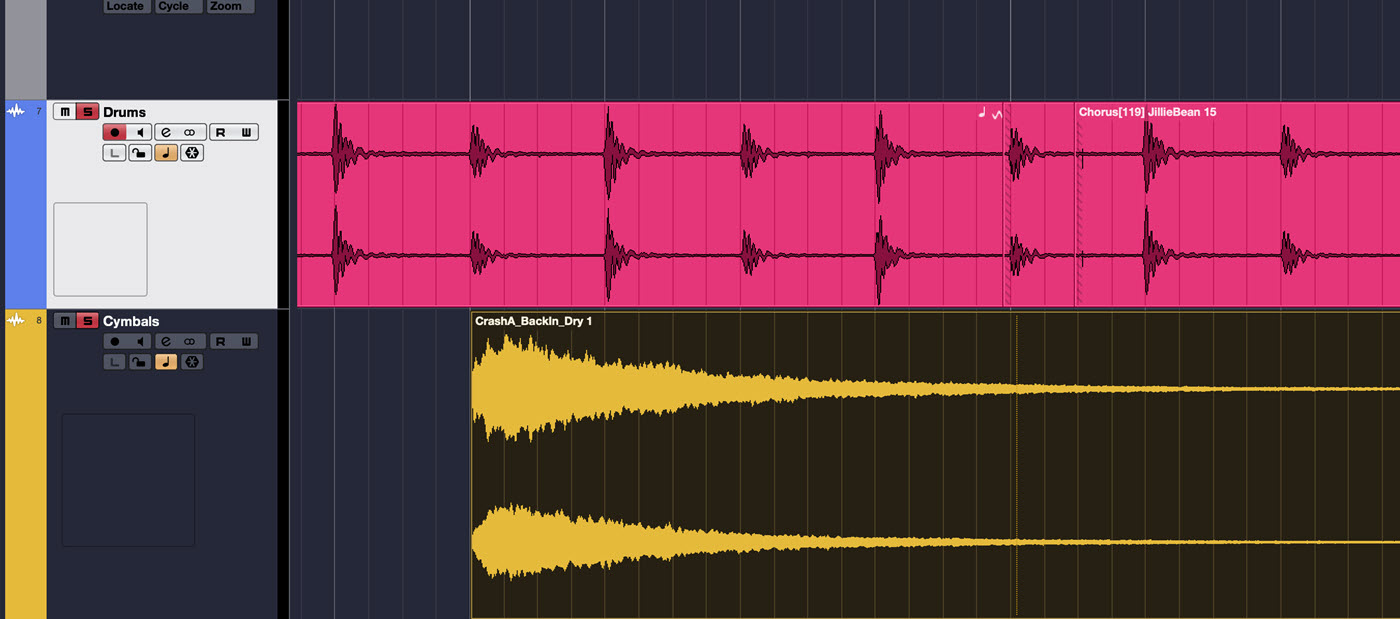

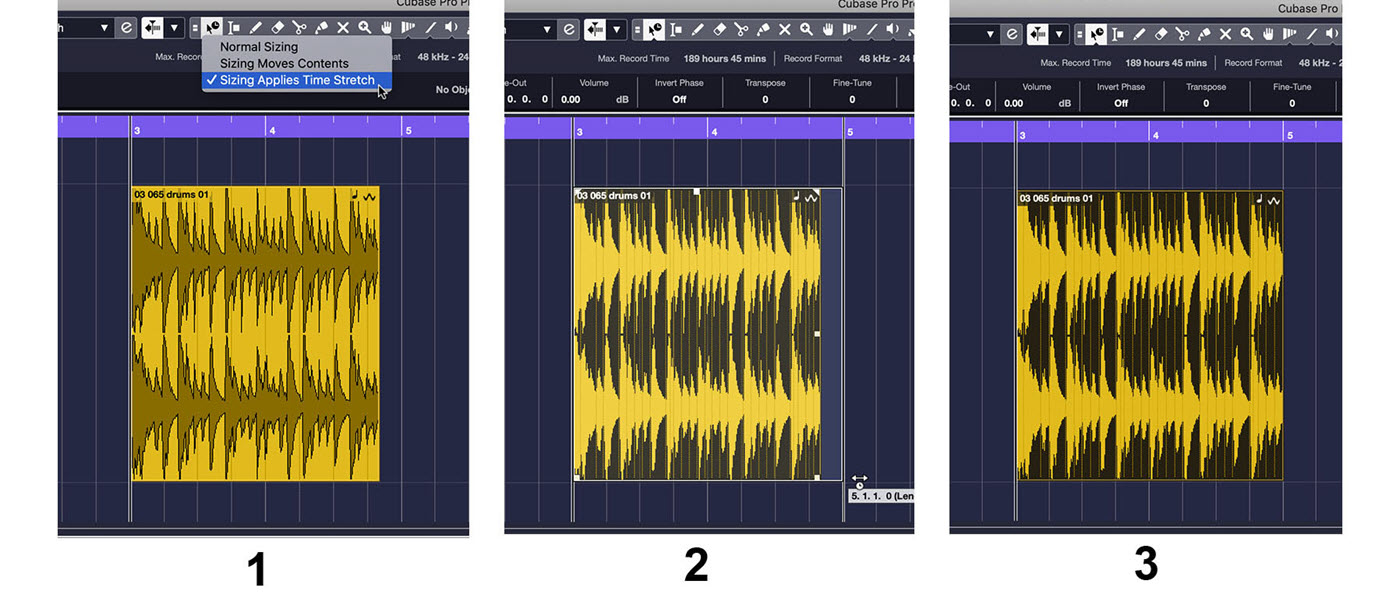

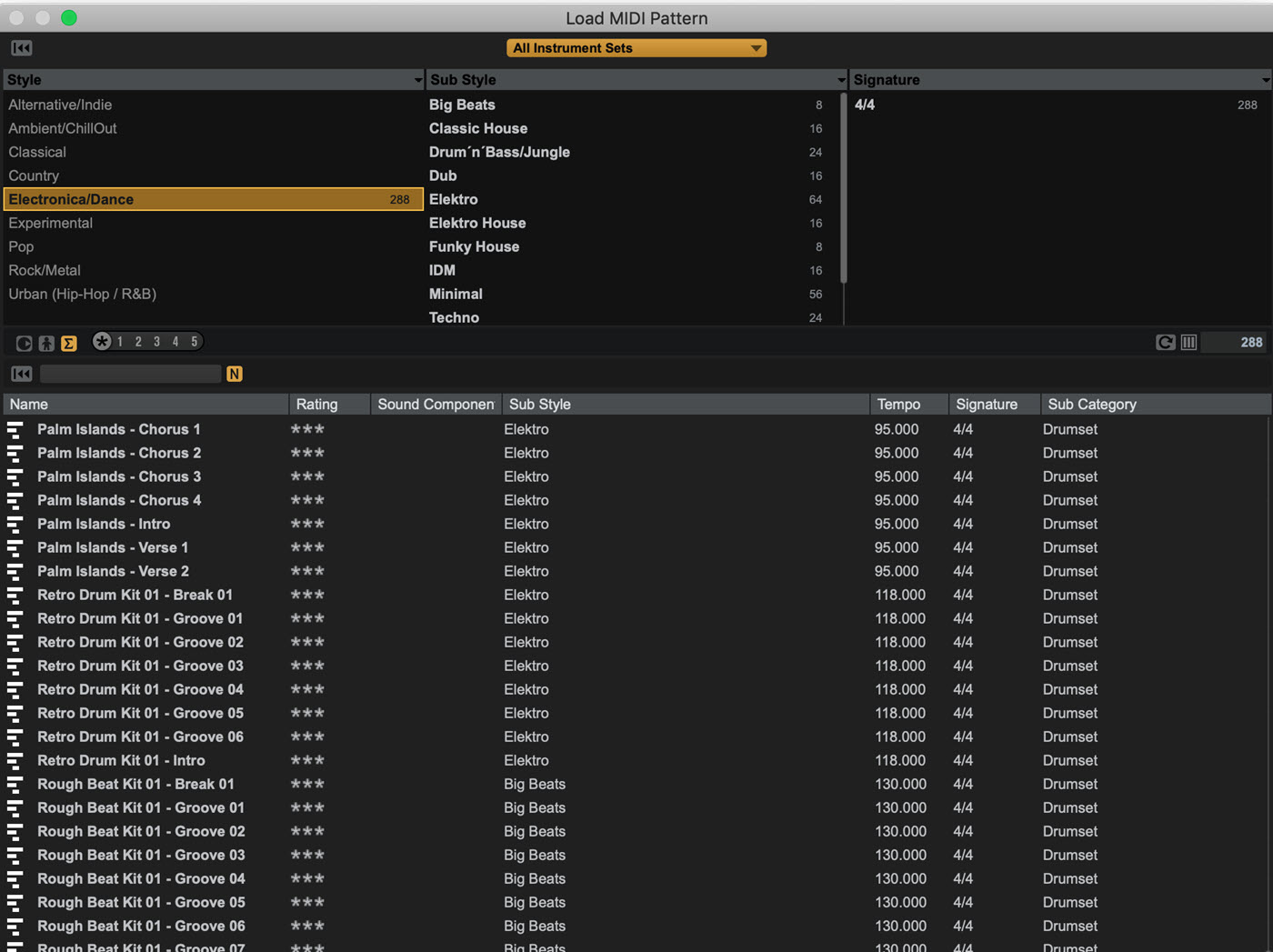

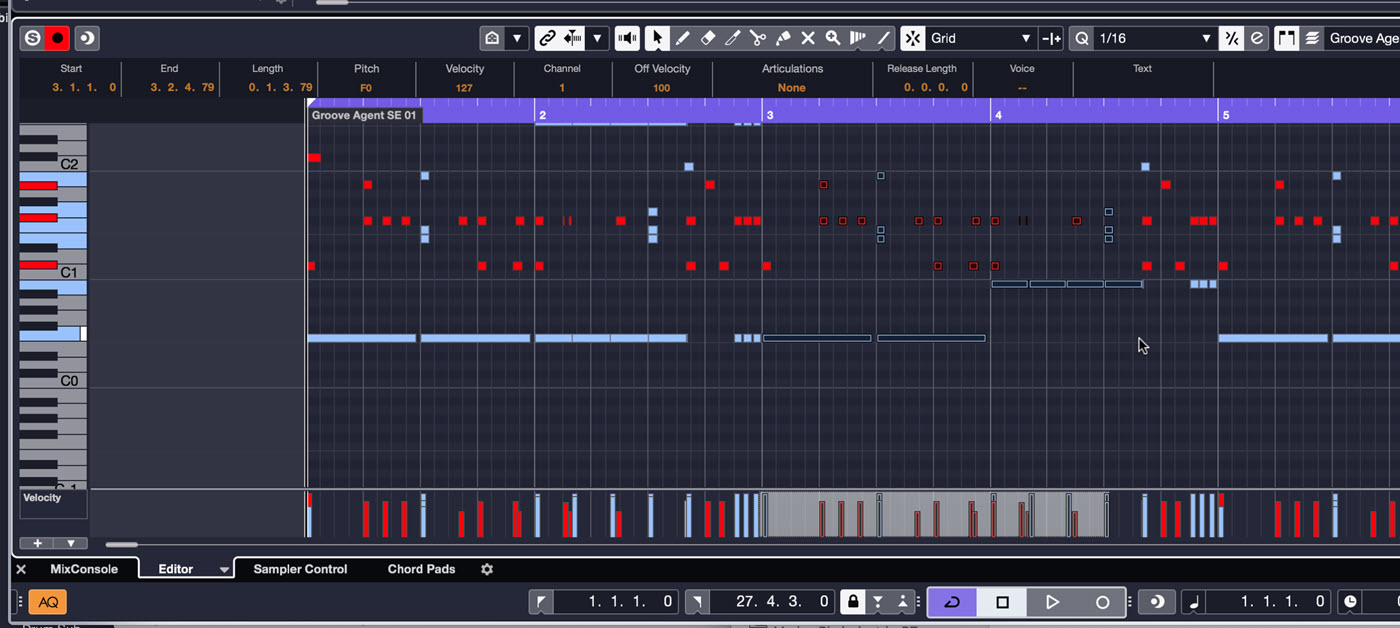

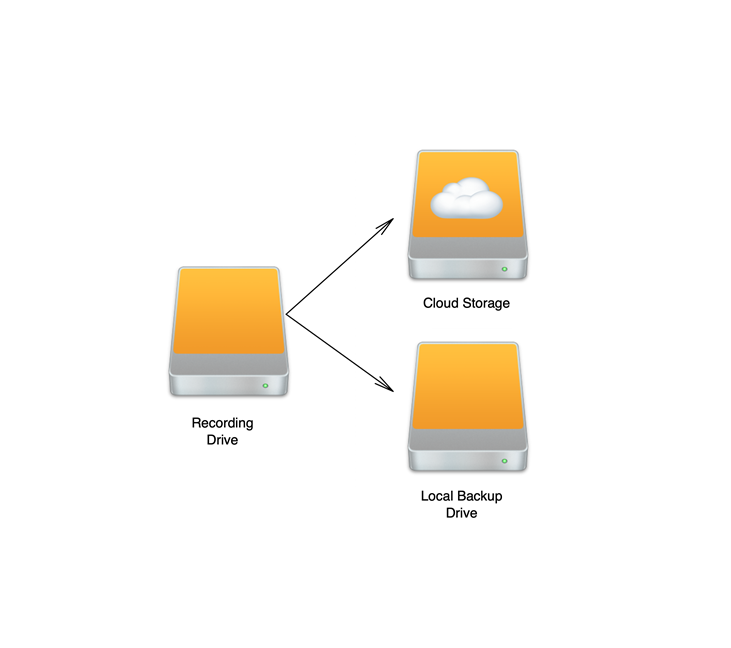

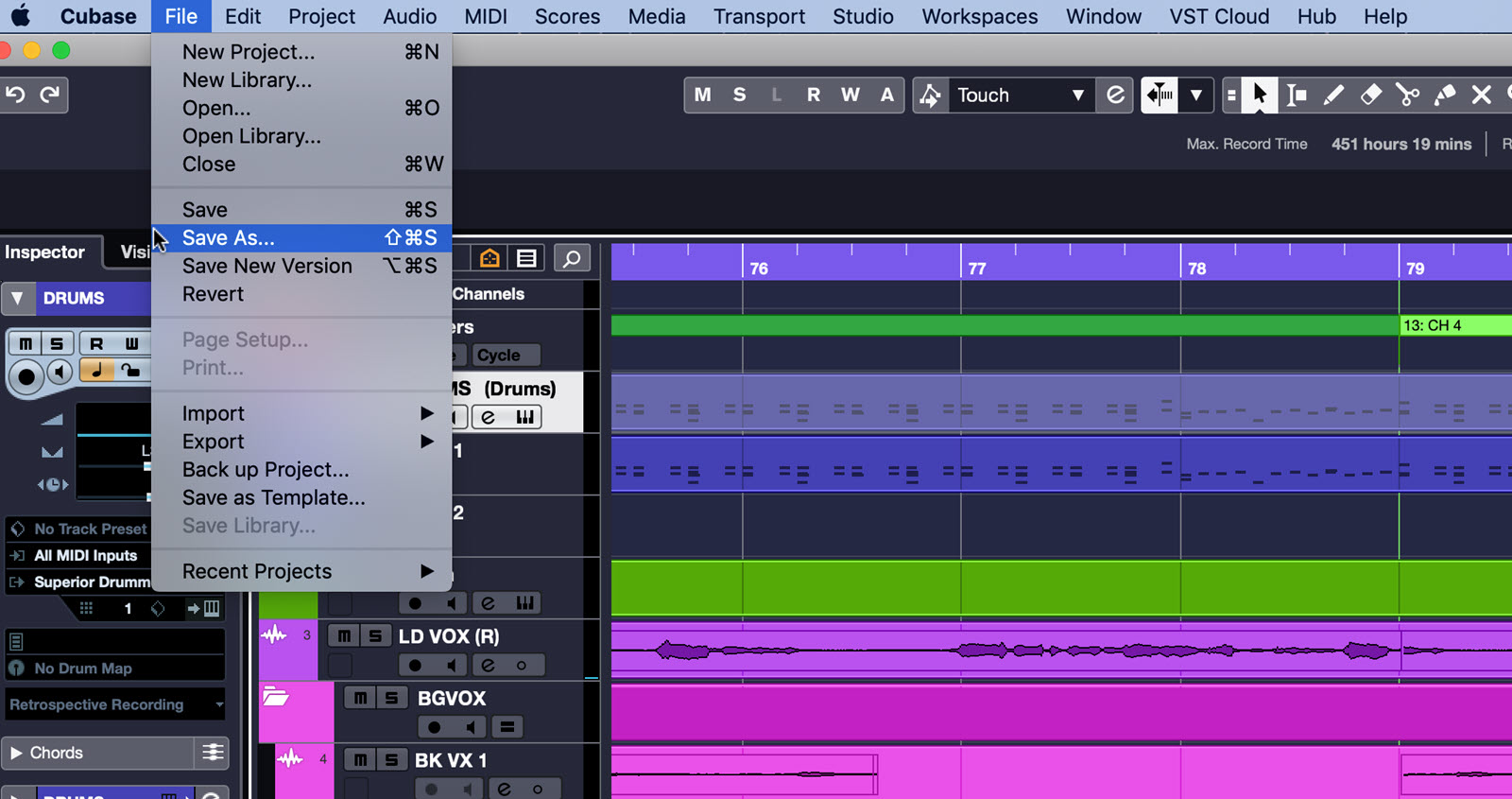

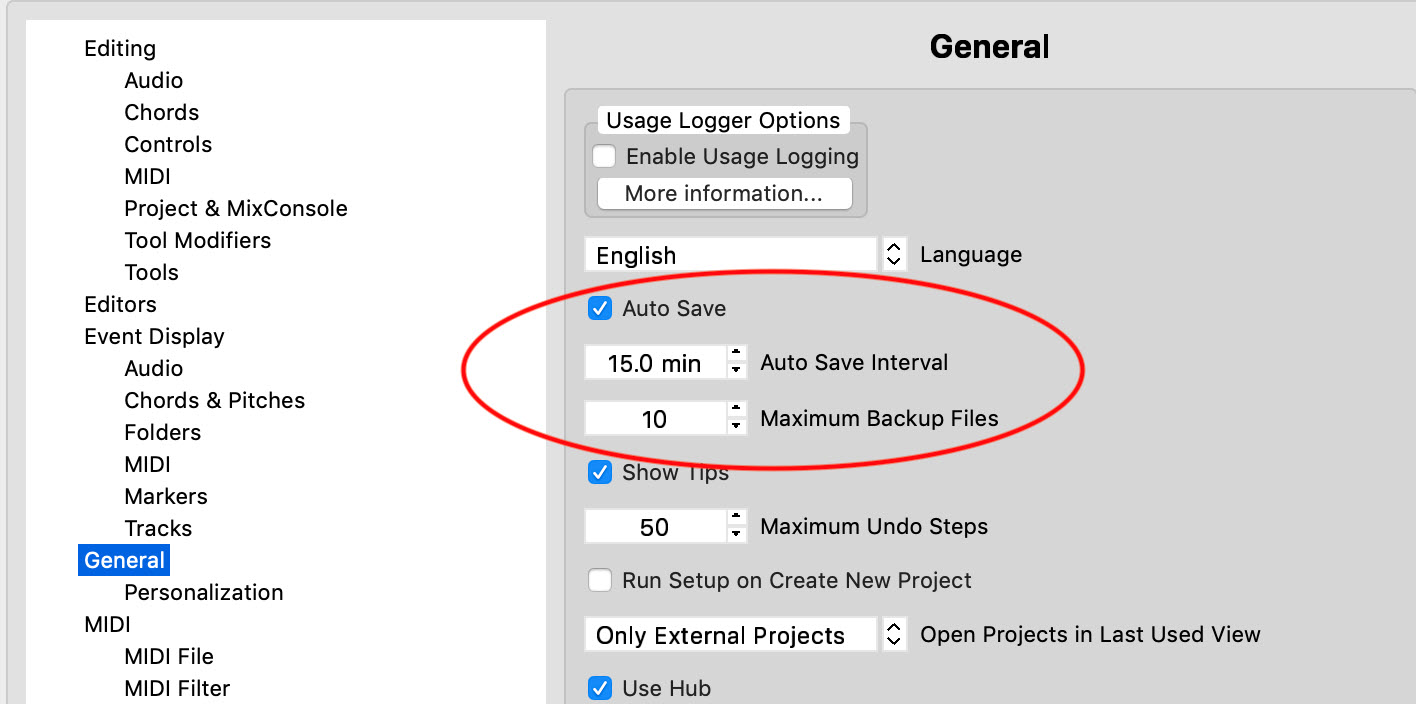

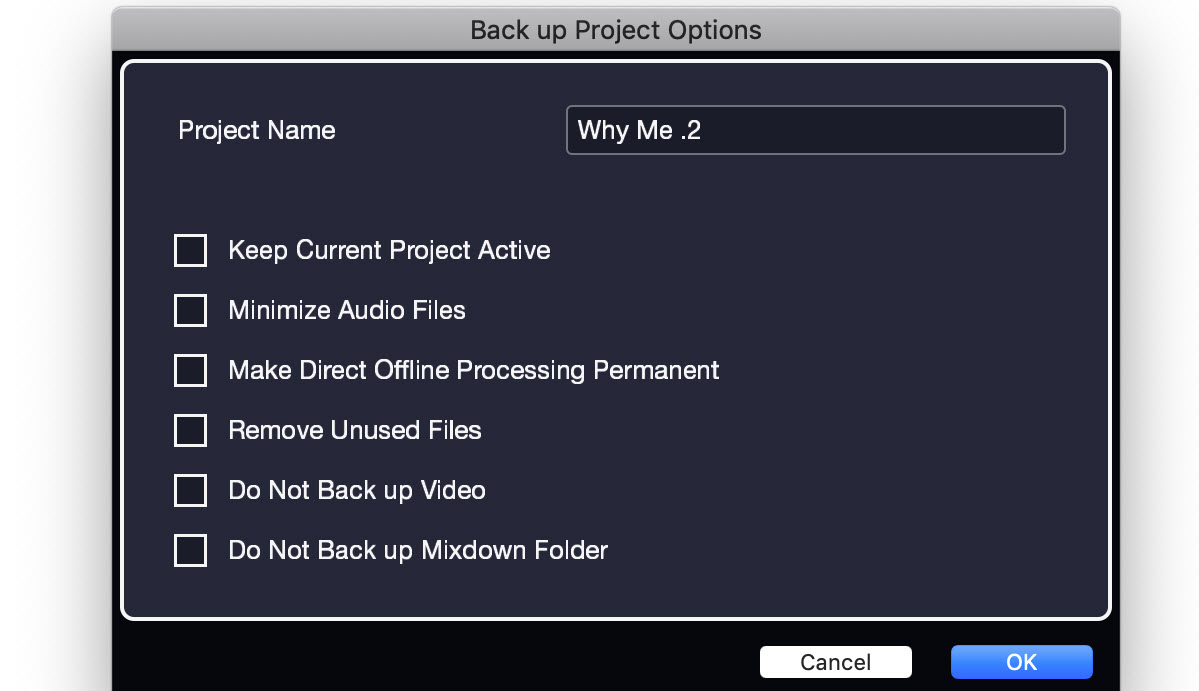

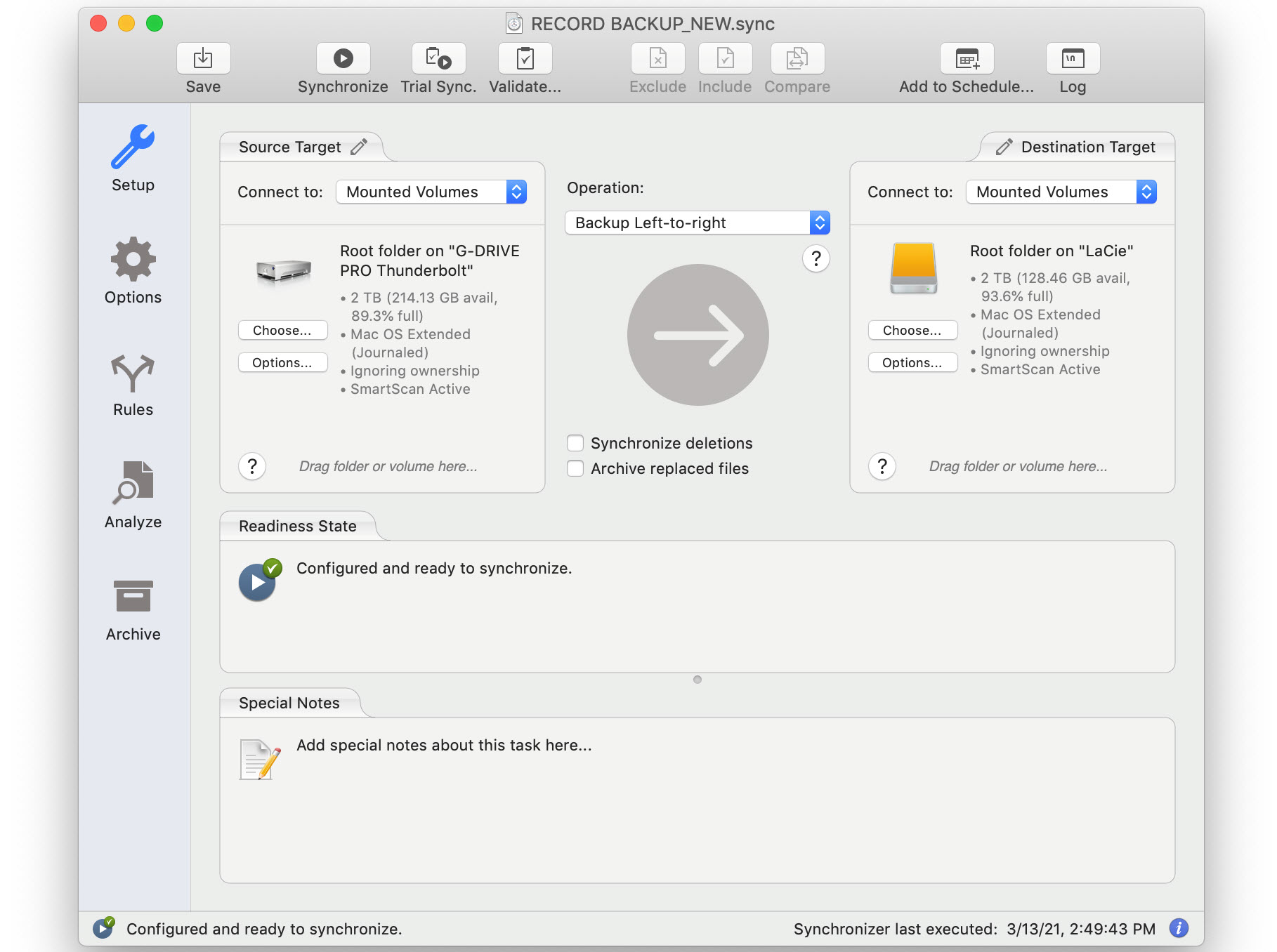

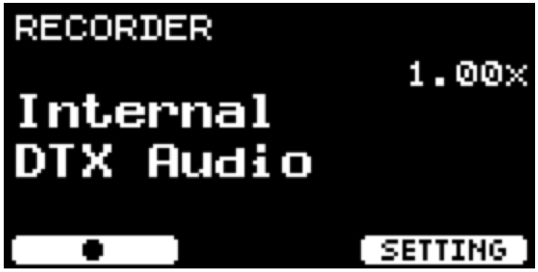

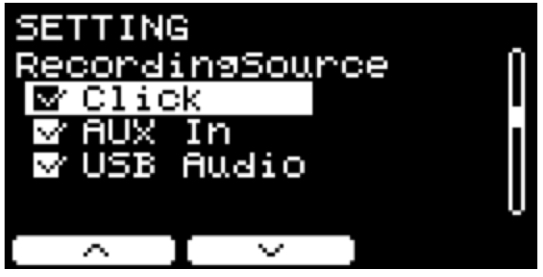

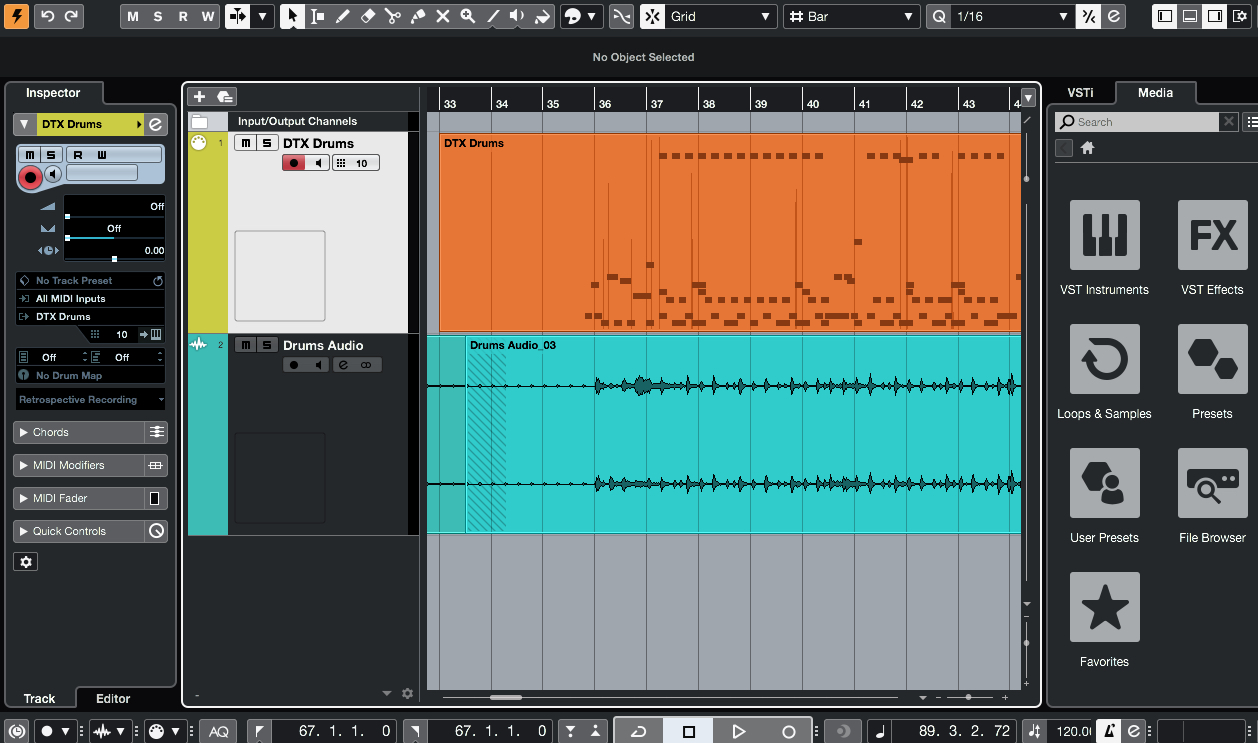

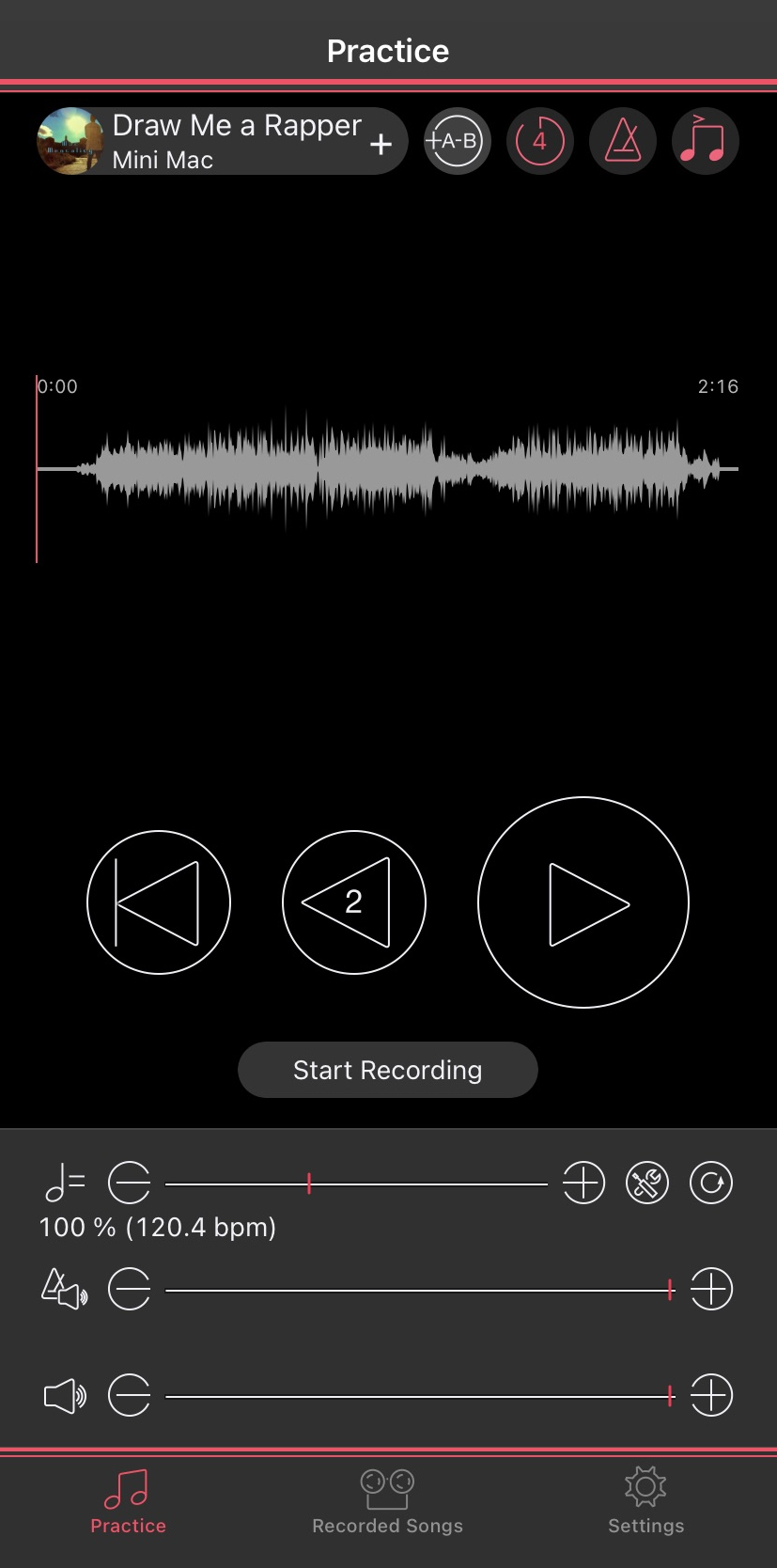

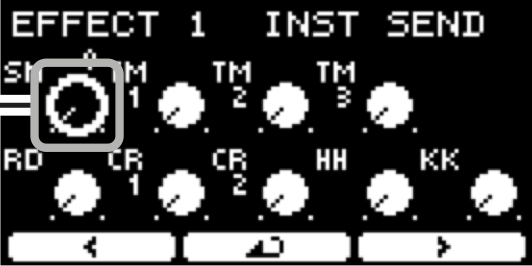

Often, teachers are intrinsically driven to make the favored ensemble from their past the highest quality possible