Starting your career as a music educator is an exciting time! Who better to offer some words of wisdom than the Yamaha “40 Under 40” music educators for 2023?

Below are 122 tips that will help you navigate your first year of teaching.

1. Find an encouraging and wise mentor — this can be life-changing! A mentor will keep you abreast of current teaching trends while also helping you keep your head above water with all the other ‘minutia’ required in education. You are so valuable, and students need YOU! To the world you may be one person, but you truly have an opportunity to change the world, one student at a time.

2. Whenever you can, go watch a successful teacher. This teacher doesn’t have to be another music educator. Take your planning period and go observe the teacher of the year within your building. Watch the conductors at your Region Event and All-State and glean every rehearsal technique you can.

3. Be vulnerable – video tape yourself teaching. Watch it and reflect and, if you can, share it with your mentor to receive feedback.

The Yamaha Educator Newsletter: Join to receive a round-up of our latest articles and programs!

1. Be organized and create a plan. This will help you stay on top of all the tasks that come with being a music educator.

2. Get to know your students and their interests. This will help you create lesson plans that are engaging and relevant to them.

3. Connect with other music educators in your area. This is a great way to get advice, ideas and support from those who have been in your shoes before.

1. It is not always about what you like or even want. Example: Just because you may really like a song, it may not be a good fit for your group at that particular time. Not every kid who comes into the band room is going to be a band director one day. You will have students come to you with a variety of different interests, levels, backgrounds and needs. Make sure that the decisions you make are what is best for the band and the program as a whole. Every school, every program and every situation is a little different.

2. Know the repertoire for the level you are teaching. Picking the correct repertoire can be the make or break for so many things for the program and band member retention. If the band learned fundamental musical concepts playing the repertoire, and the band had fun and continues to play at the next level — then you did your job. Plaques, trophies and awards are not the reason we do what we do, period.

3. Don’t be afraid to reach out to other band directors. As band directors, we are often on an island. Most schools have one band director (unlike the English and Math departments where there are multiple other teachers teaching the same content). There will likely be no department head (or if there is, it is not uncommon for them to have a totally different specialty.)

Tyler Wigglesworth

Tyler Wigglesworth

Choir Director, Performing Arts Academy Coordinator, Vocal Music Director

West Covina High School

West Covina, California

1. Get to know the community, as well as the individual students who you serve. They are each unique humans who bring so much to the table in the music-making process, and every community and student is unique.

2. Always look to foster relationships with your colleagues as well as other music/performing arts professionals. Not only does this open up pathways for potential collaborations, but it is also a great way to demonstrate respect, inclusion, and love for others to our students.

3. Cut yourself some slack. “Rome was not built in a day,” and your music program won’t be either. Have an ambitious and hopeful vision for the current year, the upcoming year, the next five years, even the next 10 years. Having a vision for your program, and a dedication to an excellent execution of that vision, will help you begin to develop and shape your program into something really wonderful. Take on one thing at a time but do it excellently, and it will grow!

1. Become the BEST musician you can possibly be. Listen to great music, STUDY your music and perform as much as possible.

2. Focus on communication. There is no such thing as overcommunication. Most people only get to know you through email, so make the craft of writing a priority.

3. Take time for yourself. This profession is hard, but worthwhile. Make sure you are taking every opportunity to lengthen the sustainability of your career.

1. Listen to your students, and respond to them like humans, not children who must obey! If you bring respect to the table, the students will follow suit.

2. Admit when you don’t know something, and model looking it up!

3. Build relationships first through structure, routine and consistency.

1. Go above and beyond. Being a music educator to high schoolers means that you not only need to be a strong musician/conductor/producer but you must also be emotionally available for your students. A level of mutual trust must be built.

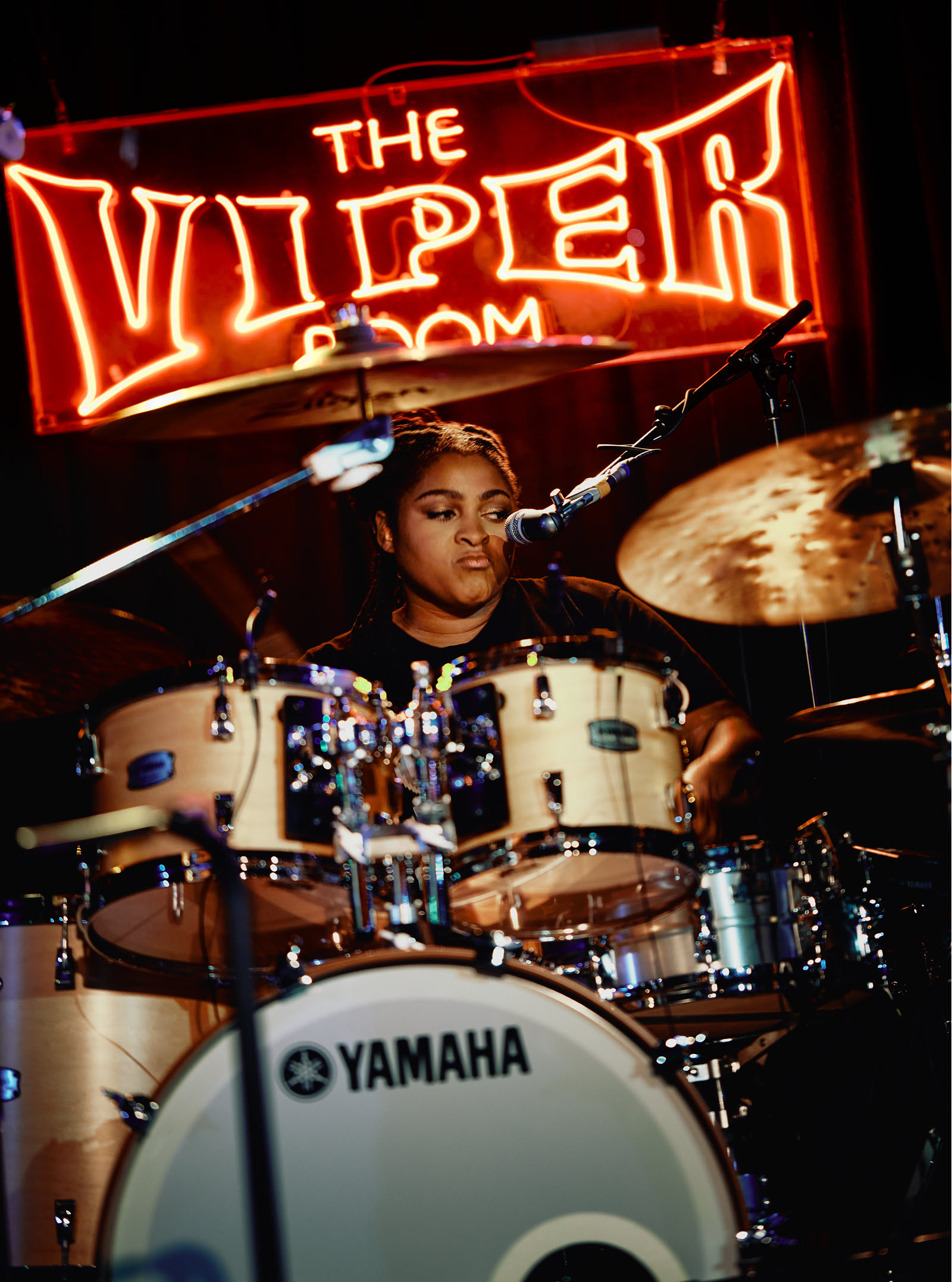

2. If you are an instrumentalist or vocalist, continue to perform and develop your own craft. Find ways to still be on stage and hone your own performance rituals that you can pass on to your students. If you are asking your students to perform, you also need to remain a performing artist.

3. No matter your age, stay up to date with all current music from every genre.

1. Perseverance: This has been my word since I started teaching. I kept hearing that “it gets better,” and I finally figured out that we, as educators, get better! I remember going home crying during my first year and feeling exhausted from all the extra hours and weekends I would put in. But I always remembered that it took my teacher six years of not giving up before I finally joined her mariachi class, and I cannot express how grateful I am that she persevered because I would not be where I am today if she had given up.

2. Self-Care: Yes, your program needs lots of attention, but we tend to forget about ourselves. Sleeping, eating and even things as simple as setting a specific time when work ends are important in ensuring long-term success and sustainability, not only for the program but also for the teacher. Students notice self-care. And we need to care for ourselves in order to be more present for our students.

