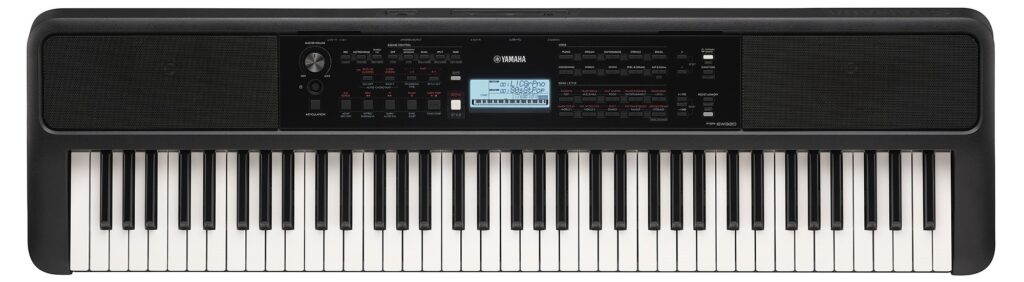

Using the Yamaha MLC-200 Lab Controller in the Classroom

Students work well in groups, particularly if the more advanced students are mentoring the others. But teaching music students in large groups can be challenging for the instructor, for a variety of reasons. For one thing, many schools have students at varying skill levels together in one class. In addition, students playing their instruments while you are trying to instruct the class can be frustrating for everyone involved … and because the student does not hear the lesson and directions, they may later be asking questions that can slow the entire class down.

Enter the lab controller — a communication system widely used in group piano and keyboard classroom settings, from K-12 all the way up to college-level. With these systems, the instructor is able to communicate with students through a headset that has an attached microphone. Students hear the instruction, as well as demonstrations from the teacher’s instrument and the sound of their own instruments, through their headsets, which also have attached microphones. This allows students to communicate with the instructor, as well as with each other — and with no outside noise to disturb either the class members or the instructor, and no noise escaping the classroom either. And because there are many different configurations the instructor can set for a wide range of activities, the dynamic of the group class becomes much more exciting, fun and interesting.

In this article, we’ll focus on the functionality of the Yamaha MLC-200 — the first ever all-digital lab controller.

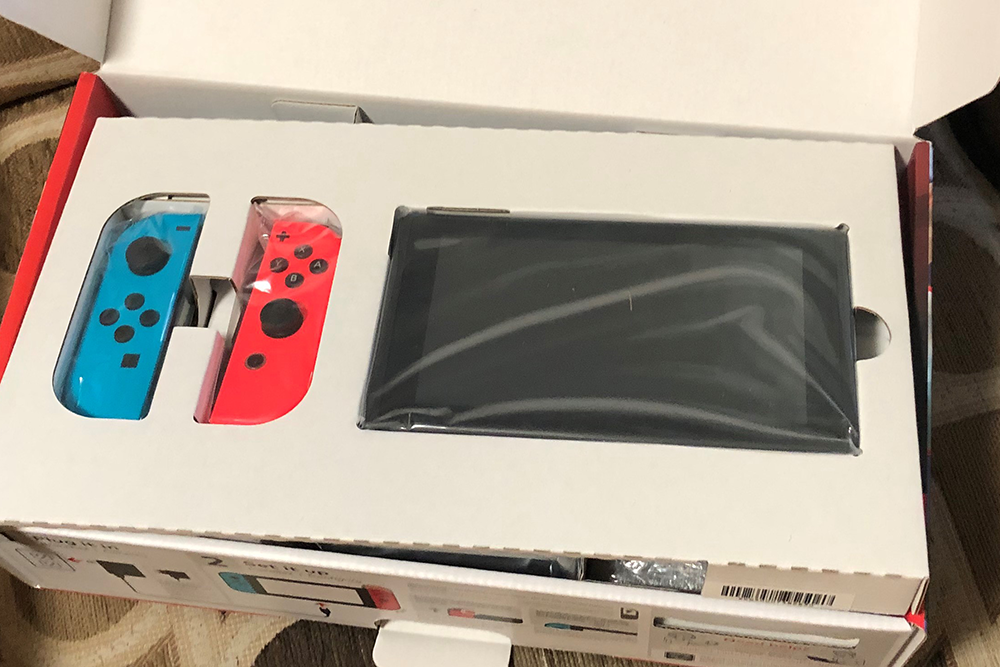

What’s Included

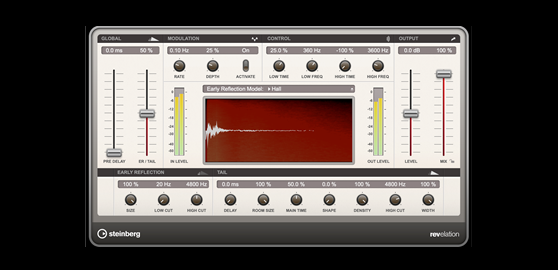

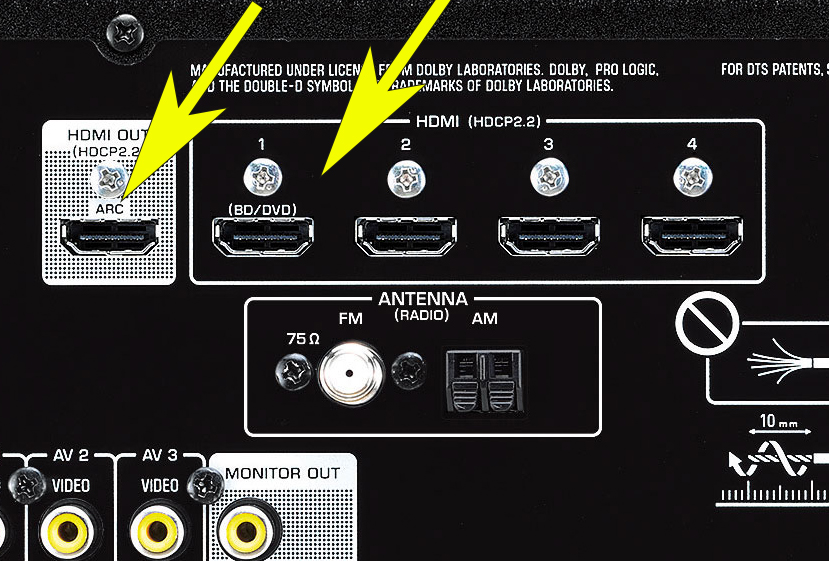

The MLC-200 utilizes the revolutionary professional digital audio platform called Dante® (short for “Digital Audio Networked Through Ethernet”) for unparalleled flexibility and sound quality. Communication to and from students (using their included wired headphones) is crystal clear, and a set of wireless headphones is provided for the instructor so that he or she can move throughout the classroom without being tethered to their teaching instrument. Also provided are all the necessary cables to connect each instrument to a central hub.