because they have such a clear picture of what they want, they know what success looks like, and they have a strong connection to that particular ensemble. In the fall of 2019, after two years of learning, consulting and writing grants, we had a recording studio in our school! I remember feeling confident that I knew what I didn’t know on the first day of my Digital Audio Production class. Little did I know that I was peering into a doorway of doorways!

In the fall of 2019, after two years of learning, consulting and writing grants, we had a recording studio in our school! I remember feeling confident that I knew what I didn’t know on the first day of my Digital Audio Production class. Little did I know that I was peering into a doorway of doorways! For instance, our marching band went from a three-set to a 60-set show and started participating in the

For instance, our marching band went from a three-set to a 60-set show and started participating in the

An LEA might also address the needs of students arising from the COVID-19 pandemic by using ESSER and GEER funds to implement or expand arts programs,

An LEA might also address the needs of students arising from the COVID-19 pandemic by using ESSER and GEER funds to implement or expand arts programs,  Developing and implementing procedures and systems to improve the preparedness and response efforts of LEAs.

Developing and implementing procedures and systems to improve the preparedness and response efforts of LEAs.

Schaffer and the art teacher now start the recruiting process by visiting 5th grade classes together. “[The art teacher] takes a couple examples of artwork, and I do a quick breakdown on [the process of band].”

Schaffer and the art teacher now start the recruiting process by visiting 5th grade classes together. “[The art teacher] takes a couple examples of artwork, and I do a quick breakdown on [the process of band].” In his first couple of years at his previous position at

In his first couple of years at his previous position at

As they return to “normal,” students may be dealing with grief over lost loved ones and worries about feeling safe. On top of that, they have the evergreen stressors, such as going through puberty, concerns over their appearance or being bullied. Parents are likely feeling anxious, too, with their own worries about employment, physical safety and learning losses for their children.

As they return to “normal,” students may be dealing with grief over lost loved ones and worries about feeling safe. On top of that, they have the evergreen stressors, such as going through puberty, concerns over their appearance or being bullied. Parents are likely feeling anxious, too, with their own worries about employment, physical safety and learning losses for their children. Road Trip!