3. Always remember your WHY: As we continue with our busy lives, schedules and performances, and as our music programs start to run like well-oiled machines, things can become stagnant, where the focus is on the result, rather than the process. The process is the why — taking students from not knowing anything about music to being national performers — and all of the meaning that students take out of that process — makes what we do vitally important. We cannot simply focus on the student outcome of “learning an instrument,” “performing for whomever” or even “Keller Middle School — Superior.” The sense of community is why we do what we do, and we must remember that.

Trevor Tran

Trevor Tran

Head of Performing Arts, Director of Vocal Arts

Fort Myers High School

Fort Myers, Florida

1. The structure of learning cannot be built without the foundation of relationships

2. You can’t pour into your students if you are empty

3. You absolutely deserve to be where you are, if you put in the work

Jabari Tovar

Jabari Tovar

Instrumental Music Teacher, Percussion Specialist

Salem Public Schools

Salem, Massachusetts

1. Have a plan. Plan out your goals for the school year and how you’ll implement them (dream big but be realistic). Plan out how much time it’ll take to get your students where you want them to be. Plan to take time for yourself! Teacher burnout is real and doesn’t help anyone.

2. Remember, everything you do must be for your students. If you try something and it doesn’t work out, that’s OK. The key is to always keep the students in mind.

3. Be honest. Students appreciate transparency. We tell our students that making mistakes is OK, but sometimes we as teachers don’t give ourselves the same grace. Own it, learn from it and move on.

1. Be curious, be brave and ask as many questions as possible that come to your mind. There’s someone there to help you who has been there before. They certainly helped me.

2. Give yourself grace. You will make some mistakes. Just try not to make the same ones. Also, don’t be afraid to say, “I don’t know.” Students will value your honesty with them and your honesty with yourself.

3. Join your local and national professional music organizations (NAfME, ACDA, BOA, etc.). Networking with fellow music educators is extremely valuable in our professional development.

1. Keep high standards. Students will rise to your expectations and will be thankful in the long run for being held to them.

2. Don’t be afraid to take risks and chances. Your students will surprise you and learn things you didn’t think were possible.

3. Ask for help. If you’re struggling to figure out everything it takes to run a music program, you’re not the only one! Other educators have their tricks that work for them. Don’t be afraid to reach out to those in your community with more experience. They want to help!

1. Pace yourself and accept your reality. So many times, we envision our perfect ensemble. Work the ensemble in front of you to progress to be the desired ensemble that you envision. It takes day-by-day building. Give yourself and your students grace; it takes time.

2. Become a connected educator. Advocate for your program by building relationships with students, parents, faculty, alumni, administration and the community. Remember that you are not alone. Communicate with your ensemble’s village.

3. Be passionate. Continuously show love for your discipline. Always be at your best. Demonstrate love for your craft. It will become contagious. This contagious spirit will become enjoyable for all.

1. Find your tribe. Surround yourself with a community of support and people who you can go to for help when you’re stuck. It’s so important to have people who can help you work through a problem, remind you of upcoming deadlines or calm you down when you’re in a panic. It’s okay to ask for help — you’re not in this alone!

2. You’re going to make mistakes, and that’s OK. We’ve all been there — we have all forgotten to turn in grades, respond to that parent email or remind students about their concert attire. These are all learning experiences, and you will learn from them. It doesn’t mean you “failed,” it means you’re growing!

3. Take time for reflection. It’s going to be hectic and you’re going to be overwhelmed sometimes, but take time to reflect on what you’re doing correctly and celebrate those small victories. Likewise, reflect on things that could use some improvement and get creative about ways to address those situations. Use your tribe to celebrate and help you!

1. Video record your teaching and conducting on a weekly basis. This will urgently refine your own delivery/tone, pacing of information, ear training, etc.

2. Find a positive mentor teacher in your life who is dedicated to your students’ growth, dedicated to your growth as an educator and constructively honest in conversation. (Thank you, Dr. Joshua Boyd, Ryan Murrell and countless others, for being my mentors.)

3. Develop curricula through Understanding by Design (UbD) / Backward Design. Begin with the end in mind with all things.

James Sepulvado

James Sepulvado

Performing Arts Department Chair, Associate Professor of Music

Cuyamaca College

Rancho San Diego, California

1. Always remember the music and people. If your college training was anything like mine, the things that matter most are not discussed as much as they should be. The most important things about this job are music and people. If you wake up on fire to make music every day, and you care about your students deeply as people, then everything else about the job will come with time. If you aren’t passionate about music and/or you don’t care about your students, there is nothing you can learn that will make up for that.

2. To do this job well requires about 300 hours of work a week. You must get comfortable with the fact that there will ALWAYS be more work to do than can be done. Once you figure that out, then learn how to get better at delegating, training, asking for help and prioritizing your time.

3. The truth is in the score. This somewhat cryptic saying comes from Elizabeth Green and it is a way of saying that we are not the source of energy when you conduct. We are the conduit through which the music passes, and it is our job to do everything we can to communicate the music that wants to pass through us to the musicians in your ensemble and then ultimately to the audience. When you make it about you, whether it’s your ego, your pride or your competitiveness, you are missing the point. The more you make it about the music and what your students need, the more powerful your music-making powers will become

1. Make sure you are organized, and don’t be afraid to ask for help if you need it.

2. We call it “playing music” for a good reason, so remember to make sure that you and your students get to have some fun doing music stuff in your class. If you don’t think it is important, if you don’t enjoy it, then it isn’t realistic to think that your students will, too.

3. Discipline and respect are essential to good music-making in the classroom, so be sure to find an approach that fits your personality and demeanor. It may be difficult at first — maybe you are concerned that the students won’t like you — but in the long run, they will lose respect for you and stop liking you anyway if you aren’t able to respect everyone’s time by decisively addressing disciplinary issues.

1. Don’t overlook middle school and middle schoolers! It is a great place with fantastic students. Be open to jobs at the middle school level, it’s a very special place where you can make a huge impact.

2. Give yourself five years! A fantastic mentor told me this at the beginning of my career, and it’s been a game changer. The first five years are when you are experimenting and figuring it all out — and these first years are tough! But around year five, you start to feel settled, and you have the confidence that you know what you are doing. Never stop improving and give yourself some grace those first years.

3. Create an organized system for all your digital and physical files from day one! You will save yourself so much time if you always know where things are. Even if you change it later, at least you have somewhere to start.

1. Keep your desk clean. The entire enterprise runs through your office.

2. Keep your due dates and your deadlines from being too close to each other. For example, field trip forms are due to the office on Friday, so they are due to the director on Tuesday, NOT Thursday.

3. Record yourself teaching. Monitor your talking versus teaching ratio. Feedback is one of the most significant drivers of growth.

1. Don’t be afraid to ask for help! I felt like I could barely keep my head above the water my first year, and that’s OK! Being a new teacher is scary sometimes and there are a lot of things you don’t learn about in college.

2. Growth takes time. When you try new things or try to turn a program around, you won’t see results right away. In fact, you may see things get worse before they get better. Stay the course, and be patient. You will see those changes, but it can take years to turn a program around.

3. Set boundaries. Being a music teacher is hard work. We oftentimes provide the only safe space our students have and that leads to a lot of sharing. It’s important to be there for your students, while also setting boundaries to protect your own emotional well-being and mental health. Boundaries are important.

1. Connect with your community. Whether it’s your school district, state or somewhere else, find experienced teachers who you can turn to with questions and gain insights from. Music teachers often feel isolated, but in building your network, you will know you are supported and have a team of cheerleaders behind you!

2. Set boundaries. There’s so much pressure in the professional world, especially in the teaching sphere, to go above and beyond. There is nothing wrong with having high expectations, but burnout is not a badge of honor. Do everything in your power to leave work at work and find something truly recreational or relaxing to include in your routine.

3. It’s just music! Mistakes happen and the first year of teaching certainly has a huge learning curve, but remember that your job is to make music with children — never lose sight of the joy that music brought you, and enjoy the wonderful opportunity you have to bring joy, wonder and success to your students!

Paul Lowry

Paul Lowry

Director of Bands, Percussion and Jazz Studies

Department Chair, Performing Arts

Del Sol Academy of the Performing Arts

Las Vegas, Nevada

1. Routines and structure are key.

2. Give your students reasonable opportunities to make responsible choices.

3. Work hard but have fun doing it.

1. Learn the names of your office staff, counselors and custodians. Treat them with kindness. They hold the walls together. Music programs demand more than other subjects and having a good relationship with these people will make a difference.

2. Ask, beg and borrow. All those great ideas, activities and assignments your colleagues have? Chances are they got them from someone else. We are here to support one another. So, ask for a copy, ask for their thoughts, ask if you can use it. I bet they’ll say yes.