ML Touch

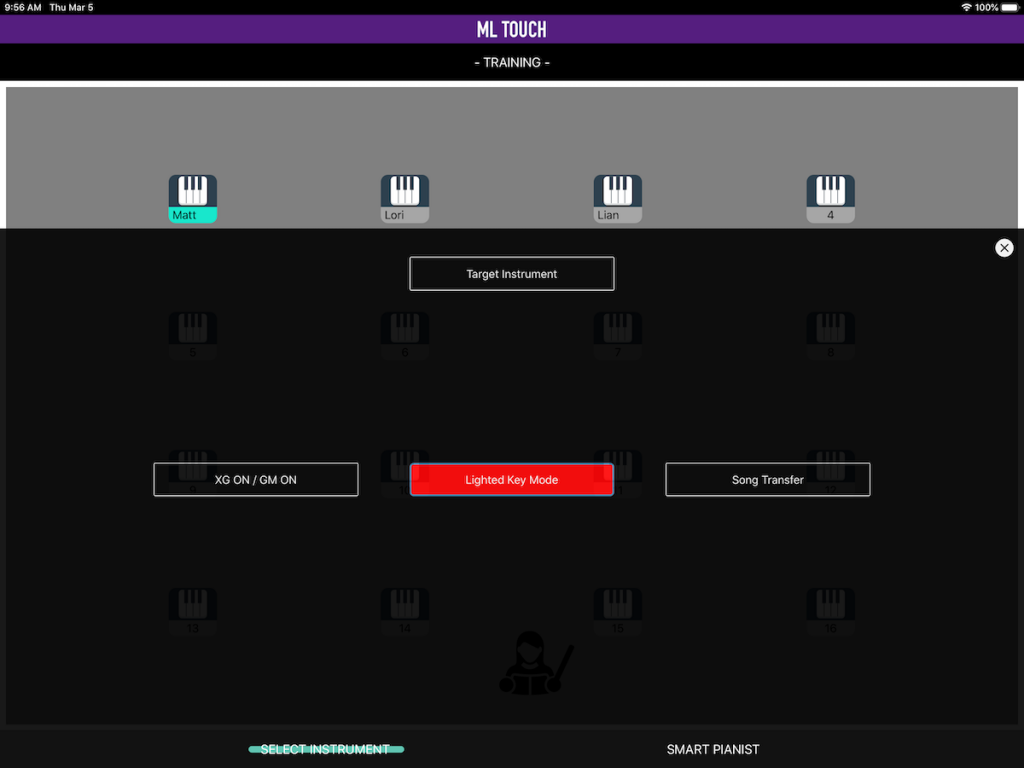

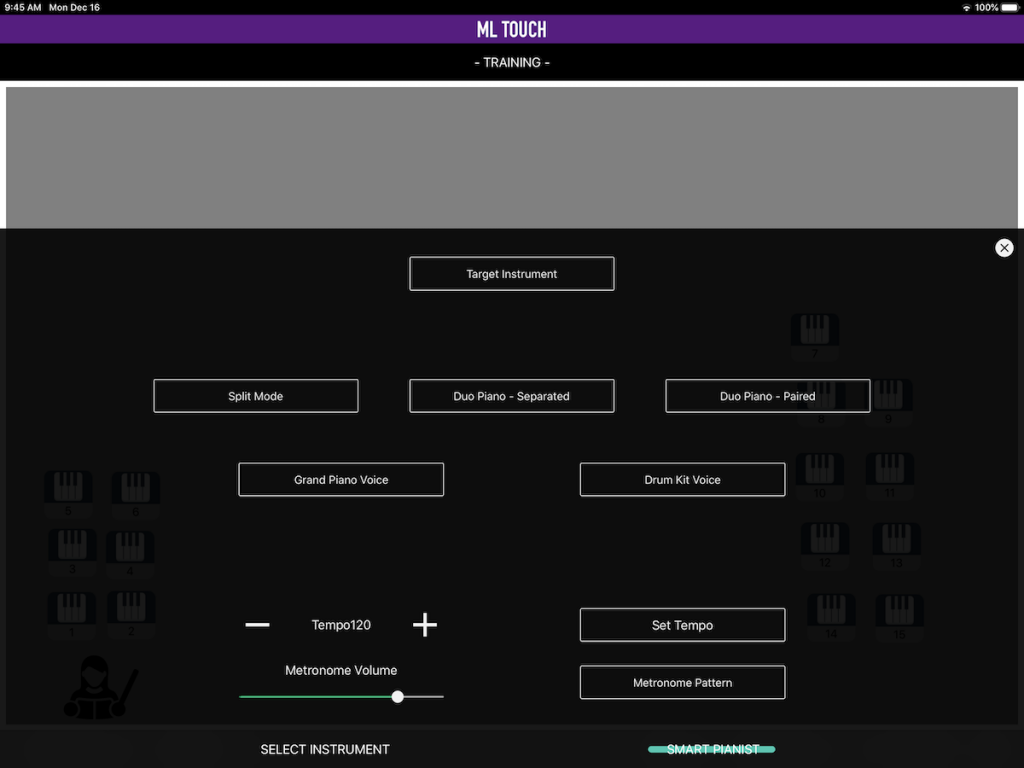

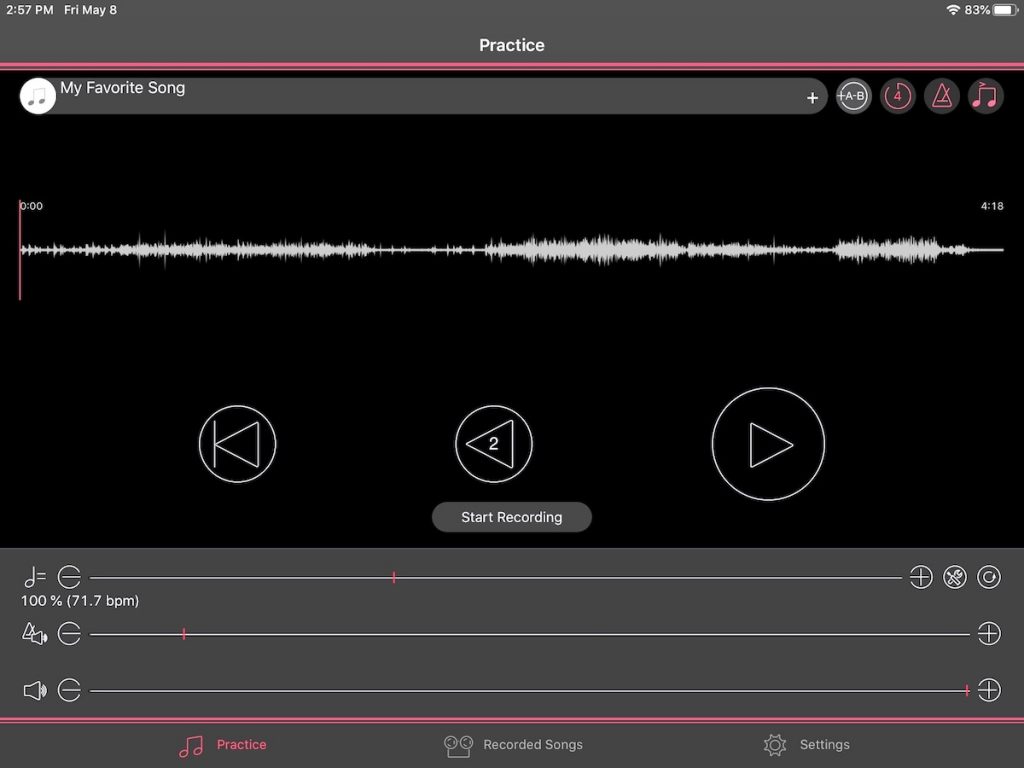

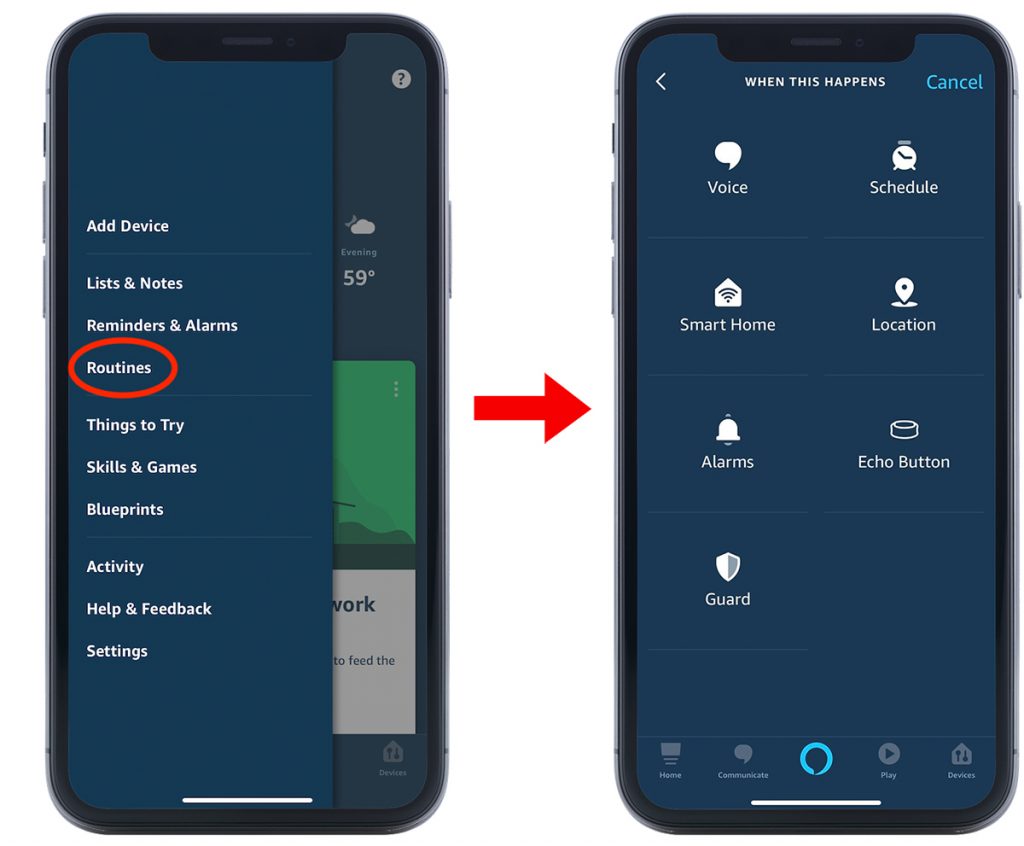

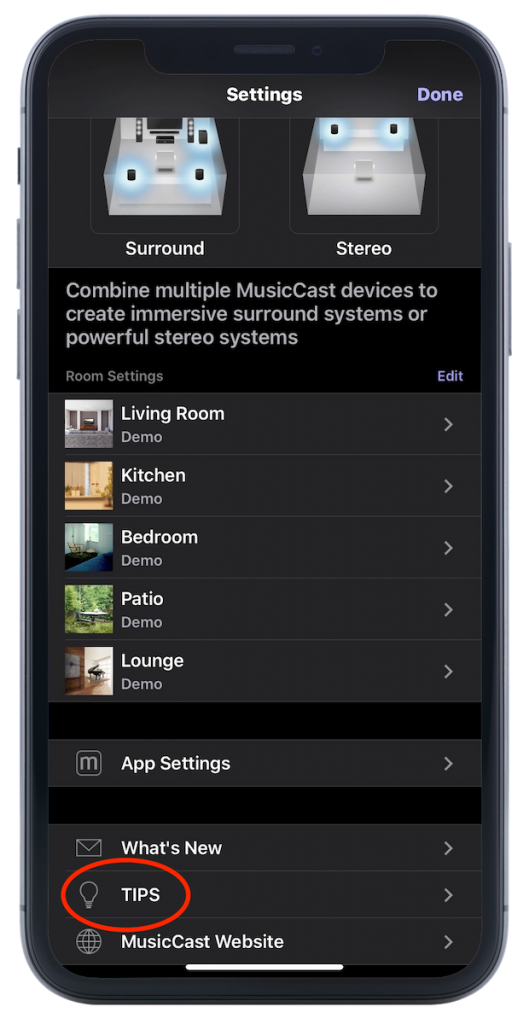

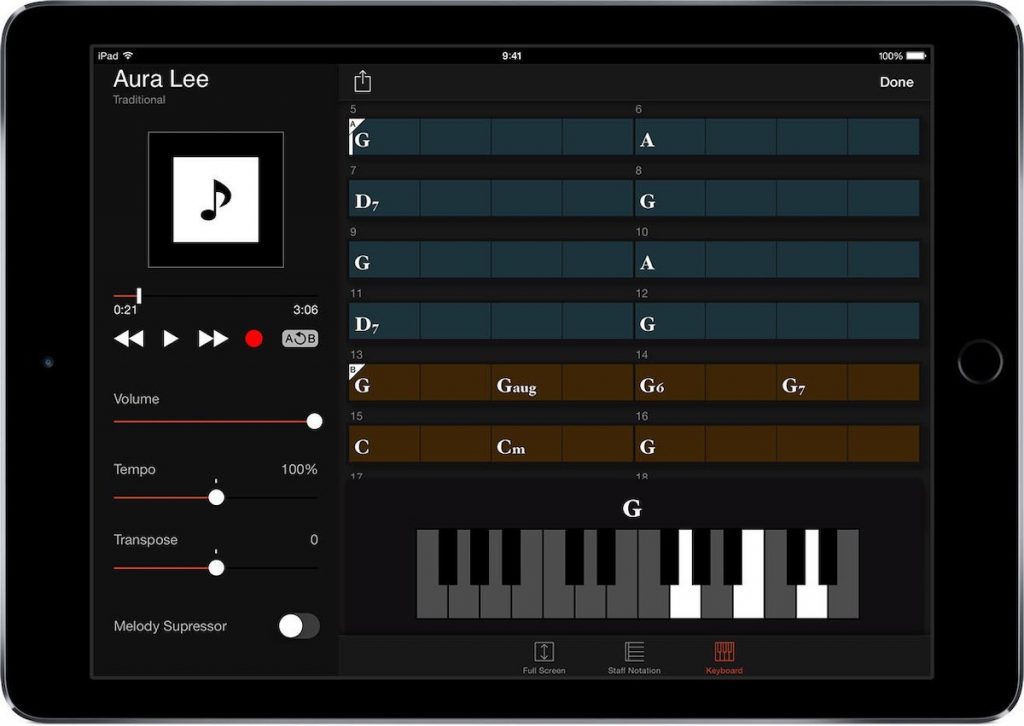

The MLC-200 is controlled from the teacher’s iPad® (not included) running a free Yamaha app called ML Touch. You can