Road Trip!

After the initial draft was completed, it was clear that one week was not going to be enough time, so I expanded the summer program to two weeks. To help with the next phase of planning, I hired Temple’s music studies coordinator

After the initial draft was completed, it was clear that one week was not going to be enough time, so I expanded the summer program to two weeks. To help with the next phase of planning, I hired Temple’s music studies coordinator  July 2018: After about a year and a half of planning, we arrived at our first program in July 2018. We had 18 students in attendance. About half were from out of town and lived in the Temple dorms, and the rest of the students commuted to and from campus each day. Within the first day, our students formed a strong bond, and the mutual support that they provided one another was beautiful to witness.

July 2018: After about a year and a half of planning, we arrived at our first program in July 2018. We had 18 students in attendance. About half were from out of town and lived in the Temple dorms, and the rest of the students commuted to and from campus each day. Within the first day, our students formed a strong bond, and the mutual support that they provided one another was beautiful to witness. We had no idea how many applications we would get, so we changed our financial model to pay our instructors a variable rate per student rather than provide them with a base stipend. This made it simple for us to scale the program as needed. By the time July rolled around, we were surprised and thrilled to welcome 50 students (a three-fold increase from previous years) tuning in from all across the United States, Canada, Asia and Australia.

We had no idea how many applications we would get, so we changed our financial model to pay our instructors a variable rate per student rather than provide them with a base stipend. This made it simple for us to scale the program as needed. By the time July rolled around, we were surprised and thrilled to welcome 50 students (a three-fold increase from previous years) tuning in from all across the United States, Canada, Asia and Australia. Our 2021 program, which will take place virtually in July, will feature returning instructors

Our 2021 program, which will take place virtually in July, will feature returning instructors

The school year began with band camp, and I hit the ground running by getting to know the students and community members. At the conclusion of the fall semester, the boosters had raised their concession stand money for the year, but we still needed more money. Going around our small town, I met many people who wanted to support the band. I spoke with my administration about launching a fundraising capital campaign to donate for new uniforms. I decided to send

The school year began with band camp, and I hit the ground running by getting to know the students and community members. At the conclusion of the fall semester, the boosters had raised their concession stand money for the year, but we still needed more money. Going around our small town, I met many people who wanted to support the band. I spoke with my administration about launching a fundraising capital campaign to donate for new uniforms. I decided to send  The first year of the grant offered $16,000, 20% of which had to go to professional development. With these funds, I planned to repair all school instruments, so they could be used, and purchase some new instruments to start a supply to offer students. With grand funds in the subsequent years, I would add to the collection of instruments.

The first year of the grant offered $16,000, 20% of which had to go to professional development. With these funds, I planned to repair all school instruments, so they could be used, and purchase some new instruments to start a supply to offer students. With grand funds in the subsequent years, I would add to the collection of instruments. Next school year, the marching band will be back up and running at full capacity with a new show called “Royals of Rock.” We will chronicle a performer’s journey to become a rock legend by learning from the masters like

Next school year, the marching band will be back up and running at full capacity with a new show called “Royals of Rock.” We will chronicle a performer’s journey to become a rock legend by learning from the masters like

Anecdotally, I don’t think they are. In my experience and discussions with teachers in these areas, I think a few other elements are in place. Suburban schools may have lower instances of mobility and chronic absenteeism than a low-income area school. Less movement means that more suburban students go through an entire school system from kindergarten through high school compared to their low-income area counterparts. Wealthier students are also in the classroom more.

Anecdotally, I don’t think they are. In my experience and discussions with teachers in these areas, I think a few other elements are in place. Suburban schools may have lower instances of mobility and chronic absenteeism than a low-income area school. Less movement means that more suburban students go through an entire school system from kindergarten through high school compared to their low-income area counterparts. Wealthier students are also in the classroom more. We can give students the skills to practice if they want to or have the time to practice. Explain your practice techniques and goals during a class. If your students haven’t heard you play, perform for them. I’m happy to say that I’ve had a resurgence in playing my instrument in recent years. I use it almost daily in class for a demonstration or to sit in the band when a student conducts.

We can give students the skills to practice if they want to or have the time to practice. Explain your practice techniques and goals during a class. If your students haven’t heard you play, perform for them. I’m happy to say that I’ve had a resurgence in playing my instrument in recent years. I use it almost daily in class for a demonstration or to sit in the band when a student conducts. When I first started this approach, I noticed a decline in participation in solo and ensemble contests. Participation in our district and state music education conferences remained the same, but we also had few students qualify for this over the past 20 years. However, our group performances increased in both quality and quantity. State festival invitations started coming in. College bands began inviting us to perform on stage with them, and we were even accepted into two national-level performances.

When I first started this approach, I noticed a decline in participation in solo and ensemble contests. Participation in our district and state music education conferences remained the same, but we also had few students qualify for this over the past 20 years. However, our group performances increased in both quality and quantity. State festival invitations started coming in. College bands began inviting us to perform on stage with them, and we were even accepted into two national-level performances.

To address the halftime entertainment dilemma, I went with a Super Bowl™-style halftime show that featured our rock bands. This effort entailed procuring custom-made equipment carts to mobilize all the gear. The following year, we started performing at halftime with our rock/country/pop bands. Because the program was steadily growing, and the students were so excited to perform, we also built a wooden stage outside the stadium for tailgate concerts before the games. Today our football game atmosphere reflects a school-wide festival with pregame concerts, barbecues as well as cheerleader and dance team performances.

To address the halftime entertainment dilemma, I went with a Super Bowl™-style halftime show that featured our rock bands. This effort entailed procuring custom-made equipment carts to mobilize all the gear. The following year, we started performing at halftime with our rock/country/pop bands. Because the program was steadily growing, and the students were so excited to perform, we also built a wooden stage outside the stadium for tailgate concerts before the games. Today our football game atmosphere reflects a school-wide festival with pregame concerts, barbecues as well as cheerleader and dance team performances. The new focus of the music program has transformed the campus with music becoming a part of everyday school life. The music room was reconfigured to be more student-centric. Instead of walking in and seeing rows of chairs, the room is set up like a live music studio with all the equipment hooked up and ready to provide an atmosphere where students can walk in and begin playing. Seating is set up in a circular fashion where everyone can look at each other and efficiently communicate during rehearsals and easily walk between stations. The idea is that everyone’s part is just as important as the other, and for music to come alive, everyone needs to do their part.

The new focus of the music program has transformed the campus with music becoming a part of everyday school life. The music room was reconfigured to be more student-centric. Instead of walking in and seeing rows of chairs, the room is set up like a live music studio with all the equipment hooked up and ready to provide an atmosphere where students can walk in and begin playing. Seating is set up in a circular fashion where everyone can look at each other and efficiently communicate during rehearsals and easily walk between stations. The idea is that everyone’s part is just as important as the other, and for music to come alive, everyone needs to do their part. Music students also host “Music-On-The-Deck,” an open-mic performance on the outdoor stage during lunchtime on Fridays during which anyone on campus may perform. Students bring blankets and picnic while listening to their peers play and sing.

Music students also host “Music-On-The-Deck,” an open-mic performance on the outdoor stage during lunchtime on Fridays during which anyone on campus may perform. Students bring blankets and picnic while listening to their peers play and sing.