3. Never forget that your students are in your class by choice. The students in front of you choose to participate in music, for one reason or another. It is your responsibility to create an environment in which they want to stay, and an experience in which they thrive.

1. Give yourself GRACE! There will be trial and error and moments that you don’t “get it right.” Realize you aren’t the first and won’t be the last to experience those feelings, learn from them and give yourself grace as you move forward.

2. Plan ahead and be prepared but be ready to PIVOT. Proper preparation allows you to be confident in your instruction but always be prepared to pivot and try something else if need be in order to best serve the needs of your students.

3. Remember that “there’s more.” Think outside the box. Allow your students to think outside the box. All great innovations started with an idea!

1. Be a good human, be patient and allow yourself some grace.

2. Continue to learn and improve your teaching and performance skills so that you can teach students at every level.

3. Create an inclusive and diverse learning environment that is welcoming for all students!

1. It’s OK not to know everything. Even now, I will still get asked about a fancy fingering or music history question that I don’t know the answer to right away. Just go do your homework and share your findings. Those questions may knock your “but I’m a musician!” pride down a notch, but they will make you a better teacher.

2. Take risks! Want to try something you saw online? Have a weird idea to teach a musical concept? Try it! The worst thing that will happen is that it doesn’t give you the results you were hoping for, and you move on to try something else.

3. Be empathetic. If I could compare my first year to now, the amount of empathy I have for my students and their families has grown exponentially. People are dealing with so many outside and uncontrollable factors that sometimes music is their only saving grace, or alternatively, it gets pushed to the side. Instead of taking offense, find out how you can help.

Pick any three from below:

1. Don’t be afraid of mistakes, just try not to repeat the big ones.

2. Go for it! Don’t wait until you know all the steps to join the dance.

3. You’ll never forget your first year, so enjoy it the best you can.

4. The hard part about your first year is the psychoanalysis that follows every rehearsal. You spend so much time thinking about the ins, outs and what ifs that occurred or didn’t occur. This tip is simple: Only spend time thinking about what you can fix in the next rehearsal, everything else is folly.

5. Don’t let the stuff you can’t control rent space in your brain.

1. Ask many questions! The first year of teaching is difficult for everyone.

2. Think outside the box. There is a world of music to explore across multiple cultures and races.

3. Talk to your students. Ask them how their day or weekend was. Ask about their baseball games, dance competitions, etc. Make your students know that they belong and that you care about what’s going on in their lives.

1. Find a mentor who you trust and admire. There is always a teacher with more experience waiting and willing to help guide you in the right direction. No teacher worth their salt wants to see you fail!

2. Get out of your band hall and see master teachers work their craft. Go to all types of conferences, camps and other schools to absorb all the information you can!

3. Be stubborn about your goals and flexible about your methods. Just because a plan is not working the first time (or ever) does not mean the goal should be trashed. That is the beauty of the alphabet … if Plan A will not work, there are 25 more letters from which to choose! Be flexible enough not to panic and destroy the momentum you’ve created!

1. Find places where you have safe opportunities to teach and implement what you learned in school, ideally with role models around where you can learn real teaching experiences and techniques.

2. Design and plan → Implement → Self-reflect → Improve. Do this for the rest of your life! We need to be constant thinkers and be the first person to give feedback to ourselves.

3. Be meaningful all the time. We are changing the world, and it takes a lot! Show your students that there is always a pathway and that you’re willing to guide and support them

1. Find your people and collaborate on everything

2. Get organized. Otherwise, you won’t have enough time to do anything but stay afloat, which is bad for students

3. Have a clear sense of your learning objectives. Are the things you are doing actually addressing those objectives? Constantly ask yourself constantly “why are we doing this?”

1. Embrace the process of becoming a better teacher. You won’t always get it right, so embrace those mistakes and grow from them.

2. In the great words of one of my many mentors, Jeffrey A. Murdock: “Teach the kids in front of you, not the kids you wish you had.”

3. When students feel confident, that they belong, that can be their authentic selves, and that they are being pushed to a high level of excellence, you have created “The Ultimate Classroom Culture.”

1. Trust your abilities as a musician, educator and director. Your students are capable of so much, so don’t be afraid to challenge them to sound musical — you know what that sounds like. Don’t feel obligated to say yes to every request for your group. You know what is reasonable and possible — don’t get pushed around.

2. Make connections with both music and non-music colleagues. They share the same students and can offer a lot of advice. There are a lot of times when you can feel isolated because of how busy you are, so it is helpful to know you’re not.

3. This may sound scary, but your students notice everything. They notice if you’re having a good day or a bad day (my students notice when I don’t end rehearsal by saying have a great day!), they notice how you interact with and support (or don’t support) them, their peers or your colleagues. So, treat everyone with fairness and kindness. Along those same lines, this is a thankless job, so even if you don’t feel appreciated, know that you are.

1. Exemplify a growth mindset. The best teachers are constantly learning and adapting.

2. Put your students first. Often, this means questioning the status quo, being skeptical of things that “have always been done this way,” prioritizing student choice over compliance, and leaning into discomfort in order to advance systemic change.

3. Schools are learning institutions, not entertainment venues. Music education should be about liberating students’ creative voices and seeking musical growth for all, not just about progression of technical skills and competitions. In my opinion, concerts should be an optional component of a curriculum, not the primary way of demonstrating learning outcomes. “Teaching to the concert” is akin to “teaching to the test” and does not result in well-rounded, literate or imaginative musicians.

1. Find your voice and encourage your students to find theirs as well.

2. Never be afraid to say you don’t have the answer. I think when we show up in certain spaces there is a misunderstanding that educators must have all the answers. The moment I was able to celebrate that I am a life-long learner, I was able to realize how incredible my network of scholars on any area was — and they were at my disposal! I celebrate not having all the answers for my students because it allows me to open up my network to them as well.

3. You can love what you do and still be burnt out. I don’t believe the saying, “If you choose what you love to do, you never have to work a day in your life.” Sometimes, the work is hard and draining. Having a good work/life balance is important so that you never lose sight of why we are in this profession in the first place

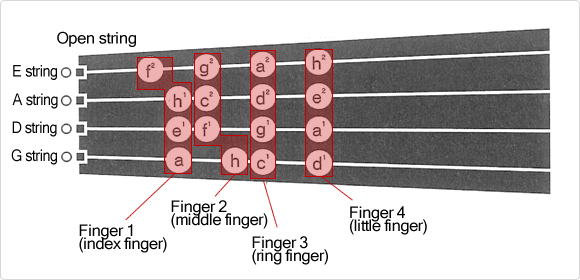

1. Teach beginners early in your career. Nothing strengthens your pedagogy like teaching a child to play an instrument from square one. They only know what you’ve taught them. It’s the ultimate litmus test of your ability as a teacher. Furthermore, you’ll intimately learn the instruments, making you a better ensemble teacher!

2. Learn to play every instrument you teach. The best decision I ever made for my pedagogy was to learn how to play a new instrument every summer when I was young and still had the time. I can still remember the summer I spent practicing clarinet. I gained a strong appreciation for what it feels like to be a beginner again, and I figured out how to troubleshoot all the strange sounds I was hearing in class but wasn’t sure how to address.

3. The first three years are the hardest. One of my mentors once told me that your first year you’ll be drowning. Your second year you’ll tread water. The third year you’ll start to swim but be unsure of the destination. Once you hit the fourth year, you’ll start to swim with purpose. This couldn’t have been more accurate for me, and I’ve seen it ring true for so many of my former student teachers over the years.

1. Everything you know matters — your experiences, your pedagogical and musical knowledge. However, you must remember that you are teaching humans in front of you, each of whom have hopes and dreams about “what band is,” what they hope to accomplish and what it means to be a part of an ensemble. Additionally, they have worries and stressors in other areas of their lives that will affect their performance in your class. I think it is important that as music educators, we address the entire individual and be a positive force for good in their lives.

2. Students will feed off of your genuine joy of music-making. They will mimic your stress and frustration if you show those emotions, but they will also mimic your vulnerability, technique and passion. Lead by example and demonstrate sensitive and encouraging musical energy.

3. Get students to buy in to what you are doing through building genuine relationships, showing them that you care and fostering trust. Especially if you are stepping into a high school band program, I strongly recommend not changing about 90% of the program norms for the first year. The 9th graders in front of you likely never encountered your predecessor, but to the 12th graders, you are the teacher who took the job of “their” band director. Show them you are on the same team and want the same thing through honoring their band experience and add new things where you can.

1. Utilize all the resources available to you. It’s important to take advantage of any grant, partnership or help from the community to enhance your program. Students will notice how much you are investing in them and their success.