download it from the Apple® App Store for iPad ahead of time in order to experiment with most of the features without being connected to an actual lab system, or you can check out the User’s Guide here.

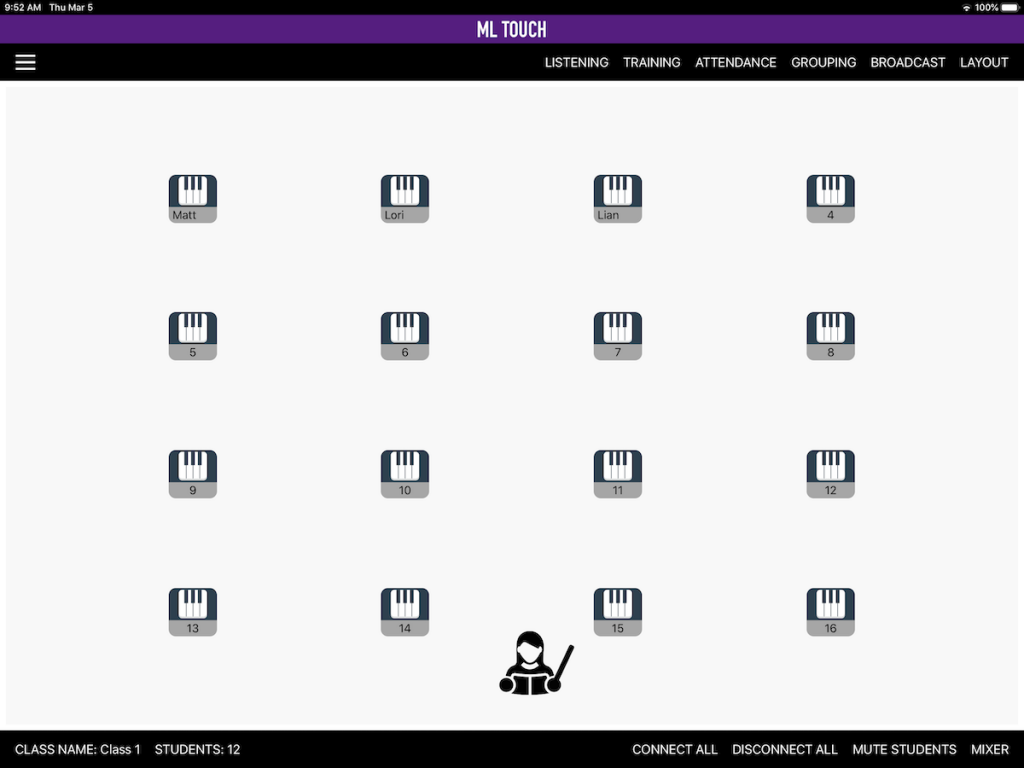

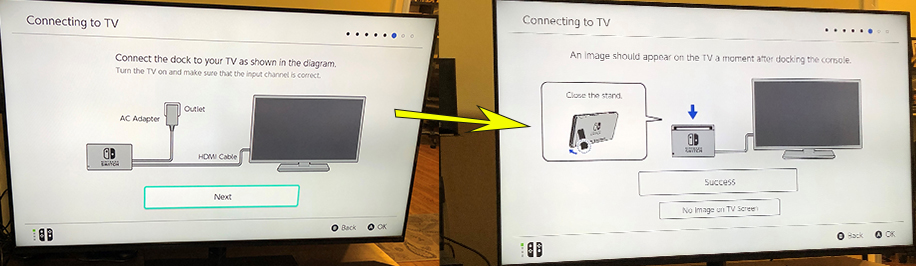

ML Touch is exceptionally easy to use — just set up your class layout, and you’re ready to go:

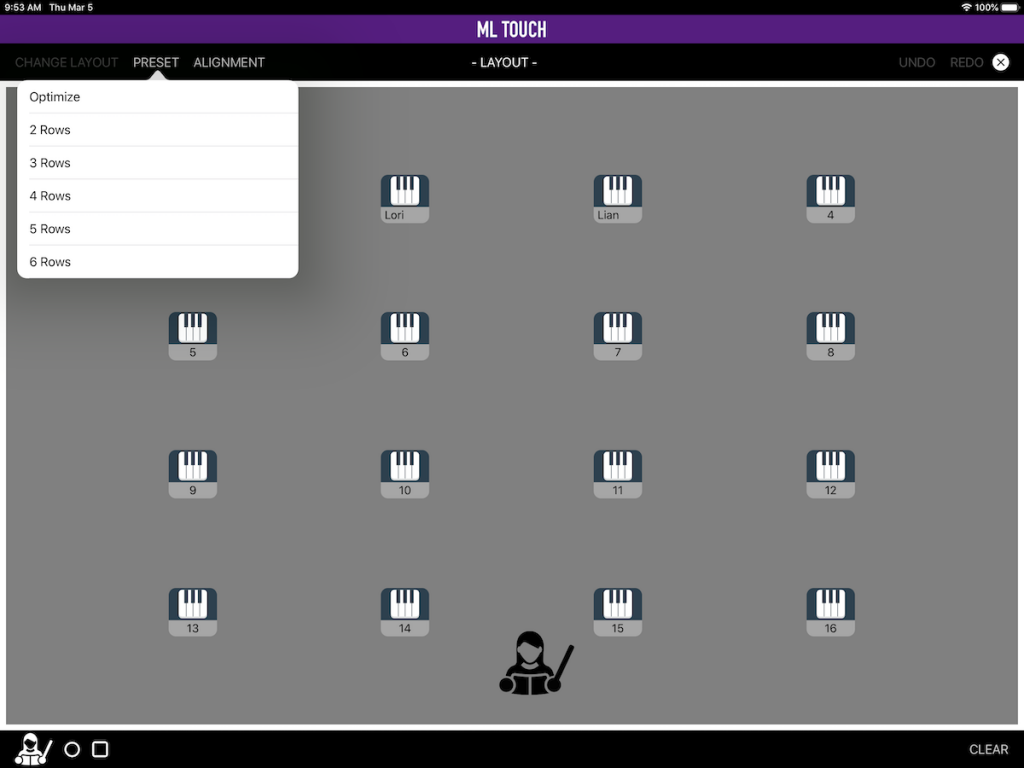

By touching LAYOUT in the upper right corner, you can move the icons around the display until your iPad looks just like your classroom. There are templates for various setups, from two to six rows, or you can completely customize the layout to match your classroom’s exact configuration.

The “Hamburger” menu in the upper left corner allows you to insert the name of each student to appear in their instrument icon. You can even take their photo and use it to accompany their name!

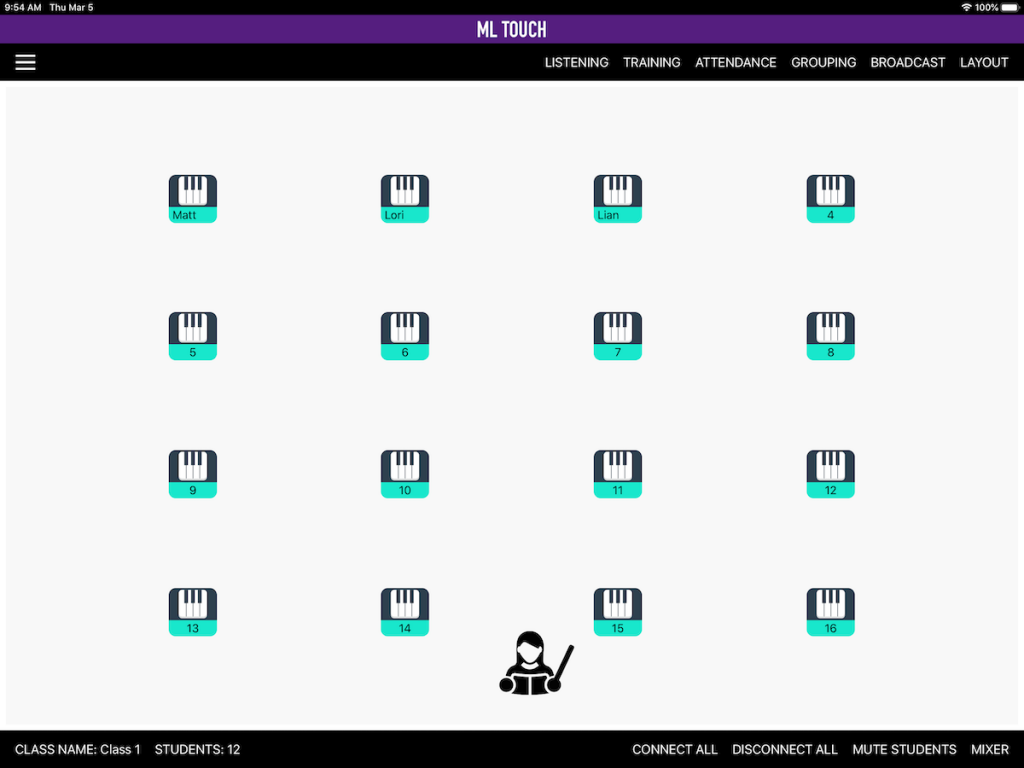

From the home page of the ML Touch app, touching CONNECT ALL highlights all student icons in green and allow you to communicate with the entire class. Each student can then hear their instrument as well as your instrument and microphone.

DISCONNECT ALL does the opposite, turning all instruments off at once. MUTE STUDENTS is particularly helpful: it instantly silences all student instruments, allowing you to instruct and demonstrate from your instrument, without students being distracted by the sound of their own instruments.