Located in metropolitan Atlanta, the

Located in metropolitan Atlanta, the  For instrumental music, we provided band and orchestra instruments for programs with the greatest need. The school district provides funding yearly for larger and more costly instruments and equipment, including low-brass instruments, double reeds, low saxophones, percussion, cellos and basses. Other instruments like violins, violas, flutes, clarinets, trumpets and alto saxophones are usually provided by the students themselves

For instrumental music, we provided band and orchestra instruments for programs with the greatest need. The school district provides funding yearly for larger and more costly instruments and equipment, including low-brass instruments, double reeds, low saxophones, percussion, cellos and basses. Other instruments like violins, violas, flutes, clarinets, trumpets and alto saxophones are usually provided by the students themselves

It all started when a group of students approached me to ask if they could use the choir room for what would eventually become the afterschool Musician’s Club. In the process of agreement, I became the sponsor of this fledgling group of garage band musicians. Each Thursday, we met for an hour after school. These students were passionate about the music industry.

It all started when a group of students approached me to ask if they could use the choir room for what would eventually become the afterschool Musician’s Club. In the process of agreement, I became the sponsor of this fledgling group of garage band musicians. Each Thursday, we met for an hour after school. These students were passionate about the music industry. Subsequently, I invited

Subsequently, I invited  Music business education is adaptable to any demographic profile and molds to meet existing needs in a school or district. In addition, music business education is cross-curricular and also addresses the skillsets taught in the STEM pathway. Finally, remote learning is probably here to stay — at least in part. Music business education works on a digital platform just as easily as in person. Unlike a traditional music class where directors have scrambled to create a way to teach and assess a performance-based class virtually, music business is interactive and frees the teacher to design lessons that can be assimilated through a variety of mediums.

Music business education is adaptable to any demographic profile and molds to meet existing needs in a school or district. In addition, music business education is cross-curricular and also addresses the skillsets taught in the STEM pathway. Finally, remote learning is probably here to stay — at least in part. Music business education works on a digital platform just as easily as in person. Unlike a traditional music class where directors have scrambled to create a way to teach and assess a performance-based class virtually, music business is interactive and frees the teacher to design lessons that can be assimilated through a variety of mediums.