2. Celebrate the growth of your students as much as possible, no matter how big or small. Students want to be seen and heard. They need positive reinforcement in their lives to provide them with motivation to achieve excellence.

3. Collaborate with your department and seek help when needed. Do not try to do everything on your own. We can grow and support each other and our programs.

1. The first year was hard for all of us — keep showing up and asking for help. It will get easier! Just remember to be YOU! You’re the only you there is on this planet, so be yourself and don’t try to be like anyone else (it’s OK to not follow the imaginary ruler or yardstick of life — just do you!)

2. Make sure you’re eating well and sleeping enough — you can’t rock a classroom full of folks if your engine isn’t running correctly

3. It’s OK to say no, and it is more than OK to ask for help — not only in year one but forever. I wouldn’t be able to do anything I do today without my mentors. Collaboration is one of the keys to loving life!

1. Document everything! Your first year will always be the year in which you lay the groundwork/foundation for the rest of your career. Keep every physical/digital file that you use and store it for future reference. They will come in handy later!

2. Ask lots of questions and seek lots of answers. Let your mind be inquisitive. You never know where those generated ideas will take you and your students!

3. Enjoy each moment and take time to care for yourself whenever you can. Try to not bring the work home as much as possible. If you are great with your students, strive to be even greater with your family, friends, spouse, children, pets, etc. Maintaining a healthy work-life balance will give you longevity and energy in this field of work.

Check out tips for first-year music teachers from the 2025 “40 Under 40,” 2024 “40 Under 40,” 2022 “40 Under 40” and 2021 “40 Under 40” educators for more invaluable advice!

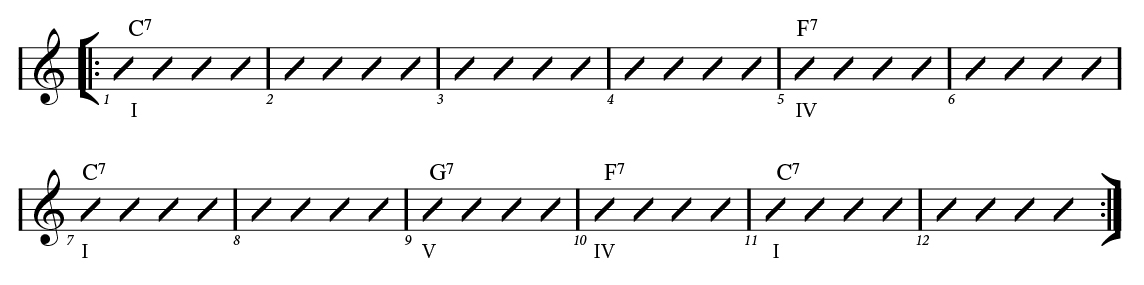

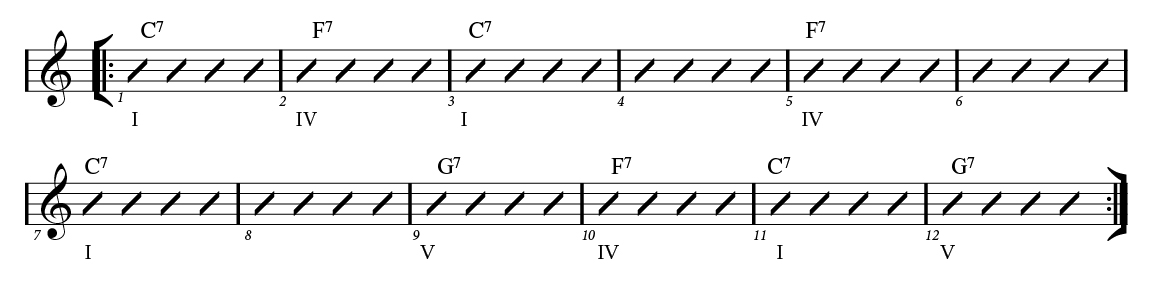

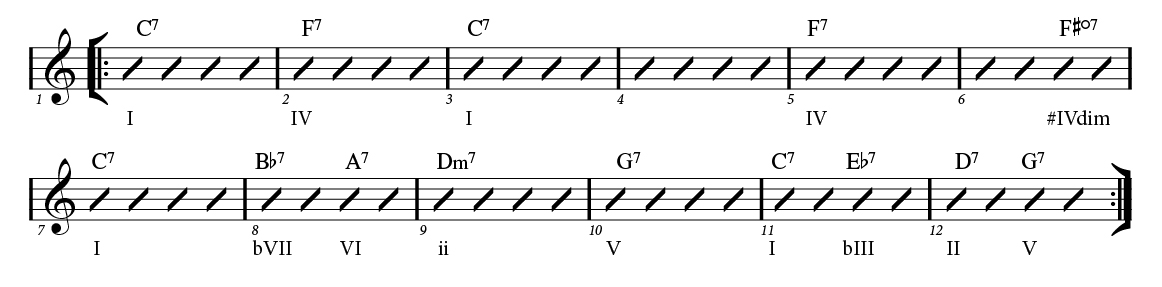

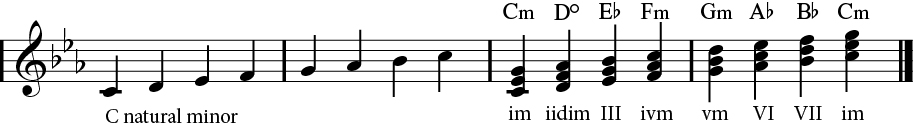

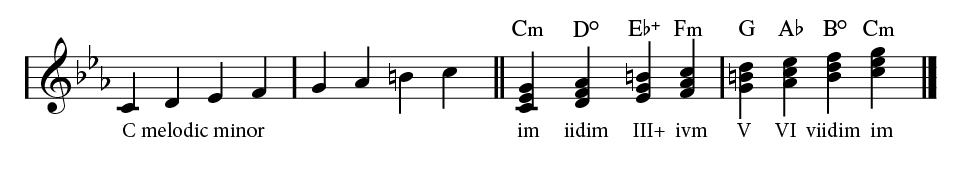

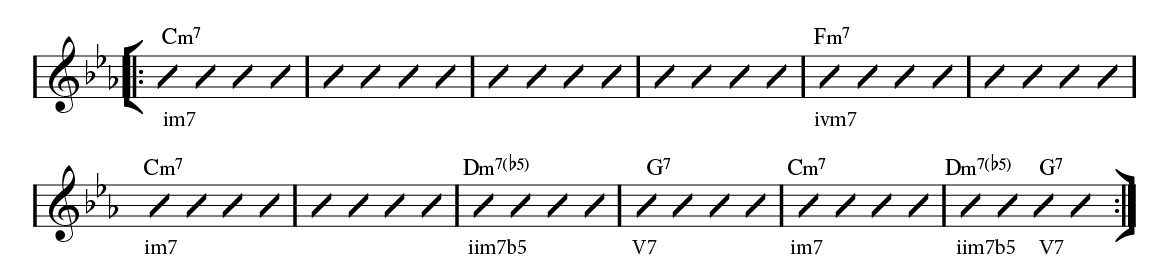

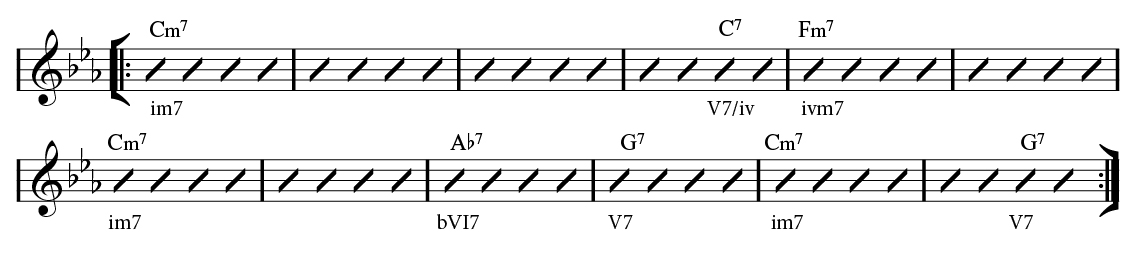

Before I dive into directing tips, let’s look into the most common subgenres of jazz that I taught: big band Latin, swing and blues.

Before I dive into directing tips, let’s look into the most common subgenres of jazz that I taught: big band Latin, swing and blues. When I first stepped in front of a jazz band, a lot of questions flooded my mind: How do I move? How do I cue instrumentalists? What kind of energy should I embody for these students?