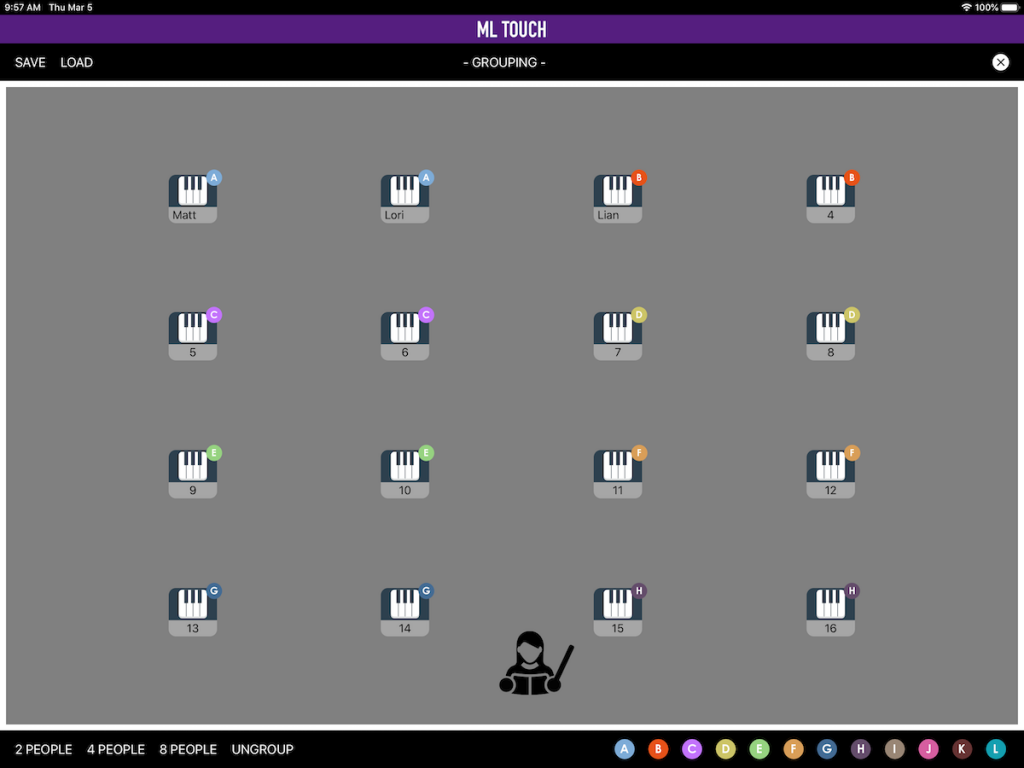

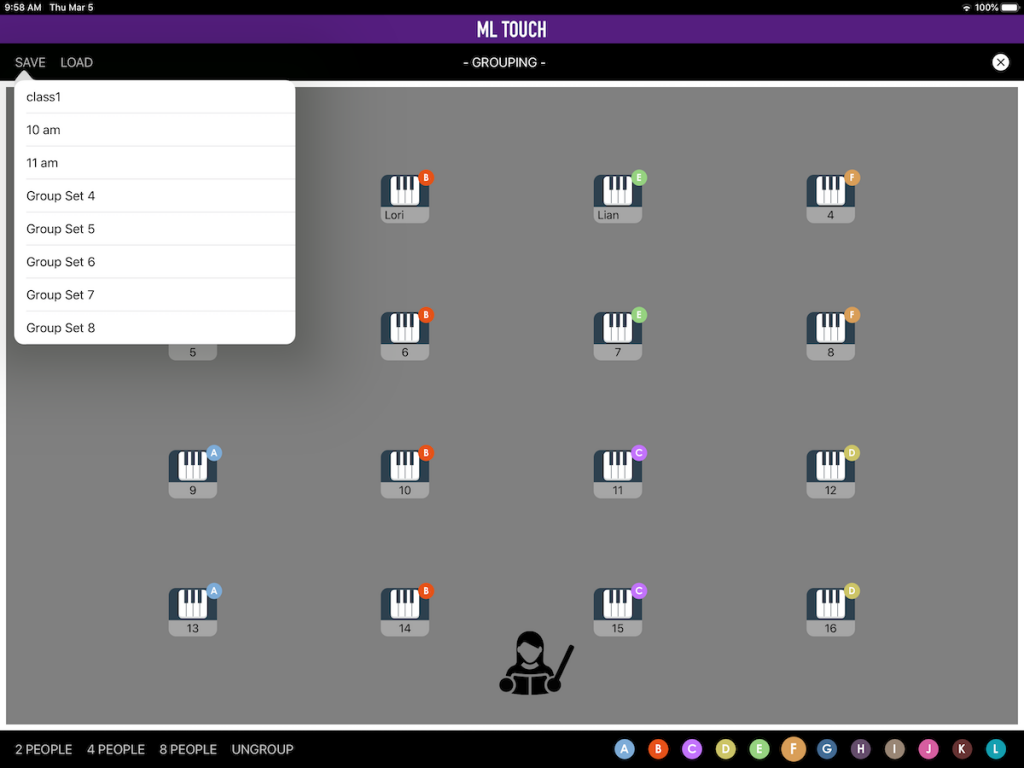

The GROUPING command in the main screen provides many helpful functions for teaching. For example, touching 2 PEOPLE in the lower left corner places students into groups of two. Four-person and eight-person groups can also be selected.

Grouping is especially helpful for duet and ensemble playing. By selecting the color-coded letters in the lower right corner, you can completely customize up to 12 different groups: Simply touch a letter and then touch the student icons you wish to be in that group. Even if students are sitting across the room from each other, they can still work together. While working in groups, students hear their instruments, as well as the instruments and microphones of the other students they are grouped with. Groups can also be saved for later use.

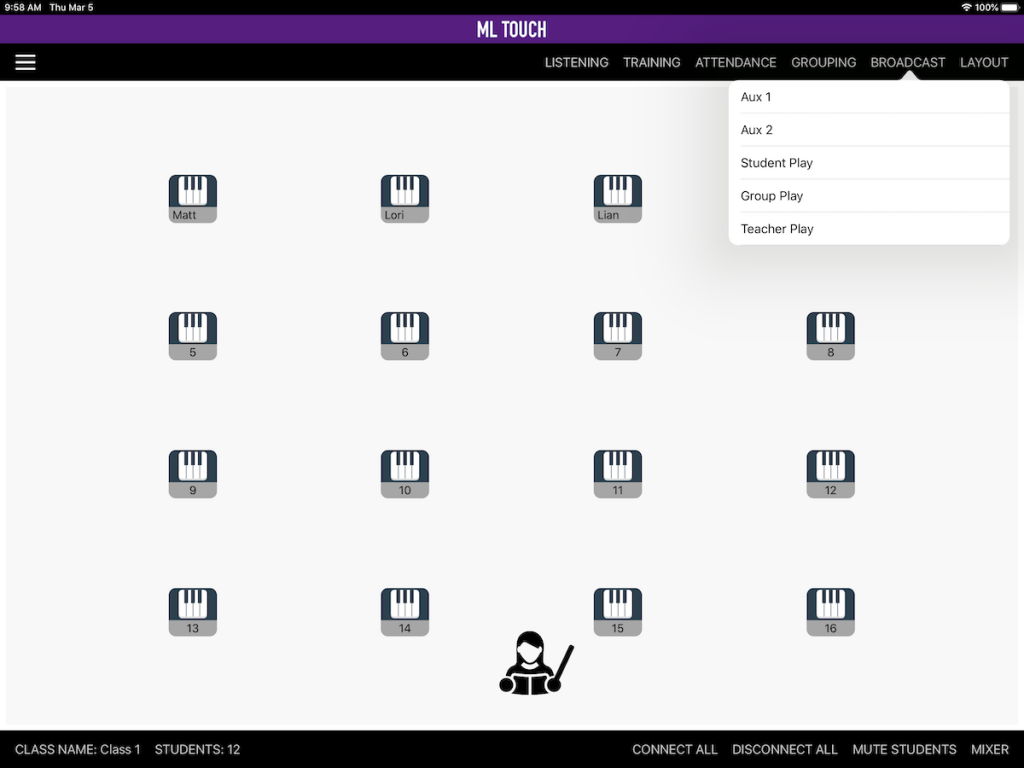

The home screen also offers a command called BROADCAST. This allows you to share the performances of an individual student, group of students, or just your instrument, so that students won’t have to constantly be unplugging their headphones to perform out loud for each other — a feature that will save lots of wear and tear on equipment!

The MLC-200 allows you to connect auxiliary devices such as a computer, music player, tablet or smartphone. The audio from these connected devices can be distributed to student headphones by selecting the AUX device you want them to hear.

Attendance can also be taken through the ML Touch app, either manually or via an Auto mode, where each student’s call light illuminates in turn at their instrument. Once they turn the light off, it will mark them as present in the app. You can later edit these records, as well as export them.

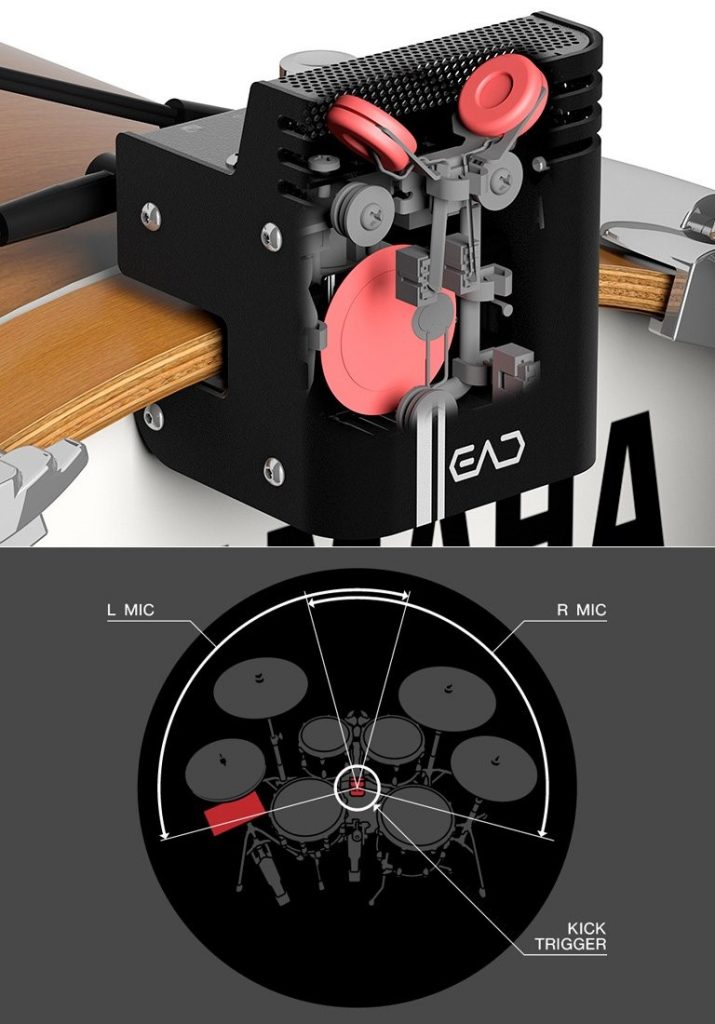

MLA-200 Interface

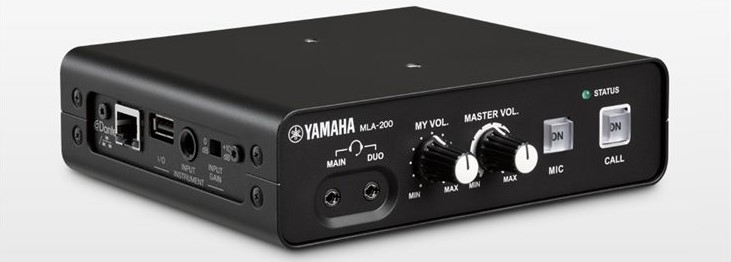

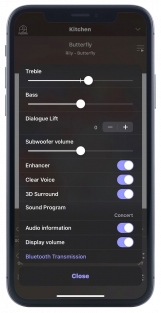

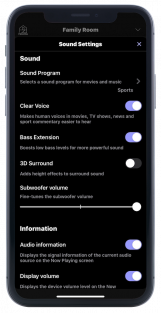

The MLC-200 system provides each student with a high-quality, durable MLA-200 interface for the connection of their instrument. From this box, the student can adjust the volume level of their instrument, as well as the teacher instrument, or that of duo or group partners. It also allows them to turn their microphone on and off, as well as call the teacher if help is needed.