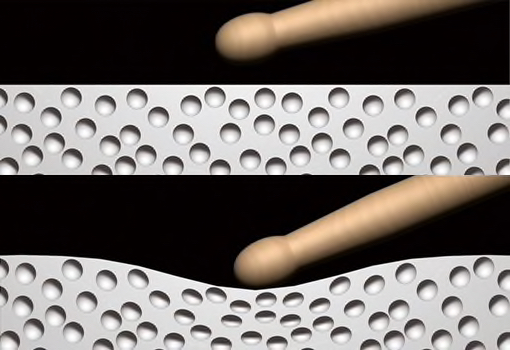

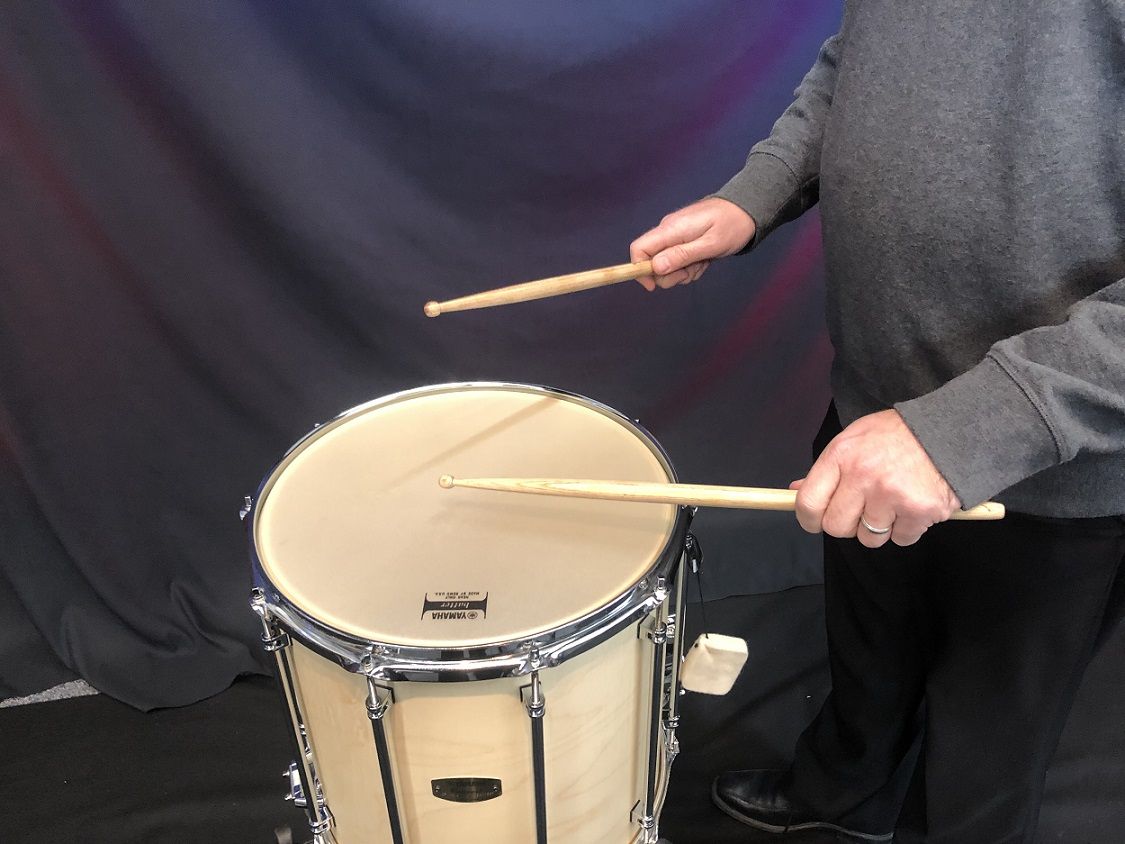

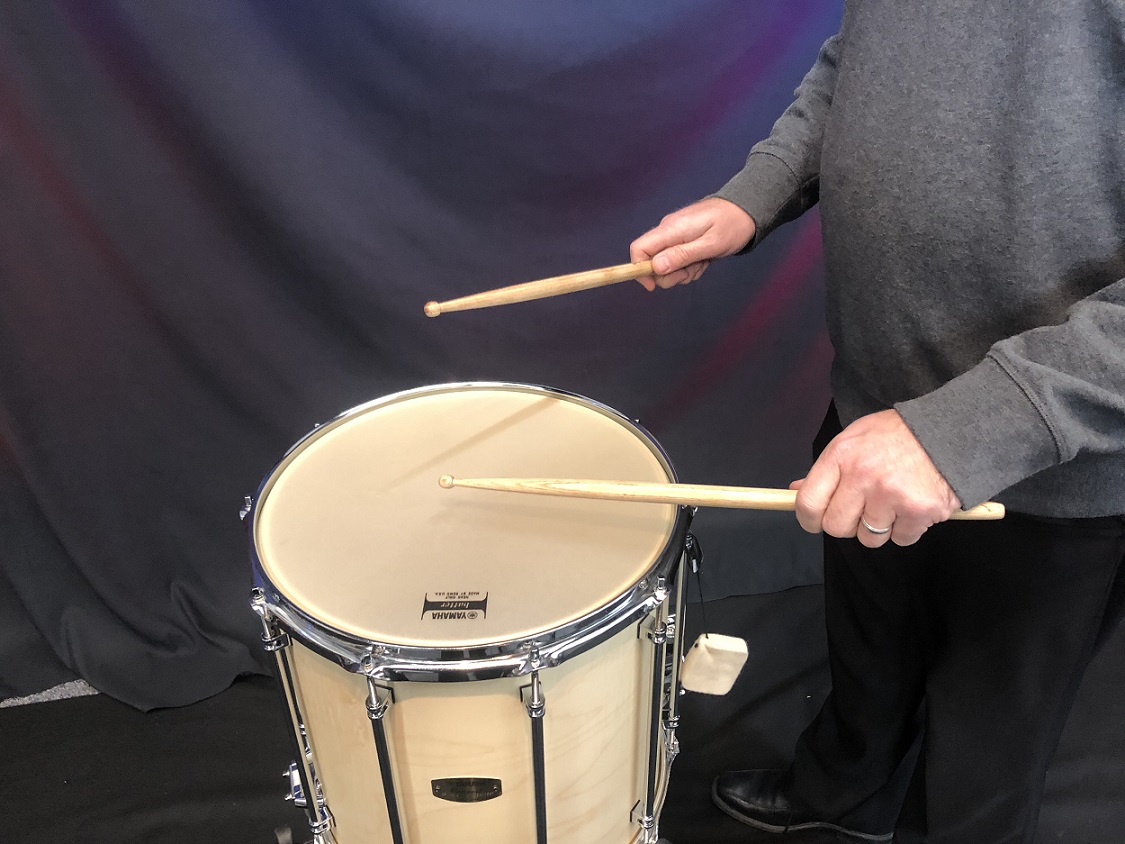

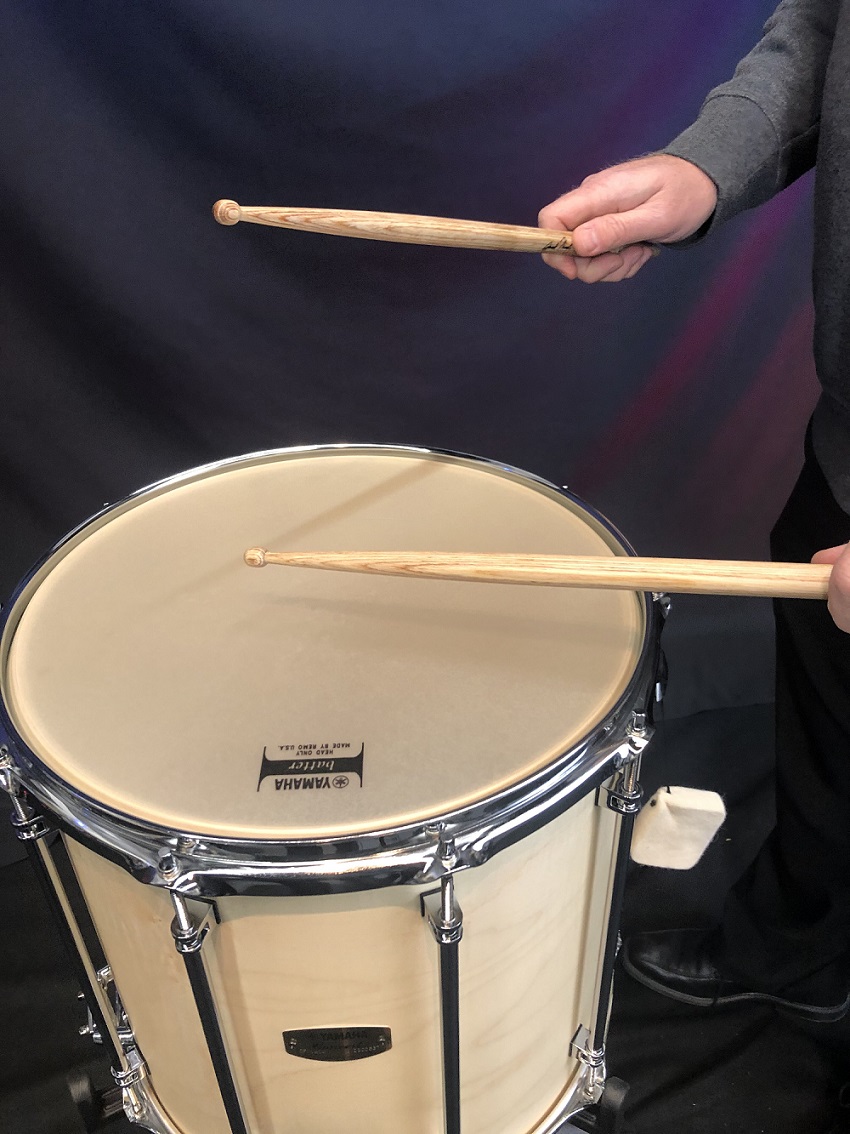

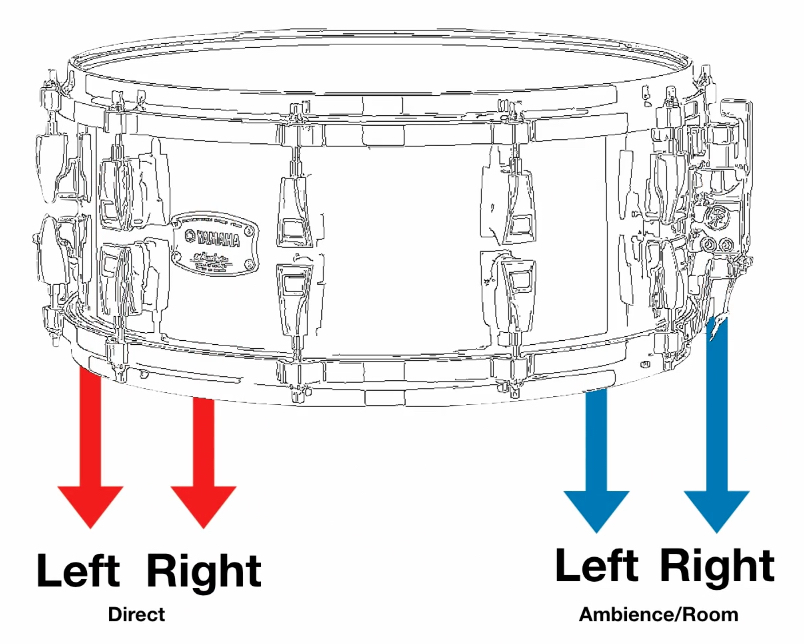

One of the things that makes the snare drum and snare drummers special is the capacity and responsibility to lead. Whether laying down a powerful backbeat on drum set, executing a delicate passage in orchestra or cleaning a showstopping feature in drumline, the snare drum acts as the “nucleus” of percussion — the center from which everything else derives.

One of the things that makes the snare drum and snare drummers special is the capacity and responsibility to lead. Whether laying down a powerful backbeat on drum set, executing a delicate passage in orchestra or cleaning a showstopping feature in drumline, the snare drum acts as the “nucleus” of percussion — the center from which everything else derives.

As the parade floats passed by my family, I could hear something rumbling and sensed a quickening of energy from just over the hill to our left. It was the high school marching band! As the students emerged before us, the crisp, throaty timbre of early 1980s marching snare drums resonated to a fever pitch throughout my entire body. I’ve been chasing this feeling ever since.

As the parade floats passed by my family, I could hear something rumbling and sensed a quickening of energy from just over the hill to our left. It was the high school marching band! As the students emerged before us, the crisp, throaty timbre of early 1980s marching snare drums resonated to a fever pitch throughout my entire body. I’ve been chasing this feeling ever since.

Let’s start with the little details — the most basic ways to build a positive relationship with your music students.

Let’s start with the little details — the most basic ways to build a positive relationship with your music students. Provide ways for students to touch base outside of the classroom. This might be holding regular office hours and encouraging drop-ins, or you could have a classroom “Talk to Me” box, where students can drop in their thoughts.

Provide ways for students to touch base outside of the classroom. This might be holding regular office hours and encouraging drop-ins, or you could have a classroom “Talk to Me” box, where students can drop in their thoughts.