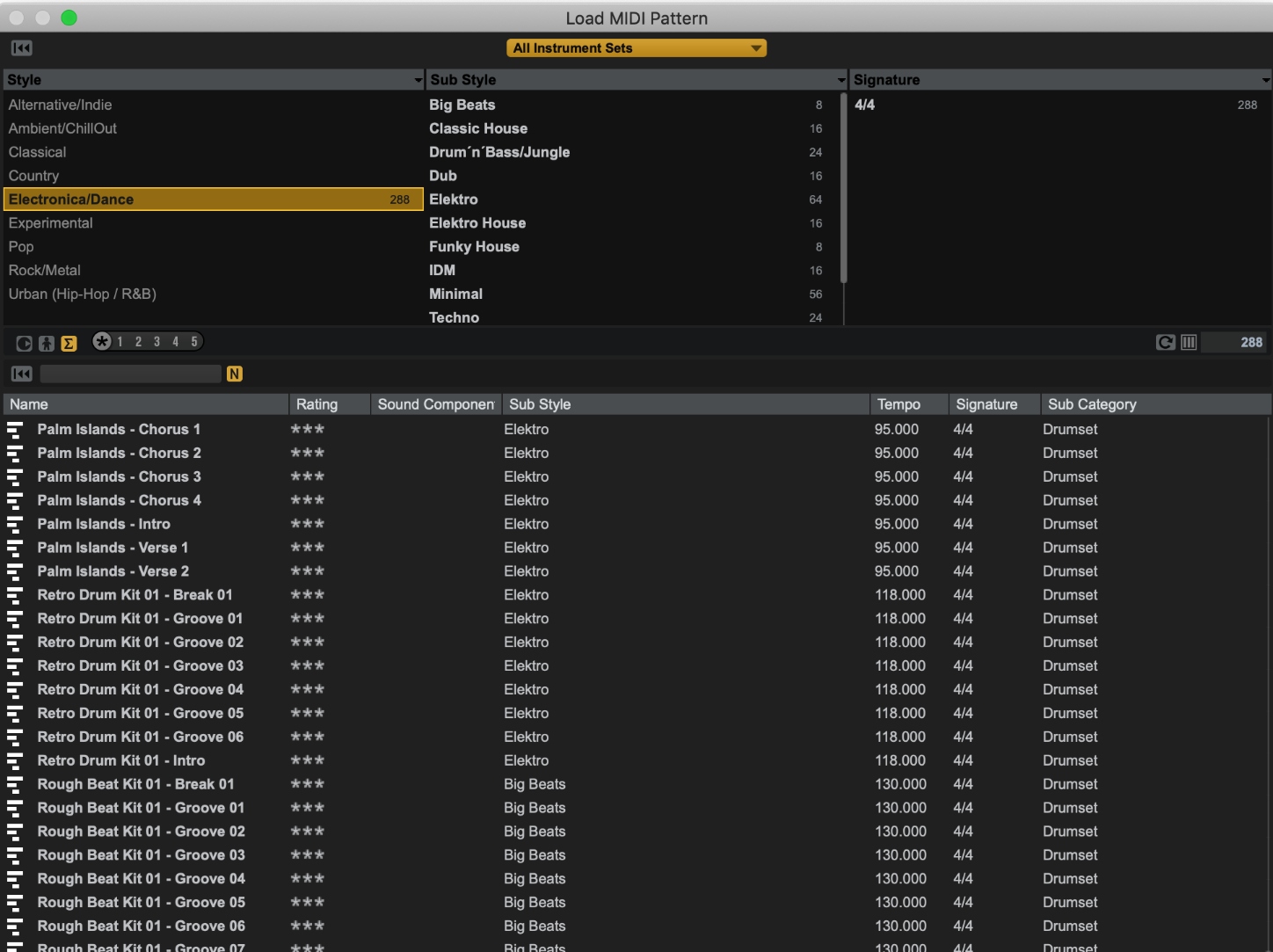

When I first stepped in front of a jazz band, a lot of questions flooded my mind: How do I move? How do I cue instrumentalists? What kind of energy should I embody for these students? If you’ve been asked to begin directing a jazz band, you’ll need some repertoire. Pepper in some rock or pop tunes like “Eye of the Tiger,” but here is a short list of standards and charts to get you started:

If you’ve been asked to begin directing a jazz band, you’ll need some repertoire. Pepper in some rock or pop tunes like “Eye of the Tiger,” but here is a short list of standards and charts to get you started:

When I thought about leaving teaching, I surmised that quitting would fix all my problems. In one situation,

When I thought about leaving teaching, I surmised that quitting would fix all my problems. In one situation,  Long Hours and Few Boundaries: I noticed that my energy levels varied. On Mondays and Tuesdays, I usually arrived to the office early, skipped lunch and stayed late. I justified this by seeking the reward later in the week for not having to work as much. On Wednesday, I started the day with the same schedule, but by 11 a.m., I was drained.

Long Hours and Few Boundaries: I noticed that my energy levels varied. On Mondays and Tuesdays, I usually arrived to the office early, skipped lunch and stayed late. I justified this by seeking the reward later in the week for not having to work as much. On Wednesday, I started the day with the same schedule, but by 11 a.m., I was drained. I still managed an exercise routine, but what was once a positive part of my day turned out to be a struggle. I never like having to talk myself into doing something that I used to enjoy.

I still managed an exercise routine, but what was once a positive part of my day turned out to be a struggle. I never like having to talk myself into doing something that I used to enjoy. Just focus on the positive, calm down, and stop worrying!

Just focus on the positive, calm down, and stop worrying! We can only fix one thing at a time. It’s not fair, but it’s reality.

We can only fix one thing at a time. It’s not fair, but it’s reality. Teaching may not be for everyone. And if it’s not, please do what is best for you. However, I urge anyone considering a change to follow their trail of breadcrumbs. Will that new profession make things better? Or will it run the chance of being a semi-permanent solution to a temporary problem?

Teaching may not be for everyone. And if it’s not, please do what is best for you. However, I urge anyone considering a change to follow their trail of breadcrumbs. Will that new profession make things better? Or will it run the chance of being a semi-permanent solution to a temporary problem?

As a teacher, I continue this approach to music programming for my ensembles. We kick off each school year with a student survey. I also ask my students to give a copy of the survey to one person they know who is not in band so we could get a broader understanding of the most popular tunes at the time. The survey has just a handful of questions, along with room at the end for students to suggest what they would like the band to play this year. The band staff and our student leaders will then sort through all the surveys to find the most popular tunes and then discuss which songs we would like to arrange and when they would be performed. Knowing our students’ musical interests and having a sense of the school’s musical tastes as a whole helped us relate to students and build esprit de corps throughout the building.

As a teacher, I continue this approach to music programming for my ensembles. We kick off each school year with a student survey. I also ask my students to give a copy of the survey to one person they know who is not in band so we could get a broader understanding of the most popular tunes at the time. The survey has just a handful of questions, along with room at the end for students to suggest what they would like the band to play this year. The band staff and our student leaders will then sort through all the surveys to find the most popular tunes and then discuss which songs we would like to arrange and when they would be performed. Knowing our students’ musical interests and having a sense of the school’s musical tastes as a whole helped us relate to students and build esprit de corps throughout the building. I am a strong advocate for student leadership. I believe that it is one of the best ways to empower tomorrow’s leaders in our field. One strategy that has worked very well for my programs is establishing student-led committees for our concert calendar. Because students know the importance of relevant repertoire selection across all aspects of the program, we have show-planning and dance-routine committees for our marching band, an arranging team that helps compose popular tunes for our concert and jazz bands, and a cool group known as “chamber grooves” that include students who love chamber music and would compose trending tunes and top 40 hits for our smaller ensembles.

I am a strong advocate for student leadership. I believe that it is one of the best ways to empower tomorrow’s leaders in our field. One strategy that has worked very well for my programs is establishing student-led committees for our concert calendar. Because students know the importance of relevant repertoire selection across all aspects of the program, we have show-planning and dance-routine committees for our marching band, an arranging team that helps compose popular tunes for our concert and jazz bands, and a cool group known as “chamber grooves” that include students who love chamber music and would compose trending tunes and top 40 hits for our smaller ensembles.

I worked at one school where the athletic account covered drumline bleacher stands and pep-band drum sets. It also provided funding for five pep band charts annually. (I was appreciative of this and let a coach or two pick some of the pieces that we ordered.)

I worked at one school where the athletic account covered drumline bleacher stands and pep-band drum sets. It also provided funding for five pep band charts annually. (I was appreciative of this and let a coach or two pick some of the pieces that we ordered.) Ask the Community for Money: Community members such as small businesses, alumni and even former music parents can provide financial support. Be clear and concise in your request. Be mindful of the companies that want to sponsor you. Reputation and ethics are more important than fundraising.