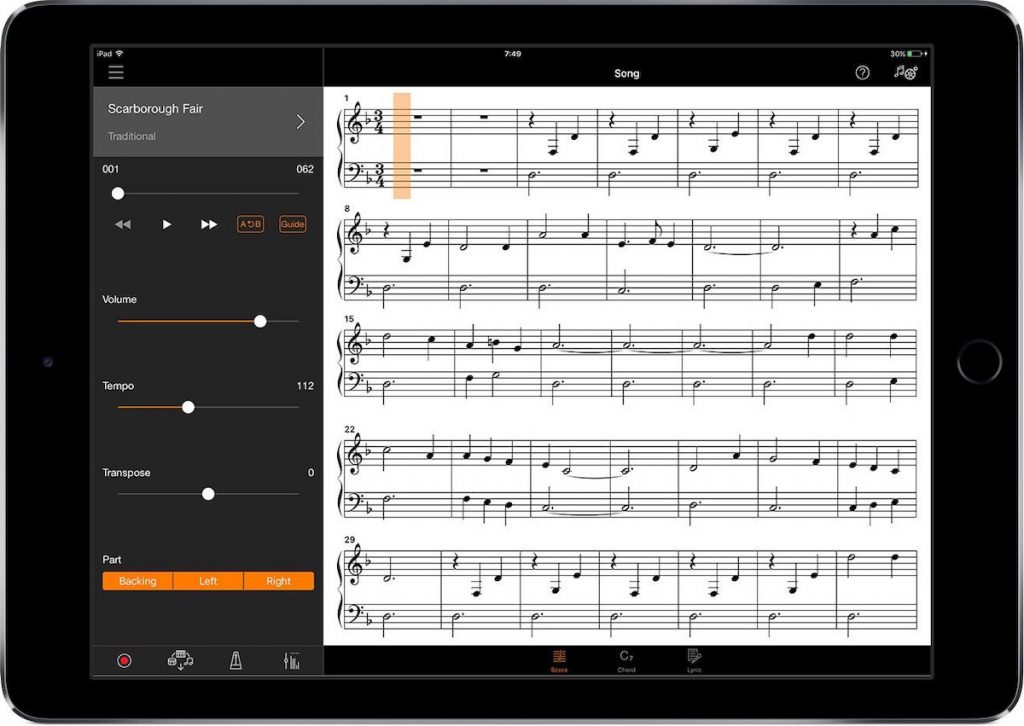

There is also a USB port on the MLA-200 that allows even greater functionality when it is used in a classroom equipped with select Yamaha CVP Clavinovas. From the instructor’s iPad, student Clavinovas can be reset back to piano sound, MIDI files can be sent to a student’s instrument, and guide lights can be sent out to the student instruments to assist with hand position during playback and keyboard drills.

Yamaha keyboards, digital pianos and Clavinovas that are compatible with the free Yamaha Smart Pianist app will also have some added features when using the USB ports on their MLA-200 interfaces. Features will vary by instrument model.

Videos

Here’s a video that provides an overview of the main MLC-200 features:

Also available for the budget-conscious classroom is the Yamaha LC4 analog lab controller, offering many of the same features as the MLC-200. With the use of an optional Wi-Fi kit, the LC4 can also be controlled by a free iPad app. Like ML Touch, this app can be run in an offline mode, so you can experiment with its features while not connected to an actual lab.

Here’s a video that shows the features of the LC4:

Both the MLC-200 and the LC4 offer instructors tremendous flexibility and can greatly enhance the group learning experience. And as a bonus, the use of systems like these allow other classrooms to be situated close by, with no sound interference coming from either direction. If you haven’t incorporated a lab controller into your teaching routine before, you may find yourself wondering how you ever got along without one!

Click here for more information about the Yamaha MLC-200.

Click here for more information about the Yamaha LC4.

Click here for more information about Dante.

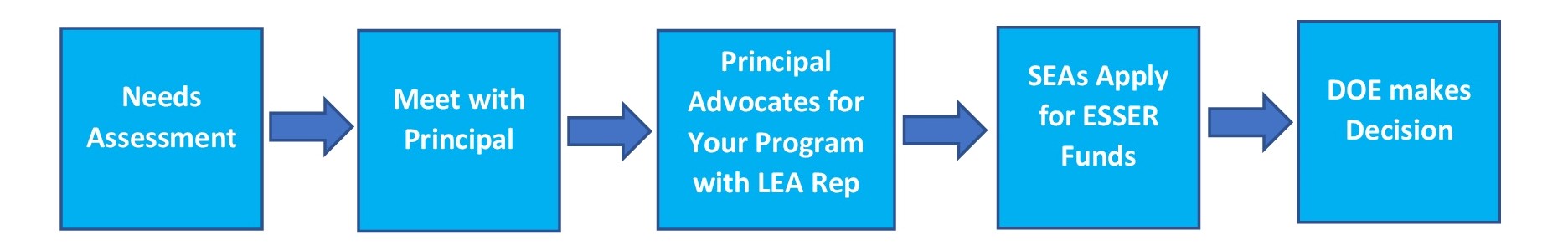

Title IV-A Funds

Title IV-A Funds Additional Resources

Additional Resources Corporate and Private Foundations and Federal Agencies that Offer Grants, Donations and Support:

Corporate and Private Foundations and Federal Agencies that Offer Grants, Donations and Support:

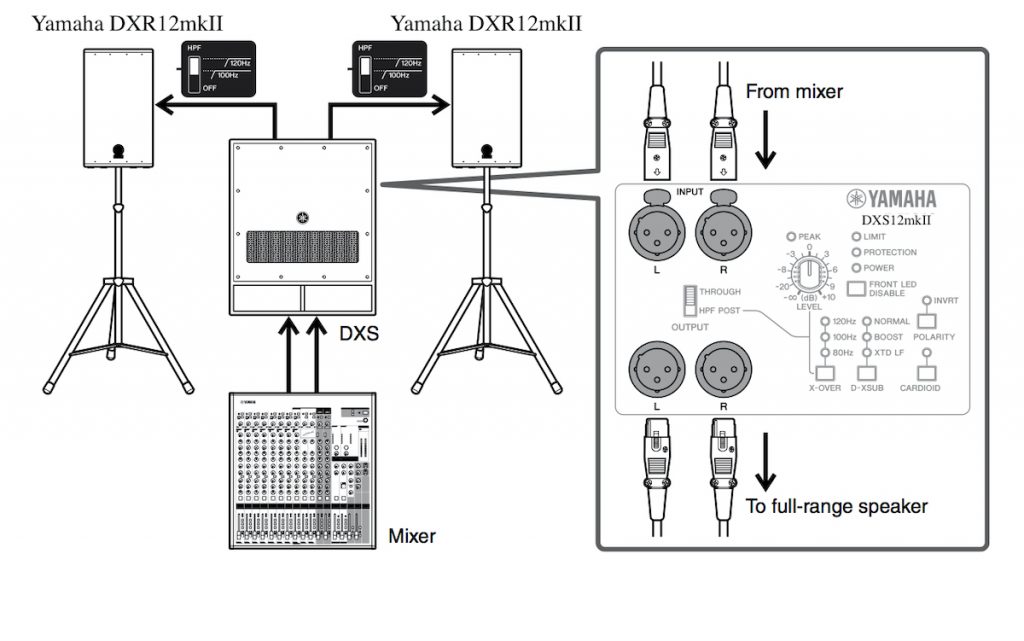

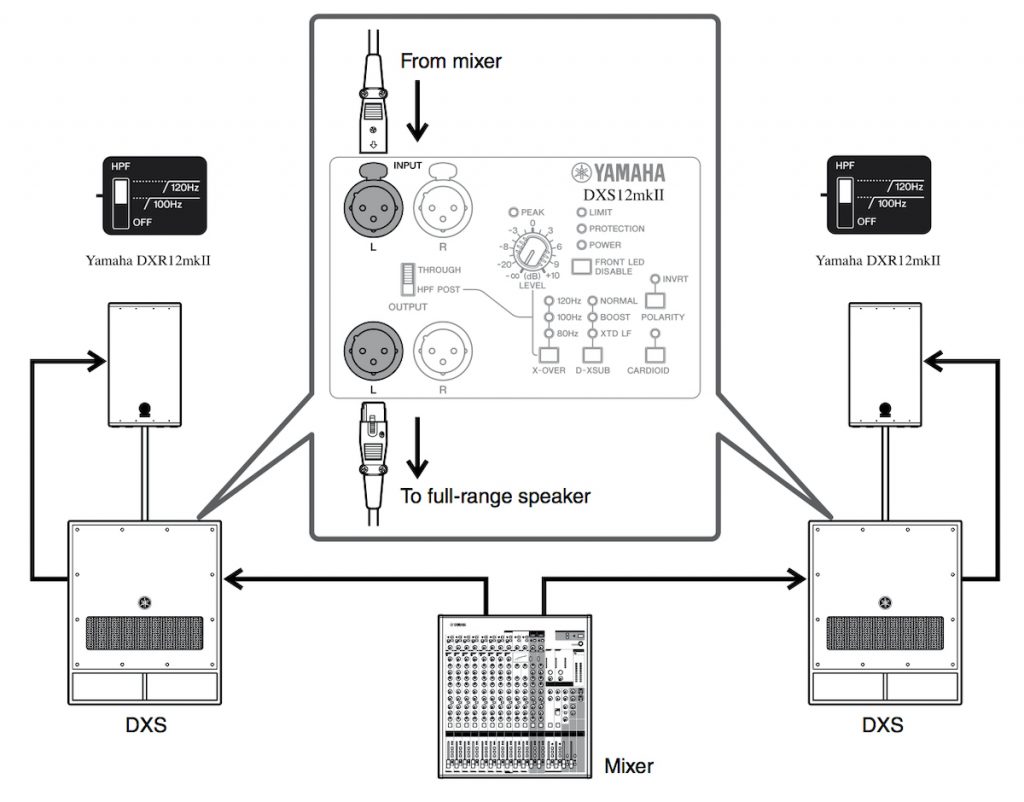

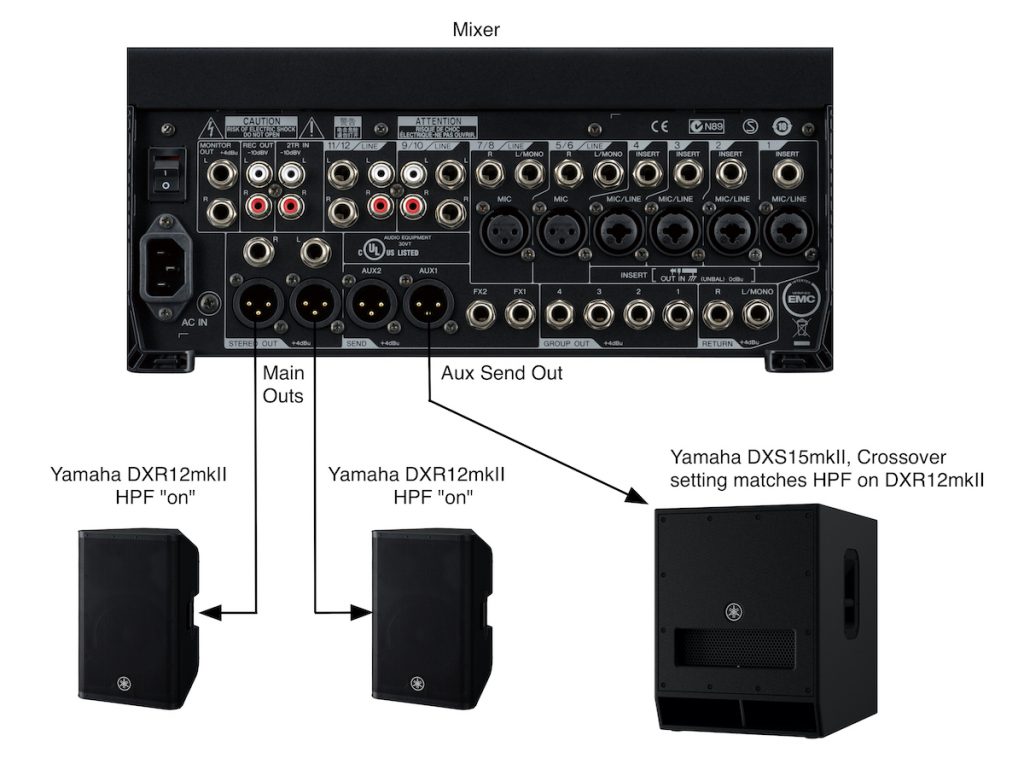

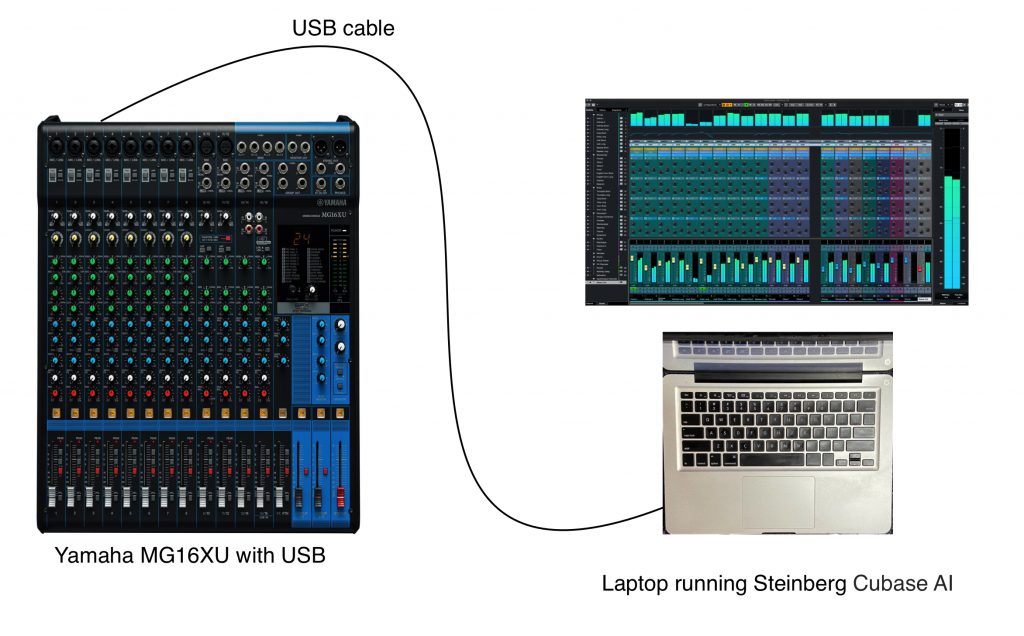

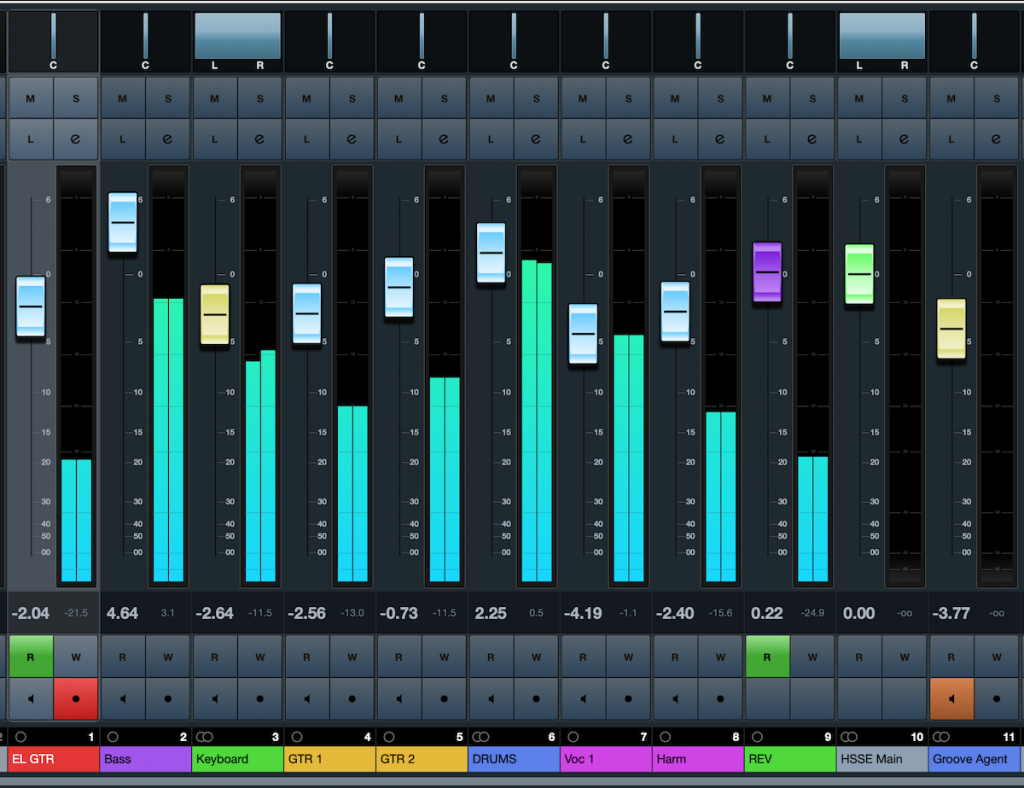

Most schools will already have a basic Public Address (PA) system in their cafeteria, gym or auditorium. In a situation where such a system is not available, small amplifiers can be used instead so that the students can hear each other. Ultimately, you will need a PA with a mixer that can blend the individual instruments into a unified stereo or mono output.

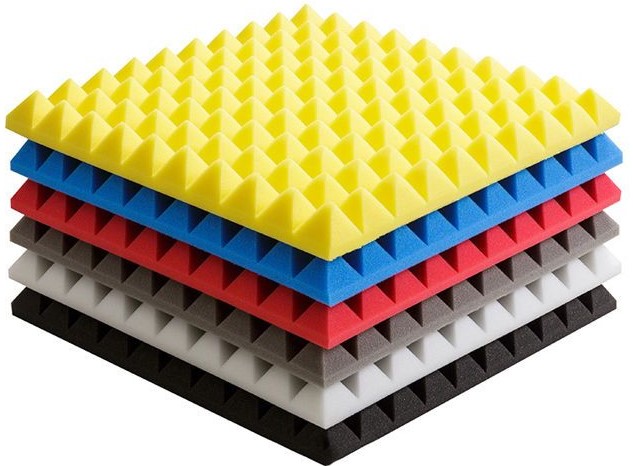

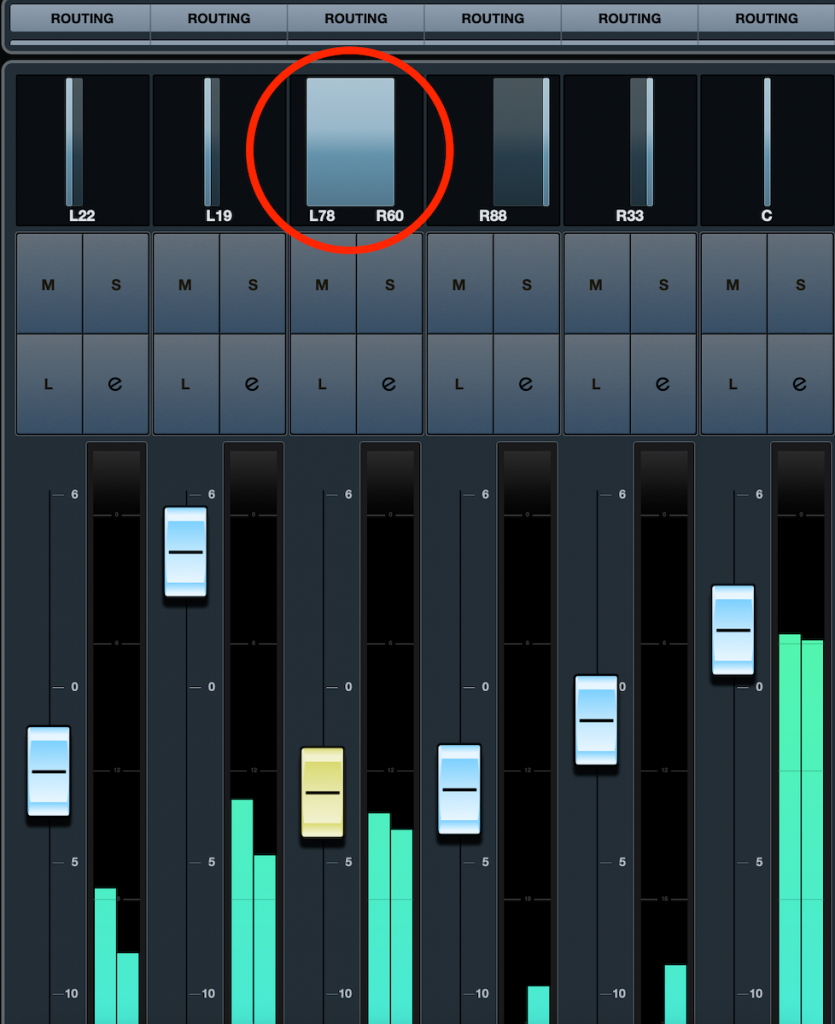

Most schools will already have a basic Public Address (PA) system in their cafeteria, gym or auditorium. In a situation where such a system is not available, small amplifiers can be used instead so that the students can hear each other. Ultimately, you will need a PA with a mixer that can blend the individual instruments into a unified stereo or mono output. You’ll also need a number of cables in lengths of 8 to 12 feet to connect the instruments to the sound system. A variety of colors works best so students know which cable is theirs. In addition, color-coding the inputs to the PA helps speed up setup time during rehearsal and live performance.

You’ll also need a number of cables in lengths of 8 to 12 feet to connect the instruments to the sound system. A variety of colors works best so students know which cable is theirs. In addition, color-coding the inputs to the PA helps speed up setup time during rehearsal and live performance.