Ask the Community for Money: Community members such as small businesses, alumni and even former music parents can provide financial support. Be clear and concise in your request. Be mindful of the companies that want to sponsor you. Reputation and ethics are more important than fundraising. I Asked and They Said Yes! Now What?

I Asked and They Said Yes! Now What? Outsourcing is OK: I was often in the position of wanting to do auditions or placements but not having the money or time. Outsourcing these jobs is OK if your district is fine with it. I never want to take work away from those who depend on judging or clinics, but if you have a larger program and little funding, consider completing these digitally. We moved to pay $5 for initial chair placements. Students spoke an ID number into a recorder and then performed their excerpts. I compiled the digital files and emailed them to off-site adjudicators who were professionals on each instrument. Our band parent association paid the adjudicators $5 per audition, and they emailed back results and feedback to over 125 students within 24 hours. Remote or outsourced judges are also an excellent option for a rural school that may not have regular access to other music teachers.

Outsourcing is OK: I was often in the position of wanting to do auditions or placements but not having the money or time. Outsourcing these jobs is OK if your district is fine with it. I never want to take work away from those who depend on judging or clinics, but if you have a larger program and little funding, consider completing these digitally. We moved to pay $5 for initial chair placements. Students spoke an ID number into a recorder and then performed their excerpts. I compiled the digital files and emailed them to off-site adjudicators who were professionals on each instrument. Our band parent association paid the adjudicators $5 per audition, and they emailed back results and feedback to over 125 students within 24 hours. Remote or outsourced judges are also an excellent option for a rural school that may not have regular access to other music teachers.

Over the course of the unit, students were introduced to foundational aspects of sociocultural identity (visible and invisible), intersectionality, and they informally mapped and reflected on their own identity. They were encouraged to describe ways in which the components of their identity are represented and/or absent in the wind band music that they have performed, studied and consumed over their lifetime. The student responses were eye-opening.

Over the course of the unit, students were introduced to foundational aspects of sociocultural identity (visible and invisible), intersectionality, and they informally mapped and reflected on their own identity. They were encouraged to describe ways in which the components of their identity are represented and/or absent in the wind band music that they have performed, studied and consumed over their lifetime. The student responses were eye-opening. The student goal of programming concerts that more closely mirror our community has led to a multi-semester, student-driven research and grant-writing project that has resulted in successfully authoring three grants to diversify our available music library and concert programs. We have been awarded over $6,000 for new music! One award, an internal faculty-student research grant through Slippery Rock University, involves students developing a consortium to commission a composer to write a new piece for wind band that will be performed in the fall of 2023.

The student goal of programming concerts that more closely mirror our community has led to a multi-semester, student-driven research and grant-writing project that has resulted in successfully authoring three grants to diversify our available music library and concert programs. We have been awarded over $6,000 for new music! One award, an internal faculty-student research grant through Slippery Rock University, involves students developing a consortium to commission a composer to write a new piece for wind band that will be performed in the fall of 2023. The students drew several conclusions. First, this project cannot accurately account for the vast multitude and complexity of identity and diversity. Second, the students acknowledged that invisible diversity is not always easily accounted for nor is it always freely expressed. With these limitations in mind, the students chose to narrow their focus on three aspects of diversity: gender/gender identity and expression, race/ethnicity, and membership in the LGBTQIA2S+ community.

The students drew several conclusions. First, this project cannot accurately account for the vast multitude and complexity of identity and diversity. Second, the students acknowledged that invisible diversity is not always easily accounted for nor is it always freely expressed. With these limitations in mind, the students chose to narrow their focus on three aspects of diversity: gender/gender identity and expression, race/ethnicity, and membership in the LGBTQIA2S+ community. To diversify the library, the students set the goal of identifying resources in the form of grants that might apply to this project. Focusing efforts first on internal grants, the following grant applications were submitted through Slippery Rock University for two separate projects. Benjamin Johnston, an undergraduate oboist and officer in the SRU Symphonic Wind Ensemble, served as co-author of each grant application. The grants were as follows:

To diversify the library, the students set the goal of identifying resources in the form of grants that might apply to this project. Focusing efforts first on internal grants, the following grant applications were submitted through Slippery Rock University for two separate projects. Benjamin Johnston, an undergraduate oboist and officer in the SRU Symphonic Wind Ensemble, served as co-author of each grant application. The grants were as follows: The two projects are now at the stage where financial resources have been generated to successfully move forward and we could not be more excited or grateful. As we transition into carrying out these projects, it is an opportune time to reflect on the impact that this has had on the students and the program. As a teacher, it has been humbling to watch students engage with issues of diversity within the profession. Over the course of the journey, students have been able to:

The two projects are now at the stage where financial resources have been generated to successfully move forward and we could not be more excited or grateful. As we transition into carrying out these projects, it is an opportune time to reflect on the impact that this has had on the students and the program. As a teacher, it has been humbling to watch students engage with issues of diversity within the profession. Over the course of the journey, students have been able to:

All humans procrastinate to some level, and that’s due to a cognitive bias: They falsely believe that 1) tasks will magically become easier, and 2) we’ll have more time for the task. According to research published in 2022 in the journal

All humans procrastinate to some level, and that’s due to a cognitive bias: They falsely believe that 1) tasks will magically become easier, and 2) we’ll have more time for the task. According to research published in 2022 in the journal  Try the 15-minute trick. Set a timer and work on your task for 15 minutes. Just 15 minutes. When the timer goes off, you may find that you’ve gained some traction and are getting into the zone. Keep going if you want to. If not, take a break. Play the bassoon, pet your cat, call your sister. Then take another 15-minute whack. Time-management pros call this strategy “microproductivity.”

Try the 15-minute trick. Set a timer and work on your task for 15 minutes. Just 15 minutes. When the timer goes off, you may find that you’ve gained some traction and are getting into the zone. Keep going if you want to. If not, take a break. Play the bassoon, pet your cat, call your sister. Then take another 15-minute whack. Time-management pros call this strategy “microproductivity.”

The conference was shocking in many ways. I first attended recorder workshops where I felt most at home because I play the flute. The classes that pushed me out of my comfort zone were the interpretive dance sessions on the second day. I planned to sit and simply watch the workshop, but I quickly learned that that’s not how Orff is done.

The conference was shocking in many ways. I first attended recorder workshops where I felt most at home because I play the flute. The classes that pushed me out of my comfort zone were the interpretive dance sessions on the second day. I planned to sit and simply watch the workshop, but I quickly learned that that’s not how Orff is done. There are three Orff levels after which you are certified in Orff-Schulwerk. You are allowed to take only one level per year, and each level takes at least 60 hours to complete. AOSA recommends completing the levels within seven years, so you retain the material.

There are three Orff levels after which you are certified in Orff-Schulwerk. You are allowed to take only one level per year, and each level takes at least 60 hours to complete. AOSA recommends completing the levels within seven years, so you retain the material.

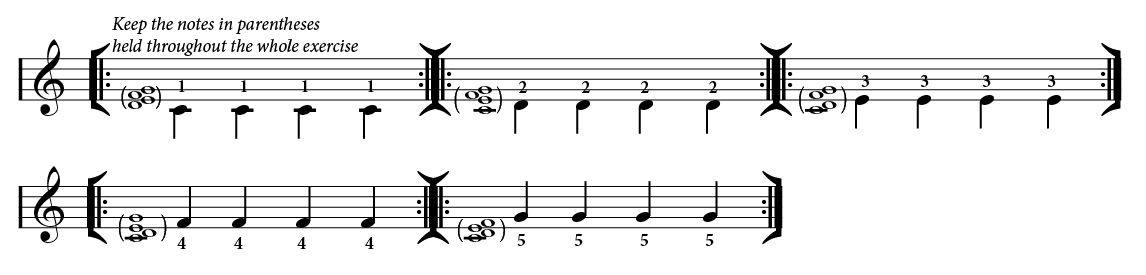

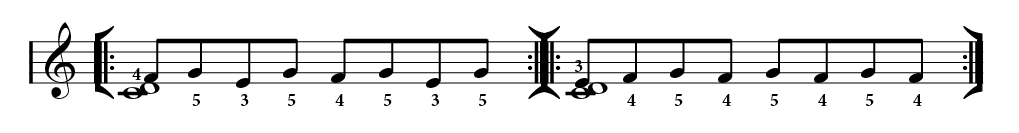

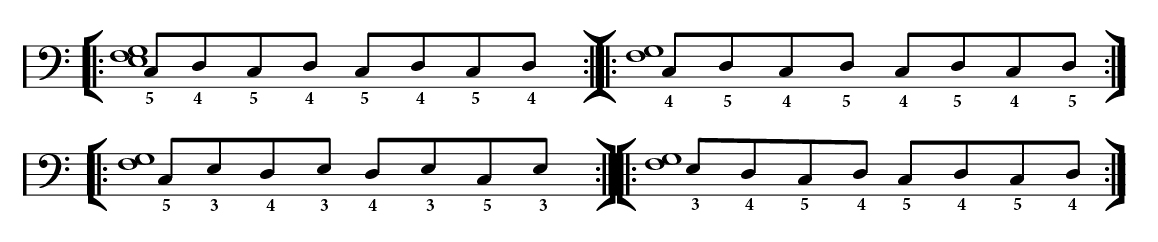

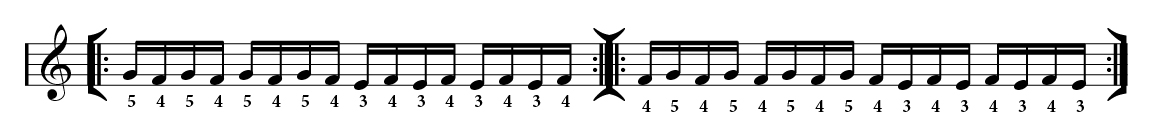

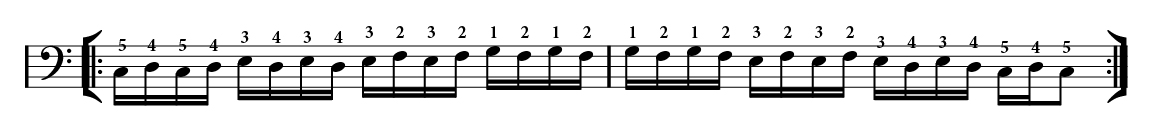

Regardless of your students’ age, music learning should start with the body. One of the six principles of the Kodály philosophy — the body is an instrument — may be used as the basis for learning. It may or may not come as a surprise that many high school students have a hard time keeping a steady beat. If students are lacking the heart of the music, how can we teach them to be music literate in the absence of steady beat?

Regardless of your students’ age, music learning should start with the body. One of the six principles of the Kodály philosophy — the body is an instrument — may be used as the basis for learning. It may or may not come as a surprise that many high school students have a hard time keeping a steady beat. If students are lacking the heart of the music, how can we teach them to be music literate in the absence of steady beat?

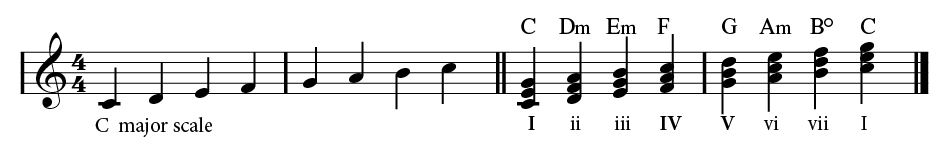

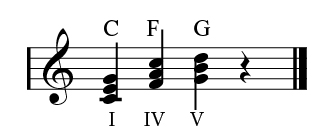

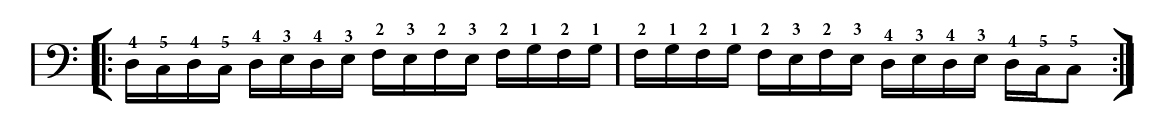

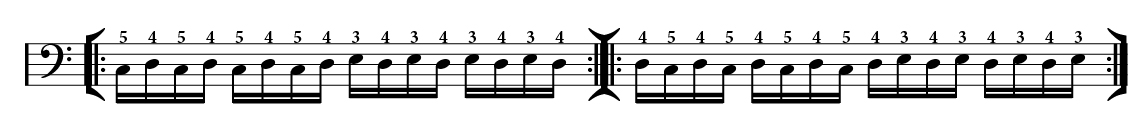

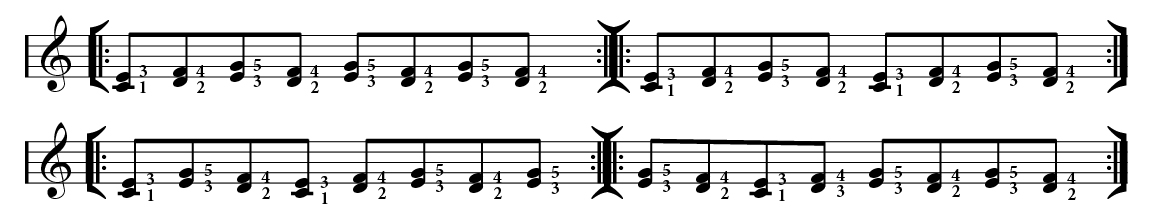

Throughout all these activities, embed music theory so that students can ground their knowledge. Use numbers to count rhythms according to the meter so older students can quickly determine the difference between time signatures. Incorporate relay races or other challenge-type games to identify notes written on the grand staff to ensure that students are accountable for their musical knowledge. If you ever want to get an entire room of high school students completely silent and focused on their listening skills, create a game to correctly identify the intervals of step, skip and leap.

Throughout all these activities, embed music theory so that students can ground their knowledge. Use numbers to count rhythms according to the meter so older students can quickly determine the difference between time signatures. Incorporate relay races or other challenge-type games to identify notes written on the grand staff to ensure that students are accountable for their musical knowledge. If you ever want to get an entire room of high school students completely silent and focused on their listening skills, create a game to correctly identify the intervals of step, skip and leap.

Quick Fixes: I’ve found that quick fixes don’t usually work long-term. We could yell, threaten discipline, pile on false or excessive praise, let too much slide, be too harsh or ignore the problem. These tend to be Band-Aids at best and will sow seeds of discontent at worse.

Quick Fixes: I’ve found that quick fixes don’t usually work long-term. We could yell, threaten discipline, pile on false or excessive praise, let too much slide, be too harsh or ignore the problem. These tend to be Band-Aids at best and will sow seeds of discontent at worse.

Understand Resources: Understand the resources available within your school. Education loves acronyms, and it can be confusing to keep BHT (Behavioral Health Team), BIP (Behavior Intervention Plan) and BMP (Behavior Management Plan) straight. However, speaking with your guidance counselors and social workers about possible resources for students in need can help you react quickly and effectively. We don’t have to do it alone, and — gasp! — someone else might be better equipped than you to help a student’s situation!

Understand Resources: Understand the resources available within your school. Education loves acronyms, and it can be confusing to keep BHT (Behavioral Health Team), BIP (Behavior Intervention Plan) and BMP (Behavior Management Plan) straight. However, speaking with your guidance counselors and social workers about possible resources for students in need can help you react quickly and effectively. We don’t have to do it alone, and — gasp! — someone else might be better equipped than you to help a student’s situation! Escalation / Everyone Loses: Avoid escalating the situation. Some students may feel like they have nothing to lose. For their sake and yours, avoid escalating and arguing. Not saying the first thing that comes to your mind or saying nothing at all could be helpful in stressful situations. Listening is always an effective strategy. Everyone loses when the teacher and student lose their cool.

Escalation / Everyone Loses: Avoid escalating the situation. Some students may feel like they have nothing to lose. For their sake and yours, avoid escalating and arguing. Not saying the first thing that comes to your mind or saying nothing at all could be helpful in stressful situations. Listening is always an effective strategy. Everyone loses when the teacher and student lose their cool. We can consider restorative practices in our classroom (my go-to resource is

We can consider restorative practices in our classroom (my go-to resource is  Not Admitting Mistakes / Not Apologizing: One of my favorite things about growing up in a low-income area and teaching low-income students is the honesty. Remember, some of our students may be living with adult responsibilities at home. Some won’t hold back on letting you know if you’re wrong in delivering content or mistreating someone. Once, in front of the whole ensemble, I got after a kid for missing a rehearsal. The student getting the reprimand didn’t say anything, but another student did.