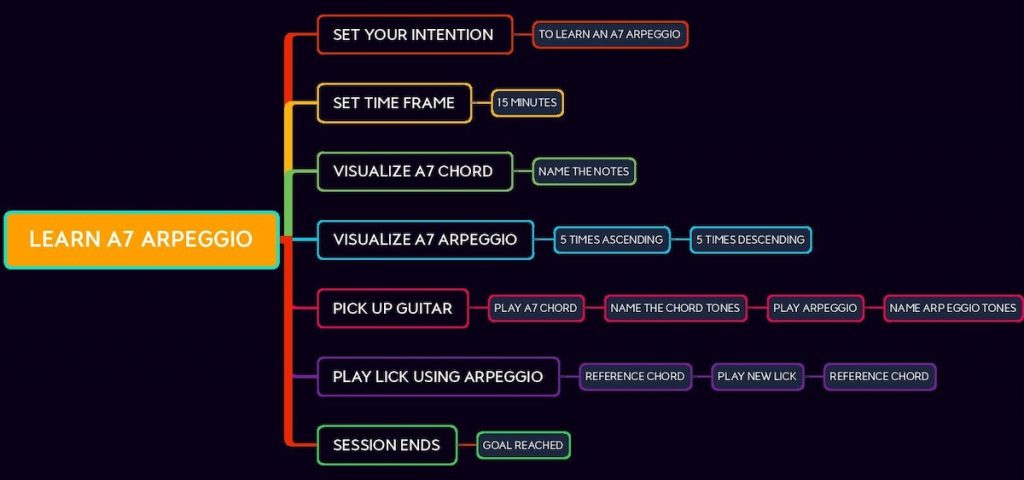

Repertoire for chamber ensembles is available for a variety of levels, making ensemble opportunities open to students with wide-ranging skills. Geiger requires students to audition, so that they work harder for spots. Typically, he writes an original piece that isolates specific skills or picks a song from an audition method book.

Repertoire for chamber ensembles is available for a variety of levels, making ensemble opportunities open to students with wide-ranging skills. Geiger requires students to audition, so that they work harder for spots. Typically, he writes an original piece that isolates specific skills or picks a song from an audition method book. Chamber ensembles are not conductor-driven, so students must be self-reliant. Radtke suggests that ensembles work best when each member is able to contribute. As opposed to having one specific leader, she appoints a new leader for each rehearsal or has students take turns cueing and leading the group in different exercises.

Chamber ensembles are not conductor-driven, so students must be self-reliant. Radtke suggests that ensembles work best when each member is able to contribute. As opposed to having one specific leader, she appoints a new leader for each rehearsal or has students take turns cueing and leading the group in different exercises.