Not Admitting Mistakes / Not Apologizing: One of my favorite things about growing up in a low-income area and teaching low-income students is the honesty. Remember, some of our students may be living with adult responsibilities at home. Some won’t hold back on letting you know if you’re wrong in delivering content or mistreating someone. Once, in front of the whole ensemble, I got after a kid for missing a rehearsal. The student getting the reprimand didn’t say anything, but another student did. You guessed it: We must walk the walk. Students will absolutely call out hypocrites! Modeling what you consider to be the right behavior is easier said than done. What do I want from my students?

You guessed it: We must walk the walk. Students will absolutely call out hypocrites! Modeling what you consider to be the right behavior is easier said than done. What do I want from my students? Building a relationship with a student and teaching them to respect us is not the end point. If we stopped there, we would be giving the student an unrealistic view of the world — that they only need to adhere to certain rules, guidelines and norms to the people who put significant effort into them. Schools are trying their best to create individualized education programs for every student, and although I applaud these efforts, conformity and social norms are not always a bad thing. People achieve more by working together.

Building a relationship with a student and teaching them to respect us is not the end point. If we stopped there, we would be giving the student an unrealistic view of the world — that they only need to adhere to certain rules, guidelines and norms to the people who put significant effort into them. Schools are trying their best to create individualized education programs for every student, and although I applaud these efforts, conformity and social norms are not always a bad thing. People achieve more by working together.

Holding a flute correctly can be tiring, but holding it incorrectly causes a host of problems, including poor tone and muscle strains or sprains. Flutists are especially prone to neck pain and carpal tunnel, so it is imperative to keep an eye on their posture. Be sure that your flutists sit up straight and curve their wrists into a “C” position. Flutists should not lean their heads to the right (toward the flute).

Holding a flute correctly can be tiring, but holding it incorrectly causes a host of problems, including poor tone and muscle strains or sprains. Flutists are especially prone to neck pain and carpal tunnel, so it is imperative to keep an eye on their posture. Be sure that your flutists sit up straight and curve their wrists into a “C” position. Flutists should not lean their heads to the right (toward the flute).

Another thing that is somewhat related to blowing down is note bending. This is a practice that flutist William Bennett swore by. He encouraged young flutists to bend the pitch of their note both up and down while they practiced long tones. This will help students strengthen their embouchure muscles, familiarize them with their instrument and find their tonal center.

Another thing that is somewhat related to blowing down is note bending. This is a practice that flutist William Bennett swore by. He encouraged young flutists to bend the pitch of their note both up and down while they practiced long tones. This will help students strengthen their embouchure muscles, familiarize them with their instrument and find their tonal center.

When I first became a teacher, I believed that anything less than the top rating at festival meant I was a failure. I had this fantasy about what it meant to be a band teacher. I was going to have the best groups in the area! I was this fun, energetic teacher, my kids would love me, and in turn, they would be amazing musicians simply because I was the person in front of them. I would teach them how to play faster, higher, louder, with more emotion, in tune, with balance. I was going to get my name out there! Thankfully, I learned pretty quickly that this was not reality.

When I first became a teacher, I believed that anything less than the top rating at festival meant I was a failure. I had this fantasy about what it meant to be a band teacher. I was going to have the best groups in the area! I was this fun, energetic teacher, my kids would love me, and in turn, they would be amazing musicians simply because I was the person in front of them. I would teach them how to play faster, higher, louder, with more emotion, in tune, with balance. I was going to get my name out there! Thankfully, I learned pretty quickly that this was not reality. I remember talking to a veteran teacher from a neighboring district about this. He told me, “Kids are just different nowadays. They don’t try any more, they give up and they want everything handed to them. They’re lazy.”

I remember talking to a veteran teacher from a neighboring district about this. He told me, “Kids are just different nowadays. They don’t try any more, they give up and they want everything handed to them. They’re lazy.” Have you ever taught a beginning band or orchestra class? Those first few weeks can be, well, interesting. Those beautiful colorful sounds, screeches, squawks and flubber sounds happen regularly, but we know that they will turn into music soon. We know these noises are part of our students developing their embouchures, bow holds, finger placement.

Have you ever taught a beginning band or orchestra class? Those first few weeks can be, well, interesting. Those beautiful colorful sounds, screeches, squawks and flubber sounds happen regularly, but we know that they will turn into music soon. We know these noises are part of our students developing their embouchures, bow holds, finger placement. How often have you said to a student or section that is not playing or singing out, “I want to hear your mistakes” and meant it? How many times have you said this during rehearsal, and when that mistake happened, you stopped the group and made a comment on the right note or rhythm? Have you ever heard those mistakes and literally applauded that student or section? If not, try it, genuinely.

How often have you said to a student or section that is not playing or singing out, “I want to hear your mistakes” and meant it? How many times have you said this during rehearsal, and when that mistake happened, you stopped the group and made a comment on the right note or rhythm? Have you ever heard those mistakes and literally applauded that student or section? If not, try it, genuinely. Have you ever taught students how to improvise or compose? During these two processes that are highly dependent on failure, we learn what we like and what we don’t. We sometimes use a process of elimination as we work through the kinks.

Have you ever taught students how to improvise or compose? During these two processes that are highly dependent on failure, we learn what we like and what we don’t. We sometimes use a process of elimination as we work through the kinks.

Try this: We have a challenge that we throw out to our groups leading into big show weeks. How long can you go saying, writing (social media/text) and thinking positive outcomes? The more you say, write and think something, the higher the probability that it will come true! Challenge your group and acknowledge that if/when you fall off the positive wagon, you will get right back on. It’s a tough assignment but reminders and encouragement from student leaders in the group will work wonders. And talk about a shift in the culture of the group from this simple exercise — just wait and watch!

Try this: We have a challenge that we throw out to our groups leading into big show weeks. How long can you go saying, writing (social media/text) and thinking positive outcomes? The more you say, write and think something, the higher the probability that it will come true! Challenge your group and acknowledge that if/when you fall off the positive wagon, you will get right back on. It’s a tough assignment but reminders and encouragement from student leaders in the group will work wonders. And talk about a shift in the culture of the group from this simple exercise — just wait and watch! Take time to lay out for your students the physical and mental realities of performance. Physically, their bodies may exhibit some of the responses we have all experienced as performers: rapid heart rate, butterflies in their stomach, sweating, dry mouth, etc. These physical responses are natural, but they can be overcome or even used to your advantage when students are taught how to deal with them.

Take time to lay out for your students the physical and mental realities of performance. Physically, their bodies may exhibit some of the responses we have all experienced as performers: rapid heart rate, butterflies in their stomach, sweating, dry mouth, etc. These physical responses are natural, but they can be overcome or even used to your advantage when students are taught how to deal with them. The post-performance aspect of the mental game may be the most important as it is directly in our control if we choose to accept the challenge! Check out my article,

The post-performance aspect of the mental game may be the most important as it is directly in our control if we choose to accept the challenge! Check out my article,

Arrive Early

Arrive Early Get Connected

Get Connected One of the best things I carry with me is my emergency substitute bag, which includes:

One of the best things I carry with me is my emergency substitute bag, which includes:

Located in Nashville, Tennessee State University, a Historically Black College & University (HBCU), sits in the heart of the place affectionately known as “Music City.” Being in one of the country’s most vibrant cities for live music has certainly helped us in terms of involvement with the greater Nashville community, and we do our best to be proactive in pursuing potential partnerships with organizations within our local area. One of the ways we do this — in addition to the work we do through our memoranda of understanding (MOUs) with outside entities — is through our community music program.

Located in Nashville, Tennessee State University, a Historically Black College & University (HBCU), sits in the heart of the place affectionately known as “Music City.” Being in one of the country’s most vibrant cities for live music has certainly helped us in terms of involvement with the greater Nashville community, and we do our best to be proactive in pursuing potential partnerships with organizations within our local area. One of the ways we do this — in addition to the work we do through our memoranda of understanding (MOUs) with outside entities — is through our community music program.

Many of my colleagues at other institutions often ask how we are able to forge these connections within our community and maintain them for so long. For us, it starts with active engagement and proactive pursuits. Our faculty are constantly forming professional relationships by attending and presenting at conferences, participating in college recruitment fairs, visiting local K-12 schools regularly, serving on the boards of local nonprofits, and constantly publicizing the work we are doing through local news outlets and social media. And with our upcoming historic performances this academic year with our jazz band at the prestigious

Many of my colleagues at other institutions often ask how we are able to forge these connections within our community and maintain them for so long. For us, it starts with active engagement and proactive pursuits. Our faculty are constantly forming professional relationships by attending and presenting at conferences, participating in college recruitment fairs, visiting local K-12 schools regularly, serving on the boards of local nonprofits, and constantly publicizing the work we are doing through local news outlets and social media. And with our upcoming historic performances this academic year with our jazz band at the prestigious